Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Class Journal

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

As an American lecturer who has been working with CRCS since 2014 through Eastern Mennonite University, Virginia, he is a very well-experienced educator as he previously spent some years teaching in Japan. Moreover, his interest in following up the up-dated global issues including religious nuances, made him familiar with framing the methods of studying religion and globalization.

Global ethics is one of the topics we discussed in the class, the last material before the end of the class. Previously, we talked a lot about globalization as a phenomenon affecting religions as well as several religious responses toward globalization. Despite the supporters of globalization, many religions seem to fearfully reject it, some even proclaiming their resistance and becoming more radical.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Therefore, to foster the stabilization of the world order from war and disputes, it is necessary to rethink globalization in ways that are more ethical and friendly to the world. On the topic discussion of global ethics, we learned about attempts by world organizations like the United Nations in generating international agreements including the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Besides, other agreements such as the Cairo and Bangkok Declarations represent local voices which to some points define human rights differently.

The difference in worldviews among international actors is interesting because each organization tries to define a global value within their own relativities. Moreover, some theories think that UN Declaration on Human Right is a Western domination over other cultures without considering cultural relativities, including religions, each of which inherits different theological and structures while at the same time sharing common values like peace, humanity, equality, and justice.

World issues indeed became valuable perspective in this class. Students are meant to not only understand theories but also keep updating their knowledge on what is happening in the recent international world. While negative influences of globalization such as war, religious radicalization, and other world disputes were discussed in the class, there is also a hope for a global agreement and bright future by sharing noble values like cooperation, justice, human dignity, and peace on global scale. The existence of world organizations and religious representatives in fostering global ethics proves the progress made towards creating world peace. The duty of students, in this case, is to contribute academically to spreading such values without neglecting the variety of cultural and religious perspectives.

*The writer is CRCS’s student of the 2016 batch.

CRCS-UGM

Ilham Almujaddidy & A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Event Report

Dialog antaragama sebagai upaya penyelesaian konflik bukan hal yang mudah dilakukan. Tidak jarang terjadi, dialog yang dimaksudkan untuk menjembatani perbedaan dan meminimalisasi konflik tidak berjalan sesuai tujuan awal, atau bahkan kontraproduktif dan menimbulkan masalah baru.

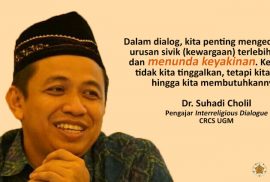

Dalam diskusi Forum Umar Kayam, Pusat Kebudayaan Koesnadi Hardjosoemantri (PKKH) UGM, pada Senin 25 Juli 2016, dosen CRCS Dr. Suhadi Cholil membahas persoalan ini. Dalam diskusi bertajuk “Menunda Keyakinan: Refleksi Membangun Pluralisme dari Bawah” itu, pengajar matakuliah Interreligious Dialogue di CRCS ini memberikan identifikasi-identifikasi penyebab dialog gagal mencapai tujuannya.

Pertama, kurangnya pemahaman substantif tentang fungsi dan metode dialog antaragama yang menyaratkan, antara lain, adanya saling percaya. Adanya praduga-praduga negatif terhadap mitra dialog dapat menimbulkan tiadanya saling percaya itu, dan pada gilirannya menjadi hambatan utama bagi efektivitas proses dialog.

Kedua, dialog antaragama yang semestinya menjadi interaksi untuk saling mengakomodasi masing-masing pihak yang terlibat, dalam prosesnya, malah terjebak dalam upaya untuk mendominasi.

Ketiga, dialog antaragama diandaikan sebagai penuntas konflik. Yang jarang dipahami, dialog dalam praksisnya tidak serta merta bisa menyelesaikan konflik. Beberapa konflik, apalagi konflik agama yang melibatkan klaim-klaim teologis yang sulit untuk dijembatani, tidak mudah dimediasi dengan dialog semata, dan karena itu memerlukan alternatif resolusi konflik yang lain.

Dengan menyadari hal-hal yang menghambat dialog antaragama itu, pemahaman yang tepat mengenai fungsi dan metode dialog antaragama bagi para pihak yang terlibat di dalamnya mutlak diperlukan, termasuk mensinergikan pengetahuan teoretis dan praksis.

Yang kerap menjadi problem di lapangan ialah banyak akademisi yang hanya fokus pada persoalan-persoalan teoretis atau teologis semata, namun abai pada ranah praktis. Sementara di sisi lain, ada banyak aktivis yang kurang reflektif secara teoretis maupun teologis, namun begitu aktif di pelbagai aktivitas dan advokasi perdamaian. Ketika kedua belah pihak ini terlibat dalam sebuah dialog, kerap kali muncul kesalahpahaman yang dapat memicu timbulnya permasalahan baru, dan karena itu kontraproduktif.

Hal lain untuk meminimalisasi hambatan dalam dialog antaragama ialah dengan mendudukkan isu teologis secara tepat. Tidak dapat dimungkiri, isu teologis merupakan isu sensitif, dan karena itu, jika tak hati-hati, justru dapat merusak proses dialog itu sendiri. Dalam proses dialog antaragama, isu teologis berada dalam ketegangan antara klaim eksklusifitas dan kehendak untuk menerima adanya keyakinan yang berbeda.

Dalam persoalan yang terakhir ini, Dr. Suhadi tidak mengusulkan untuk membuang eksklusivitas itu. Baginya, eksklusivitas itu sendiri tidak salah dalam dirinya sendiri. Ia akan menjadi masalah ketika tidak diterjemahkan dengan proporsi yang tepat di ruang publik. Banyak dari yang terlibat dalam proses dialog tidak membedakan antara ruang privat untuk ranah teologis dan ruang publik untuk pencarian titik temu guna menyelesaikan konflik. Karena kurangnya pemahaman untuk melokalisir klaim-klaim teologis pada ranah pikiran dan hati, dialog antaragama, alih-alih menjembatani perbedaan, justru rawan menjadi adu klaim teologis.

Merespons isu eksklusivitas teologis dalam dialog antaragama ini, Dr. Suhadi menawarkan gagasan bahwa untuk mengembangkan dialog antaragama yang lebih produktif, perspektif yang terbaik adalah dengan mendahulukan urusan sivik (kewargaan) dan menunda keyakinan. Hal ini tentu tidak berarti keyakinan ditinggalkan. Keyakinan ditunda, tidak dikedepankan, dan baru ditengok kembali ketika dibutuhkan dalam proses dialog.

*Laporan ini ditulis oleh mahasiswa CRCS, dan disunting oleh pengelola website.

Gregory Vanderbilt | CRCS UGM | Perspective

The kyai switched to English for just one sentence as he joined other village leaders in welcoming CRCS’s Eighth Diversity Management School or Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragaman (SPK) to the village of Mangundadi, 23 km west of Magelang, at the foot of Mt. Sumbing. Perhaps his choice was to honor the diversity present in this group—or that the chasm from ivory tower to mountain village had been bridged for an afternoon—as we tried to absorb the dance performance based on the carved reliefs of Borobudur we had just experienced. Though the village is 24km away from the 10th-century sacred site, and Muslim, it and its arts are part of the Ruwat-Rawat Festival movement that seeks to re-sacralize the great Buddhist monument from the disenchantment of the tourism industry and the weight of the busloads that climb it each day to snap selfies and admire in passing the craftsmanship of a millenium ago.

We were there because of the friendship with Ruwat-Rawat founder Pak Sucoro that has developed over the last year thanks to CRCS alumna Wilis Rengganiasih. Owner of the counter-narrative-producing Warung Info Jagad Cleguk across from the gates to the Borobudur parking lot and instigator of the eight-week festival each April-May, he had arranged an amazing afternoon for the excursion that has become an important change-of-page for SPK members after a week of ideas and passionate discussion. On the Saturday of the ten-day long school, the twenty-five members of SPK plus facilitators and friends departed by bus the school’s venue at the Disaster Oasis in Kaliurang, heading first to the warung at Borobudur to meet our guides and then heading another hour west from Magelang.

The road to the village of Mangundadi was too steep for our bus and so we were met at the main road by the pickups and motorcycles of the young men of the village. Having climbed on board, off we went to Mangundadi, the motorcycles revving their engines in a chorus of welcome. Afterwards SPK staffer Subandri admitted that he has now a tinge of positive feeling when he hears the youth gangs disrupt the city streets with their noisy machines, because what a welcome it was! When we reached the village, women lined the lane to shake our hands as we were ushered into one house to catch our breath, and then to process around the village’s new mosque with the genungan ritual mountain of vegetables, followed by the groups of performers, children, youth, adults, already in gorgeous costume and make-up. By the time we had feasted in another house, the performers were ready and, as the rain fell, they danced scenes from the stone reliefs. In the end, Pak Sucoro pulled some of us onto the stage to move with them and then they offered their salims and went back to their villages.

In the evening we returned to the Omah Semar retreat house near the monument-park for a discussion with Pak Sucoro about his vision of Borobudur as a universal spiritual heritage and as a place of spiritual significance for local culture, a place for Indonesian society to make a new choice, to live in harmony with God, nature, and each other. The Ruwat-Rawat has incorporated and re-ignited local traditions by focusing them on a global question, the question I asked the Advanced Study of Buddhism students who met Pak Sucoro back in May: who owns Borobudur? The next morning, walking across the lawns where his village once stood, we could see the stupa-monument in a new way.

In the evening we returned to the Omah Semar retreat house near the monument-park for a discussion with Pak Sucoro about his vision of Borobudur as a universal spiritual heritage and as a place of spiritual significance for local culture, a place for Indonesian society to make a new choice, to live in harmony with God, nature, and each other. The Ruwat-Rawat has incorporated and re-ignited local traditions by focusing them on a global question, the question I asked the Advanced Study of Buddhism students who met Pak Sucoro back in May: who owns Borobudur? The next morning, walking across the lawns where his village once stood, we could see the stupa-monument in a new way.

This was my third SPK since I came to CRCS in 2014. For me, it is an opportunity to meet the activists, academics, government workers, and media people who come to participate and see how change is happening across Indonesia. Each SPK may have its own character—this one, for example, was quicker to start singing than put on a mop of cringe-worthy joke telling—but the greater tone of excitement at being among others as serious of purpose and as ready to be challenged to greater intellectual depth is constant. The participants are excited by guest insights from Bob Hefner and Dewi Candraningrum but even more by the well-developed program from a core of facilitators devoted to teaching “civic pluralism” as a paradigm for just co-existence in the contexts of Indonesian diversity, one basing access in the three Re-‘s of recognition, representation, and redistribution, combined with thinking systematically about such core CRCS emphases as taking apart religion as lived and governed in Indonesia, digging into research for advocacy and putting into practice the theories and methods of conflict resolution. Equally important, they stay up late sharing their work, from teaching to preaching to activating NGOs to working conscientiously from inside government. Some know of the program because they have heard about CRCS while visiting or studying in Yogyakarta; others, following friends and co-workers who applied previously; and others still from searching online for “pluralism school” in order to serve better as religious and social leaders.

Visiting SPK alumni in their homeplaces—Jakarta, Aceh, West Sumatra, and Jambi, so far—has also shown me glimpses of grass-roots possibility across Indonesia. Trainings and workshops are regular features of Indonesian civil society, but it appears SPK leaves a more lasting impression on its participants. This is perhaps because of the intensity of their twelve days in the aptly named Disaster Oasis and perhaps because it challenges them more to take an intellectually grounded, hopeful framework to the places they are working and asks them to return with a research project, on how a pluralistically civil society is being made in soccer clubs and local studies movements and activism for gender (five from SPK-VIII work against domestic violence) and ethnic equality and film festivals and women’s economic literacy programs in villages and so on. In that way, the village kyai is right.

*The writer, Gregory Vanderbilt, is a lecturer at CRCS, teaching courses, among others, on religion and globalization; and advanced study of Christianity.

Jekonia Tarigan | CRCS UGM | SPK News

Pada hari keempat Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragamaan (SPK) angkatan ke-VIII tahun 2016 ini, tampak para peserta mulai dapat melihat muara dari upaya pendidikan yang dilakukan dalam SPK ini. Setelah beberapa hari bergaul dengan materi-materi yang menjadi landasan pembangunan kesadaran akan keberagaman dan penghargaan subjektifitas semua entitas dalam keberagaman, seperti teori identitas, reifikasi agama di Indonesia, dan lain sebagainya, para peserta dibawa ke ranah upaya mempraktikkan apa yang telah dipelajari.

Hal ini terwujud dalam topik “Advokasi Berbasis Riset” yang disampaikan oleh Kharisma Nugroho, seorang peneliti dan konsultan kebijakan-kebijakan publik dari KSI (Knowledge Sector Initiative) sebuah lembaga riset kerjasama Indonesia dan Australia yang bergerak dalam upaya mengangkat pengetahuan atau kearifan lokal dalam pembuatan kebijakan-kebijakan di tingkat daerah maupun nasional.

Dalam sesi ini disampaikan, semua peserta SPK perlu sampai pada titik di mana mereka terpanggil untuk melalukan sebuah upaya advokasi, yang secara sederhana dapat diartikan sebagai upaya memperjuangkan nilai-nilai atau ideal-ideal yang diyakini kebenarannya, misalnya mengadvokasi hak-hak masyarakat adat terhadap tanah adat mereka yang ingin dicaplok oleh perusahaan multinasional.

Namun fasilitator menekankan bahwa kerja advokasi bukanlah kerja otot (kerja keras) semata, sehingga basisnya bukan hanya emosi dan pemaksaan kehendak. Lebih dari itu, kerja advokasi adalah kerja otak (kerja cerdas), yang berarti bahwa orang-orang yang mengadvokasi harus tahu benar apa yang ia bela dan bagaimana cara membuat pembelaan dan perjuangannya itu berhasil.

Untuk itu, fasilitator menjelaskan ada tiga pengetahuan penting yang harus dimiliki oleh setiap peserta SPK, yakni: pertama, scientific knowledge, yaitu pengetahuan atau riset yang berbasis teori sebagaimana yang dapat diperoleh dalam kehidupan akademik di kampus; kedua, financial knowledge, yaitu pengetahuan atau riset yang didorong oleh lembaga-lembaga donor tertentu yang menghendaki adanya kajian tentang sebuah topik atau kejadian sebelum mereka memberikan bantuan, dll; dan yang ketiga, bureaucratic knowledge, yaitu pengetahuan terkait pemahaman pemerintah atas sebuah hal atau peristiwa yang ingin diadvokasi oleh satu lembaga swadaya masyarakat tertentu. Ini karena pemerintah mempunyai logikanya tersendiri terkait sebuah kebijakan yang akan diambil yang membuat mereka tidak hanya perlu fokus pada satu hal yang diadvokasi oleh satu LSM atau lembaga riset, tetapi juga melihat urgensi dan keberlangsungan pelaksanaan kebijakan yang akan dibuat nantinya.

Dalam SPK ini dijelaskan pula bahwa para advokator perlu menjaga kredibilitas, dengan menjaga kualitas riset. Fasilitator mengingatkan bahwa advokasi berbasis riset atau penelitian harus benar-benar teliti dan mencari terus hal-hal yang ada di balik fenomena, dan bukan hanya melihat kulit luarnya saja.

Fasilitator memberikan contoh, ada sebuah penelitian tentang program BPJS di tahun 2015 yang menyatakan bahwa pelaksanaan BPJS buruk, terjadi antrian panjang, masyarakat bingung dan kebutuhan perempuan kurang diperhatikan. Informasi ini jelas baik, namun tidak menjawab pertanyaan “apa yang menyebabkannya fenomena tersebut terjadi?” Secara sederhana, fasilitator kemudian membuat penelitian dengan memperhatikan data-data bidang kesehatan sepuluh tahun terakhir. Dari data yang dimiliki, fasilitator menemukan bahwa dalam sebuah penelitian dengan metode wawancara ditemukan bahwa masyarakat yang merasa sakit selama satu bulan hanya sekitar 25%, namun setelah adanya BPJS masyarakat menjadi lebih mudah mengakses layanan kesehatan, sehingga permintaan layanan kesehatan naik hingga 60%.

Sebelum adanya BPJS mungkin masyarakat tidak terlalu banyak mengakses layanan kesehatan dikarenakan biaya yang mahal, namun setelah ada BPJS permintaan layanan kesehatan naik hampir 100% sementara jumlah fasilitas kesehatan dan tenaga medis tidak bertambah secara signifikan. Dari hasi penelitian ini penting sekali untuk menemukan akar dari sebuah persoalan, sehingga saat dilakukan upaya advokasi isu yang dibahas adalah isu yang esensial dan dapat menjadi landasan bagi pengambilan kebijakan.

Hal lain yang juga sangat penting dari sebuah upaya advokasi adalah perubahan paradigma dari para pelaku advokasi. Advokasi tidak selalu soal mengubah undang-undang atau sebuah kebijakan. Lebih dari itu, bukti dari perubahan itu tidak pula selalu soal pendirian lembaga tingkat nasional sampai daerah yang dimaksudkan untuk menangani satu isu tertentu, sebab belum tentu perubahan undang-undang dan pendirian lembaga itu merupakan jaminan terjadinya perubahan. Bisa jadi ini justru adalah jebakan baru (institutional trap) yang menjadikan perubahan semakin lambat terjadi. Oleh karena itu, fasilitator mengingatkan ada beberapa aspek yang menandai terjadinya perubahan setelah upaya advokasi yaitu:

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Akhmad Akbar Susamto, active lecturer in in the Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) started his presentation in Wednesday Forum about Islamic and Western economics by explaining the background behind the academic discipline of Islamic economics. Islamic economics has been developed based on a belief that Islam’s worldview differs from that of Western capitalism. Islamic economics has its own perspectives and values related to how decisions are made. According to Susanto, the boundaries of Islamic economics as a social science or a discipline are closer to economics than to theology or to fiqh.

There is a strong impression telling that Islamic economics is in complete opposition with the Western conventional economics. Susanto argued that such an impression is wrong: although the Islamic worldview does differ from the worldview of Western capitalism, Islamic economics as an academic discipline was established to realize the Islamic worldview and can stand together with conventional economics established in the West. Each can benefit from the other.

Susanto introduced a new framework for Islamic economic analysis that lays a foundation for the complementarity between Islamic and conventional or Western economics. This new framework can resolve the dilemma faced by Muslim economists and help to establish Islamic academic disciplines alongside their Western peers.

This new framework introduced by UGM economists to define the scope and methodology of Islamic economics. It is called the Bulak Sumur framework. The name is taken from the name of the place where UGM is located. Based on the framework, an economy can be considered Islamic as long as it constitutes visions and methods which are consistent with Islamic worldview and it is able to help and guide societies to transform their economy towards the achievement of welfare as Islamic worldview dictates. To be Islamic requires not only separating the sacred and profane but being able to depict both the current state and the ideal state. Thus, the Bulaksumur Framework includes:

Abstract

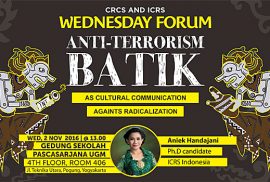

Acknowledged by UNESCO in 2009 as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, batik is produced through an introspective creative process in which the artist uncovers a truth and presents local wisdom and beauty. In this way, it can be an effective means to communicate symbols, ideas and messages about peace, respect and interreligious tolerance in order to counter the growing radicalism in Indonesian society. Aniek Handajani will present her new book Batik Antiterorisme Sebagai Media Komunikasi Upaya Kontra – Radikalisasi Melalui Pendidikan dan Budaya (co-written with Eri Ratmanto and published by UGM Press, 2016) as well as several works of batik she has commissioned in order to encourage public discussion about terrorism and peace.

Speaker

Aniek Handajani is a staff at the East Java provincial office of the Ministry of Education and an English lecturer at the Faculty of Education, Islamic University, Lamongan. She earned her Masters in Education at Flinders University in Australia and is an educator and activist for inter-religious peace. Currently, she is a Ph.D. candidate at Inter-Religious Studies (ICRS), UGM, researching terrorism and deradicalization.

Meta Ose Margaretha | CRCS | Thesis Review

In 2014, the President of Indonesia, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, released a policy addressing the “revitalization” including potential reclamation and economic development, of Benoa Bay at the southern tip of Bali. In the months that followed, there was public debate about the economic and environmental consequences of the proposal involving many sectors of Balinese and Indonesian society. Since Bali is well-known as the one majority-Hindu part of Indonesia, it was to be expected that religious identities and value also would have a significant role in the controversy. Daud Partigor’s thesis “Significances of Theological Argumentation in Rejecting the Proposed Reclamation of Benoa Bay” focuses of religious elements of the debate, including the role of religious institutions and of religious language and ideology as the legitimation for arguments opposing the reclamation of the bay. His research also shows that the debates on rejecting the proposed reclamation of Benoa Bay are part of a complicated process merging ideas of religiosity, the environment, economic interests, culture, politics and humanity in one pot. But, here also, the author tries to emphasize how religious ideas could be implemented at other levels, such as in governmental regulations to advocate the existence of Benoa Bay area.

In this case, the key theological element being promoted and argued is the concept of sacred places. Local people around the Benoa Bay consider the bay itself as a sacred space. Toward the sacred space, Balinese Hindus have their certain understanding that leads them to behave also in a certain way.

The discourse of Benoa Bay’s sacredness based on the teachings of Hindu-Bali traditions became public in early 2015. The ideas about the sacredness came from by analyzing how exclusively religiously-based arguments become explicitly used in the public discussion, the thesis offers insight into thethe revival of religion in public in a different context than Islam-focussed studies have offered.

The discourse of Benoa Bay as a sacred place is used by some organizations to advocate and protect Benoa bay from the reclamation. This study case is important because it shows how the policies made by both state and religion are influence each other. In the Bali context, the key actor is the Hindu Supreme Council or Parisada. Partigor explains how Parisada is divided between local branches and the central office in Jakarta which makes regulation and decisions for all the members of Parisada locally and nationally. In early 2016, the national board of Parisada issued a formal statement declaring the sacredness around the Benoa site and rejected the reclamation. Coming from the highest level of Hindu council in Indonesia, Parisada’s statement had political influences at the national level. that claim has a because it claimed to represent the whole Hindu community in Indonesia.

Parisada became the pioneer in reconstructed again the understanding of sacred place and other theological conceptions that used by other movements to reject the reclamation. Beginning of 2013, Parisada developed a theological argument about the reclamation of Benoa Bay based on principles found in Tri Hita Karana and Sad Kertih. The central text for the Hindu-Bali communities, Tri Hita Karana talks about living in perfect harmony the three elements of human life: God, then other human beings and the environment. Another theological conception that has been used by the Parisada to reject the reclamation, Sad Kertih also talks about living in harmony with the universe. Sad Kertih specifically mentions the ocean, the forests, the lakes and also other human. While the Tri Hita Karana coming from general Hindu concepts found in the Vedas, Sad Kertih draws on the tradition of local Hindu-Bali traditions. Veda They have been used previously to support other political interests, including supporting the 1969 Rencana Pembangunan Lima Tahun (five-year development plan).

Even though Hindus are the majority in Bali, especially in Benoa Bay area, Bali is not homogeneous. There are some other communities that aren’t Hindu. Therefore, according to the author, the claimed of sacredness in Benoa Bay should not be the ultimate reason to reject the reclamation but the society need their own logic and perspectives to perceive this problem.

There are some characteristics of religion revival in the case of Teluk Benoa Bay if we compare to Thoft’s characteristics of religion revival. First, it refer to the participation of religious communities, which is this case are represent by the Parisada and other religious communities that live around Benoa Bay. Second, crisis on understanding religion from the secular world. In Indonesia’s context this process happened after the fall of new order, while religion and state being separated and even there was intervention to the religious related things. The third characteristic is the freedom of religious expression which is also begin after the fall of new order. And the last one is the influence of globalization, democracy and modernization.

Partigor argues that the discourse using a theological perspectives in order to reject the proposed reclamation could be an evaluation of John Rawls’s theory about public logic. Rawls argued that any decision made in public should be based in inclusive ideas that canbe accepted by everyone from various backgrounds. In the debates of Benoa Bay reclamation, an exclusive idea was used in public by a religious actor and the public accepted it.

Title: Significances of Theological Argumentation in Rejecting the Proposed Reclamation of Benoa Bay | Author: Partigor Daud Sihombing (CRCS, 2016)

Abstract

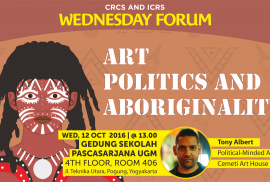

Tony Albert is a politically-minded artist provoked by stereotypical representations of Aboriginal people and the colonial history that attempts to define him, and what Aboriginality is, in the present. Interrogating contemporary legacies of colonialism that have impacted the lives of Aboriginal peoples in his homeland of Australia, he mines popular culture imagery and art historical source material while drawing upon personal and collective histories. His talk will explore Australian politics in relation to his own art practice. Examining the legacy of racial and cultural misrepresentation, particularly of Australia’s Aboriginal people, Albert has developed a universal language that seeks to rewrite historical mistruths and injustice.

Speaker

Tony Albert has spent the majority of his life in Brisbane, but has strong family connections further north to the Girramay and Kuku Yalanji people of the rainforest region of Australia. In 2004 he completed a degree in Visual Arts, majoring in Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art, at Griffith University. His work has been exhibited and collected by major institutions throughout Australia and he is currently artist-in- residence at Cemeti Art House, Yogyakarta.

Abstract

Indonesian Islam connotes a pluralistic form of faith that is open and deeply engages local-specific cultures that concurrently emphasize a rigorous pursuit of social justice and equality for all. Despite the voluminous scholarship on Indonesian Islam, its correlation with Muhammadiyah’s “Islam Berkemajuan” and Nahdhatul Ulama’s “Islam Nusantara”—each having its own vision for a good society—remains woefully unexplained. This paper explores the interplay between Indonesian Islam and the praxis of democracy within the historical context of overcoming an apparent inferiority complex suffered by some segments of the Muslim community. The authors argue that as much as Indonesian Islam may have proven itself to be distinct from ‘the other Islams’, commonly found in its birthplace in the Middle East, there is still much to be desired for in terms of how to confidently overcome the historical baggage as a once colonized people. Using Said and Foucault’s analytical frameworks, the paper argues for a less humble attitude toward the propagation of Indonesian Islam to the outside world, given the protracted period of instability in the Middle East, ongoing terror attacks in different parts of the world and the politics surrounding Islamophobia.

Speaker

Breanna Bradley is an undergraduate student at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service located in Washington, District of Columbia, USA. Bradley’s studies focus on the relationship between culture and politics in Southeast Asia. She is currently a research assistant at the Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS), a Ph.D. program in Inter-Religious Studies located at Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She has previously held positions as an undergraduate research fellow at Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs and as a program coordinator for Georgetown University’s D.C. School’s Project, a program aimed to provide English language access for the immigrant community of the Washington DC area. She is interested in the role that Indonesian Islam plays in Indonesian culture and politics and is currently assisting with research surrounding the Tabot festival, a festival with its roots in Shia Islam celebrated by a majority Sunni community every year in Bengkulu, Sumatra.

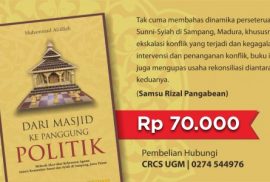

Judul

Judul

Dari Masjid ke Panggung Politik, Melacak Akar-akar Kekerasan Agama Antara Komunitas Sunni dan Syiah di Sampang, Jawa Timur

Penulis

Muhammad Afdillah

Penerbit

CRCS 2016

ISBN

978-602-72686-6-1

Harga

Rp 70.000,-

Beberapa aspek politik dan kekerasan Sunni-Syiah di Sampang dibahas di dalam buku ini. Salah satu di antaranya penyebab konflik antara komunitas Sunni dan Syiah di Sampang. Selain itu, buku ini membahas dinamika konflik Sunni-Syiah, khususnya eskalasi konflik yang terjadi seiring dengan berjalannya waktu dan kegagalan intervensi dan penanganan terhadap konflik tersebut. Buku ini juga membahas usaha – usaha rekonsiliasi kedua komunitas, khususnya setelah kekerasan terbuka yang terjadi di Bulan Desember 2011 dan Agustus 2012.

(Samsu Rizal Panggabean, Pengajar di Magister Perdamaian dan Resolusi Konflik di Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Universitas Gadjah Mada).

__________________________

Bagi yang tertarik, bisa menghubungi:

Divisi Marketing CRCS UGM

Gedung Lengkung Lantai 3

Sekolah Pascasarjana Universitas Gadjah Mada

Jl. Teknika Utara, Pogung, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 55281

Telephone/Fax : + 62-274-544976

Abstract

Rumors about head-hunting and construction sacrifices have been recorded in Southeast Asia since the beginning of 20th century. My focus is on the present-day form of these rumors on the island Sumba, Eastern Indonesia. First directed especially at the Dutch colonizers, stories about foreigners seeking for body parts have continually absorbed new features. In 1990’s, they focussed on new technologies that were imagined as electronic phantasms. Nowadays they target tourists and immigrants as well as people deviating from social norms. Following Jean-Nöel Kapferer, who defined rumors as one of the defense mechanisms by which members of communities try to preserve their old ways, I interpret Sumbanese rumors as a way for Sumbanese to define themselves in opposition to outside forces and as a tool for maintaining norms in society.

Speaker

Adriana Kábová earned her Master’s degree in Ethnology from the Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic. She is a PhD candidate in Anthropology, also at the Charles University in Prague, and is currently on an internship in the Pusat Studi Pariwisata at UGM. Her research interests include tourism and contemporary legends in Southeast Asia.

Daud Sihombing | CRCS | Article

Wilfred C. Smith in his book “The Meaning and the End of Religion,” defines reification as mentally making religion into a thing, gradually coming to conceive of religion as an objective systematic entity. In this process, religions are standardized and institutionalized. For instance, there were no “Hindus” who defined their practice as Hinduism until the term Hindu was established by Muslims and later British colonizers who invaded and sought to know and rule India. It was Muslims and Westerners with their concepts of religion who constructed or reified Hinduism.

Wilfred C. Smith in his book “The Meaning and the End of Religion,” defines reification as mentally making religion into a thing, gradually coming to conceive of religion as an objective systematic entity. In this process, religions are standardized and institutionalized. For instance, there were no “Hindus” who defined their practice as Hinduism until the term Hindu was established by Muslims and later British colonizers who invaded and sought to know and rule India. It was Muslims and Westerners with their concepts of religion who constructed or reified Hinduism.

Based on Smith’s insight, I am going to conduct an art exhibition which I call REIFICATION. In this exhibition I create an imaginary government institution named the Department of Certification. In my exhibition, this fictional governmental institution issues certificates for beliefs that fulfill the requirements to be recognized as a religion. My goals by conducting this exhibition are framing the religious discourse I learned in the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS), Universitas Gadjah Mada, in a different medium and offering new perspectives for seeing religious life in Indonesia.

This project can be considered a reflection of the past or the prediction for the future. What I mean by the reflection of the past is that I am going to visualize the unseen practice of standardizing the concept of religion and recognizing particular religions that happen in the past, especially in Indonesia. In predicting the future, I argue that this governmental institution can exist in Indonesia when the Bill of Rights protecting all religious people has been finalized.

This method of manipulating, imitating, pretending, or camouflaging in order to document an alternate reality has been used effectively by both Indonesian and foreign artists. An Indonesian artist, Agan Harahap created a photo series entitled The Reminiscence Wall, a compilation of “fictional novels” based on history that combines various realities of what happened in the past. Another example is Robert Zhao Renhui, a Singaporean multi-disciplinary artist. He constructs and layers each of his subjects with narratives, interweaving the real and the fictional. He focuses on the relation between humans and the natural world. Both Agan and Robert Zhao creates new “facts”based on their own fictional narratives.

This exhibition will be held in:

LIR Space, Yogyakarta, from September 3rd to 17th, 2016.

Open 12 pm – 20 pm, Closed on Monday.

It will be curated by Mira Asriningtyas as part of the ongoing Exhibition Laboratory project organized by Lir Space.

Robina Saha | CRCS | Article

Robina Saha is a Shansi Fellow to Indonesia. She taught english at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University Yogyakarta from August 2014 – to June 2016.

Robina Saha is a Shansi Fellow to Indonesia. She taught english at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University Yogyakarta from August 2014 – to June 2016.

I first visited the city of Banda Aceh in the spring of 2009. As I stepped out of the airport and drove into town, I was greeted by a quiet Indonesian city framed by a gorgeous vista of mountains to the south, glittering coastline in the north, and tranquil rice paddies in between. Smooth, wide roads and fresh-faced buildings were the most telling signs of the city’s destruction at the hands of the 2004 tsunami and the investment that flowed into Aceh in its wake. The hotel where I stayed displayed photos of boats that had crashed into houses miles away from shore, some of which remain in situ today as memorials and tourist attractions. But it was hard to map these images of debris and desolation onto the clean, quiet little space I traversed between the hotel and the public school where I taught for a week.

At sixteen, I knew little about Aceh apart from its destructive encounter with the tsunami. Although I was born in Indonesia and lived in Jakarta for the first six years of my life, Aceh was geographically, culturally and politically as far removed as any other country. Until 2005, the region had been embroiled in a bloody conflict between the Indonesian military and the separatist Free Aceh Movement; at the time, travel to Aceh was rare and required special permits. Growing up in metropolitan cities where headscarves were rare and the vast majority of Indonesians I knew were from the island of Java, Aceh was something we only heard about on the news in relation to sharia law and ongoing violence. Looking back, I went to Aceh with an image not dissimilar to the one most Americans have of the Middle East, or Indians of Kashmir: Islamic fundamentalism and destruction.

Upon actually arriving in Banda Aceh, I felt a little foolish for being surprised, half-expecting to be accosted by the sharia police at every corner. While all the Indonesian women wore jilbabs (headscarves), I was never made to feel uncomfortable for leaving my frizzy nest of hair exposed. If anything, in a city more accustomed to Western NGO-workers, my face and arms were of interest mainly in order to determine whether I was possibly related to any Bollywood stars (specifically: Kajol; answer: I wish). Like many cities in Indonesia, there are mosques on every street, and I enjoyed seeing the variety of styles and sizes, from simple neighbourhood masjids to the toweringly beautiful Baiturrahman Grand Mosque. At prayer time, the entire city, warungs and all, would shut down, often leaving us to order room service nasi goreng or head to the lone Pizza Hut where we would sip on bottles of Coca Cola and wait it out.

In other words, my prevailing impression of Banda Aceh was of a quiet, conservative, and surprisingly lovely Muslim city populated by Indonesians just as friendly, curious and warmly hospitable as any other I’ve met. Later, upon reflection, I realised that as a visiting foreigner it was easy to glance over the strict policing of moral codes when I wasn’t the target. I never crossed the sharia police in their khaki uniforms, prowling the streets in pick-up trucks and lying in wait at roadblocks in search of unmarried Indonesian couples and uncovered Muslim women. After reading more about the region’s turbulent history, I came to appreciate that I had barely scratched at the surface layer of a city grappling with the process of constructing a contemporary social and political Islamic identity. The after-effects of a natural disaster popularly viewed as a punishment from Allah for decades of civil war had etched themselves far more deeply in the Acehnese psyche than I could have shallowly perceived.

Although I was born in, come from, and grew up in countries with significant Muslim populations, this was in many ways my first conscious confrontation with the blurred convergences between the Islam I saw in the media and what I observed on the ground. At times it can feel like staring at a double-exposure, trying to figure out where one image ends and the other begins. Looking back, although I wouldn’t have said it at the time, many of the decisions I made over the next six years—learning Arabic, studying Islamic culture and politics, writing my senior thesis on the post-9/11 display of Islamic art in Western museums, and ultimately coming back to Indonesia as a Shansi Fellow—could potentially be traced back to this first encounter with contemporary Islam and the questions it sparked in my mind about the representations and realities of Muslims around the world.

When I was first offered the Jogja fellowship in November 2013, I was deep in the process of writing my senior thesis, which was in part a critique of the Islamic art field for its exclusion of most non-Middle Eastern Islamic cultures. Having grown out of European colonial paradigms of Islam, the Middle East and Asia, what we call “Islamic art” is largely limited to the art and architecture of the Arabian Peninsula, Central Asia, Iran, Turkey and India. Islam first arrived in Southeast Asia through trade as early as the 12th century, and today the region makes up a quarter of the world’s Muslim population. It’s also one of many areas that are conspicuously absent from introductory textbooks, museum displays and courses of Islamic art. Specifically in the case of Indonesia, this too can be traced back to the impact of Dutch colonial scholarship, which focused on the archipelago’s Hindu and Buddhist heritage at the expense of its contemporary Islamic culture—partly as a way to delegitimize local Islamic resistance groups. Over time it became an accepted truth that Islamic cultures outside of the European-defined Orient were simply a corruption of the “real” Islam.

In a post-9/11 context where the international image of Islam is largely informed by the puritanical Wahhabism propagated by Saudi Arabia and the fundamentalist extremism carried out by ISIS, I argued in my thesis that the inclusion and visibility of Islamic culture from traditionally peripheral regions like Southeast Asia in displays and discussions of Islamic culture would help challenge the common misconception of a singular Islam located solely in the Middle East. At 200 million and counting, Indonesia has the single largest population of Muslims in the world, and yet most people would struggle to find it on a map. The Islamic culture that developed and spread here in the 15th and 16th centuries is certainly different and more syncretic in character due to its intermixing with pre-existing Hindu and Buddhist religions of the time. But to me this speaks more to the diversity of Islam across the world than the predominance of a single, “original” interpretation that has come to dictate the mainstream international discourse.

Jogja, as the heartland of Javanese culture and the seat of the last major Muslim kingdom in Java, with a majority-Muslim population and a thriving contemporary art scene, presented what seemed like a perfect opportunity to test the ideas I had put forward in my thesis. Despite having grown up in Southeast Asia, I still knew shamefully little about its history of Islamic culture, and I was about to spend two years in the heart of it all. This time, I wanted to come prepared with questions that would frame my thoughts and conversations here.

In the last 15 years, it seems that Indonesia has undergone a sharp Islamic revival, particularly among the younger middle-class generation. When my family left in 1999, it was still relatively rare to see women wearing jilbabs; indeed, for decades, the government had actively discouraged it as a threat to the pluralism that is enshrined in Indonesia’s political doctrine. These days, it’s uncommon for Muslim women not to wear one. Everyone I spoke to in the weeks leading up to my departure, from professors to old family friends, warned of increasing Muslim conservatism, even in a relatively liberal university town like Jogja. I was sharply reminded of my pre-Aceh expectations and the lessons I had learned since, but nonetheless packed a few scarves just in case.

The truth, as always, is a little more complicated. Islam here is certainly more visible than it has ever been. Schools are increasingly adopting policies that emphasise Islamic religious practices and uniforms, even in public universities. In any of my classes, out of roughly twenty-five students it’s rare to see more than two girls without a jilbab. According to a Muslim feminist activist I met a few months ago, this is a marked change from the Suharto era, when jilbabs were banned on school grounds and students and teachers alike could be expelled for wearing one. Wearing a jilbab in the Suharto days, it seems, became a form of symbolic resistance to the regime.

And yet, for many of the young Muslims I meet in Jogja, overt religious piety seems to function more as a public uniform that marks their identity and allows them to fit in. I still remember meeting my friend Imma at a café late one night, who turned out to be a student at the graduate school where I teach. Dressed in a chic powder-pink blouse, she wore her hair uncovered in a pretty shoulder-length bob. Upon discovering that I worked on the same campus as her, she grinned conspiratorially at me and said, “You probably won’t recognise me at school because I usually wear a jilbab.” When I responded with a confused blink, she laughed, explaining that she views the jilbab as a formal uniform for campus the way we wear blazers and heels to work in the West. As a Muslim woman she exercises her right to choose to cover up without compromising her beliefs. For her and her female Muslim friends, choosing not to wear the jilbab has become the new form of public resistance.

It was easy for me to think of Imma and her friends as an exception to the rule. Yet over the past two years I’ve met so many young Indonesians with their own approaches to the way they practice Islam, ranging from Muslims who cover their hair to those who sport chic haircuts; Muslims who identify as queer, gay and transgender; Muslims who have ringtones reminding them to pray during the day yet still drink alcohol at night. As I’ve come to know these people over extended karaoke sessions and late night café hangouts, it’s become clear that the way they practice their faith also constitutes a rejection of the idea of a single interpretation of Islamic law and culture.

A few months ago, Indonesia attracted international attention when it was featured in a New York Times article that described a film made by Nadhlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest Muslim organisation, which denounces the actions of ISIS and promotes tolerance—or, as the author Joe Cochrane puts it, “a relentless, religious repudiation of the Islamic State and the opening salvo in a global campaign by the world’s largest Muslim group to challenge its ideology head-on.” The film is designed to introduce the world to NU and Islam Nusantara, or Indonesian Islam, as a tolerant and moderate alternative to fundamentalism and Wahhabist orthodoxy, rooted in traditionalist Javanese approaches.

Islam in Indonesia certainly can provide a model for tolerance and pluralism within a global Islamic framework. And like any other religious society, it also has its own tensions and fault lines. In Jogja it’s common for pro-LGBT and feminist events and film screenings to be shut down or cancelled by threats from radical groups like the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) and the Front Jihad Islam (FJI). Many of these communities have been forced underground, and news is most often spread by word of mouth for fear of retaliation. My friends have been threatened and beaten at parties where the police have stood by and watched as FPI thugs lay waste to the venue. Just a few months ago, the city was plastered with anti-LGBT propaganda, and Pondok Pesantren Waria Al Fatah, an Islamic school for transgender Muslims, was forced to shut down amidst waves of extremist-led homophobic rallies.

In discussions about Islam and extremism, I often hear non-Muslim friends, family and colleagues calling upon Muslim communities to reject Islamic fundamentalism. That it is the responsibility of the moderate Muslims of the world to provide proof that they exist, to drown out the noise of radicalism that has dominated the airwaves. I’ve always felt uncomfortable with this idea because it ignores the fact that Muslims themselves are already the single largest victim of fundamentalist violence and oppression. For every beating, cancelled event and anti-progressive demonstration, there are Indonesian Muslims fighting back on the ground and on social media, rejecting the actions of these groups as un-Islamic—a word that continues to shift its meaning every time it is used.

Last December, I went back to Aceh to visit the Shansi fellows there. In many ways it was like being there for the first time; there was so much more to see and learn about beyond my limited initial experience. This time, armed with a motorbike, friends on the ground, and the ability to speak Indonesian again, I could finally start to fill in the outlines sketched in my mind six years ago with colour and complexity. One thing I didn’t notice the first time was the absence of cinemas, which were banned across Aceh under post-tsunami sharia law; men and women are not allowed to sit together in dark spaces, and foreign films are considered too promiscuous for Muslim audiences. The nearest movie theatre is in Medan, a fourteen-hour bus ride south.

Yet Acehnese film culture is far from dying. One night while we were staying in Banda Aceh, my co-fellow Leila was asked to judge a few short documentaries made by local filmmakers. We drove to a small studio tucked away on in a quiet street corner, where a group of young Muslim men greeted us with salak fruit and bottles of water. The corridor outside the screening room was lined with posters of short films and documentaries that, it turned out, had been organised and often produced by the same group. They provide resources for young filmmakers, run workshops, and organise screenings and programs like the Aceh Film Festival, which features short films and documentaries from Aceh, Indonesia and abroad. When I asked about the ban on cinemas, they expressed frustration at being unable to screen their films in a local theatre, but it hasn’t deterred them. If anything, the indie film scene has flourished in the wake of conservatism both in quantity and quality; Acehnese films are increasingly gaining recognition at national and international festivals.

In the six years I’ve spent studying Islamic culture and politics, I’ve learned that every one of these seeming contradictions constitutes a small part of the fascinating picture of the global religious, political and cultural phenomenon of Islam. When we allow the rich variety of opinions, practices and traditions across Islam’s broad geographic spread to be reduced to a single interpretation, we lose the shades of variation between depths and shallows, beauty and ugliness, tolerance and extremism. These last few months in particular—revisiting Aceh, travelling to Kashmir for the first time, and witnessing Jogja struggle visibly with surges of intolerance—have served to reinforce the importance of experiencing the broad spectrum of Islam firsthand. And the Islam I encounter in Jogja is as different from Acehnese Islam as it is from Kashmiri Islam, or Saudi Arabian Islam, or Iranian Islam.

I came to Indonesia with so many questions about Islam, and I will almost certainly leave it with just as many. But living here, witnessing the different facets of Islam Nusantara everyday has forced me to continuously confront my conceptions of Islam in a way that simply studying it from afar never could. Learning to recognise, understand and embrace these distinctions, contradictions and complexities has been a defining theme not only of my fellowship, but my entire understanding of contemporary Islam. Wherever my life takes me after Shansi, I hope I can continue to encounter Islam in all its various, beautiful, troubling, complex forms.

This article also published in http://shansi.org/

Farihatul Qamariyah | CRCS | News

Over the last several years, students from the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS) Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, have been participating in the annual Graduate Student Fellowship Program hosted by Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. Started in 2005, this program offers graduate students working in the Asian topics related to the Humanities and Social Sciences from different universities and countries around Southeast Asia to spend two months based at the Asia Research Institute where they are mentored by ARI researchers and collaborate with other fellows from around the region as well as utilizing the wide range of resources in the libraries of NUS and the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute). This fellowship culminates with a conference for the fellows as well as other students from the region to present their research at the end of the program. During the program, the fellow students are able to participate in any seminars held in ARI and other institutions based in NUS. ARI also arranges a professional mentor, either an NUS lecturer or ARI scholar, for each of the students to offer personal consultation and advise according to each student’s research interest and topic. Since the primary goal of this program is to produce an academic paper that will be presented in the Graduate Forum, ARI organizes a course in Academic English Writing and Communication. These kind of activities effectively support the fellow students to improve their academic expertise as well as enrich the international experiences through the daily interaction and discussion. This year, ARI invited fellows from more diverse backgrounds compared with the previous year. There are fellows from the following countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Philippines, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, China, India and USA.

Over the last several years, students from the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS) Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, have been participating in the annual Graduate Student Fellowship Program hosted by Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. Started in 2005, this program offers graduate students working in the Asian topics related to the Humanities and Social Sciences from different universities and countries around Southeast Asia to spend two months based at the Asia Research Institute where they are mentored by ARI researchers and collaborate with other fellows from around the region as well as utilizing the wide range of resources in the libraries of NUS and the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute). This fellowship culminates with a conference for the fellows as well as other students from the region to present their research at the end of the program. During the program, the fellow students are able to participate in any seminars held in ARI and other institutions based in NUS. ARI also arranges a professional mentor, either an NUS lecturer or ARI scholar, for each of the students to offer personal consultation and advise according to each student’s research interest and topic. Since the primary goal of this program is to produce an academic paper that will be presented in the Graduate Forum, ARI organizes a course in Academic English Writing and Communication. These kind of activities effectively support the fellow students to improve their academic expertise as well as enrich the international experiences through the daily interaction and discussion. This year, ARI invited fellows from more diverse backgrounds compared with the previous year. There are fellows from the following countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Philippines, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, China, India and USA.

This year, five students of CRCS are invited to join the Asian Graduate Student Fellowship from May 22nd – July 15th 2016, two from the 2013 batch (Fredy Torang and Yoga Khoiri Ali) and three from the 2014 batch (Abdul Mujib, Aziz Anwar Fachrudin, and Farihatul Qamariyah). Two more (Partigor Daud Sihombing and Subandri Simbolon) have been selected as presenters at the Graduate Forum that will be held in July 2016. The fellows from CRCS bring research projects connected to their thesis projects that are especially related to ARI’s topic clusters including Cultural Studies in Asia and Religion and Globalization. Mujib’s project is entitled “The Relevant of Interreligious Relations in Shaping of Experience in Diversity and Pluralist Attitude” and examines the case of one multi – religious village located in Yogyakarta. Aziz’s research on ISIS discourse is titled “Indonesian Islamist Ideological Responses to the Islamic State”. Qamariyah’s research focuses on the issues of gender, religion and business and is entitled “Women, Islam, and Economic Activity by Examining the Religious Ethics of Muslim Business Women in Indonesia”. Fredy’s topic of research is “Faith Based Organization in Humanitarian Diplomacy: A Case Study of the Jesuit Refugee in Yogyakarta” and Yoga’s research examines “The Spirituality of Rain Water from the South East Slope of Mountain Merapi”. These various topics are expected to contribute significantly to the Asia Research Institute’s interests.

The participation of CRCS’ students in this fellowship for over ten years is a demonstration of the center’s academic track record on the international academic stage. “It is almost a tradition that CRCS UGM students have almost always been in the list of Asian Graduate Student Fellowships ARI – NUS recipient since the first batch”, said Ida Fitri Astuti (Batch 2013) who participated in this program last year. She also testified to the great benefit of this graduate fellowship program for her academic improvement and international network based on her own experiences. “This program is a kind of salad bowl which gathers Asian students to meet up each other, learn and bound together by “academic dressing” produced by the excellent staff and scholars of ARI – NUS.” This testimony was also confirmed by another CRCS’ student who is now experiencing the turn. “This place is like an academic heaven, a lot of literatures and academic sources are available here. ARI NUS provides us a great facility and possibility to explore and utilize the academic prosperity by the services. It is an extremely exciting!” said Fredi Torang through his first excitement living in the new environment.

Based on the documentation, about twenty seven students of CRCS have been Asian Graduate Student Fellows, starting with Ali Burhan in 2006, the program’s second year. Since then,CRCS participants have been Chandra Utama and Maufur in 2007; Akhmad Siddiq, Muhammad Endy Saputro and Ferry Muhammadsyah Siregar in 2008; Amanah Nurish and Saipul Hamdi in 2009; and Ruby Emy Astuti and Jimmy Immanuel Marcos in 2010. 2011 was the previous record year with four students: Mega Hidayati, Yudith Listiandri, Muhammad Rokib and Dian Maya Safitri. Only one student, Darwin Darmawan, was chosen in 2012. Anwar Masduki and I Made Arsana Dwiputra participated in 2013. Two students, Ida Fitri Astuti and Sulfia Lilin Nurindah Sari, were able to attend in 2015, with another, Hary Widyantoro, joining as a presenter in the Graduate Forum. Thus, when the five fellows are joined by the two presenters, this year of 2016 has the highest number of CRCS students selected as Asian Graduate Student Fellows and Graduate Forum presenters: seven. This is our challenge to the batches that follow us.

The Kosmopolis Platform/Dept. of Globalization and Dialogue Studies of the University of Humanistic Studies (the Netherlands), in cooperation with HIVOS (Humanist Institute for Cooperation with Developing Countries), The Asia Foundation, Azim Premji University, (India), PUSAD-Paramadina and The Centre for Religious and Cross-Cultural Studies of Gadjah Mada University (Indonesia) and the Institute for Reconciliation and Social Justice of the University of the Free State (South Africa) welcomes applicants for the 2016 International Summer School on Pluralism, Development and Social Change.

Asep A.S | CRCS | News

Gunungkidul ditengarai sebagai kabupaten dengan tingkat intoleransi paling tinggi di Yogyakarta. Setidaknya, itulah salah satu hal yang terungkap dalam acara launching buku sekaligus diskusi mengenai laporan advokasi kebebasan beragama bertajuk “Yogyakarta City of (In)tolerance?,” Senin, 2 Mei 2016, di Sekolah Pascasarjana UGM. Informasi mengenai masih tingginya angka kasus intoleransi di Kabupaten ini diketahui setelah Aliansi Nasional Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (ANBTI) melakukan pendokumentasian atas kasus-kasus pelanggaran kebebasan beragama dan berkepercayaan di kabupaten tersebut yang terjadi selama kurun waktu 2011 hingga 2015. Di dalam laporannya, ANBTI mengkategorikan beragam kasus pelanggaran tersebut ke dalam empat kategori, yakni (1) pelanggaran oleh negara atas keinginan mengontrol ekspresi keagamaan; (2) pelanggaran yang terjadi akibat perilaku intoleran yang dilakukan oleh negara dan non-negara; (3) pelanggaran yang terjadi akibat kegagalan negara di dalam mengatasi baik diskriminasi ataupun pelanggaran sosial atas kelompok-kelompok agama tertentu; serta (4) pelanggaran yang terjadi karena menerapkan kebijakan tertentu yang merugikan agama-agama minoritas.

Gunungkidul ditengarai sebagai kabupaten dengan tingkat intoleransi paling tinggi di Yogyakarta. Setidaknya, itulah salah satu hal yang terungkap dalam acara launching buku sekaligus diskusi mengenai laporan advokasi kebebasan beragama bertajuk “Yogyakarta City of (In)tolerance?,” Senin, 2 Mei 2016, di Sekolah Pascasarjana UGM. Informasi mengenai masih tingginya angka kasus intoleransi di Kabupaten ini diketahui setelah Aliansi Nasional Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (ANBTI) melakukan pendokumentasian atas kasus-kasus pelanggaran kebebasan beragama dan berkepercayaan di kabupaten tersebut yang terjadi selama kurun waktu 2011 hingga 2015. Di dalam laporannya, ANBTI mengkategorikan beragam kasus pelanggaran tersebut ke dalam empat kategori, yakni (1) pelanggaran oleh negara atas keinginan mengontrol ekspresi keagamaan; (2) pelanggaran yang terjadi akibat perilaku intoleran yang dilakukan oleh negara dan non-negara; (3) pelanggaran yang terjadi akibat kegagalan negara di dalam mengatasi baik diskriminasi ataupun pelanggaran sosial atas kelompok-kelompok agama tertentu; serta (4) pelanggaran yang terjadi karena menerapkan kebijakan tertentu yang merugikan agama-agama minoritas.

Pada diskusi yang dihelat oleh Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya atau CRCS melaui program Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragaman (SPK) dan ANBTI ini pembicara dari ANBTI, Agnes Dwi Rusjiati, menyebutkan beberapa contoh peristiwa pelanggaran yang terjadi di Gunungkidul, seperti pengusiran Pendeta Agustinus, penutupan Gereja Pantekosta di Indonesia (GpdI) Semanu dan Gereja Pantekosta di Indonesia (GpdI) Playen yang telah memiliki IMB, penyerangan dan penutupan atas Gereja Kemah Injili Indonesia (GKII) Widoro, penolakan acara perayaan Paskah Adiyuswo Gereja Kristen Jawa (GKJ) Gunugkidul yang disertai penganiayaan terhadap aktivis lintas iman, serta penolakan pendirian Gua Maria Wahyu Ibuku di wilayah Giriwening. Memang, belakangan ini Yogyakarta yang kerap disebut-sebut sebagai City of Tolerance sedang dirundung banyak problema dalam hal toleransi, baik antar maupun antara umat beragama maupun antar kelompok ormas. Terbukti, sebagaimana disebutkan oleh Agnes, kasus-kasus intoleransi seperti penyerangan dan pembubaran diskusi, perusakan situs makam, penyerangan terhadap doa rosario, intimidasi terhadap kelompok tertentu seperti Syiah dan LGBT, penghentian ibadah di gereja, serta usaha penutupan rumah ibadah kerap terjadi di provinsi yang berjuluk kota budaya ini.

Di dalam kesempatan tersebut, Agnes juga memaparkan bahwa peristiwa pelanggaran kebebasan beragama yang terjadi di kerap kali seputar persoalan penolakan pelaksanaan ibadah maupun keberadaan rumah ibadah umat Kristen, baik yang telah dibangun maupun masih dalam proses pembangunan. Selain itu, ia juga mengeluhkan bahwa setiap pertemuan yang difasilitasi oleh Pemda mengenai persoalan rumah ibadah ini akan berujung pada penghentian rumah ibadah, selain juga proses yang berlarut-larut dan kurangnya peran aktif pemerintah dalam menangani kasus-kasus semacam ini. Kerap kali, pemerintah baru bertindak setelah ada inisiasi dari warga. Isu kristenisasi, pemurtadan, dan adanya penolakan dari masyarakat muslim yang kemudian mendesak pemerintah daerah untuk melakukan penghentian rumah ibadah menjadi pola khas dalam kasus kebebasan beragama dan berkepercayaan yang terjadi di ini.

Senada dengan Agnes, Kristiana Riyadi—pembicara dari Forum Kerukunan Umat Beragama (FKUB)—menyebutkan bahwa peran FKUB di dalam membangun kerukunan dan toleransi antar umat beragama masihlah sangat minim. Bahkan, FKUB sendiri secara internal masihlah menyisakan konflik, hal ini sangat berbeda dengan kondisi sebelum adanya FKUB yang merupakan keputusan menteri, di mana kala itu forum komunikasi antar agama masih bernama Forum Lintas Iman. Hal ini terjadi, menurut Kristiana, disebabkan oleh penekanan pada proporsionalitas yang diatur dalam SK menteri tahun 2006. Tentu saja, Islam yang mayoritas akan memiliki jumlah wakil yang lebih banyak di dalam FKUB. Sebagai contoh, pimpinan FKUB yang berjumlah lima orang dengan asumsi merupakan wakil dari setiap agama yang diakui oleh negara, tiga di antaranya diduduki oleh wakil dari umat Islam. Sehingga, dengan pertimbangan tertentu, akhirnya khusus FKUB , sesuai dengan keputusan Bupati , memiliki tujuh orang pimpinan agar dapat mengakomodir semua agama.

Persoalan lain yang dihadapi oleh FKUB adalah soal menyerap aspirasi. FKUB semestinya menyerap semua aspirasi masyarakat dan umat beragama. Namun, proses ini menjadi bumerang tersendiri bagi tujuan didirikannya FKUB saat harus berhadapan dengan aspirasi dari kelompok ormas intoleran yang mau tidak mau harus diserap juga. Selain itu, keterpusatan keputusan pada ketua menjadi persoalan tersendiri yang tak dapat dihindari. Sebab, hal ini kerap kali tidak mencerminkan keterwakilan umat beragama yang minoritas. Belum lagi persoalan pengambilan beberapa keputusan terkait persoalan keagamaan ini tidak sepenuhnya berada dalam lingkup FKUB, melainkan pada rapat Muspida, di mana FKUB hanya diwakili oleh satu orang saja, yakni ketua FKUB. Tak heran jika keputusan-keputusan yang dihasilkan kerap kali kontraproduktif dengan visi dan misi didirikannya FKUB itu sendiri. Persoalan lainnya, misalnya, sosialisasi perbedaan peraturan pendirian rumah ibadah sebelum 2006. Sosialisasi mengenai hal ini hampir dapat dikatakan tidak dilakukan. Sehingga masyarakat menganggap peraturan mengenai pembangunan rumah ibadah setelah 2006 bersifat general, sehingga kerap kali terjadi konflik di lapangan karena adanya ketidakpahaman ini. Biasanya kasus perizinan keberadaan rumah ibadah lama yang muncul sebagai akibatnya. Padahal perizinan rumah ibadah yang telah dibangun sebelum tahun 2006 berbeda dengan perizinan rumah ibadah yang dibangun setelah tahun tersebut.

Mengenai persoalan penolakan rumah ibadah ini, pembicara lainnya yang merupakan alumni SPK, Pendeta Stefanus Iwan Listyanto, menyebutkan bahwa terjadinya hal tersebut juga disebabkan oleh adanya persoalan internal dalam golongan agama tertentu. Tak dapat dipungkiri, menurut pendeta dari Semanu ini, adanya persaingan antar gereja membuat umat Kristen pasif saat ada gereja di luar golongannya yang dipersoalkan keberadaannya oleh umat lain. Hal ini menjadi gejala global yang terjadi sehingga kelompok Kristen yang sedang menghadapi masalah dengan rumah ibadahnya kerap harus berjuang sendiri tanpa adanya bantuan dari sesama pemeluk Kristen lainnya. Menurutnya, belum adanya kesadaran mengenai perspektif HAM dan adanya persaingan antar gereja juga memiliki sumbangsih yang cukup besar terhadap tindakan pelanggaran kebebasan beragama dan penyelesaian konflik. Hal ini menandakan masih adanya persoalan di antara umat beragama secara internal. Dengan nada bercanda dan sindiran, ia berkata bahwa mungkin saja ada golongan seagama yang sorak sorai saat sebuah rumah ibadah ditutup atau dipermasalahkan. Karenanya, ia menekankan pentingnya membangun jejaring baik antara maupun antar umat beragama. Dengan berjejaring, menurutnya, seseorang atau kelompok bisa saling bantu melengkapi data pendokumentasian jika terjadi persoalan yang mungkin akan memudahkan proses penyelesaian masalah. Selain itu, memiliki sudut pandang dari pihak korban juga penting untuk membangun empati, agar persaingan itu dapat tetap berjalan secara sehat.

Sedangkan pembicara terakhir, M. Iqbal Ahnaf dari CRCS, menyebutkan bahwa maraknya tindakan intoleransi yang terjadi di Yogyakarta akhir-akhir ini disebabkan oleh banyak faktor. Namun secara ringkas, Iqbal mengerucutkannya ke dalam tiga faktor yang saling terkait dan berinteraksi satu sama lain, yaitu (1) krisis keistimewaan; (2) industrialisasi; dan (3) penebalan identitas. Walaupun masih berupa hipotesis, menurut Iqbal, namun gejala yang menunjukkan ke arah tersebut cukup jelas adanya. “Saya kira, ini sangat terkait dengan pemegang otoritas tertinggi di Jogjakarta. Saya kira kita ingat belum lama ini RUU keistimewaan Jogjakarta mulai mengusik otoritas yang paling mapan di Jogjakarta.” Ungkapnya mengawali penjelasan mengenai persoalan krisis keistimewaan ini. Menurut Iqbal, perubahan peraturan di tampuk pimpinan Yogyakarta ini mencerminkan proses perubahan sosial yang sedang berlangsung. Hal ini kemudian memicu krisis otoritas keistimewaan yang meniscayakan kebutuhan akan kekuatan basis sumber daya di Yogyakarta. Hal ini bertujuan untuk mempertahankan citra keistimewaan itu. Oleh sebab itu kebutuhan akan sumber daya ini kemudian melibatkan perkembangan industrialisasi sebagai salah satu usaha mendapatkan suplai sumber daya.

Menurut Iqbal, pembangunan hotel yang kian marak serta bentuk pembangunan dan industrialisasi lainnya kemungkinan dilakukan untuk memapankan basis-basis sumber daya itu. Konsekuensi dari adanya industrialisasi ini adalah sekuritisasi. Sebab, para investor maupun pengusaha tentu membutuhkan stabilitas keamanan yang cukup untuk menjalankan bisnisnya itu. Karena itu diperlukan kekuatan-kekuatan yang bisa mempertahankan dan mendukung keamanan tersebut. Di bagian inilah kemudian perubahan sosial yang terjadi di masyarakat yang melaju pada arah penebalan identitas dan kian rigidnya batas-batas sosial, baik berlandaskan agama maupun etnik, bertemu dengan realitas kebutuhan akan sekuritisasi ini. Sehingga, tak heran jika kemudian aspek skuritisasi ini diambil alih oleh kelompok-kelompok atau kekuatan-kekuatan yang bergerak di arena penebalan identitas itu. Hal ini semacam simbiosis mutualisme. Kita dapat memahami dengan mudah bahwa ketika seseorang mengalami krisis, maka ia akan membutuhkan dukungan untuk mengembalikan sumberdaya yang hilang. Sumberdaya itu bisa bersifat ekonomi maupun sosial. Industrialisasi ini dapat diidentifikasi sebagai sumber daya yang bersifat ekonomi, sedangkan dukungan kelompok tertentu itu merupakan sumber daya yang bersifat sosial. Kebutuhan akan dukungan sosial inilah yang kemudian dimanfaatkan oleh kelompok-kelompok tertentu—baik keagamaan maupun etnik—untuk merapat pada otoritas kekuasaan di Yogyakarta. Kontestasi antar kelompok itulah yang terkadang menghadirkan konflik. Pergulatan ketiga hal tersebut itulah yang kemudian meniscayakan hal-hal lainnya semisal institusionalisasi kelompok-kelompok pelaku kekerasan dan semakin lemahnya kekuatan moderat kritis. Institusionalisasi ini merupakan bentuk pemapanan oleh sistem yang ada terhadap kelompok-kelompok tertentu. Sehingga, walaupun minoritas, kelompok-kelompok ini dapat bertahan, eksis, dan dominan. Akibatnya, ada kasus-kasus serupa yang kemudian direspons berbeda, tergantung kelompok mana yang merespons dan apa kepentingannya. Kasus pembangunan hotel atau sampah visual, misalnya, menurut Iqbal, diprotes sedemikian rupa. Namun, saat ada rumah ibadah ditutup, tak banyak orang yang peduli.

Di dalam sesi tanya jawab, terungkap pula beberapa fakta mengenai tindakan intoleran yang ternyata tak hanya didominasi oleh ormas atau kelompok-kelompok tertentu, melainkan pula dilakukan oleh negara. Menurut Agnes, pemerintah pernah melakukan kerja sama dengan ormas intoleran dalam melakukan intimidasi terhadap kelompok tertentu, seperti yang terjadi pada kasus GKII. Selain itu, aparat yang berjaga di lapangan saat terjadi konflik akibat adanya tindakan intoleransi kerap tidak bertindak mencegah tindakan intoleransi yang dilakukan oleh kelompok tertentu itu, mereka justru terkesan hanya menjaga kelompok tertentu itu agar tidak melakukan tindak kekerasan sehingga tidak dapat dikriminalisasikan. Sedangkan perilaku intoleransinya dibiarkan begitu saja. Selain itu, dalam sesi ini juga terungkap bahwa soal tindakan intoleransi terutama dalam hal keberagamaan tidaklah didominasi oleh agama tertentu, melainkan seringnya dilakukan oleh mayoritas terhadap minoritas, baik internal maupun antar agama. Di Atambua misalnya, menurut Agnes, pernah pula terjadi penolakan pembangunan rumah ibadah agama tertentu dari kelompok minoritas yang dilakukan oleh umat agama yang sama yang mayoritas. Atau, dalam kasus Tolikara dan beberapa wilayah di Indonesia Timur, misalnya, tindakan intoleransi kerap pula menimpa kaum muslim yang minoritas, sebagaimana halnya yang terjadi terhadap umat Kristen dan umat lainnya yang tinggal di wilayah mayoritas umat Islam. Sehingga, menurut Iqbal, menjadi penting untuk memperkuat kelompok-kelompok rentan yang ada. Selain itu, penting pula untuk menanamkan sikap toleransi, kesadaran akan HAM, dan menghilangkan kecurigaan di antara para pemeluk agama yang ada. Sebab, sebagaimana disimpulkan oleh moderator pada acara tersebut, Subandri Simbolon, kedamaian tidak hadir bukan hanya sebab bangkitnya kaum intoleran, namun juga sebab diamnya para pecinta perdamaian.

Ali Ja’far | CRCS | Artikel

“Perubahan besar-besaran pada Klenteng-Vihara Buddha terjadi setelah peristiwa 1965, dimana semua yang berhubungan dengan China dilarang berkembang di Indonesia. Nama-nama warung atau orang yang dulunya menggunakan nama China, harus berubah dan memakai nama Indonesia” kata Romo Tjoti Surya di Vihara Buddha kepada mahasiswa CRCS-Advanced Study of Buddhism, yang melakukan kunjungan pada selasa 22 Maret 2016. Beliau menjelaskan juga bahwa pada waktu itu, umat Buddha juga harus mengalami masa sulit karena banyaknya pemeluk Buddha yang berasal dari China.