Yogyakarta telah lama menjadi rumah yang aman bagi berbagai tradisi, keyakinan, dan paham pemikiran yang beragam. Tetapi Daerah Istimewa ini belakangan disorot karena banyaknya aksi vigilantisme yang dilakukan sejumlah kelompok massa baik yang berlatar belakang agama atau politik. Aksi-aksi vigilantisme yang menyasar kelompok-kelompok sosial dan keagamaan minoritas menimbulkan pertanyaan apakah Yogyakarta, yang dikenal sebagai kota pendidikan dan pusat kebudayaan Jawa yang menekankan pada harmoni sosial, sudah berubah menjadi daerah yang intoleran? Laporan ini menunjukkan bahwa vigilantisme terhadap minoritas tidak cukup secara sederhana dipahami sebagai ekspresi konservatisme keagamaan dan intoleransi para pelaku terhadap minoritas, tetapi juga merupakan bagian dari proses perubahan sosial dan struktural yang diantaranya dipengaruhi oleh dinamika seputar status keistimewaan Yogyakarta. Tidak bisa dipungkiri, sektarianisme yang menguat belakangan ikut berpengaruh, tetapi seringkali kekerasan terhadap minoritas lebih tampak sebagai alat mobilisasi kelompok-kelompok kepentingan tertentu untuk mempertahankan basis sosial-politik yang menentukan kendali mereka atas ruang dan sumber daya.

_________________________

Judul: Krisis Keistimewaan: Kekerasan terhadap Minoritas di Yogyakarta

Penulis: Mohammad Iqbal Ahnaf & Hairus Salim

Penerbit: CRCS UGM

ISBN: 978-602-72686-7-8

Tebal: 134 halaman; 15×23 cm

Cetakan Pertama: April 2017

Harga: Rp60.000,00

__________________________

Narahubung untuk mendapatkan buku ini:

Divisi Marketing CRCS UGM

Gedung Lengkung Lantai 3

Sekolah Pascasarjana Lintas Disiplin Universitas Gadjah Mada

Jl. Teknika Utara, Pogung, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 55281

Telephone/Fax: 0274-544976

Atau melalui WA: 082141724150 (Bandri)

Lihat juga buku-buku publikasi CRCS yang lain di sini.

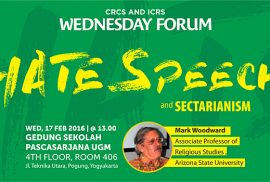

Sectarianism

ABSTRACT

Hate speech is one of the factors contributing to sectarian and ethnic conflict. It typically includes social/psychological processes of dehumanization and demonization that define others as less than human and archetypes of evil. Often others are described as existential threats to the very existence of the speaker’s community. It is used to incite or justify violence, sometimes rising to the level of genocide. It is nearly often entirely inaccurate.

Hate speech is an under theorized mode of contentious discourse. It is easy to recognize and difficult to define precisely. In this paper I located hate speech within a four-point typology of contentious discourse: 1. Dialog concerning religious differences; 2. Unilateral condemnation of the beliefs and practices others; 3. Dehumanization and demonization of others and implicit justification of violence; 4. Explicit provocation of violence. For examples I rely primarily on the violent rhetoric of the Indonesian Islamic Defenders Front.

Dehumanization and demonization are the psychological processes that distinguish between civil discourse and hate speech. Levels 1 and 2 are critiques located within the limits of civil discourse because they do not implicitly or explicitly threaten others. Levels 3 and 4 are hate speech. They make symbolic associations that are inherently threatening.

Some forms of hate speech are universal or nearly so. Among these are the description of others as animals, evil, heretics and/or of engaging in “inappropriate” sexual conduct. Others are culturally or religiously specific. More research is required to understand the semantics of hate speech and how it transcends religious and ethnic boundaries.

There is an inevitable contradiction between defending freedom of speech, as guaranteed by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,and protecting people, usually minorities, from the psychological harm hate speech causes and the risk of physical violence it exposes them to.Legal restrictions do not eliminate hate speech; they only drive in from the public sphere. Most laws restricting hate speech were drafted long before the Internet and social media existed. Now, they are largely ineffective. Countering hate speech requires concerted effort by religious and political leaders and netizens across a range of media, including those used most frequently, including social media, by extremists who promote it. In this presentation I rely on examples from Front Pembela Islam (Islamic Defenders Front/FPI).

SPEAKER

Mark Woodward is Associate Professor of Religious Studies and is also affiliated with the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University. His research focuses on religion-state-society relations and religion and conflict in Southeast Asia. He is author of Islam in Java. Normative Piety and Mysticism in the Sultanate of Yogyakarta, Defenders of Reason in Islam (1989)and Java, Indonesia and Islam (2010) .He has published more than fifty scholarly articles in the US, Europe, Indonesia and Singapore, many co-authored with Southeast Asian scholars. He his currently directing a trans-disciplinary, multi-country project on counter-radical Muslim discourse.