Abstract

Scientists say that we have entered the Anthropocene, the era in which the influence of humankind on the many disasters on our earth is decisive. But ancient societies already understood disasters as a very complex and subtle interaction between the mood of man and the movement of nature. This is what we are reminded of by the Javanese tale Babad Ngalor-Ngidul, the title of which comes from a word we no longer understand: ngalor-ngidul. Composed of two Javanese words– lor for north and kidul for south plus the prefix ng that marks a back and forth movement–, ngalor-ngidul must have originally meant “from north to south and from south to north, in an endless burst of reciprocity and interdependence,” but now only means to talk nonsense. In the tale, the fates of the two villages, one in the south near the sea and one in the north near the volcano, are bound together as the former, destroyed by an earthquake, rebuilds itself, body and soul, while the latter becomes mentally corrupted before being devastated by a volcanic eruption. The tale is told in restore among the survivors the clarity of the “eye of the heart” that allowed the guardian of the volcano to “read” the mother-mountain and it reminds us that we must learn again to listen to the water of the ocean and to the sand of the volcano, the last speakers of a “primal” language that has existed since long before humankind.

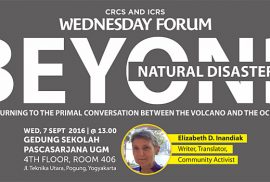

Speaker

Elizabeth D. Inandiak is a writer, translator and community activist. Since the age of nineteen, she has traveled the world as a reporter for various French magazines and radio broadcasters. In 1989, she settled in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She has translated and recreated into French, Indonesian and English the great epic of Java: The Book of Centhini, published in Indonesian by Gramedia (Centhini – Kekasih yang Tersembunyi). Her new book Babad Ngalor Ngidul, (Gramedia) is a tale about the earthquake and the volcanic eruption in Yogyakarta. She is currently working on a book about Muara Jambi together with the young villagers of the site.

Wedforum

Abstract

Corruption is a problem of civilization which, by extension, is a problem of culture. This must be confronted by reviving the cultural values of anti-corruption. Learning from local traditions which combat corruption can be a powerful instrument to fix corrupt tendencies in a state. Strong beliefs in local cultural values can become the base of these efforts. In other words, the culture will create the people, and the people will create the civilization. Presenter try to offer an overview of Mambagi Jambar (Sharing Pieces of Meat) activity as representative of the cultural activities which combat corruption. By basing on ethnographic interviews and analysis of related texts, the presenter will describe this discussion in a systematic matter. The first part introduces global corruption and, furthermore, the issue of corruption in Indonesia. The second part describes the activities of padalan jambar juhut in Toba Batak culture. The last part then discusses these activities and their contributions in an effort to revive anti-corrupt cultural practices.

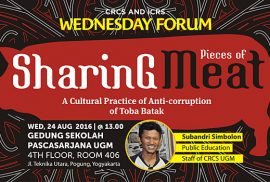

Speaker

Subandri Simbolon is Public education Staf at CRCS-UGM. His research, focused on culture and populer issue, has been published in globethic.net journal. He finished his BA at Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat dan Teologi (STFT) Widya Sasana Malang where he majored in Christian Philosophy. In 2014, he graduated from CRCS-UGM where focuse on Culture and Ecology. In 2014 and 2015, he awarded the first winner for globetthic.net essay competition about “Anti Corruption Ethics and Religiosity (2014) and “Responsible Leadership (2015)“.

Abstract

In this presentation I will explore Robert Bellah’s idea that there were four great axial civilizations which formed the modern world: China, India, Middle Eastern/Abrahamic and Greco-Roman/European. I will suggest that Indonesia occupies a unique role in the modern world because it is not dominated by any one of the 4 axial civilizations but is rather a unique synthesis of all four. Most great nations in the world are dominated by one or two, of these four axial civilizations. My research suggests that most Indonesians hold values and an imagination of social reality which is shaped by all four axial civilizations. In our pluralistic world, Indonesia may hold the key for shaping an Islamic civilization which will bring blessing to the entire world.

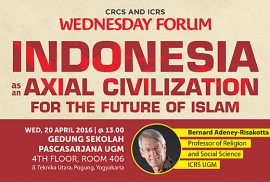

Speaker

Bernard Adeney-Risakotta is Professor of Religion and Social Science and International Representative at the Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS-Yogya), in the Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada. He is currently also teaching at Duta Wacana Christian University and Universitas Muhamadiyah Yogyakarta. Bernie completed his B.A. from University of Wisconsin in Asian Studies and Literature. His second degree, a B.D. (Hons.) is from University of London, specializing in Asian Religions and Ethics. Bernie’s Ph.D. is from the Graduate Theological Union (GTU) in cooperation with University of California, Berkeley, in Religion, Society and International Relations. From 1982 until 1991 he taught at the GTU Berkeley. Bernie has been a Fellow at St. Edmunds College, Cambridge and at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS), Amsterdam. From September 2013 to July 2014 he was on sabbatical leave as a Visiting Fellow at the Institute on Religion and World Affairs at Boston University. He has many publications, including: Just War, Political Realism and Faith (1988), Strange Virtues: Ethics in a Multicultural World (1995), Dealing with Diversity: Religion, Globalization, Violence, Gender and Disasters in Indonesia (2013) and Visions of a Good Society in Southeat Asia (in press, 2016). Email: baryogya@gmail.com

Abstract

The spread of religious millenarianism in the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has raised significant questions about religious movement in those countries. The Baha’i religion provides an important case and relevant context as the Baha’i movement has been paralyzed in its country of origin, Iran, since the beginning of the movement in 1844. To avoid persecution and violence, many Baha’i adherents moved to other regions in Southeast Asia. The Baha’i religion is committed to developing educational skills, economic sustainability, gender empowerment, and social movements. Thus, ASEAN encompasses a dynamic and diverse region that aims to provide social, religious, economic, and cultural security for ASEAN citizens. Minority religions such as the Baha’i community, which at the times are victims of conflict and violence, play an important role in achieving those aims. Conversely, religious violence and conflict may be seen as part of the regional deficit in terms of religious freedom and tolerance. In this context, my study tries to examine religious millenarianism and the future evolution of the ASEAN community. The study investigates the co-existence of the Baha’i community with other religious groups such as Muslim, Christian, and Buddhist in their social, political, and cultural negotiations. As the Baha’i engage on some social and political issues in globalization and embrace liberalism and pluralism in the public space, I argue that this study contributes to scholarship in terms of understanding the fate of religious millenarianism in the future of the ASEAN community.

Speaker

Amanah Nurish Ph.D Cand Researcher of Baha’i studies. She is pursuing doctorate at ICRS UGM-Yogyakarta and working as consultant of USAID team-Washington for assessment program, “Fragility and Conflict”. She wrote book chapters, articles, and journals. Her latest publications: Sufism and Baha’ism: The Crossroads of Religious Movement in Southeast Asia (2016, Equinox publisher, London) Perjumpaan Baha’i Dan Syiah Di Asia Tenggara (2016, Maarif Jurnal, Jakarta) Welcoming Baha’i: New Official Religion In Indonesia (2014, The Jakarta Post) Social Injustice and Problem Of Human Rights In Indonesian Baha’is Community (2012, En Arche Journal, Yogyakarta) etc. She received prestigious awards for her academic works such as King Abdullah Bin Abdulazis’s interfaith center-Vienna, SEASREP-Philippine, ENITS-Thailand, Luce & Ford Foundation-USA, ARI-NUS, etc. With her teamwork, she is currently undertaking a broader anthropological research on “ Religious Millenarianism in ASEAN countries” for publication supported by Arizona State University of America.

Ali Jafar | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

The first CRCS/ICRS Wednesday Forum of 2016 welcomed Risnawati Utami, an activist for the human rights of persons with disabilities who recently played an important role in resolving a case concerning the rights of persons with disabilities in Bali to participate in their religion. . Together with her organization named OHANA (Organisasi Harapan Nusantara), she advocates for the human rights of persons with disabilities for shifting understanding about disabilities to ensure that persons with disabilities are treated as full and equal members of Indonesian society.

In her presentations, Risnawati said that “persons with disabilities constitute about 15% of the world’s population, meaning they are the largest minority in the world and mostly in the developing countries. Why persons with special needs required attention, it is because they are still discriminated against.” In religious model, Utami gave an example about persons with disabilities in Bali. Culturally in Bali, disabilities are understood as resulting from karma or actions done by the parents in their life or as punishment from bad behavior they did. When they have a disabled child, they will put their child in a different place, not in the main house. This happens not only in Bali, but also in many places.

Furthermore, Utami said that in Indonesia generally, the government looks on the person with disabilities as the object of charity, as a person who needs help and as object of development, it is kind of charity model happened. She told about disabled organizations which get a lot of rehabilitation programs, economic assistance, money, etc. ‘Can we see normality with disabilities?” said she. In medical model, Utami explained that she got polio when she was four, which has made her unable to walk. Her parents tried to make her normal. She completely disagrees with this model. It sees disability as not normal.

The term of disable is itself a problem. Utami explained that in Indonesia it is still common to use “penyandang cacat” which refers to a person with “special needs.” Meaning, we are still labelizing them. In the concept of humanity, we should not define people as “disabled,” but as “persons” because we are using concept of humanity in advocacy. According to the Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities, which Indonesia and most other countries have ratified, all people with disabilities can enjoy all the same human rights as everybody else, including religious freedom.

The third article of CRPD calls for the recognition of human rights and human diversity. Indonesia has not fulfilled this point, as can be seen from how LGBT (Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender) Indonesians cannot be religious leaders. A man who is gay and has a ‘disability’ , for example, cannot be a leader for other men in praying. He can be the leader only for woman.. Another related example is that according to marriage law in Indonesia, a man can be divorced or marry a second wife is his wife becomes disabled. Utami argued that this is discrimination against persons with disabilities.

Utami told a her story about when she was young. Her caretaker carried her to Mushola, and all the people there were asking why she was being carried. In Indonesia, public buildings are not designed to adequately accommodate persons with disabilities. In contrast, Risnawati told another story about a Muslim friend in England who is blind and can go everywhere with his seeing-eye dog, including the mosque. This situation would not be possible in Indonesia. Utami said that this is homework for Islamic leaders: can they learn to allow a blind Muslim into the mosque with a dog in order to pray?. Utami also told about her experience in America when a pastor invited her to go to his church, which was in a building is accessible for wheelchairs. She felt she could fully participate in life in America.

Utami continued that there is a custum, when a disable enters the temple and they fall down, the temple should be purified. It is quite debatable with religious organization in Bali. What Utami and her organization have done is creating mediation. In Indonesia generally, there are many deaf organizations in helping Muslim with disabilities. When they could not hear Khutbah (Jum’at prayer), they provide sign language for Muslim with disabilities. Utami mentioned UIN Yogyakarta’s mosque as an example about friendly institution over the person with disabilities. There is sign language during khutbah and the building was designed for disable also. Utami told how the building should be designed universally, it will reduce physical barrier over person with disabilities. Regarding to the freedom of religion, Utami said that it is about attitude and perspective, and how to eliminate ignorance and prejudice. It is also about how people like her can also have access to themosque.

In Discussion session, Samsul Ma’arif asked about the relation between religious freedom and universal design for persons with disabilities. It is because the way he understood religious freedom is about how we are not necessary to have similar though in religion. Utami responded the question saying that universal design is to accommodate people to come to that building. For Utami, the building is part of socialization, how people can get access to the accessible worship place like masques or church. Religious freedom is not about only about the same rights, but also about equal access.

Following Ma’arif, Mark Woodward asked about the most reason they rely on international organizations and Utami answered the Indonesian government responds to international pressure more than to lobbying from its own citizens. Thus the CRPD is an important tool for social change in Indonesia. Meta, a CRCS student, also asked about Utami’s opinion that religion also makes them as charity object? Utami answered that she has a quite liberal perspective, and sometimes still accepts the charity concept or uses several model on the time. “I advocated for persons with disabilities so they will not be underestimated.”

Editor: Greg Vanderbilt

ABSTRACT

Hate speech is one of the factors contributing to sectarian and ethnic conflict. It typically includes social/psychological processes of dehumanization and demonization that define others as less than human and archetypes of evil. Often others are described as existential threats to the very existence of the speaker’s community. It is used to incite or justify violence, sometimes rising to the level of genocide. It is nearly often entirely inaccurate.

Hate speech is an under theorized mode of contentious discourse. It is easy to recognize and difficult to define precisely. In this paper I located hate speech within a four-point typology of contentious discourse: 1. Dialog concerning religious differences; 2. Unilateral condemnation of the beliefs and practices others; 3. Dehumanization and demonization of others and implicit justification of violence; 4. Explicit provocation of violence. For examples I rely primarily on the violent rhetoric of the Indonesian Islamic Defenders Front.

Dehumanization and demonization are the psychological processes that distinguish between civil discourse and hate speech. Levels 1 and 2 are critiques located within the limits of civil discourse because they do not implicitly or explicitly threaten others. Levels 3 and 4 are hate speech. They make symbolic associations that are inherently threatening.

Some forms of hate speech are universal or nearly so. Among these are the description of others as animals, evil, heretics and/or of engaging in “inappropriate” sexual conduct. Others are culturally or religiously specific. More research is required to understand the semantics of hate speech and how it transcends religious and ethnic boundaries.

There is an inevitable contradiction between defending freedom of speech, as guaranteed by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,and protecting people, usually minorities, from the psychological harm hate speech causes and the risk of physical violence it exposes them to.Legal restrictions do not eliminate hate speech; they only drive in from the public sphere. Most laws restricting hate speech were drafted long before the Internet and social media existed. Now, they are largely ineffective. Countering hate speech requires concerted effort by religious and political leaders and netizens across a range of media, including those used most frequently, including social media, by extremists who promote it. In this presentation I rely on examples from Front Pembela Islam (Islamic Defenders Front/FPI).

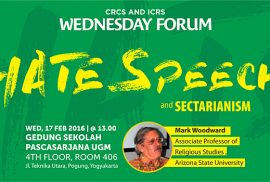

SPEAKER

Mark Woodward is Associate Professor of Religious Studies and is also affiliated with the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University. His research focuses on religion-state-society relations and religion and conflict in Southeast Asia. He is author of Islam in Java. Normative Piety and Mysticism in the Sultanate of Yogyakarta, Defenders of Reason in Islam (1989)and Java, Indonesia and Islam (2010) .He has published more than fifty scholarly articles in the US, Europe, Indonesia and Singapore, many co-authored with Southeast Asian scholars. He his currently directing a trans-disciplinary, multi-country project on counter-radical Muslim discourse.