Maria Lichtmann | CRCS | Article

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”13″] “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”13″] “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.”

-CRCS’ Student- [/perfectpullquote]

Teaching the course on “Religion, Women, and the Literatures of Religion” was one of the highlights of my teaching career. From the first day, when I stepped into the classroom and was greeted with smiles and welcomes, I knew I could feel comfortable bringing what I knew and wanted to teach to these students. This class of students had already been seasoned and prepared to be a community of learners by having studied the better part of the year in this unique program. I did not detect the kind of competitive edge that is so much a feature of classroom interaction in the United States, and I feel that has something to do with the culture here of long-standing collaboration and sharing. It was certainly evident in the way these students worked together, laughed together, and enjoyed time after class, such as in “buka puasa,” the opening of the fast that comes during Ramadhan. Coming from various parts of this vast country, from Medan on the island of Sumatra, from Aceh, from the small island of Lombok, as well as many cities around Java, they also represented diverse religious backgrounds, the majority Muslim, but also Protestant Christian and Catholic Christian (the one Catholic being a Sister of Notre Dame whom the students had come to see as “ibu,” Mother). About three-fourths of the students were male, and although that might have seemed an impediment to learning almost the entire semester only about women, these young men showed no signs of resistance, and in fact demonstrated an amazing openness and willingness to engage the issues confronting women in the Midldle Ages as well as today.

What was just as impressive to me was that they were reading and writing academic studies in English, a discourse that can be difficult even for native speakers! They stretched themselves in so many ways that it was truly admirable, and I know many of them struggled. Despite that, they produced response papers that were for the most part readable and intelligent, some brilliant. I heard so many new insights from their unique perspectives, and they helped me to look at these works by medieval and modern women with new eyes.

The content of the course consisted primarily of writings from Christian mystics and visionaries of the Middle Ages, as well as a thesis written on Sufi women mystics. We encountered the remarkable prison diary of St. Perpetua, martyred in 203 C.E., and marveled over the multi-talented abbess, musician, poet, prophet, mystic, Hildegard of Bingen, discussed food in the writings of the unique medieval women’s group, the Beguines, and then focused on the book, Showings, written by Julian of Norwich. I would like to include here some of the comments students made when reading her beautiful treatise, to give some idea of how open they were to learning across boundaries of time, gender, and theology:

“Her style of contemplating God is set in the fourteenth century, but the meaning is still alive and meaningful today and invites us to share in that same trustworthy love. “

“Showings reveals a woman who experienced God directly and as “our mother.”

“Her revelations of the feminine side of God are a very significant contribution to all of us now.”

“God’s grace and divine love through a feminine figure is such an empowerment and encouragement for all beings, not only women. Also men, because the feminine qualities show how simply love can comfort and heal, just like a mother’s love.”

“The dualism of feminine/ masculine no longer exists in Julian’s understanding of God. God is feminine, and at the same time also masculine. The human/body and the divine, the feminine and masculine, each of both is actually a union.”

I was very happy to have CRCS’ alumna, Najiyah Martiam’s Master’s Thesis on Sufi women, based on her interviews with three women connected to pesantrens, in order to balance what could have been an over-emphasis on the Christian tradition, the one I know best. We also had a chance to invite another CRCS alumna, Yulianti, a Buddhist scholar who happens to be a friend of mine. Yuli helped explain how the female lineage in Theravada Buddhism died out, and has not been restored because the line was broken.

I was very happy to have CRCS’ alumna, Najiyah Martiam’s Master’s Thesis on Sufi women, based on her interviews with three women connected to pesantrens, in order to balance what could have been an over-emphasis on the Christian tradition, the one I know best. We also had a chance to invite another CRCS alumna, Yulianti, a Buddhist scholar who happens to be a friend of mine. Yuli helped explain how the female lineage in Theravada Buddhism died out, and has not been restored because the line was broken.

Two of the most exciting, energizing classes were led Dewi Chandraningrum, the editor of Jurnal Perempuan (Indonesian Feminist Journal), who brought us readings from her edited volume, Body Memories. I was very happy to have Bu Dewi’s presence in the classroom, and to see the student’s immediate warm responses to her as she sometimes spoke in Bahasa Indonesia, the language most accessible for them. In her first class, she divided the students into three groups, in discussion of three topics relating to the female body: menstruation, sexual intercourse, and childbirth. What could have been a class of silence, embarrassment, or even giggles, became a serious, mature conversation among the students. I was awed by their willingness to discuss such sensitive topics together, with mixed genders. Bu Dewi’s second class introduced us to the women activists of Kartini Kendeng, and the opposition to the proposed cement factory that has already decimated villages and their way of life in northern Java.

I would like to say in conclusion, that based on the readings from the women mystics like Julian of Norwich, whose theology of the body is holistic, non-dualist, and healthy, and intensified in the sessions led by Bu Dewi, this class became almost a spirituality of the body. Sacred sexuality and the sacredness of the female body became an underlying theme. I will let one of the students have the last word by quoting from his final paper: “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.” This student and others showed me at what depth of understanding they were interpreting what they read and heard. They were a gift and joy to teach!

____________________________

Maria Lichtmann is a Fulbright fellow to Indonesia. She taught “Women, Religion, and Literatures” in intersession semester at CRCS from June to July, 2016. She is a former professor of Religious Studies at ASU and currently teaching at Widya Sasana, Malang.

Abstract

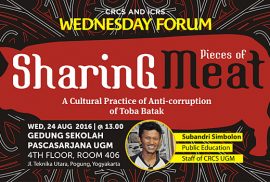

Corruption is a problem of civilization which, by extension, is a problem of culture. This must be confronted by reviving the cultural values of anti-corruption. Learning from local traditions which combat corruption can be a powerful instrument to fix corrupt tendencies in a state. Strong beliefs in local cultural values can become the base of these efforts. In other words, the culture will create the people, and the people will create the civilization. Presenter try to offer an overview of Mambagi Jambar (Sharing Pieces of Meat) activity as representative of the cultural activities which combat corruption. By basing on ethnographic interviews and analysis of related texts, the presenter will describe this discussion in a systematic matter. The first part introduces global corruption and, furthermore, the issue of corruption in Indonesia. The second part describes the activities of padalan jambar juhut in Toba Batak culture. The last part then discusses these activities and their contributions in an effort to revive anti-corrupt cultural practices.

Speaker

Subandri Simbolon is Public education Staf at CRCS-UGM. His research, focused on culture and populer issue, has been published in globethic.net journal. He finished his BA at Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat dan Teologi (STFT) Widya Sasana Malang where he majored in Christian Philosophy. In 2014, he graduated from CRCS-UGM where focuse on Culture and Ecology. In 2014 and 2015, he awarded the first winner for globetthic.net essay competition about “Anti Corruption Ethics and Religiosity (2014) and “Responsible Leadership (2015)“.

Abstract

Corruption is a problem of civilization which, by extension, is a problem of culture. This must be confronted by reviving the cultural values of anti-corruption. Learning from local traditions which combat corruption can be a powerful instrument to fix corrupt tendencies in a state. Strong beliefs in local cultural values can become the base of these efforts. In other words, the culture will create the people, and the people will create the civilization. Presenter try to offer an overview of Mambagi Jambar (Sharing Pieces of Meat) activity as representative of the cultural activities which combat corruption. By basing on ethnographic interviews and analysis of related texts, the presenter will describe this discussion in a systematic matter. The first part introduces global corruption and, furthermore, the issue of corruption in Indonesia. The second part describes the activities of padalan jambar juhut in Toba Batak culture. The last part then discusses these activities and their contributions in an effort to revive anti-corrupt cultural practices.

Speaker

Subandri Simbolon is Public education Staf at CRCS-UGM. His research, focused on culture and populer issue, has been published in globethic.net journal. He finished his BA at Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat dan Teologi (STFT) Widya Sasana Malang where he majored in Christian Philosophy. In 2014, he graduated from CRCS-UGM where focuse on Culture and Ecology. In 2014 and 2015, he awarded the first winner for globetthic.net essay competition about “Anti Corruption Ethics and Religiosity (2014) and “Responsible Leadership (2015)“.

Robina Saha | CRCS | Article

Robina Saha is a Shansi Fellow to Indonesia. She taught english at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University Yogyakarta from August 2014 – to June 2016.

Robina Saha is a Shansi Fellow to Indonesia. She taught english at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University Yogyakarta from August 2014 – to June 2016.

I first visited the city of Banda Aceh in the spring of 2009. As I stepped out of the airport and drove into town, I was greeted by a quiet Indonesian city framed by a gorgeous vista of mountains to the south, glittering coastline in the north, and tranquil rice paddies in between. Smooth, wide roads and fresh-faced buildings were the most telling signs of the city’s destruction at the hands of the 2004 tsunami and the investment that flowed into Aceh in its wake. The hotel where I stayed displayed photos of boats that had crashed into houses miles away from shore, some of which remain in situ today as memorials and tourist attractions. But it was hard to map these images of debris and desolation onto the clean, quiet little space I traversed between the hotel and the public school where I taught for a week.

At sixteen, I knew little about Aceh apart from its destructive encounter with the tsunami. Although I was born in Indonesia and lived in Jakarta for the first six years of my life, Aceh was geographically, culturally and politically as far removed as any other country. Until 2005, the region had been embroiled in a bloody conflict between the Indonesian military and the separatist Free Aceh Movement; at the time, travel to Aceh was rare and required special permits. Growing up in metropolitan cities where headscarves were rare and the vast majority of Indonesians I knew were from the island of Java, Aceh was something we only heard about on the news in relation to sharia law and ongoing violence. Looking back, I went to Aceh with an image not dissimilar to the one most Americans have of the Middle East, or Indians of Kashmir: Islamic fundamentalism and destruction.

Upon actually arriving in Banda Aceh, I felt a little foolish for being surprised, half-expecting to be accosted by the sharia police at every corner. While all the Indonesian women wore jilbabs (headscarves), I was never made to feel uncomfortable for leaving my frizzy nest of hair exposed. If anything, in a city more accustomed to Western NGO-workers, my face and arms were of interest mainly in order to determine whether I was possibly related to any Bollywood stars (specifically: Kajol; answer: I wish). Like many cities in Indonesia, there are mosques on every street, and I enjoyed seeing the variety of styles and sizes, from simple neighbourhood masjids to the toweringly beautiful Baiturrahman Grand Mosque. At prayer time, the entire city, warungs and all, would shut down, often leaving us to order room service nasi goreng or head to the lone Pizza Hut where we would sip on bottles of Coca Cola and wait it out.

In other words, my prevailing impression of Banda Aceh was of a quiet, conservative, and surprisingly lovely Muslim city populated by Indonesians just as friendly, curious and warmly hospitable as any other I’ve met. Later, upon reflection, I realised that as a visiting foreigner it was easy to glance over the strict policing of moral codes when I wasn’t the target. I never crossed the sharia police in their khaki uniforms, prowling the streets in pick-up trucks and lying in wait at roadblocks in search of unmarried Indonesian couples and uncovered Muslim women. After reading more about the region’s turbulent history, I came to appreciate that I had barely scratched at the surface layer of a city grappling with the process of constructing a contemporary social and political Islamic identity. The after-effects of a natural disaster popularly viewed as a punishment from Allah for decades of civil war had etched themselves far more deeply in the Acehnese psyche than I could have shallowly perceived.

Although I was born in, come from, and grew up in countries with significant Muslim populations, this was in many ways my first conscious confrontation with the blurred convergences between the Islam I saw in the media and what I observed on the ground. At times it can feel like staring at a double-exposure, trying to figure out where one image ends and the other begins. Looking back, although I wouldn’t have said it at the time, many of the decisions I made over the next six years—learning Arabic, studying Islamic culture and politics, writing my senior thesis on the post-9/11 display of Islamic art in Western museums, and ultimately coming back to Indonesia as a Shansi Fellow—could potentially be traced back to this first encounter with contemporary Islam and the questions it sparked in my mind about the representations and realities of Muslims around the world.

When I was first offered the Jogja fellowship in November 2013, I was deep in the process of writing my senior thesis, which was in part a critique of the Islamic art field for its exclusion of most non-Middle Eastern Islamic cultures. Having grown out of European colonial paradigms of Islam, the Middle East and Asia, what we call “Islamic art” is largely limited to the art and architecture of the Arabian Peninsula, Central Asia, Iran, Turkey and India. Islam first arrived in Southeast Asia through trade as early as the 12th century, and today the region makes up a quarter of the world’s Muslim population. It’s also one of many areas that are conspicuously absent from introductory textbooks, museum displays and courses of Islamic art. Specifically in the case of Indonesia, this too can be traced back to the impact of Dutch colonial scholarship, which focused on the archipelago’s Hindu and Buddhist heritage at the expense of its contemporary Islamic culture—partly as a way to delegitimize local Islamic resistance groups. Over time it became an accepted truth that Islamic cultures outside of the European-defined Orient were simply a corruption of the “real” Islam.

In a post-9/11 context where the international image of Islam is largely informed by the puritanical Wahhabism propagated by Saudi Arabia and the fundamentalist extremism carried out by ISIS, I argued in my thesis that the inclusion and visibility of Islamic culture from traditionally peripheral regions like Southeast Asia in displays and discussions of Islamic culture would help challenge the common misconception of a singular Islam located solely in the Middle East. At 200 million and counting, Indonesia has the single largest population of Muslims in the world, and yet most people would struggle to find it on a map. The Islamic culture that developed and spread here in the 15th and 16th centuries is certainly different and more syncretic in character due to its intermixing with pre-existing Hindu and Buddhist religions of the time. But to me this speaks more to the diversity of Islam across the world than the predominance of a single, “original” interpretation that has come to dictate the mainstream international discourse.

Jogja, as the heartland of Javanese culture and the seat of the last major Muslim kingdom in Java, with a majority-Muslim population and a thriving contemporary art scene, presented what seemed like a perfect opportunity to test the ideas I had put forward in my thesis. Despite having grown up in Southeast Asia, I still knew shamefully little about its history of Islamic culture, and I was about to spend two years in the heart of it all. This time, I wanted to come prepared with questions that would frame my thoughts and conversations here.

In the last 15 years, it seems that Indonesia has undergone a sharp Islamic revival, particularly among the younger middle-class generation. When my family left in 1999, it was still relatively rare to see women wearing jilbabs; indeed, for decades, the government had actively discouraged it as a threat to the pluralism that is enshrined in Indonesia’s political doctrine. These days, it’s uncommon for Muslim women not to wear one. Everyone I spoke to in the weeks leading up to my departure, from professors to old family friends, warned of increasing Muslim conservatism, even in a relatively liberal university town like Jogja. I was sharply reminded of my pre-Aceh expectations and the lessons I had learned since, but nonetheless packed a few scarves just in case.

The truth, as always, is a little more complicated. Islam here is certainly more visible than it has ever been. Schools are increasingly adopting policies that emphasise Islamic religious practices and uniforms, even in public universities. In any of my classes, out of roughly twenty-five students it’s rare to see more than two girls without a jilbab. According to a Muslim feminist activist I met a few months ago, this is a marked change from the Suharto era, when jilbabs were banned on school grounds and students and teachers alike could be expelled for wearing one. Wearing a jilbab in the Suharto days, it seems, became a form of symbolic resistance to the regime.

And yet, for many of the young Muslims I meet in Jogja, overt religious piety seems to function more as a public uniform that marks their identity and allows them to fit in. I still remember meeting my friend Imma at a café late one night, who turned out to be a student at the graduate school where I teach. Dressed in a chic powder-pink blouse, she wore her hair uncovered in a pretty shoulder-length bob. Upon discovering that I worked on the same campus as her, she grinned conspiratorially at me and said, “You probably won’t recognise me at school because I usually wear a jilbab.” When I responded with a confused blink, she laughed, explaining that she views the jilbab as a formal uniform for campus the way we wear blazers and heels to work in the West. As a Muslim woman she exercises her right to choose to cover up without compromising her beliefs. For her and her female Muslim friends, choosing not to wear the jilbab has become the new form of public resistance.

It was easy for me to think of Imma and her friends as an exception to the rule. Yet over the past two years I’ve met so many young Indonesians with their own approaches to the way they practice Islam, ranging from Muslims who cover their hair to those who sport chic haircuts; Muslims who identify as queer, gay and transgender; Muslims who have ringtones reminding them to pray during the day yet still drink alcohol at night. As I’ve come to know these people over extended karaoke sessions and late night café hangouts, it’s become clear that the way they practice their faith also constitutes a rejection of the idea of a single interpretation of Islamic law and culture.

A few months ago, Indonesia attracted international attention when it was featured in a New York Times article that described a film made by Nadhlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest Muslim organisation, which denounces the actions of ISIS and promotes tolerance—or, as the author Joe Cochrane puts it, “a relentless, religious repudiation of the Islamic State and the opening salvo in a global campaign by the world’s largest Muslim group to challenge its ideology head-on.” The film is designed to introduce the world to NU and Islam Nusantara, or Indonesian Islam, as a tolerant and moderate alternative to fundamentalism and Wahhabist orthodoxy, rooted in traditionalist Javanese approaches.

Islam in Indonesia certainly can provide a model for tolerance and pluralism within a global Islamic framework. And like any other religious society, it also has its own tensions and fault lines. In Jogja it’s common for pro-LGBT and feminist events and film screenings to be shut down or cancelled by threats from radical groups like the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) and the Front Jihad Islam (FJI). Many of these communities have been forced underground, and news is most often spread by word of mouth for fear of retaliation. My friends have been threatened and beaten at parties where the police have stood by and watched as FPI thugs lay waste to the venue. Just a few months ago, the city was plastered with anti-LGBT propaganda, and Pondok Pesantren Waria Al Fatah, an Islamic school for transgender Muslims, was forced to shut down amidst waves of extremist-led homophobic rallies.

In discussions about Islam and extremism, I often hear non-Muslim friends, family and colleagues calling upon Muslim communities to reject Islamic fundamentalism. That it is the responsibility of the moderate Muslims of the world to provide proof that they exist, to drown out the noise of radicalism that has dominated the airwaves. I’ve always felt uncomfortable with this idea because it ignores the fact that Muslims themselves are already the single largest victim of fundamentalist violence and oppression. For every beating, cancelled event and anti-progressive demonstration, there are Indonesian Muslims fighting back on the ground and on social media, rejecting the actions of these groups as un-Islamic—a word that continues to shift its meaning every time it is used.

Last December, I went back to Aceh to visit the Shansi fellows there. In many ways it was like being there for the first time; there was so much more to see and learn about beyond my limited initial experience. This time, armed with a motorbike, friends on the ground, and the ability to speak Indonesian again, I could finally start to fill in the outlines sketched in my mind six years ago with colour and complexity. One thing I didn’t notice the first time was the absence of cinemas, which were banned across Aceh under post-tsunami sharia law; men and women are not allowed to sit together in dark spaces, and foreign films are considered too promiscuous for Muslim audiences. The nearest movie theatre is in Medan, a fourteen-hour bus ride south.

Yet Acehnese film culture is far from dying. One night while we were staying in Banda Aceh, my co-fellow Leila was asked to judge a few short documentaries made by local filmmakers. We drove to a small studio tucked away on in a quiet street corner, where a group of young Muslim men greeted us with salak fruit and bottles of water. The corridor outside the screening room was lined with posters of short films and documentaries that, it turned out, had been organised and often produced by the same group. They provide resources for young filmmakers, run workshops, and organise screenings and programs like the Aceh Film Festival, which features short films and documentaries from Aceh, Indonesia and abroad. When I asked about the ban on cinemas, they expressed frustration at being unable to screen their films in a local theatre, but it hasn’t deterred them. If anything, the indie film scene has flourished in the wake of conservatism both in quantity and quality; Acehnese films are increasingly gaining recognition at national and international festivals.

In the six years I’ve spent studying Islamic culture and politics, I’ve learned that every one of these seeming contradictions constitutes a small part of the fascinating picture of the global religious, political and cultural phenomenon of Islam. When we allow the rich variety of opinions, practices and traditions across Islam’s broad geographic spread to be reduced to a single interpretation, we lose the shades of variation between depths and shallows, beauty and ugliness, tolerance and extremism. These last few months in particular—revisiting Aceh, travelling to Kashmir for the first time, and witnessing Jogja struggle visibly with surges of intolerance—have served to reinforce the importance of experiencing the broad spectrum of Islam firsthand. And the Islam I encounter in Jogja is as different from Acehnese Islam as it is from Kashmiri Islam, or Saudi Arabian Islam, or Iranian Islam.

I came to Indonesia with so many questions about Islam, and I will almost certainly leave it with just as many. But living here, witnessing the different facets of Islam Nusantara everyday has forced me to continuously confront my conceptions of Islam in a way that simply studying it from afar never could. Learning to recognise, understand and embrace these distinctions, contradictions and complexities has been a defining theme not only of my fellowship, but my entire understanding of contemporary Islam. Wherever my life takes me after Shansi, I hope I can continue to encounter Islam in all its various, beautiful, troubling, complex forms.

This article also published in http://shansi.org/

George Sicilia| CRCS | Artikel

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”14″]“Di Indonesia, kita sudah terbiasa dengan situasi yang heterogen, beda dengan Eropa. Tetapi dengan intensitas perjumpaan yang semakin tinggi dan iklim yang demokratis, sekarang kita pun, harus belajar ulang bagaimana mengelola keragaman itu.”[/perfectpullquote]

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”14″]“Di Indonesia, kita sudah terbiasa dengan situasi yang heterogen, beda dengan Eropa. Tetapi dengan intensitas perjumpaan yang semakin tinggi dan iklim yang demokratis, sekarang kita pun, harus belajar ulang bagaimana mengelola keragaman itu.”[/perfectpullquote]

JAKARTA, 11 Juni 2016 – Bertempat di LBH Jakarta, pertemuan ketiga Sekolah Guru Kebinekaan (SGK) – YCG berlangsung dengan penuh semangat. Teman belajar para guru kali ini adalah Dr. Zainal Abidin Bagir dari Center of Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS)-UGM. Topik SGK kali ini adalah Penguatan Keragaman, Kebangsaan dan Kemanusiaan melalui Nilai Agama, Adat, Hukum dan HAM. Karena keluasan topik, fokus utama adalah nilai Agama. Agama di sini tidak sekadar nilai atau teks suatu agama, tetapi dalam pemahaman yang lebih luas yang memungkinkan orang-orang dari latar belakang yang berbeda untuk berada bersama-sama.

Perjumpaan adalah modalitas

Pak Zainal mengawali dengan merefleksikan pengalamannya mengajar di CRCS. Program Studi yang didirikan paska momentum Reformasi itu memang istimewa karena pada masa itu terjadi banyak sekali konflik yang beberapa di antaranya bernuansa agama. Beragam orang dari latar belakang agama, etnis, disiplin keilmuan juga motivasi datang untuk belajar bersama-sama. Beberapa di antaranya datang dengan prasangka. Tetapi satu hal yang pasti menurut beliau, hal yang sangat penting dan mahal harganya adalah mengupayakan pertemuan-pertemuan antara orang-orang yang beragam, yang membuat mereka mampu melangkahi pemikiran awalnya dan melihat yang berbeda sebagai sesama manusia. Sayangnya hal ini kurang terfasilitasi dalam sistem pendidikan agama di sekolah-sekolah.

“Karena semua yang ada di sini adalah pendidik dan ketika bicara pendidikan tidak hanya pengajaran, dan salah satu strategi pendidikan adalah mempertemukan orang dengan segala macam keterbatasan, termasuk keterbatasan struktur dan sistem. Kalau ada satu poin penting yang perlu saya sampaikan sebagai refleksi pengalaman saya adalah kemampuan untuk bersikap kritis. Dan saya kira salah satu tujuan pendidikan adalah bersikap kritis. Bukan tentang kemampuan mengkritik, tetapi kemampuan melihat satu isu dari berbagai sudut pandang dan tidak menerima segala pengetahuan dan informasi mentah-mentah, tapi dipikir ulang dan dilihat dari berbagai sisi. Tujuan terpenting prodi kami adalah mempersiapkan orang berpikir kritis melihat realitas”, kata Bagir.

Kebangkitan Identitas Agama dan Meningkatnya Keragaman Agama

Ada dua hal yang ditengarai saat ini yaitu kebangkitan identitas agama dan meningkatnya keragaman agama. Hal ini bukan hanya terjadi di Indonesia saja, tetapi juga di Eropa dan beberapa negara lainnya. Identitas agama tiba-tiba menjadi penting untuk ditampakkan dalam 15-20 tahun terakhir. Cara orang beragama saat ini atau ekspresi yang ditunjukkan dalam busana berbeda dengan satu atau dua dekade yang lalu. Mungkin tak begitu disadari oleh generasi saat ini, tetapi pasti terasa perubahannya bagi angkatan-angkatan sebelumnya.

Keragaman agama juga meningkat. Bukan tentang pertambahan jumlah, tetapi bahwa migrasi di berbagai tempat telah membuka jalan bagi masuknya berbagai hal dari tanah asal ke tempat yang baru. Mulai dari sekadar kuliner, hingga budaya dan agama. Beberapa agama yang sebelumnya sudah ada tetapi tidak tampak di permukaan, di iklim demokrasi ini juga mulai menampakkan wajahnya. Kemudahan transportasi, informasi, membuat jarak semakin sempit dan batas-batas mengabur.

Orang-orang di Eropa selama ini terbiasa dengan kehidupan yang cenderung homogen. Tetapi dengan migrasi yang semakin banyak, Eropa harus beradaptasi dengan dunia yang semakin heterogen. “Di Indonesia, kita sudah terbiasa dengan situasi yang heterogen, beda dengan Eropa. Tetapi dengan intensitas perjumpaan yang semakin tinggi dan iklim yang demokratis, sekarang kita pun, harus belajar ulang bagaimana mengelola keragaman itu”, ungkap Bagir. Ruang besar untuk berekspresi dalam demokrasi, turut diisi dengan ragam ujaran kebencian. Indonesia memiliki Bhinneka Tunggal Ika tetapi tantangan semakin besar, sehingga ini adalah saatnya mempertanyakan lagi kemampuan kita mengelola keragaman.

“Sekarang kita diuji betul, apakah kita benar-benar toleran atau tidak karena ini ruang besar untuk agama menunjukkan dirinya”, katanya lagi terkait ambivalensi agama.

Berpikir Kritis Menyikapi Ambivalensi Agama

Sisi negatif dalam cara orang beragama dapat berupa penghilangan hak orang lain hingga kekerasan. Namun, ada juga potensi besar kebaikan agama seperti saling memperkaya dan juga saling menguatkan nilai-nilai kebaikan dan kehidupan. Berbicara agama memang tidak harus hanya melihat sisi negatif tetapi juga potensi kebaikan yang berperan besar bagi orang yang meyakini agama tersebut dan memberi dampak sosial.

Tantangannya tentu saja, kita perlu memahami ambivalensi atau ke-mendua-an potensi agama, agar dapat meminimalisir yang negatif dan memperkuat potensi kebaikan agama. Agama tidak hidup dalam ruang vakum yang sebatas ajaran dan teks semata, tafsir agama pun sebenarnya beragam, selalu bertemu dengan konteks sosial politik yang bisa mendukung potensi kebaikan agama ataunpun sebaliknya. Tafsiran yang beragam itu pun bisa tereduksi, menjadi tidak seimbang. Jadi ketika bicara ke-mendua-an, ada soal konteks dimana berbagai persoalan karena agama tidak selalu karena agama itu sendiri, tetapi hal lain atau pertemuan teks dan konflik. Bersikap kritis menjadi sangat penting di sini!

Membicarakan toleransi dan intoleransi, tidak selalu karena agamanya toleran atau tidak, tetapi bisa juga karena kebijakan negara. Di Indonesia ada keluhan masyarakat jadi lebih tidak toleran, mungkin bukan karena masyarakat, tetapi juga ada peran negara. Di setiap masyarakat selalu ada kelompok yang ekstrim dan intoleran, di masyarakat paling demokratis sekalipun. Sampai pada tingkat tertentu tidak apa-apa, orang tidak harus suka pada setiap orang. Itu baru menjadi masalah ketika negara membiarkan dan memberi ruang yang besar bagi orang bersikap intoleran sehingga jadi arus lebih kuat. Itu intoleransi karena negara.

Memang lembaga atau pemimpin agama pun, disadari atau tidak, bisa memainkan peran yang mengarah pada sisi negatif atau pada potensi kebaikan. Pada momen-momen seperti pilkada, kadang agama dijadikan alat atau disebut juga instrumentalisasi agama. Kita perlu selalu berpikir ulang dan kritis melihat konteks agama.

Tetapi sebagaimana dikatakan sebelumnya, selalu ada potensi kebaikan dalam agama. Sebagian besar agama yang punya akar yang mirip. Di antaranya agama kerap muncul untuk mengupayakan keadilan sosial. Jarang agama dimiliki sekelompok orang kaya, justru agama kritis terhadap kelompok yang berkuasa sehingga para nabinya dikejar, dipersekusi, dsb. Itu cerita yang mirip dalam banyak agama. Agama dapat merespon isu-isu kontemporer dengan kembali pada nilai profetik mula-mula yaitu membela orang tertindas, mempertahankan keutuhan ciptaan Tuhan, memperjuangkan keadilan sosial. Itu adalah potensi dalam inti agama yang sulit dipisahkan.

Aturan Emas (Golden Rules)

Golden rule itu simpel. Kurang lebih, jangan lakukan kepada orang lain apa yang kamu tidak ingin lakukan padamu, atau lakukan pada orang lain apa yang kamu ingin orang lakukan padamu. Kemunculan agama-agama seperti Kong Hu Chu, Buddha, dan Hindu pada zaman aksial adalah karena kelelahan manusia berperang terus-menerus. Lahan untuk agama semakin subur saat Kristen, Islam, dll muncul. Juga tumbuh kesadaran soal compassion/kasih sayang/welas asih. Dalam Islam, Tuhan juga dikenal sebagai Allah Yang Pengasih dan Penyayang (compassionate).

Beberapa contoh aturan emas yang ditemukan dalam berbagai agama:

Buddha: “Treat not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful” ( Buddha, Udana-Varga 5.18)

Christianity: “In everything, do to others as you would have them do to you; for this is the law and the prophets” (Jesus, Matthew 7:12)

Confusianism: “One word which sums up the basis of all good conduct … loving-kindness. Do not do to others what do you do not want done to yourself” (Confucius Analects 15:23)

Hinduism: “This is the sum of duty: do not do to others what would cause pain if done to you” (Mahabharata 5:1517)

Islam: “Not one of you truly believes until you wish for others what you wish for yourself” (The Prophet Muhammad, Hadith)

Kalau mau diringkas lagi, salah satu istilah yang sering digunakan adalah altruisme, yaitu berbuat pada orang lain bukan karena kepentingan diri kita sendiri tapi kepentingan orang lain. Orang yang membahagiakan orang lain, intensitas kebahagiaannya jauh lebih tinggi dari pada yang membahagiakan diri sendiri walaupun keduanya sama-sama bahagia. Itu adalah contoh bahwa altruisme itu pada akhirnya kembali ke diri sendiri juga kebahagiaannya.

Hak Asasi Manusia

Dalam babak berikutnya, yang menunjukkan kemajuan jaman ini, salah satu tafsiran tentang munculnya deklarasi HAM adalah pelembagaan prinsip resiprositas. Dalam artinya, kalau saya tidak senang orang lain melakukan sesuatu pada saya, maka saya tidak akan melakukan hal itu pada orang lain. Semua orang sama-sama manusia dan ingin diperlakukan sama. Itu semangat relijius, penghargaan terhadap setiap manusia terlepas dari apapun identitasnya. HAM memang ada instrumennya, tapi ini adalah nilai kultural yang mendasari itu. Usia HAM belum ada 100 tahun sementara sejarah manusia sudah lama. Tetapi semangat seperti ini baru 100 tahun terakhir dimana orang menyepakati sesuatu untuk kepentingan bersama. Itu juga karena tingkat kekerasan yang luar biasa pada PD I dan PD II. Bisa bandingkan dengan apa yang disebut Karen Armstrong sebagai jaman aksial, dimana orang mulai lelah dengan begitu banyak kekerasan dan lahirlah beberapa jenius spiritual. PD I dan II korbannya itu luar biasa dan menggoncang kesadaran manusia, salah satu hasilnya adalah HAM sebagai institusionalisasi prinsip resiprositas.

Pengelolaan Keragaman dan Dunia Pendidikan Kita

Kalau bicara lingkup pendidikan, kita bicara pedagogi, prinsip pendidikan, tapi yang penting pula adalah ruang perjumpaan yang menghadirkan manusia sebagai manusia. Setiap orang bisa punya macam-macam prasangka dan semuanya itu tidak berubah walau menerima berbagai pengajaran. Hanya ketika orang tersebut bertemu orang lain, ia bisa melampaui identitas yang ada dan melihat yang liyan sebagai manusia. Bertemu manusia sebagai manusia.

Sistem pendidikan kita cenderung tidak memungkinkan ruang perjumpaan, maka strategi yang dibutuhkan adalah menghadirkan ruang perjumpaan tersebut. Pertemuan memang perlu dirancang, tetapi sebaiknya bersifat alamiah. Beberapa sekolah sudah mencoba mengupayakan perjumpaan dalam pelajaran agama walaupun tetap ada tuntutan memberi mata pelajaran per agama. Kalau guru mau, ruang-ruang perjumpaan itu bisa diusahakan karena ketakutan, prasangka, dan lainnya mungkin berubah karena perjumpaan.

Sekarang, siapkah kita mengelola keragaman kita dengan lebih baik?

Tulisan ini dipublikasikan di Facebook Yayasan Cahaya Guru

________________

George Cicilia adalah alumnus Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragaman (SPK) Angkatan pertama. Saat ini aktif di Yayasan Cahaya Guru.

Batas Waktu Pendaftaran: 25 Agustus 2016

Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (Center for Religious and Cross-/CRCS) Sekolah Pascasarjana, Universitas Gadjah Mada, membuka pendaftaran untuk:

Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragaman (SPK) VIII (Nasional)

04-14 Oktober 2016

Program

Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragaman (SPK) mengundang aktivis dan pengajar/peneliti yang mempunyai komitmen dalam mempromosikan pemeliharaan keragaman untuk mengikuti kegiatan ini. Program ini bertujuan untuk memperkuat kemampuan aktivis dan akademisi dalam menghubungkan antara dunia riset dan advokasi. SPK membekali peserta dengan keahlian dalam mengintegrasikan teori dan praktek dalam rangka penguatan basis pengetahuan untuk advokasi terkait isu keragaman. Setiap peserta diharapkan terlibat dalam kelompok penelitian mengenai isu-isu pluralisme di daerah masing-masing setelah selesai mengikuti sekolah ini.

Kami menerima peserta dari kalangan: