Aksi Super Damai 212 patut diapresiasi sebagai bukti kemajuan dan kedewasaan umat Islam Indonesia dalam mengekspresikan aspirasi politiknya. Kesejukan yang hadir dalam aksi ini sudah seharusnya diapresiasi.

Namun demikian, bagi peserta aksi, tujuan mereka bukan sekadar membuktikan bahwa Aksi Bela Islam adalah gerakan damai. Ratusan ribu atau bahkan lebih dari sejuta orang bersusah payah mendatangi Jakarta dalam aksi 212. Sebagian bahkan rela jalan kaki berhari-hari demi “membela Islam”, dengan tuntutan memenjarakan Ahok. Menariknya, meskipun Ahok tidak ditahan, para peserta aksi 212 tampak pulang dengan perasaan menang.

Sampai esai ini ditulis, perayaan kemenangan masih berlanjut. Linimasa masih dibanjiri konten dan unggahan yang menunjukkan kedahsyatan momen setengah hari di bawah Monas itu. Sebagian bahkan menawarkan cenderamata dan kaos untuk mengenang momen kemenangan.

Lantas pertanyaannya: apa yang sebenarnya telah dimenangkan?

Perang Posisi, Bukan Perang Manuver

Bagi banyak orang, partisipasi dalam aksi 212 bisa menjadi bagian dari momen langka yang tidak terlupakan. Berada di tengah lautan manusia untuk “membela Islam” merupakan kepuasan spiritual. Aksi yang begitu besar, yang dilakukan dengan tertib dan tanpa menyisakan sampah, adalah sebuah kemenangan dalam melawan wacana atau tuduhan tentang ancaman kekerasan dan makar.

News

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

“Like the study of feminism, masculinity can be an important approach in religious studies. The study of masculinity emphasizes how man superiority has been graded or perceived from time to time that in turn it becomes a norm for society.”

“Like the study of feminism, masculinity can be an important approach in religious studies. The study of masculinity emphasizes how man superiority has been graded or perceived from time to time that in turn it becomes a norm for society.”

Rachmat Hidayat, a Project Director in Kalijaga Institute for Justice, State Islamic University Sunan Kalijaga, who shared his research in the weekly CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum, September 14, 2016, is and experiences about Muslim men from three Southeast Asia countries—Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia—living for years in Australia. His research questions are grounded in the problem of masculinity in Islamic studies.

In Muslim majority society, the figure of man is portrayed as the “imam” or, in a very general sense, the leader of the family. In the Muslim based society, the doctrine that male is the leader is embodied in the daily practices. The role as man in Muslim families anchors their responsibility in leading the household but, in contrast to the men living the non-Muslim society, the meanings and understandings change.

Building a framework that can help masculinity to be accepted in Islamic studies, Hidayat argued that just like the study of feminism, masculinity can be an important approach in religious studies. In general, the study of masculinity emphasizes how man superiority has been graded or perceived from time to time that in turn it becomes a norm for society.

The problem of masculinity in Muslim men living in Australia is in the sense of manhood within the family structure. In such context, the challenges are coming from the liberal and secular societies. Before explaining more about that problem, Hidayat described masculinity and how it works in the society. Masculinity is taking man as a gendered subject and perceiving men’s identity as related to but different to women. Men’s identity was constructed within certain historical, cultural, and social process. But this construction and the identity itself changes from time to time.

Furthermore, Hidayat asserted that gender construction and the meaning of the self is something that people define and negotiate every day because the discourse of the self is related to other. There are valves imply in Men’s identity. The gender construction adding the values such as bravery, toughness, rationality, to men’s identity and make people unconsciously define men in those values. In doing so, in Muslim community, being a man means being religious and strong at the same time. The practices of being a man in Muslim based society are included the practice of competition, dominance, and fathering. It shows that performance as a man cannot be separated to the relation with woman and kids.

Masculinity only can be defined and identified in the relationship therefore to study about masculinity in Islamic Studies, the approach must be done by examining men also as religious gender actors. In the context of secular of Australian society, the Muslim men identify challenges by some unfamiliar condition. Muslim men need to negotiate their position under the relation that lies between the Muslim women-Muslim brotherhood-the divine and the society itself.

With their various background, the 25 Muslim men in Australia whom he interviewed compromise and negotiate their position as Imam in their daily basis which relates to the men’s role as bread-winner in family. Facing the adversity and limitation, the Muslim men build their survival mechanism. In that survival mechanism, men need to share the authority, responsibility, and power to their partner who have more opportunity to get the money. Hence, some Muslim women replace the role of Men as bread-winner.

Responding to those facts, Samsul Maarif from CRCS asked whether women might also have masculinity and thus the term masculinity is not exclusive for men. “Masculinity, like feminine, is construction and it shows particular quality rather than embedded on sex,” said Hidayat. Within this framework, Muslim Southeast Asian women in Australia who perform their role as bread-winner also have masculine quality. However, as Hidayat underlined, men’s role as Imam is a non-negotiable status for men. Thus, responding to the challenges in every day live in Australia, Muslim men adopt some norm and apply it to the family as an act of negotiation. For example, the practice of partnership and individual freedom equality. Even when the wife becomes the bread-winner, the husband still has authority to manage the family. Furthermore, by giving permission to the wife for working, a husband serves their role as humble and just Imam because he aware of its limitation and humbly accept it. Hence, now Muslim men understand the role of Imam differently: as an act to love, to sacrifice, to share, and not being selfish with their family member.

Abstract:

During the past two decades, Malaysian Muslim female preachers have gained access to opportunities and spaces to preach Islam to the public. Their preaching activism, both through the mass media and from public pulpits, is seemingly an indication of a shift in religious authority in contemporary Islamic discourse in Malaysia. They have gained trust from the public and become authoritative voices of Islam through acquiring knowledge of the fundamental texts of Islam as well as required skills such as Arabic language, memorization of religious texts and public speaking. Just like the male preachers, they have dedicated themselves to creating a sound moral and ethical society based on Islamic framework. They preach to the public on various issues, including moral-spiritual endeavors, socio-religious advice and practices, and marital and family relations. One vents based on the Islamic calendar. Nevertheless, the female preachers have to navigate their activism within the confines of social norms and of the highly-bureaucratized religious authority and administration. By adhering to social expectations and religious orthodoxy, the female preachers are able to continue preaching to the public, as well as to build trust with both the established religious authorities and the public.

Speaker:

Norbani Ismail is the Malaysia Chair of Islam in Southeast Asia at Georgetown University’s Prince al-Waleed bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, School of Foreign Service. She has a PhD in Islamic Studies from the International Islamic University Malaysia and is currently working on a book monograph that explores twentieth-century interpretations of the Qur’an in Indonesia and Egypt. Her research interests include Muslim women’s religious activism in Malaysia and trends in Islamic reform in contemporary Malaysia.

Abstract:

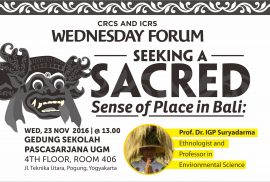

Every tradition in the world employs symbolism, but symbolism reaches acme in Hinduism. However, modern communities seem to be missing the meaning of symbolism. Most of Indonesian ethnicities, especially the Balinese, hold certain views about reality of the world, including the interconnection between the reality of the world and metaphysical world, setting aside days and ceremonies to honor plants, animals, and even inanimate objects have extrinsic and intrinsic value of sacredness. Balinese Hindus are very practical in their religion, striving for the realization of God in daily life, creating oneness and unity with all life on our physical plane and seeking to become sources of light and ambasador of peace.

Speaker:

Prof. Dr. I Gusti Putu Suryadarma is an ethnologist and professor in environmental sciences. He earned his PhD at Bogor Agricultural University on Natural Resources Management. Currently he teaches at Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Science, Yogyakarta State University.

“Laporan ini menunjukkan bahwa dalam banyak kasus, Pilkada turut berperan dalam terciptanya struktur kesempatan politik yang memungkinkan mobilisasi dan peran kekuatan-kekuatan sosial yang mengusung ideologi intoleran.”

“Laporan ini menunjukkan bahwa dalam banyak kasus, Pilkada turut berperan dalam terciptanya struktur kesempatan politik yang memungkinkan mobilisasi dan peran kekuatan-kekuatan sosial yang mengusung ideologi intoleran.”

Laporan Kehidupan Beragama di Indonesia ini mengkaji peran pilkada sebagai struktur kesempatan politik bagi menguatnya konflik atau kekerasan keagamaan. Tanpa bermaksud mendelegitimasi Pilkada langsung, Laporan ini mengulas tiga kasus kekerasan terkait hubungan antar dan intra-agama. Ketiga kasus ini dihadirkan untuk memberi ilustrasi pentingnya mengantisipasi efek samping dari Pilkada terhadap situasi keragaman agama di Indonesia.

Ketiga Kasus tersebut adalah kekerasan terhadap Masjid Ahmadiyah dan beberapa gereja di Bekasi (Jawa Barat), kekerasan terhadap penganut Syiah di Sampang (Jawa Timur), dan sengketa pembangunan Masjid Nur Musafir di Kelurahan Batuplat, Kota Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur). Ketiga kasus ini dipilih untuk memberikan ilustrasi tentang pentingnya memperhatikan Pilkada sebagai masa kritis yang bisa menentukan pola hubungan antar-agama.

Dengan demikian, bertujuan untuk memberikan pemahaman mengenai peta permasalahan terkait kehidupan beragama, beberapa karakternya, dan peluang-peluang atau cara-cara konstruktif untuk menanggapinya. Hasil pemetaan menunjukkan bahwa sesungguhnya selama 15 tahun terakhir ini, ada beberapa jenis isu utama yang muncul secara konsisten. Misalnya, sementara kekerasan komunal berskala besar cenderung menurun secara tajam, namun kekerasankekerasan sporadis yang terkait dengan “penodaan agama” atau isu pembangunan rumah ibadah tampak makin intens; isu lain yang kerap muncul sebagai akibat demokratisasi adalah menguatnya wacana pro-kontra terkait pembuatan kebijakankebijakan publik, baik pada tingkat nasional maupun lokal.

Laporan ini bisa diunduh: http://wp.me/P5Fa8A-4P

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

In a world so full of complexity, how does intimacy work? To Dian Arymami, it is very significant and important to revisit the understanding of intimacy because she observes the transformation of intimacy is connected to the transformation of society. The practice, the understanding of intimacy have been reconstructed from time to time. Usually people would think about intimacy as an act of loving, but up to now there are many cases show that intimacy could be something out of love, outside of committed relationship and, to be more precise, outside of marriage. Moreover personal needs and desires are also part of our religiosity. Religiosity and intimacy are not totally opposed to each other.

Dian Arymami’s ongoing research on new kinds of intimacy in the phenomenon of extradyadic or non-monogamous relationships that have quickly become widespread in urban areas of Indonesia is not advocacy on behalf of a group of people but she insists that she is studying the voices of the voiceless. Their emergence can be seen on a practical level as a rebellion against the structure and social fabric of Indonesian society but at the same time as part of an ongoing shift of ideological values and norms. Those who practice extradyadic relationships are a voice that could not be heard by the society because people would always claim that the problem is in person not society. We must think about this kind of intimacy as a social phenomenon and not a personal disease or failing.

Therefore, Dian came up with the signs of embodied practice of intimacy in the schizophrenic society. It related to something that material not representation. It is social not familial and she continue by saying that it multiplicity not personal. Many things transform relationships. According to the cases that Dian come up with, the social media is one of the biggest influence in transforming relationship in society. The discourse about intimacy embodied in the way people perceive things like divorce, sexuality, dating style, poly-amor trend and many others to follow. To define schizophrenic society, she refers to the theory of Gilles Delueze and Felix Guattari about the process of schizophrenia. Unlike Freud’s understanding about paranoia, the schizophrenic term in Delueze shows a condition of an experienced of being isolated, disconnected which fail to link up with a coherent sequence. She than continues that no one is born schizophrenic. Instead, schizophrenia is a process of being. In the schizophrenic society, everyone experiences diverse meanings in relation to other objects, and, in the other times or places, no meaning at all. In other words, meanings are based on the schizophrenic’s object experiences, but it is society itself that must be understood as schizophrenic.

By highlighting her respondents’ experiences, Dian shows that there are many consequences of the practice of intimacy or intimate relationships in (as) the schizophrenic society including “value crash,” double life, “time and place crash” and many others. In extradyadic relationship people become a substitution for something that they cannot fill.

In the question and answer session, there were many fascinating questions about this topic. Zoyer, a researcher concerned with on-line dating in Yogyakarta, offered the idea that the complexity of intimate relationships in urban areas in Indonesia is affected by the cultural expectation that young people marry by certain ages. That is why people are trying to free themselves by “jumping into the extraordinary.” The other question brings us to a reflection about what are the practitioners of these extradyadic relationships are becoming in society. Dian answered by changing the question: instead of questioning a person’s behavior, we must question society. Dian closed her remarkable presentation by stating that the idea of love is not exclusive and absolute.