Anang G Alfian | CRCS | Event

Issues of environmental damage are becoming more pervasive recently. It was just a few months ago we hear the voices of Samin community, indigenous people in the slopes of Mount Kendheng advocating environmental justice against industrialization attack surrounding the mountain, the issue of which inspired Dian Adi M.R., one of CRCS students, to compose instrumental music and conceptualize arts performance at the event called “Sounds of The Indigenous”.

Through his experience in music performance, Dian initiated the event and collaborated with various musicians, environmental activists, and academia of religious and cultural studies. This innovative way of giving collaborative performance is purposively to raise an awareness among various professions to work together on preserving nature.

Held at Taman Budaya Yogyakarta, many visitors crowded the event on the eve of January 25th 2017 to see the performance, which was started by a documentary film about the semen factory against Samin people and other environmental issues happening recently. Some commentaries from local peoples, scholars, and villagers were narrating a number of environmental problems especially in dealing with actors of interests and exploitation of nature. There is a need of consolidation and urgent answer to avoid further consequence of human misconducts toward nature.

As the introduction to the theme was read, a theatrical performance began to tell narratives and stories, and the instrumental music slowly echoed and filled the air of the room. Visitors seemed to enjoy the mystical yet artistic nuances coming out of the cello playing. Throughout the performance, music and theatrical arts were integrated and made a harmonious blend.

Some instruments were used to represent different and rich sounds from different cultures and origins. Besides guitar, violin, and other common instruments, there were also Gambus, a Middle Eastern music instrument played in the end of the session with Arabic vocal. A Dayak instrument called Sape was also used to sing with a children song. It produced a nostalgic scene of happy life when children can play with nature before industrialization has polluted environment and water.

A theatrical narrative called “Hunger” was also enacted to convey indigenous voices demanding justice and prosperity. The story was meant to see how the man’s greed is always the cause of destruction. “Those local cultures are indeed real guardians of the nature, while ironically many intellectuals go with the interests of those people to build their projects ignoring the locals and the environment,” said Dian commenting on the theme of the performance.

Music can be a means to harmonize the relation between human and nature and awaken the awareness of the shared duty to preserve nature. Justitias Jellita, the Cello player, reflected on music as being in a harmony as she said, “The harmony is not only for musical tunes, but also for the self and the universe. Without harmony, journey of life will lose its meaning, and those who can return to his home is the ones that know where they come from. This Sounds of the Indigenous event is a valuable message and important warning that human will return to his home “Earth” anyway. Therefore, while alive, we’re responsible for our home.”

Music can be a means to harmonize the relation between human and nature and awaken the awareness of the shared duty to preserve nature. Justitias Jellita, the Cello player, reflected on music as being in a harmony as she said, “The harmony is not only for musical tunes, but also for the self and the universe. Without harmony, journey of life will lose its meaning, and those who can return to his home is the ones that know where they come from. This Sounds of the Indigenous event is a valuable message and important warning that human will return to his home “Earth” anyway. Therefore, while alive, we’re responsible for our home.”

Indigenous people of Dayak tribe have their own cosmology on their music as what Anang, the Sape player, said, “For Dayak people, they believe an old saying, ‘Sapeh Benutah tulaang to’awah,’ meaning Sape can crush the bones of evil ghosts.”

This event has given us a lesson on how to maintain the relation between man and nature as important elements in the harmony of life. And music is one of the languages the indigenous speak with. Now it is our turn whoever we might be; artists, scholars, or environmental practitioners; to know where we stand on and where we are going to return.

*Anang G Alfian is CRCS student of the 2016 batch

Berita

Abstract

Iranian cinema is one of the very few in the Muslim world to have employed this new medium in imagining and narrating stories of religious figures. The representation of religious figures in Islam has become particularly controversial in recent years. Therefore, it turned into a highly sensitive undertaking. In this talk I examine the complex socio-political context of Iran to study late emergence of the epic genre in Iranian cinema. In doing so I study the recent creation and development of ‘Qur’anic Films’ within Iranian cinema with specific reference to Kingdom of Solomon (Mulk-i Sulayman-i Nabi, Shahriar Bahrani, 2010), which I argue is the first Qur’anic epic in Iranian cinema if not in the Muslim world.

Speaker

Dr Nacim Pak-Shiraz is the Head of Persian Studies and Senior Lecturer in Persian and Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh. She is the author of Shi’i Islam in Iranian Cinema: Religion and Spirituality in Film (London, 2011) and a number of articles and chapters in the field of Iranian Film Studies. Dr. Pak-Shiraz also regularly collaborates with a number of film festivals, including the Edinburgh International Film Festival and The Edinburgh Iranian Festival.

Abstract:

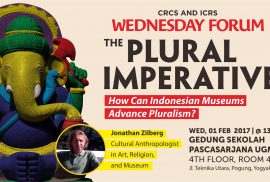

In this discussion, Jonathan Zilberg will discuss problems fracing Indonesian museum in terms of performance, accountability and transparency. He will discuss the Goverment of Indonesia’s 2010-2014 museum revitalization program, the transformations that have been taking place in Indonesia museum over the last decade and the challenges posed for the future. He will look at museums as democracy machines and as postcolonial centers for advacing the ideology of pluralism in civil society. In particular he will address the integrated importance of museums, adchives and libraris for advacing the state of education at all levels including for countinuing adult education.

Speaker:

Jonathan Zilberg is a cultural anthropologist specializing in art and religion and in museum ethnography. He has been studying Indonesian museums for a decade and is particularly interested in museums as democracy machines and as post-colonial centers for advancing the ideology of pluralism in civil society. His immediate interests focus on Hindu-Buddhist heritage including the function of archaeological sites as open air museums as well as of museum collections and government depositories in terms of being under-utilized academic resources. For comparative purposes, he has studied museums in Aceh, Jambi, Jakarta and to a lesser extent observed select museums elsewhere in Indonesia. Currently he is CRCS UGM Visiting Scholar.

Abstract:

The Green Santri Network aims to be a socio-ecological movement by Indonesian Muslim groups, using Muslims’ own sensibility and ‘thought language’ to effectively disseminate messages about Islamic ecological values for survival and sustainability and to advance the idea of relocalization, or returning to a smaller scale, as self-reliant communities with simpler ways of living and with self-local governance. It comes out of my research into how Indonesian Muslim groups, including both the large-scale Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama and two examples of green intentional communities, Hidayatullah and An-Nadzir, can contribute toliving knowledge transmission or murabbias a way to make sustainability education relevant in the Islamic symbolic universe in the Indonesian context,based on the understanding that more than intellectual ability is needed to comprehend this knowledge; it must be made personal by living it.

Speaker:

Wardah Alkitiri earned her Ph.D. in Sociology at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, in 2016. Her dissertation was entitled “Muhammad’s Nation is called “The Potential for Endogenous Relocalisation in Muslim Communities in Indonesia”. She is founder of AMANI, a not-for-profit organization that aims to promote ecological sustainability through entrepreneurial creativity in Jabodetabek and Central Java.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Al Makin, a lecturer from ICRS and Ushuluddin Faculty in UIN Sunan Kalijaga, gave a fascinating presentation about his newest book Challenging Islamic Orthodoxy (Springer, 2016). He began his presentation by commenting that his research on prophethood in Indonesia may not be very new to the ICRS and CRCS community, but discussion of the polemics of prophethood is interesting as Indonesia is home for both the largest Muslim population of any country in the world and to many movements led by self-proclaimed prophets after the Prophet Muhammad. In Al Makin’s perspective, we should see this phenomenon from a different perspective, as part of the creativity of Indonesian Muslim society.

In 1993, the Ministry of Religious Affairs issued a selection of characters of what constitutes religion, include the definition of the prophet, a requirement of recognized religions. According to the Ministry of Religious Affair, prophets are those who receive revelation from God and are acknowledged by the scripture. However, following Islamic teaching, Muhamad is the seal. God no longer directly communicates with humankind. In Al Makin’s definition, prophets are those who, first, have received God’s voice and, second, establish a community and attract followers. He also reported that the Indonesian government has listed 600 banned prophets that fit these criteria. Interestingly, Indonesian prophets tend to come from “modernist” backgrounds connected to Muhammadiyah, which rejects other kinds of traditional and prophetic religious leadership, like wali and kyai.

After two years of trying, Al Makin gained complete trust from one well-known prophet in Jakarta, Lia Eden, and her community of followers. The wife of a university professor, Lia Eden was famous as a flower arranger and close to members of President Suharto’s circle. She quit her career when she was visited by bright light she later identified as Habibul Huda, the archangel Gibril. After that, she became prolific in her prophecies. She found many skills that she had not had before, like healing therapy. Her circle become a movement called Salamullah, meaning “peace from God” but also referring to salam or bay leaves, used in her healing treatment.

In orthodox Islam, there are no women prophets and no prophets after the Prophet himself. The ulama declared her and her followers heretics. Lia Eden returned the criticism, accusing the ulama of being conservative and criticizing Islam as an institution, especially how the ulama council uses its political power and authority.

Al Makin closed his presentation by showing the way public has responded to Lia Eden. This movement can be considered a New Religious Movement sparks controversy because of how they attract followers. In Indonesia it is more about theology than political or economic interest like it is elsewhere. Ultimately, Al Makin argues that Indonesia’s prophets should be recognized as unstoppable—they usually become more active when in prison—but should be seen as part of the wealth of Indonesia pluralism.

Al Makin responded to a question from Mark Woodward about why Lia Eden’s community with only 30 members would become such a big problem for the government by citing Arjun Appadurai, who has argued that a small number becomes a threat to the majority in terms of its purity. It is true that she has a very small number of followers but she is also very bold and outspoken in deliver her messages constantly sending letters to many political leaders, including the ambassadors from other countries and issuing very public condemnations. Greg, another lecturer from CRCS, also asked why she is called bunda and whether she is making a gender-based critique. Al Makin answered that there have been a few other women prophets besides Lia Eden in Indonesia and that Lia Eden’s closest associates are women.

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Class Journal

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

As an American lecturer who has been working with CRCS since 2014 through Eastern Mennonite University, Virginia, he is a very well-experienced educator as he previously spent some years teaching in Japan. Moreover, his interest in following up the up-dated global issues including religious nuances, made him familiar with framing the methods of studying religion and globalization.

Global ethics is one of the topics we discussed in the class, the last material before the end of the class. Previously, we talked a lot about globalization as a phenomenon affecting religions as well as several religious responses toward globalization. Despite the supporters of globalization, many religions seem to fearfully reject it, some even proclaiming their resistance and becoming more radical.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Therefore, to foster the stabilization of the world order from war and disputes, it is necessary to rethink globalization in ways that are more ethical and friendly to the world. On the topic discussion of global ethics, we learned about attempts by world organizations like the United Nations in generating international agreements including the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Besides, other agreements such as the Cairo and Bangkok Declarations represent local voices which to some points define human rights differently.

The difference in worldviews among international actors is interesting because each organization tries to define a global value within their own relativities. Moreover, some theories think that UN Declaration on Human Right is a Western domination over other cultures without considering cultural relativities, including religions, each of which inherits different theological and structures while at the same time sharing common values like peace, humanity, equality, and justice.

World issues indeed became valuable perspective in this class. Students are meant to not only understand theories but also keep updating their knowledge on what is happening in the recent international world. While negative influences of globalization such as war, religious radicalization, and other world disputes were discussed in the class, there is also a hope for a global agreement and bright future by sharing noble values like cooperation, justice, human dignity, and peace on global scale. The existence of world organizations and religious representatives in fostering global ethics proves the progress made towards creating world peace. The duty of students, in this case, is to contribute academically to spreading such values without neglecting the variety of cultural and religious perspectives.

*The writer is CRCS’s student of the 2016 batch.