Konservatisme tak perlu menjadi sumber kecemasan. Isu yang lebih penting bersifat sangat praktis: bagaimana negara, khususnya aparat penegak hukum, mampu menjaga ruang deliberasi yang aman.

Opinions

The secularists must learn to accommodate religion in the public sphere while the religious leaders must help balance the public role of religion with spirituality.

The government’s reason in its move to disband Hizbut Tahir Indonesia, claimed to have an ideology that contradicts Pancasila, should remind us of the “Pancasila as the sole foundation” politics of the authoritarian New Order regime.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Al Makin, a lecturer from ICRS and Ushuluddin Faculty in UIN Sunan Kalijaga, gave a fascinating presentation about his newest book Challenging Islamic Orthodoxy (Springer, 2016). He began his presentation by commenting that his research on prophethood in Indonesia may not be very new to the ICRS and CRCS community, but discussion of the polemics of prophethood is interesting as Indonesia is home for both the largest Muslim population of any country in the world and to many movements led by self-proclaimed prophets after the Prophet Muhammad. In Al Makin’s perspective, we should see this phenomenon from a different perspective, as part of the creativity of Indonesian Muslim society.

In 1993, the Ministry of Religious Affairs issued a selection of characters of what constitutes religion, include the definition of the prophet, a requirement of recognized religions. According to the Ministry of Religious Affair, prophets are those who receive revelation from God and are acknowledged by the scripture. However, following Islamic teaching, Muhamad is the seal. God no longer directly communicates with humankind. In Al Makin’s definition, prophets are those who, first, have received God’s voice and, second, establish a community and attract followers. He also reported that the Indonesian government has listed 600 banned prophets that fit these criteria. Interestingly, Indonesian prophets tend to come from “modernist” backgrounds connected to Muhammadiyah, which rejects other kinds of traditional and prophetic religious leadership, like wali and kyai.

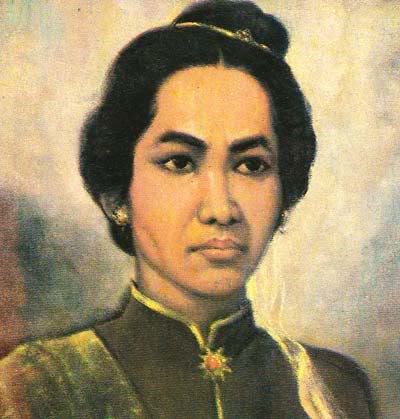

After two years of trying, Al Makin gained complete trust from one well-known prophet in Jakarta, Lia Eden, and her community of followers. The wife of a university professor, Lia Eden was famous as a flower arranger and close to members of President Suharto’s circle. She quit her career when she was visited by bright light she later identified as Habibul Huda, the archangel Gibril. After that, she became prolific in her prophecies. She found many skills that she had not had before, like healing therapy. Her circle become a movement called Salamullah, meaning “peace from God” but also referring to salam or bay leaves, used in her healing treatment.

In orthodox Islam, there are no women prophets and no prophets after the Prophet himself. The ulama declared her and her followers heretics. Lia Eden returned the criticism, accusing the ulama of being conservative and criticizing Islam as an institution, especially how the ulama council uses its political power and authority.

Al Makin closed his presentation by showing the way public has responded to Lia Eden. This movement can be considered a New Religious Movement sparks controversy because of how they attract followers. In Indonesia it is more about theology than political or economic interest like it is elsewhere. Ultimately, Al Makin argues that Indonesia’s prophets should be recognized as unstoppable—they usually become more active when in prison—but should be seen as part of the wealth of Indonesia pluralism.

Al Makin responded to a question from Mark Woodward about why Lia Eden’s community with only 30 members would become such a big problem for the government by citing Arjun Appadurai, who has argued that a small number becomes a threat to the majority in terms of its purity. It is true that she has a very small number of followers but she is also very bold and outspoken in deliver her messages constantly sending letters to many political leaders, including the ambassadors from other countries and issuing very public condemnations. Greg, another lecturer from CRCS, also asked why she is called bunda and whether she is making a gender-based critique. Al Makin answered that there have been a few other women prophets besides Lia Eden in Indonesia and that Lia Eden’s closest associates are women.

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Class Journal

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

As an American lecturer who has been working with CRCS since 2014 through Eastern Mennonite University, Virginia, he is a very well-experienced educator as he previously spent some years teaching in Japan. Moreover, his interest in following up the up-dated global issues including religious nuances, made him familiar with framing the methods of studying religion and globalization.

Global ethics is one of the topics we discussed in the class, the last material before the end of the class. Previously, we talked a lot about globalization as a phenomenon affecting religions as well as several religious responses toward globalization. Despite the supporters of globalization, many religions seem to fearfully reject it, some even proclaiming their resistance and becoming more radical.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Therefore, to foster the stabilization of the world order from war and disputes, it is necessary to rethink globalization in ways that are more ethical and friendly to the world. On the topic discussion of global ethics, we learned about attempts by world organizations like the United Nations in generating international agreements including the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Besides, other agreements such as the Cairo and Bangkok Declarations represent local voices which to some points define human rights differently.

The difference in worldviews among international actors is interesting because each organization tries to define a global value within their own relativities. Moreover, some theories think that UN Declaration on Human Right is a Western domination over other cultures without considering cultural relativities, including religions, each of which inherits different theological and structures while at the same time sharing common values like peace, humanity, equality, and justice.

World issues indeed became valuable perspective in this class. Students are meant to not only understand theories but also keep updating their knowledge on what is happening in the recent international world. While negative influences of globalization such as war, religious radicalization, and other world disputes were discussed in the class, there is also a hope for a global agreement and bright future by sharing noble values like cooperation, justice, human dignity, and peace on global scale. The existence of world organizations and religious representatives in fostering global ethics proves the progress made towards creating world peace. The duty of students, in this case, is to contribute academically to spreading such values without neglecting the variety of cultural and religious perspectives.

*The writer is CRCS’s student of the 2016 batch.

Aksi Super Damai 212 patut diapresiasi sebagai bukti kemajuan dan kedewasaan umat Islam Indonesia dalam mengekspresikan aspirasi politiknya. Kesejukan yang hadir dalam aksi ini sudah seharusnya diapresiasi.

Namun demikian, bagi peserta aksi, tujuan mereka bukan sekadar membuktikan bahwa Aksi Bela Islam adalah gerakan damai. Ratusan ribu atau bahkan lebih dari sejuta orang bersusah payah mendatangi Jakarta dalam aksi 212. Sebagian bahkan rela jalan kaki berhari-hari demi “membela Islam”, dengan tuntutan memenjarakan Ahok. Menariknya, meskipun Ahok tidak ditahan, para peserta aksi 212 tampak pulang dengan perasaan menang.

Sampai esai ini ditulis, perayaan kemenangan masih berlanjut. Linimasa masih dibanjiri konten dan unggahan yang menunjukkan kedahsyatan momen setengah hari di bawah Monas itu. Sebagian bahkan menawarkan cenderamata dan kaos untuk mengenang momen kemenangan.

Lantas pertanyaannya: apa yang sebenarnya telah dimenangkan?

Perang Posisi, Bukan Perang Manuver

Bagi banyak orang, partisipasi dalam aksi 212 bisa menjadi bagian dari momen langka yang tidak terlupakan. Berada di tengah lautan manusia untuk “membela Islam” merupakan kepuasan spiritual. Aksi yang begitu besar, yang dilakukan dengan tertib dan tanpa menyisakan sampah, adalah sebuah kemenangan dalam melawan wacana atau tuduhan tentang ancaman kekerasan dan makar.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

In a world so full of complexity, how does intimacy work? To Dian Arymami, it is very significant and important to revisit the understanding of intimacy because she observes the transformation of intimacy is connected to the transformation of society. The practice, the understanding of intimacy have been reconstructed from time to time. Usually people would think about intimacy as an act of loving, but up to now there are many cases show that intimacy could be something out of love, outside of committed relationship and, to be more precise, outside of marriage. Moreover personal needs and desires are also part of our religiosity. Religiosity and intimacy are not totally opposed to each other.

Dian Arymami’s ongoing research on new kinds of intimacy in the phenomenon of extradyadic or non-monogamous relationships that have quickly become widespread in urban areas of Indonesia is not advocacy on behalf of a group of people but she insists that she is studying the voices of the voiceless. Their emergence can be seen on a practical level as a rebellion against the structure and social fabric of Indonesian society but at the same time as part of an ongoing shift of ideological values and norms. Those who practice extradyadic relationships are a voice that could not be heard by the society because people would always claim that the problem is in person not society. We must think about this kind of intimacy as a social phenomenon and not a personal disease or failing.

Therefore, Dian came up with the signs of embodied practice of intimacy in the schizophrenic society. It related to something that material not representation. It is social not familial and she continue by saying that it multiplicity not personal. Many things transform relationships. According to the cases that Dian come up with, the social media is one of the biggest influence in transforming relationship in society. The discourse about intimacy embodied in the way people perceive things like divorce, sexuality, dating style, poly-amor trend and many others to follow. To define schizophrenic society, she refers to the theory of Gilles Delueze and Felix Guattari about the process of schizophrenia. Unlike Freud’s understanding about paranoia, the schizophrenic term in Delueze shows a condition of an experienced of being isolated, disconnected which fail to link up with a coherent sequence. She than continues that no one is born schizophrenic. Instead, schizophrenia is a process of being. In the schizophrenic society, everyone experiences diverse meanings in relation to other objects, and, in the other times or places, no meaning at all. In other words, meanings are based on the schizophrenic’s object experiences, but it is society itself that must be understood as schizophrenic.

By highlighting her respondents’ experiences, Dian shows that there are many consequences of the practice of intimacy or intimate relationships in (as) the schizophrenic society including “value crash,” double life, “time and place crash” and many others. In extradyadic relationship people become a substitution for something that they cannot fill.

In the question and answer session, there were many fascinating questions about this topic. Zoyer, a researcher concerned with on-line dating in Yogyakarta, offered the idea that the complexity of intimate relationships in urban areas in Indonesia is affected by the cultural expectation that young people marry by certain ages. That is why people are trying to free themselves by “jumping into the extraordinary.” The other question brings us to a reflection about what are the practitioners of these extradyadic relationships are becoming in society. Dian answered by changing the question: instead of questioning a person’s behavior, we must question society. Dian closed her remarkable presentation by stating that the idea of love is not exclusive and absolute.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Quoting the great French novelist Victor Hugo’s remark that “Life is a compilation of stories written by God” Inandiak highlighted how meaning is found in stories which come before larger systems like religion. In her book and her talk, she told stories from her experiences with the victims of natural disasters in two communities, one, Kinahrejo, in the North and one, Bebekan,in the South. Inandiak explained that the process of recovery after a natural disaster is a process with and within the nature. It is about the reconciliation between human communities and nature. In natural disasters people mostly lose their belongings such houses, money, clothes and domesticated animals, but, she said, the most important thing is not to lose their identity. Houses can be rebuilt, but once people lose identity they don’t know how to rebuild anything else. Inandiak spoke about the disaster as a conversation between the North and the South. This is also a kind of stories that helps people deal with their situation, by accepting that disaster are part of natural cycles.

Inandiak also spoke about rituals. First there were the rituals enacted by Mbah Maridjan and Ibu Pojo, the shamaness who was his unacknowledged partner, to connect human communities and nature. The offering ritual they made to Merapi included three important layers that describes their own identities: ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam especially Sufism. Despite all the issues that Mbah Marijan and Ibu Pojo faced before they died in the 2010 eruption, they insisted what they were doing is an act of communicating with the nature that was their home. Second, in order to overcome the difficulties after a disaster, stories and ritual mean a lot for reestablishing the victims’ identity. By doing rituals like dancing or singing, they connect to the wishes that become true. The wishes that they made bring such a different in their perspectives in continuing life. Through ritual people want to get connected with nature and Inandiak told how she helped these villages rebuild their identities.

In the question and answer session, we were moved by many fascinating question about the relation of nature and person. One of them is how the three layers in Javanese ritual—reverence for ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam, particularly Sufism—deal with the interference of world religion. Inandiak responded that there must be many changes brings by the world religion, especially in Kinahrejo, where Mbah Maridjan faced pressure from fundamentalists. The way villagers perceive myth changes from time to time. Their Muslim-Javanese identity is something they need to maintain in negotiation. In answering the issues about participants in the rituals wearing hijab, Inandiak argued that these layers should be clearer. They are not rooted in one story. But to maintain the customs is also important.

Inandiak closed her presentation with a remarkable message that disasters come from the interaction of people and nature but no one should feel guilty or think that any disaster is the result of sin or human mistakes. The most important things are not to give up and to work to rebuild identity.

Zainal Abidin Bagir | CRCS UGM | Opini

Tak sedikit tokoh, pejabat, politisi bahkan polisi yang memuji gelombang aksi protes terhadap ucapan Gubernur DKI Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) yang kontroversial itu. Pujian-pujian itu beralasan, karena meskipun kelompok yang memobilisasi atau mendukung demo tampaknya berasal dari spektrum yang amat luas, mulai dari yang sangat moderat hingga yang disebut garis keras, tuntutan akhir mereka sama, yaitu menuntut agar Ahok diproses di jalur hukum, secara adil dan berkeadilan.

Supremasi hukum demi tegaknya keadilan tentu adalah jalan beradab, demokratis dan moderat. Tapi benarkah demikian? Saya khawatir, imajinasi tentang keadaban dan sikap moderat seperti ini terlalu cetek. Tentu tidak keliru, tapi tidak cukup. Penyelesaian masalah melalui jalur hukum harus dipuji, jika alternatifnya adalah respon kekerasan. Namun, khususnya dalam kasus “penistaan agama”, ada banyak alasan untuk meragukan bahwa seruan itu adalah jalan terbaik untuk memecahkan masalah, dan mungkin justru tak menjanjikan keadilan.

Sebab utamanya adalah bahwa peristiwa ini (ucapan Ahok dan pembingkaian atas peristiwa itu sebagai “penistaan agama”), jika masuk pengadilan, kemungkinan besar merujuk merujuk pada Pasal 156A KUHP, yang tidak memiliki karir gemilang dalam sejarah Indonesia. Ini adalah bagian dari pasal-pasal karet “kejahatan terhadap ketertiban umum” dalam KUHP. Pasal yang ditambahkan pada tahun 1969 atas perintah UU 1/PNPS/1965 ini memiliki nilai politis yang amat kuat. Target awalnya adalah untuk membatasi aliran-aliran kebatinan/kepercayaan yang terutama bersaing dengan kekuatan politik Islam pada tahun 1950 dan 1960an.

Setelah tahun 1998, target itu bergeser. Target lama tetap ada, meskipun bukan mengenai aliran-aliran kebatinan lama, tapi gerakan-gerakan baru seperti Salamullah yang dipimpin Lia Eden, atau Millah Abraham. Tak ada isu politik penting dalam mengejar kelompok-kelompok itu, namun alasan utamanya adalah “pemurnian” Islam (dan mungkin alasan soisal-ekonomi-politik lain). Selain itu, tujuan baru penggunaan pasal ini adalah sebagai upaya peminggiran intraagama, yaitu kelompok-kelompok dalam komunitas Muslim sendiri, seperti Ahmadiyah dan Syiah, yang sebetulnya sudah eksis di Indonesia sejak jauh sebelumnya. Dalam Kristen, ada beberapa kasus serupa. Pasal penodaan agama jarang digunakan sebagai ekspresi perselisihan antaragama, kecuali dalam beberapa kasus.

Melihat rentang wilayah penggunaan pasal KUHP itu, kita bisa segera mencurigai efektifitasnya. Bagaimana mungkin keyakinan (misalnya bahwa Nabi Muhammad adalah Rasul terakhir dalam Islam) dijaga dengan pasal yang sama yang memenjarakan orang selama 5 bulan karena memprotes speaker masjid yang terlalu keras (seperti di Lombok pada 2010; seorang perempuan Kristen yang mengomentari sesajen Hindu (seperti di Bali pada 2013); atau seorang “Presiden” Negara Islam Indonesia yang mengubah arah kiblat dan syahadat Islam, namun kemudian pada 2012 hakim memberi hukuman setahun, untuk dirawat di Rumah Sakit Jiwa. Itu hanyalah beberapa contoh yang bisa diperbanyak dengan mudah.

Selain rentang implementasi yang demikian luas, persoalan lain adalah amat kaburnya standar pembuktian kasus-kasus semacam itu. Kasus-kasus yang diadili dengan Pasal 156A tersebut biasanya menggunakan cara pembuktian serampangan, dengan pemilihan saksi ahli yang tak jelas standarnya pula (dalam satu kasus pada tahun 2012, seorang yang diajukan sebagai saksi ahli agama bahkan tidak lulus sekolah). Penistaan atau penodaan bukan sekadar pernyataan yang berbeda, tapi—seperti dinyatakan Pasal 156A itu—mesti bersifat permusuhan, penyalahgunaan atau penodaan, bahkan mesti ada maksud supaya orang tidak menganut agama apapun. Apakah Ahok, yang membutuhkan suara mayoritas Muslim Jakarta, berpikir untuk memusuhi mereka?

Selain itu, apakah ia dianggap menghina Islam, atau ulama? Yang dikritiknya adalah Muslim yang disebutnya membohongi pemilih DKI dengan menggunakan ayat 51 surat Al-Maidah. Apakah muslim seperti itu identik dengan Islam, sementara banyak ulama dan terjemahan Al-Qur’an memberikan tafsir berbeda?

Dalam kenyataannya, jika kasus ini masuk ke pengadilan, seperti dapat dilihat dalam banyak kasus, pertanyaan-pertanyaan tentang standar pembuktian kerap diabaikan. Yang menjadi pertimbangan yang tak kalah penting adalah “ketertiban umum” (yang menjadi judul Bab KUHP yang mengandung pasal tersebut). Persoalannya, ancaman terhadap “ketidaktertiban umum” itu lebih sering dipicu oleh pemrotes yang merasa tersinggung, dan bukan pelaku itu sendiri. Karena itulah, demonstrasi besar jilid satu dan dua pada 4 November nanti—dan bukan ucapan Ahok itu sendiri—menjadi penting sebagai dasar untuk menggelar pengadilan atas Ahok.

Pemurnian sebagai politik

Penting dilihat bahwa dalam kenyataannya, Pasal 156A dipakai hanya selama sekitar 10 kali sejak tahun 1965 hingga 2000, dan tiba-tiba dalam 15 tahun terakhir demikian populer, telah digunakan sekitar 50 kali! Apakah setelah Reformasi ada makin banyak para penoda agama atau orang-orang yang sesat? Atau ada penjelasan lain dengan melihat transisi politik pada 1998?

Seperti halnya pasal-pasal kriminal serupa di banyak negara lain tentang “penodaan”, “penistaan”, atau “blasphemy”, upaya seperti ini biasanya memang menggabungkan dua tujuan sekaligus: tujuan penjagaan “kemurnian agama” (tentu dalam versi kelompok yang memiliki kuasa untuk mendiktekannya) dan tujuan politik. Pasal ini menjadi instrumen efektif untuk menjalankan politik “pemurnian” agama, yaitu penegasan kuasa politik suatu kelompok keagamaan.

Pada tahun 2010, UU ini dan Pasal 156A diajukan ke Mahkamah Konstitusi. Benar MK mempertahankan pasal ini, namun perlu dilihat juga catatan panjang yang diberikan para hakim MK tentang kelemahan-kelemahannya, dan saran agar pasal ini direvisi supaya tidak diskriminatif serta mendukung pluralisme Indonesia. Bahwa ada unsur politik, bukan semata-mata pidana, dalam pasal ini, tampak dalam pertimbangan MK yang panjang, hingga mengelaborasi persoalan filosofis mengenai hubungan agama dan negara, dan sejarah Indonesia sebagai negara berketuhanan.

Bagaimana mengatasi Ahok: Imajinasi yang lebih kaya

Maka kita bisa bertanya, apa sebetulnya tujuan dari keinginan besar untuk mengadili Ahok sebagai penista agama? Soalnya mungkin bukan tentang umat Islam yang sudah seharusnya tersinggung atas upaya penistaan agamanya. Pertama, ketersinggungan itu mungkin dirasakan setelah pernyataan Ahok itu dibingkai orang dan kelompok tertentu, yang lalu memobilisasi massa. (Sekali lagi, ini mirip dengan kasus “penodaan” lain, seperti kasus kartun Denmark.)

Selain itu, jika tak ada alasan politik praktis menjelang pilgub DKI atau yang lain, tapi ini soal menjaga kemurnian agama, benarkah kita mau menggantungkan kemuliaan agama pada satu pasal karet yang sama yang telah digunakan untuk mengadili orang dengan gangguan kejiwaan, pencabut speaker masjid, seorang ibu rumah tangga yang mengomentari sesajen Hindu, atau banyak kasus-kasus lainnya?

Baca lagi –> https://islamindonesia.id/

_________

Penulis adalah seorang Dosen Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies – Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta.

Azis Anwar Fachrudin | CRCS UGM | Opinion

Despite the fact that Jakarta Governor Basuki “Ahok” Thahaja Purnama has apologized for statements made regarding the Quranic verse Al-Maidah 51, some Islamic groups are saying that an apology is not enough. Protestors demanded that Ahok be criminalized in a rally last week in Jakarta.

Deputy secretary-general of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) said on a TV show that religious defamation must be punished by “death, crucifixion or at least hand amputation and expulsion”. Even though he did not urge the state to adopt such a policy, but rather called on the processing of the case in accordance to the law on religious defamation, his remarks give the impression that Islamic law is that harsh.

The Quranic verses quoted by the MUI deputy secretary-general are known as the hirabah verses. Hirabah, which literally means “warfare”, and the verses were basically applied under the principles of Islamic jurisprudence to crimes such as highway robbery, piracy, unlawful rebellion and sedition. The verses were the same verses used by the Islamic state (IS) group to justify its crucifying of those waging war against IS.

Therefore, the attribution for those punishments for alleged religious defamation is dangerous.

What is more saddening is that Islamic groups are pushing for Ahok to be criminalized when he had no intention of insulting Islam or the Quran. The groups are insisting that the literal out-of-context interpretation of al-Maidah:51 is the only correct one. They take for granted that the verse literally prohibits non-Muslims from being a “leader” in a Muslim country.

The word auliya is not translated as “leader” in most contemporary translations as well as tafsir, the consequence of that translation is dangerous: non-Muslim ministers, regents, even bosses in companies where Muslims work are also leaders, aren’t they? Must they be dismissed from their positions just because of the verse?

The verse will only make sense if understood in its context, that is, in a situation of war, such as when the Jews were said to have betrayed the Muslims by violating the social contract made between the two to defend Medina together when the city-state was under attack; hence the later prohibition to make the Jews “allies” (the closest meaning to the word“auliya”).

Read more http://www.thejakartapost.com/

________________________

The writer is a graduate student at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS) at Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta.

Suhadi | CRCS | Opinion

As i observe, the discipline of religious studies that is growing in Southeast Asian countries nowadays has several characteristics that make it different from how religion has been studied until now. First, it goes beyond theological approaches and stresses religious practice in relation to society, politics and culture. Second, it is part of the response to social and political issues outside the academy, such as inter-religious conflict, the absence of the freedom of religion, gender inequality, social injustice, etc. For these reasons, I am interested to explore the emergence of this discipline in the context of Southeast Asia.

As i observe, the discipline of religious studies that is growing in Southeast Asian countries nowadays has several characteristics that make it different from how religion has been studied until now. First, it goes beyond theological approaches and stresses religious practice in relation to society, politics and culture. Second, it is part of the response to social and political issues outside the academy, such as inter-religious conflict, the absence of the freedom of religion, gender inequality, social injustice, etc. For these reasons, I am interested to explore the emergence of this discipline in the context of Southeast Asia.

I presented these ideas about the emerging discipline of religious studies in the Southeast Asian context at the research seminar entitled “Making Southeast Asia and Beyond” at the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand, in January 2016.

Southeast Asia is home to communities of believers in the world’s major religions and traditions, in addition to various indigenous religions and other smaller world religions. Major groups by percentage of the Southeast Asian population are Muslims (36.77%), Buddhist (26.78%), Christians (22.06 %), and ethno-religionists (4.61 %), according to www.thearda.com. Others include Hindus, Confucians, and members of other faiths.

The significance of religions in Southeast Asia is not only in their strong presence in the daily life of society, but also in the profound role they play in various aspects of political, economic, and social life of the Southeast Asian peoples. In previous decades, it was predicted that due to the strong modernization of Southeast Asia –like in other parts of the world– religion would disappear from public life. However, the turn of the twenty-first century has seen a resurgence in religious activity. Despite predictions of its decline, religion has revived (and, some scholars add, become radicalized) around the globe, including in Southeast Asia. It has not died out in our modern world, as secularization theory anticipated, but, on the contrary, it is blossoming. Some scholars even call the 21st century “God’s century” (Toft et al. 2011).

Religious issues occupy a strategic, challenging position in the political, economic, and social life of Southeast Asian countries. Intra- and interreligious tension and conflict arise frequently in the region and, to varying degrees, persecution based on religious identity has been reported in some ASEAN member states (Human Rights Resources Center at UI Jakarta 2015). The conflict between Buddhist majority groups in Myanmar supported by the government and the Muslim minority Rohingya has led to the displacement of Rohingya refugees to camps inside Myanmar and to other other ASEAN countries (Suaedy& Hafiz 2015). These problems show the complexity of identity issue, including religious identity issue, in Southeast Asian countries and beyond. Acts of religious inspired terrorism have been making the problems more complex.

Meanwhile, as shown by the consensus of the ASEAN Economic Community which was launched this January 2016, the concerns of ASEAN leaders have focussed mostly (to not say merely) on economic interests. We do have the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration which pays attention to civil, political, and cultural rights and the people’sright to peace, but it pays little attention to religious rights. The ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights advocates for the rights of migrants, women, children, and disabled people, but had done little in regards to religious rights. It seems the actors try to avoid religious issues.

Thus, it is necessary to ask such questions as where is the place for talking about inter/ intra religious issues in the public life since religion isin fact part of public discourse? Who will initiate opening that discussion? What is the role of public (non-theological, non-religious vocational) universities in this region on these issues?

In this article, I will try to answer the last question based on the assumption that the answer must indirectly respond to the preceding questions. I look at how public universities in Southeast Asian countries are initiating the academic study of religions during the last two decades by opening centers or departments with the title religious studies or similar names.

Of course, religions have long been studied widely in universities in the region, usually from the perspective of theology or as the (social) science of religion within such disciplines as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and so on. It is important to differentiate among the three positions: theology, (social) science of religion, and religious studies, which tends to be interdisciplinary in its approach. My main concern here is religious studies.

Let us come to see the institutional development of religious studies in several universities in Southeast Asia. I focus on three institutions, among others as examples. First,the College of Religious Studies in Mahidol University in Thailand was established in 1999 and dedicated to “the study and research in the field of religious studies [that]fosters mutual understanding, cooperation, and respect among people of different religious traditions”. A strong International Center for Buddhism and Islamis part of that college. (http://www.crs.mahidol.ac.th/).

Second, at GadjahMada University Indonesia, the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS) interdisciplinary master program focusing on religious studies was established in 2000. It has three main areas of study: inter-religious relations; religion, culture and nature; and religion and public life (crcs.ugm.ac.id).

Third, it is a little surprising that in 2014 Nanyang Technological University in Singapore also opened a master program entitled “Studies in Inter-Religious Relations in Plural Societies” within its Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). It is mentioned in its profile that it “aims to study various models of how religious communities develop their teachings to meet the contemporary challenges of living in plural societies. It will also deepen the study of inter-religious relations, formulate models for the positive role of religions in peace-building and produce knowledge to strengthen social ties between communities” (www.rsis.edu.sg/research/srp/).

These aforementioned institutions offer academic degrees in religious studies (BA, MA, and/ or PhD). The main character of religious studies as each defines it is strengthening inter-religious perspectives. In consequence, the religious studies approach draws directly or indirectly on comparative studies within religious diversity either as social context or as a primary concern of study. In this point we can see one major difference in perspective and positionality between religious studies and theology.

Thus, on one hand, it is in line with the duty of the public university to understand about diverse religions rather than to preachon behalf of one religion. In addition those institutions are engaged in peace movements and other activities related to diversity management in their respective societies. In this point, the religious studies perspective, by seeking to be impartial but not neutral, is different from that of the science of religion that usually –not always—strives to be neutral.

In conclusion, considering the awkwardness of public universities and other public bodies and authorities within ASEAN in ‘addressing’ religion, it is clear that it is time to look at religious studies as an alternative approach. Religious studies recognizes the significance of religion in Southeast Asian political, economic, and social life. Maybe it is not an over statement to say that the centers and departments of religious studies in Southeast Asian public universities –in cooperation with other disciplines– will be new players in relation to the management of religious diversity in the public life of Southeast Asia.

The writer is a lecturer at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS),

Graduate School, GadjahMada University, Indonesia.

He can be reached at: suhadi_cholil@ugm.ac.id

Azis Anwar Fachrudin | CRCS | Opinion

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”15″]Fatwa MUI telah digunakan orang-orang intoleran untuk mempersekusi yang difatwa sesat[/pullquote] Sebagaimana mutakhir diberitakan, Majelis Ulama Indonesia (MUI) Pusat hendak menyusun beberapa kriteria tentang ajaran sesat, khususnya ajaran yang “mencaci-maki Sahabat Nabi Muhammad SAW, menolak kepemimpinan al-Khulafa’ ar-Rasyidun, dan memperbolehkan nikah mut’ah.” Kriteria ini jelas diarahkan kepada Syiah, yang sebagian telah menjadi korban tindakan kekerasan.

Maka kini adalah waktu yang tepat, bahkan mendesak, bagi MUI—yang susunan pengurus barunya diduduki oleh orang-orang berpendidikan tinggi—untuk mengkaji lagi perannya dalam konteks kenegaraan. Sebagai organisasi yang tak sepenuhnya dapat dipisahkan dari negara, MUI memiliki tanggung jawab kewargaan (civic) untuk memperhitungkan dampak fatwa-fatwanya bagi setiap warga negara Indonesia, termasuk yang dianggap sesat. Di tahun-tahun belakangan, beberapa fatwa MUI tentang kesesatan suatu kelompok tak selalu membantu tumbuhnya hubungan antarkelompok yang lebih baik. Fatwa MUI malah kerap digunakan sebagai justifikasi kekerasan. Tantangan utama MUI adalah mengedepankan paradigma moderat sebagaimana disampaikan sendiri oleh Ketua Umumnya.

Fatwa untuk Mazhab yang Sah

Yang pertama kali perlu dipertimbangkan adalah, kalaupun fatwa itu akan dikeluarkan, jangan sampai di-gebyah-uyah atau dipukul rata untuk semua orang Syiah. Bagi para penebar propaganda “Syiah bukan Islam” atau “Syiah kafir”, semua Syiah dianggap sama; semua Syiah dianggap Rafidhah; semua Syiah di mana dan kapan saja dikira berkeyakinan dan berperilaku sama. Ironisnya, orang-orang penyebar propaganda takfiri itu tak mau bila organisasi seperti Taliban, al-Qaeda, dan ISIS dijadikan representasi Ahlus-Sunnah (Sunni) dan semua Sunni dianggap sama belaka dengan mereka—kecuali bagi orang-orang yang memang menjadi pendukung gerakan-gerakan barbar itu.

Sudah sering diulang-ulang, bahkan bagi beberapa orang mulai agak klise, argumen-argumen bahwa Syiah merupakan mazhab dan bagian yang sah dalam Islam. Upaya institusionalisasi “pendekatan antarmazhab” (at-taqrib bayn al-madzahib) sudah diinisiasi lebih dari setengah abad lalu oleh ulama al-Azhar. Sejak saat itu, fikih Syiah-Ja’fariyah diakui sebagai bagian dari delapan mazhab fikih Islam yang legitimate dan masuk dalam kitab-kitab fikih perbandingan mazhab yang dikaji di universitas-universitas Islam bercorak Sunni. “Risalah Amman” yang menyerukan keabsahan dan persaudaraan mazhab-mazhab Islam (Sunni, Syiah, Salafi) sudah mengudara sejak 2005 dan dideklarasikan oleh ratusan ulama dan intelektual Muslim terkemuka sedunia, tak terkecuali dari Indonesia.

Jika menginginkan argumen yang lebih gampang: Orang-orang Syiah bersyahadat, salat, membayar zakat, puasa saat Ramadan, dan bisa berhaji ke Mekkah—kurang lebih 15 persen dari sekitar 16 juta penduduk Arab Saudi adalah orang Syiah. Argumen yang lebih gampang lagi: Iran, yang mayoritas Syiah itu, adalah anggota Organisasi Kerjasama Islam (OKI) yang sekretariatnya kini ada di Arab Saudi; dan konferensi ke-8 OKI pada 1997 diselenggerakan di Teheran, Iran. Ini mestinya sudah cukup untuk mengatakan bahwa Syiah memang bagian dari Islam.

Jika menginginkan argumen yang lebih gampang: Orang-orang Syiah bersyahadat, salat, membayar zakat, puasa saat Ramadan, dan bisa berhaji ke Mekkah—kurang lebih 15 persen dari sekitar 16 juta penduduk Arab Saudi adalah orang Syiah. Argumen yang lebih gampang lagi: Iran, yang mayoritas Syiah itu, adalah anggota Organisasi Kerjasama Islam (OKI) yang sekretariatnya kini ada di Arab Saudi; dan konferensi ke-8 OKI pada 1997 diselenggerakan di Teheran, Iran. Ini mestinya sudah cukup untuk mengatakan bahwa Syiah memang bagian dari Islam.

Atau, supaya lebih dekat dengan Indonesia, sudah banyak tokoh-tokoh Muslim Indonesia baik dari Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) maupun Muhammadiyah yang menyatakan Syiah adalah mazhab yang sah dalam Islam, seperti Kiai Hasyim Muzadi, Kiai Said Aqil Siradj, Buya Syafii Maarif, Prof. Amien Rais, dan Prof. Din Syamsudin (yang kini menjadi ketua dewan pertimbangan MUI). Yang termutakhir, Syaikh al-Azhar Ahmad at-Thayyib datang ke MUI belum lama ini dan melarang mengkafirkan semua orang Syiah secara umum berdasar pada prinsip “la nukaffiru ahadan min ahl al-qiblah” (“kita tak mengkafirkan seorangpun dari ahli kiblat”). Tak bisa pula dilewatkan, kedatangan Syaikh al-Azhar ke MUI itu bersama ulama Syiah Lebanon, Sayyid Ali al-Amin.

Stigma-Stigma Klasik

Berangkat dari argumen-argumen di atas, jika MUI mau mengeluarkan fatwanya, seharusnya itu mengerucut pada tindakan saja, misalnya soal “mencaci-maki Sahabat”, dan tidak digeneralisasikan kepada ke-syiah-an secara umum. Menjadi Syiah tak serta merta berarti pencaci Sahabat, sebagaimana menjadi Sunni tak serta merta berarti memiliki keyakinan yang sama dengan Taliban, al-Qaeda, dan ISIS; atau, lebih sempit lagi, menjadi Salafi tak serta merta berarti “Salafi-Jihadi”.

Hal yang sama juga berlaku untuk stigma-stigma lainnya yang kerap ditempelkan pada Syiah. Di antara stigma klise itu, misalnya, bahwa Syiah memiliki al-Quran yang beda dari Sunni. Ini satu stigma yang tidak ada bukti fisiknya (al-Quran yang terbit di Iran sama dengan al-Quran yang dibaca kaum Sunni) dan hanya didasarkan pada riwayat di kitab klasik Syiah tertentu. Tapi naas, beberapa kaum takfiri memilih bebal dalam soal ini. Padahal bila mau balik bercermin, standar penilaian yang sama sebenarnya juga bisa diberlakukan terhadap Sunni: Dalam kitab-kitab hadis Sunni—yang pasti sudah diketahui para kiai dan cendekiawan MUI—terdapat hadis yang menginformasikan bahwa dulu ada ayat tentang rajam dalam al-Quran tapi hilang dimakan kambing (ini terkenal dengan sebutan “hadits ad-dajin”) dan bahwa dulu surah al-Ahzab (kini 73 ayat) panjangnya sama dengan surah al-Baqarah (286 ayat). Pun demikian, dengan berbekal hadis-hadis ini seseorang tak serta merta bisa menyimpulkan bahwa al-Quran yang dibaca Sunni sudah mengalami tahrif (distorsi) dan/atau semua Sunni berkeyakinan bahwa al-Quran saat ini sudah tidak asli.

[pullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”15″]Orang-orang Islam yang tidak menyukai standar ganda politik Barat dalam mendiskreditkan umat Islam seperti ini sudah seharusnya tidak melakukan standar ganda yang sama[/pullquote]

Hal yang sama juga bisa diberlakukan untuk kasus nikah mut’ah. Benar bahwa pandangan ortodoksi Sunni mengharamkan nikah mut’ah sejak masa Khalifah Umar ibn al-Khatthab. Namun hadis di Sahih Muslim merekam bahwa nikah mut’ah pernah boleh di zaman Nabi, lalu dilarang, lalu boleh lagi, dan kemudian baru dilarang untuk selamanya oleh Khalifah Umar. Ada pernyataan menarik dari Imam as-Syafi’i tentang hal ini: “La a’lamu fil-Islam sya’ian uhilla tsumma hurrima tsumma uhilla tsumma hurrima ghayra ‘l-mut’ah, Aku tak tahu sesuatu dalam Islam yang dihalalkan lalu diharamkan lalu dihalalkan lalu diharamkan selain nikah mut’ah.” (Dengan ini maka beberapa kaum takfiri yang menyatakan bahwa nikah mut’ah sama dengan zina berarti telah menyatakan suatu klaim yang berbahaya: itu klaim yang berimplikasi bahwa Nabi pernah membolehkan zina!)

Di sini, sekali lagi, yang penting ialah untuk tidak melakukan generalisasi dan standar ganda. Akan lebih baik bila bisa mengakomodasi keragaman pandangan dalam Syiah, juga memperhatian isu-isu paralelnya dalam Sunni untuk berkaca: jangan-jangan yang dituduhkan kepada Syiah itu memiliki basis atau preseden yang mirip dalam literatur klasik Sunni sendiri. Yang lebih penting lagi ialah memiliki sejumput empati: sebelum suatu standar dipakai untuk menilai kelompok lain, pakailah standar itu terlebih dulu kepada kelompok sendiri.

Hal itu karena tendensi tekstualisme tampak kuat dalam cara MUI mengolah fatwa. Maksudnya ialah kecenderungan berpikir “bila statemen X disebut secara literal di kitab kelompok Y maka berarti kelompok Y otomatis meyakini X.” Ketahuilah bahwa ini juga cara berpikir kaum Islamofobia di Barat. Islam di Barat, oleh kaum Islamofobis, dianggap agama yang mengajarkan kekerasan semata-mata karena terdapat ayat-ayat dalam al-Quran yang, setidaknya bila dibaca secara sekilas, memerintahkan tindak kekerasan (misalnya, QS 2:191; 4:89; 9:5 & 29). Dalam aspek ini, cara sebagian kaum anti-Syiah di sini memperlakukan Syiah memiliki paradigma yang mirip dengan kaum Islamofobis memperlakukan umat Islam di Barat. Oleh karena itu, MUI seharusnya tidak mengadopsi paradigma semacam itu.

Fatwa Bukan Sekadar “al-Bayan”

Hal lain yang seharusnya menjadi catatan bagi MUI ialah bahwa fatwa-fatwanya dapat menjadi alat pembenar untuk mempersekusi mereka yang difatwa sesat. Dalam situasi ketika sekelompok warga negara menjadi korban kekerasan, fatwa tentang kesesatan mereka justru memperburuk situasi. Sebagaimana ditunjukkan beberapa riset, fatwa MUI juga dapat melemahkan kerja penegak hukum ketika menghadapi kelompok-kelompok pelaku kekerasan terhadap kelompok yang difatwa sesat. Inilah yang terjadi dalam kasus persekusi terhadap Ahmadiyah (di Bogor pada 2005, di Kuningan hingga 2010, dan Lombok Barat pada 2006). Dalam kasus di Sampang, fatwa tentang kesesatan Syiah dikeluarkan MUI Jawa Timur justru setelah komunitas Syi’ah di Sampang menjadi korban penyerangan. Ini seperti memberi alat pembenar kepada massa untuk membakar properti, melukai dan mengusir ratusan orang Sampang dari desanya (yang kini sudah lebih dari 3 tahun ditempatkan di Sidoarjo).

Ironisnya, ketika terjadi tindak persekusi dan kekerasan yang menjadikan fatwa MUI sebagai alat legitimasi, MUI cenderung lepas tangan, seakan-akan fatwa sesatnya tidak berkontribusi dan tidak mengandung ‘saham dosa’ sama sekali. Dalam kasus penyerangan sadis terhadap warga Ahmadiyah di Cikeusik yang mengakibatkan kerusakan properti berharga dan tiga orang Ahmadi meninggal, MUI tampak cenderung menyalahkan Ahmadiyah dan menolerir tindakan intoleran massa. Dan ketika para pembunuh dalam kasus Cikeusik itu dihukum hanya antara tiga sampai enam bulan, tak ditemukan komentar kecaman dari MUI atas ketidakadilan itu. Lebih dari orang awam, para kiai di MUI mestilah tahu bahwa membunuh tanpa hak merupakan dosa besar.

Dalam kasus Sampang, ketua komisi fatwa—dan kini sudah ketua umum—MUI, Kiai Ma’ruf Amin, sebagaimana ditulisnya dalam artikel di Republika (8/11/2012), mengafirmasi fatwa MUI Jatim tentang Syiah. Kiai Ma’ruf mengatakan bahwa fatwa MUI dalam soal akidah dimaksudkan “sebagai panduan dan bimbingan kepada umat tentang status paham keagamaan yang berkembang di masyarakat”. Fungsi fatwa, katanya, ialah sebagai “al-bayan atau penjelasan”. Namun yang terjadi, fatwa MUI Jatim dipakai oleh pengadilan setempat untuk mempidanakan dan memvonis Tajul Muluk dengan hukuman 4 tahun penjara.

Dengan kata lain, Fatwa MUI ternyata bukan sekedar “al-bayan” sebagaimana disampaikan Kiai Ma’ruf, tapi telah digunakan orang-orang intoleran untuk mempersekusi yang difatwa sesat dan, lebih fatal dari itu, diadopsi oleh pemerintah hingga seolah-olah memiliki kekuatan hukum mengikat. Yang terakhir ini telah dilakukan belum lama ini ketika walikota Bogor, Bima Arya, melarang peringatan Asyura.

Mencegah Normalisasi Intoleransi

Persepsi publik yang cenderung tak membedakan antara fatwa sebagai pendapat yang tak mengikat dan vonis pengadilan, lebih-lebih undang-undang, adalah aspek yang harus dipertimbangkan dalam pengolahan fatwa MUI. Tanpa mempertimbangkan ini, alih-alih bisa meminimalisasi penyebaran ‘aliran sesat’, MUI justru berkontribusi terhadap digunakannya fatwanya untuk menzalimi orang lain. Dengan kata lain, bermaksud memberantas kemungkaran tapi melahirkan kemungkaran baru berupa persekusi dan kekerasan. Dalam aspek yang terakhir ini MUI telah digeret—baik oleh orang MUI sendiri maupun pemerintah terkait—melampaui proporsi yang semestinya sebagai lembaga non-pemerintah (yang juga bukan ormas, dan karena itu tak setara dengan NU dan Muhammadiyah). Fatwa MUI, semua tahu, tidak memiliki status hukum dalam tata aturan perundang-undangan negeri ini.

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”black” class=”” size=”15″]Wasathiyyah (moderatisme) berarti kesediaan untuk berdialog dan bernegosiasi, serta berkompetisi secara fair dan memperlakukan kelompok lain, termasuk yang dianggap sesat, dengan adil. [/pullquote]

Dengan rentannnya fatwa MUI digunakan sebagai justifikasi tindak kekerasan, semestinya MUI punya fatwa khusus tentang fatwa sesatnya. Pertanyaannya bisa dirumuskan, misalnya, begini: Bolehkah fatwa sesat jadi legitimasi untuk melakukan tindakan vigilantisme atau main hakim sendiri dan melangkahi kewenangan negara? Bila jawabannya tidak, maka sudah seharusnya MUI berfatwa tentang itu. Bunyi fatwa itu bisa dibuat misalnya begini: “Barangsiapa menggunakan fatwa MUI untuk membenarkan tindakan vigilantisme maka tindakan itu juga sesat.” Dengan fatwa seperti ini, MUI menegaskan bahwa ia tidak berlepastangan dari tindak intoleran yang menggunakan fatwanya.

Hal yang terakhir ini sangat penting, mengingat yang terjadi di Indonesia akhir-akhir ini ialah adanya gejala normalisasi tindakan intoleran terhadap mereka yang difatwa sesat. Yakni, ketika orang-orang yang difatwa sesat dilukai, dibunuh, dihancurkan propertinya, dan diusir hingga harus mengungsi di negeri sendiri, dan pada saat yang sama para pelaku kezaliman malah bebas atau dihukum ringan dan tak setimpal. Normalisasi membuat kezaliman seperti ini jadi fenomena yang tampak ‘wajar’.

Normalisasi semacam ini jelas tak bisa dibenarkan, baik ditinjau dari perspektif negara yang berasaskan “keadilan sosial bagi seluruh rakyat Indonesia” maupun dari perspektif Islam yang di antara tujuan syariatnya ialah menjaga properti (hifzhul-mal) dan menjaga hidup (hifzhun-nafs). Normalisasi semacam ini pulalah yang terjadi dalam diskursus di Barat: ketika suatu kejahatan dilakukan Muslim, istilah ‘terorisme’ cepat mengemuka dan tampil dalam headline media, sementara ketika ia dilakukan non-Muslim maka dianggap kejahatan ‘biasa’. Orang-orang Islam yang tidak menyukai standar ganda politik Barat dalam mendiskreditkan umat Islam seperti ini sudah seharusnya tidak melakukan standar ganda yang sama: bila suatu kesalahan dilakukan orang yang dianggap sesat maka dibesar-besarkan (dan kadang dicari-cari untuk membunuh karakternya), sedangkan persekusi dan kezaliman yang dilakukan orang-orang intoleran dipandang ‘lumrah’.

Masa Depan MUI: Wasathiyyah?

Mengeluarkan fatwa bisa dipandang sebagai hak, namun pada akhirnya, lebih merupakan tanggungjawab kewarganegaraan MUI. Sebelum fatwa sesat dikeluarkan, belum terlambat untuk berbenah. Juga merevisi fatwa-fatwa yang lampau atau fatwa-fatwa diskriminatif di tingkat daerah. Kalau perlu bahkan MUI bisa melakukan “reformasi dan pembaruan”, sebagaimana istilah yang tercantum dalam website MUI tentang misinya: “sebagai gerakan al-ishlah wat-tajdid”. Kiai Ma’ruf Amin bahkan pernah menyatakan bahwa MUI harus berparadigma wasathiyyah, yaitu keislaman yang mengambil “jalan tengah (tawassuth), berkesimbangan (tawazun), lurus (i’tidal), toleran (tasamuh), egaliter (musawah), mengedepankan musyawarah (syura), berjiwa reformasi (ishlah), mendahulukan yang prioritas (awlawiyyah), dinamis dan inovatif (tathawwur wa ibtikar), dan berkeadaban (tahaddhur).” Klaim semacam ini terasa indah didengar, tapi akan kehilangan makna bila tanpa bukti—dan terbukti/tidaknya akan segera terlihat agaknya tak lama lagi.

Wasathiyyah (moderatisme) berarti kesediaan untuk berdialog dan bernegosiasi, serta berkompetisi secara fair dan memperlakukan kelompok lain, termasuk yang dianggap sesat, dengan adil. Moderatisme berarti mengupayakan titik temu, alih-alih titik tengkar dengan mengobarkan api sektarianisme yang belakangan sedang memanas. Moderatisme juga meniscayakan adanya pendekatan dan ishlah yang, selain bermakna reformasi, juga berarti rekonsiliasi secara damai. Jika tidak, alih-alih ishlah, yang mungkin terjadi adalah ifsad (menebar kerusakan).

Penulis adalah mahasiswa Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (CRCS), UGM, angkatan 2014.

Azis Anwar Fachrudin | CRCS | Article

In two consecutive days of this week, the world’s two biggest religions commemorate the birth of their respective “founders”: Islam’s Prophet Muhammad (Maulid) and Christianity’s Jesus Christ (Christmas). This is certainly a rare event that will not happen for dozens of years to come.

In Indonesia, both commemorations have officially been declared national holidays. Indonesia is among most Muslim-majority countries in which Maulid constitutes a national public holiday. It is only in Saudi Arabia and Qatar, out of all Muslim majority countries, where Maulid is not a holiday, probably because of the views of clerics there who regard Maulid celebration as Islamically illegitimate and bid’ah (heretical). Besides, Indonesia is among several Muslim-majority countries that recognize Christmas as a national holiday.

This is a momentous time for both Muslims and Christians to reinforce interfaith dialogue — it probably could be incorporated in the agenda of the commemorations.

For Indonesians in particular, it is worth being grateful that the annually held debate among people at the grassroots — on whether saying “Merry Christmas” to Christians is religiously allowed for Muslims — is coming to an end. Additionally, another annual debate on whether Muslims may celebrate Maulid has generally begun decreasing.

In fact, these two debates on Maulid and Christmas are mostly fueled by Wahhabist views. Across the Muslim world, it is mostly the Wahhabists who claim that saying “Merry Christmas” is tantamount to affirming Christian belief on Jesus’ divinity and as such forbidden.

And why is the debate now not as heated as in the previous years? I heard a satirical comment in social media saying that it is because the Wahhabists are nowadays preoccupied with declaring the Shiites infidels. A plausible explanation! The sense of “feeling threatened” has now been shifted from Christians to Shiites, as well as to communists (whose political party no longer exists).

As for interreligious dialogue, now is a good time to recall and to remind Muslims and Christians of the document, A Common Word Between Us and You, which was launched in 2007. Originally an open letter to the Catholic pope, it has now been signed by hundreds of the world’s leading Muslim scholars and intellectuals (it can be accessed at acommonword.com). The document basically conveys that there are more common grounds for peace between Muslims and Christians than conflicting teachings. The document was then responded to by Loving God and Neighbor Together: A Christian Response to A Common Word, which was initially signed by more than 300 Christian leaders and scholars.

These kinds of documents should be more endorsed by respective leaders, clerics and scholars, for at least two reasons. First because, particularly in Indonesia, the document seems to be less exposed to the public. Second, nowadays we see a rising intolerance in the respective worlds. The rise of Islamophobia in the West, not only in Europe but also in the US given the recent phenomenon of presidential hopeful Donald Trump, is a good example.

On the other side, the Muslim world is now suffering from radicalization, resulting in the emergence of the Islamic State (IS) movement. This is why peace-building and tolerance activists should work harder to win the discourse in the respective worlds, including for example by exposing their respective communities to the documents.

As for the Muslim world, the Maulid commemoration can be a good time to reread the Prophet’s biography, not only to praise or glorify him but also to deal with how we should understand his having been a leader of wars in today’s context. Around the globe, Muslims usually celebrate Maulid by reciting salawat (prayers) or madah nabawi (a kind of eulogy to praise the prophet). In Indonesia particularly, Muslims recite books containing Arabic poetry of salawat or madah nabawi.

I think that in today’s context such a reading of the Prophet’s biography, while good, should be furthered with rereading about the violence surrounding his life. This is important because some Muslims who do violence nowadays quite often justify their acts by citing examples of the violence commanded by the prophet.

Prophet Muhammad, unlike Jesus, was a leader in war. He was involved in nine wars. Furthermore, he dispatched military expeditions at least 38 times. Some early biographers of the Prophet emphasized this aspect; this is why their books were entitled Maghazi (literally “wars”) and it became a genre of biography at the time. All these wars left hundreds of victims and happened during eight years from 2 AH to 9 AH, a period in the last phase of Muhammad’s prophetic ministry when Muslims became quite powerful.

How then should today’s Muslims read those wars led by the Prophet? This has very much to do with Islamic jus ad bellum, especially on what circumstances violence can be justified under Islamic teachings. Rereading these, I think, is more important as a counter interpretation of violent Muslims rather than saying normatively that “Islam is a religion of peace” or that “rahmatan lil-‘alamin” (“the prophet was sent as a mercy for all creatures”).

Azis Anwar Fachrudin | CRCS | Article

Is it possible and necessary to have voices from Islam that are both against and for a moratorium on the death penalty? I think it is necessary, as what shapes discourse in the Muslim communities of Muslim-majority countries can influence policies in those countries. In Indonesia, for instance, an interpretation of sharia promoting a moratorium on the death penalty has been raised, but it is unfavorable to many Muslim scholars.

Amid the uproar concerning the death penalty for Indonesian migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, as well as that of drug convicts in Indonesia, opposing voices in the name of Islam are barely heard. Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia, considered moderate by many, condemned the death penalty for migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, yet supported the death penalty for drug convicts. But in general, the death penalty is a non-issue for Islamic organizations.

Amid the uproar concerning the death penalty for Indonesian migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, as well as that of drug convicts in Indonesia, opposing voices in the name of Islam are barely heard. Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia, considered moderate by many, condemned the death penalty for migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, yet supported the death penalty for drug convicts. But in general, the death penalty is a non-issue for Islamic organizations.

First, this is maybe because death penalty cases in general scarcely touch the issue of Muslim identity politics — many so-called secular Muslims are on both sides of the debate. Second, capital punishment, along with corporal punishment, is prescribed in Islamic scripture so it is very difficult, though not impossible, to have a voice of Islam that is against the death penalty.

However, 21st century Muslims should review the practices of the death penalty in Muslim-majority countries and this can be done even within the realm of Islamic teachings or sharia. Here are the premises.

Sharia by many Muslims nowadays is reductively understood in terms of legalistic formulae. Sharia is associated with corporal and/or capital punishment, as if sharia is nothing but a penal code and punishments. Yet sharia literally means the way or path. In Koranic terminology, it means the path toward an objective representative of the supreme virtue of Islam, which is justice (some would add dignity of human beings and mercy and love for all creatures).

Muslim scholars, ranging from reformists, rationalists, even literalists, would agree that the supreme value promoted by Islam when it comes to dealing with relationships among individuals and/or communities is justice, as explicitly stated and commanded by God many times in the Koran. The mercy that Islam would bring to the world is justice.

Any action leading to injustice, in whatever name, including in the name of Islam, is therefore un-Islamic and should be opposed by Muslims. All Islamic legal opinions that are against justice are thus against the sharia of Islam.

As God has commanded Muslims to be “bearers of witness with justice”, as the Koran states, Muslims should share the notion once voiced by Martin Luther King Jr. that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”. All unjust punishments should be an Islamic issue, including questions over the death penalty of Indonesian migrant workers and foreign and local drug convicts.

Now, the question is how justice is manifested in punishment. The traditional fiqh (Islamic law and jurisprudence) is still lacking discussion of the philosophy of justice compared to advanced discourse in the secular realm, which has led to the concept of restorative justice, distinguished from retributive justice. The idea of qisas (an eye for an eye) is mostly understood as a deterrent and/or equal retaliation within retributive justice.

Nevertheless, Muslim scholars advocating a moratorium on the death penalty are echoing these arguments: corporal punishment, stoning or the death penalty cannot be implemented within an unjust system of governance, judiciary, or an unequal society, given the fact that those punishments are irreversible.

In this view, a just system is a prerequisite of such irreversible punishments. An unjust system is considered one of the shubuhat (ambiguities) based upon which the irreversible punishment must not be applied, as the Prophet Muhammad said. Included in that unjust system are dictatorships that are still embraced by many Muslim-majority countries, where the weak and poor are more likely to be punished than the wealthy and powerful.

That is the argument posed by some NU leaders in criticizing Saudi Arabia’s death penalty for Indonesian migrant workers, given frequent reports of torture and other dehumanizing practices by employers.

With regard to restorative justice, Mutaz M. Qafisheh from Hebron University in the International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences wrote that Islamic jurisprudence had many alternatives to original punishments known in modern restorative justice systems, such as compensation (diya), conciliation (sulh) and pardon (afw). These mechanisms are stated in the Koran and were exemplified by the Prophet. Qafisheh also says that classical Muslim scholars had unique mechanisms derived from the wider principles of Islam that can be understood as restorative means, such as repentance (tawba), intercession (shafaa), surety (kafala) and expiation (kafara).

He concludes: “By looking at the philosophy of penalty as detailed by Islamic jurisprudence […] restorative justice does exist. It exists as the general rule. Retributive justice is the exception.”

That kind of reinterpreting of Islamic scripture should be advanced by today’s Muslim scholars if Muslims want to be able to respond to the discourse of international human rights.

Also, for the Muslims who are so obsessed with the rules textually prescribed in the scripture, we should consider the notion that God’s revelation is not only in the text (ayat qauliyyah) but exists also in the universe (ayat kauniyyah), in the way human beings behave. Modern sociology and criminology should be juxtaposed and mirrored with traditional fiqh by Muslim jurists in their interpretations of the scripture.

Azis A. Fahrudin | CRCS | News

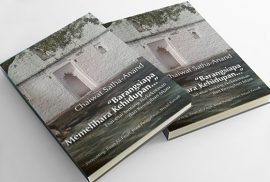

The writer is a graduate student of CRCS batch 2014. This article is his response to Chaiwat Satha-Anand’s compilation articles published by PUSAD Paramadina, Jakarta and his lecture at CRCS on October 8, 2015.

T he book by Chaiwat Satha-Anand entitled “Barangsiapa Memelihara Kehidupan…” consists of a number of essays dealing with, as the subtitle of the book suggests, “nonviolence and Islamic imperatives.” The book seeks to propose theological arguments for nonviolent Islam. Many parts of the book are, thus, filled with Quranic verses and stories and quotes cited from the prophetic traditions which, according to Satha-Anand’s interpretation, support the idea of nonviolent Islam. However, the way he constructs theological arguments is not rigorous enough, especially in consideration of the fact that the position of scripture (both the Quran and the hadiths) toward violence and peace is ambiguous and multi-faceted, a position which in turn brings about complexities of interpretation. This article, thus, serves as a response to Satha-Anand’s ideas of nonviolent Islam as explained in the book. It discusses, first, violence in the scripture, both in the Quran and the prophetic traditions, to show the multi-faceted accounts and some difficulties in interpreting them. Second, it draws several points which should be taken into consideration in dealing with that complexity of interpretation—including in showing the ambivalence of the scripture. In the end, it points out that, besides proposing nonviolent interpretations of Islam, the way the perpetrators of violence perceive the surrounding reality they face must be given equal attention in the discussion.

he book by Chaiwat Satha-Anand entitled “Barangsiapa Memelihara Kehidupan…” consists of a number of essays dealing with, as the subtitle of the book suggests, “nonviolence and Islamic imperatives.” The book seeks to propose theological arguments for nonviolent Islam. Many parts of the book are, thus, filled with Quranic verses and stories and quotes cited from the prophetic traditions which, according to Satha-Anand’s interpretation, support the idea of nonviolent Islam. However, the way he constructs theological arguments is not rigorous enough, especially in consideration of the fact that the position of scripture (both the Quran and the hadiths) toward violence and peace is ambiguous and multi-faceted, a position which in turn brings about complexities of interpretation. This article, thus, serves as a response to Satha-Anand’s ideas of nonviolent Islam as explained in the book. It discusses, first, violence in the scripture, both in the Quran and the prophetic traditions, to show the multi-faceted accounts and some difficulties in interpreting them. Second, it draws several points which should be taken into consideration in dealing with that complexity of interpretation—including in showing the ambivalence of the scripture. In the end, it points out that, besides proposing nonviolent interpretations of Islam, the way the perpetrators of violence perceive the surrounding reality they face must be given equal attention in the discussion.

Kelli Swazey | CRCS

Kelli Swazey is a lecturer and faculty member of CRCS.

Saya ingin memulai dengan berbagi cerita tentang pengalaman saya enam bulan yang lalu. Suatu malam dalam perjalanan pulang ke rumah, saya sendirian naik motor dan saya menjadi korban perampokan di Ring Road Utara. Syukurlah, ada para pekerja yang sedang memperbaiki sebuah hotel yang terletak di pinggir jalan tempat saya mengalami perampokan malam itu. Para pekerja itu menyelamatkan saya, karena ketika saya jatuh dari motor, saya sempat pingsan. Orang yang menyelamatkan saya meminta maaf berulang kali. Seperti banyak orang lain yang mendengar cerita tentang musibah yang saya alami, mereka merespon dengan kecurigaan bahwa orang yang menyerang saya pasti orang pendatang. Ternyata, orang-orang yang merampok saya adalah dua anak muda dari Sleman. Salah satu pelakunya masih ABG, berumur sekitar usia anak SMA. Selama diopname di rumah sakit, saya tidak habis pikir dan bertanya pada diri sendiri apa motivasi mereka.

Saya ingin memulai dengan berbagi cerita tentang pengalaman saya enam bulan yang lalu. Suatu malam dalam perjalanan pulang ke rumah, saya sendirian naik motor dan saya menjadi korban perampokan di Ring Road Utara. Syukurlah, ada para pekerja yang sedang memperbaiki sebuah hotel yang terletak di pinggir jalan tempat saya mengalami perampokan malam itu. Para pekerja itu menyelamatkan saya, karena ketika saya jatuh dari motor, saya sempat pingsan. Orang yang menyelamatkan saya meminta maaf berulang kali. Seperti banyak orang lain yang mendengar cerita tentang musibah yang saya alami, mereka merespon dengan kecurigaan bahwa orang yang menyerang saya pasti orang pendatang. Ternyata, orang-orang yang merampok saya adalah dua anak muda dari Sleman. Salah satu pelakunya masih ABG, berumur sekitar usia anak SMA. Selama diopname di rumah sakit, saya tidak habis pikir dan bertanya pada diri sendiri apa motivasi mereka.

Rachmanto

Alumnus CRCS

Sejak pekan kemarin, rombongan haji dari Yogyakarta sudah mulai berangkat ke tanah suci untuk melaksanakan ritual suci tahunan ini. Suatu ibadah yang membutuhkan beragam pengorbanan baik harta maupun jiwa. Tidak heran ibadah haji menjadi simbol kesempurnaan seorang Muslim. Akan tetapi ibadah haji ternyata tidak hanya berpengaruh bagi ketaqwaan pribadi seorang Muslim. Ibadah haji bahkan bisa meningkatkan ketaqwaan kolektif dalam konteks kebangsaan. Ritual haji mampu menanamkan sekaligus menumbuhkan benih-benih kebangsaan dalam diri pelakunya.

Sejak pekan kemarin, rombongan haji dari Yogyakarta sudah mulai berangkat ke tanah suci untuk melaksanakan ritual suci tahunan ini. Suatu ibadah yang membutuhkan beragam pengorbanan baik harta maupun jiwa. Tidak heran ibadah haji menjadi simbol kesempurnaan seorang Muslim. Akan tetapi ibadah haji ternyata tidak hanya berpengaruh bagi ketaqwaan pribadi seorang Muslim. Ibadah haji bahkan bisa meningkatkan ketaqwaan kolektif dalam konteks kebangsaan. Ritual haji mampu menanamkan sekaligus menumbuhkan benih-benih kebangsaan dalam diri pelakunya.

Nicole Laux is one of English instructors at CRCS for periode 2010 to 2012 from the United State. For two years she had been living in Yogyakarta and starting to use a motorbike. From her motorbike she observed how people live in the city which has many names: the city of culture, the city of education, the city of tolerance, the city of young people, and the city of motorbike. In her writing for Shansi, the instituion that sent her to Yogya, she share what life looks like from a motor cycle, as she wrote below:

Nicole Laux is one of English instructors at CRCS for periode 2010 to 2012 from the United State. For two years she had been living in Yogyakarta and starting to use a motorbike. From her motorbike she observed how people live in the city which has many names: the city of culture, the city of education, the city of tolerance, the city of young people, and the city of motorbike. In her writing for Shansi, the instituion that sent her to Yogya, she share what life looks like from a motor cycle, as she wrote below:

When it rains in a motorbike riding country people sometimes stop on the side of the road and wait it out, but I would say most people want to get to their final destination, so they put on a poncho. As much as I hated driving in the rain, and hated having to put on my blue-plastic- shin-length-perpetually-moldy-smelling- sort- of- slimy- when – I-forget- to-dry-it –out-poncho, I liked the 20 second adrenalin rush I got when I was trying to get into my poncho as fast as I could. I got pretty good. If I was at a stop light and the green light countdown was at 30 seconds I knew that I could dismount my bike, take off my helmet, open my seat, take out my poncho, and put it on, and still have 10-5 seconds to get my helmet back on and turn on my bike. It’s almost like me and all the drivers were super heroes changing into our crime fighting outfit to fight the oppressive rain. Once the masses have their ponchos on, there is a sea of plastic capes flapping behind the lone drivers, families of 2-4 huddled under one or two ponchos, and the best, couples on bikes with two headed ponchos looking like a two headed alien”.

Read the whole story at here

Suhadi Cholil* | CRCS |

Freedom of the press in the era of the Reformation, although much more open than in the New Order, to borrow Endy Bayuni’s phrase, in the field of religious journalism, journalists is still difficult to harness the freedom to support the equal civil rights of citizens. It is seen from the results of a survey conducted Yayasan Pantau (Monitor Institution) relating to the perceptions of Indonesian reporter towards Islam in 2012. A survey of 600 journalists in 16 provinces showed the higher tendency of Indonesian journalists who identify themselves as Muslims rather than as Indonesia. This identification has implications for the strong bias of the journalists while reporting violence to the minority groups. This is evident from the use of words that tend to judge as “misguided”, “should be forsworn”, and others. I think this bias arises because the journalist is difficult to distinguish between the personal religious arenas to the professional position as a journalist. This paper examines further some of the findings, not all of them due to space limitations, from the results of the survey held by Yayasan Pantau (Monitor Institution).

BetweenThe Objectivity and the Religiosity

Humans, including journalists, are multi-dimensional figure and complex. Meanwhile, journalism and religion are two different fields or arenas (Bourdieu 1992). As shown by the Pantau’s survey, Indonesian journalists are generally difficult to distinguish between those two arenas. This is evident from: first, the high percentage of journalists who identify themselves as “religious Muslims” (50.6% in 2009 and 43.3% in 2012). Second, from the answer to the question, “above all, I am …”. A total of 41.5% said Islam, 38% answered Indonesia, and only 11.8% who answered as the reporter. Third, the high number of respondents (66.5%) agreed that the task of journalists, among others, is “to protect the Islamic tradition”. Additionally the strong Islamic identity of respondents is indicated by their proximity (58.7%) in the two mainstream Islamic organizations in Indonesia, NU (42.1%) and Muhammadiyah (16.6%).

The situation that may be very difficult resulting in mixing the arena or the domination of religious arena over journalism arena is seen from: first, the high support for journalists to Law No.1/PNPS/1965 on prevention, abuse, and defamation of religion (76.5%). Second, there is a high support for the Joint Decree (Surat Keputusan Bersama -SKB) on Ahmadiyah (56%). Third, there is a high support for the fatwa MUI 2005 on the banning of Ahmadiyah (59%).