Anang G. Alfian* | CRCS | Class Journal

Salah satu mata kuliah yang diajarkan di CRCS adalah Religion, Violence, and Peace Building (Agama, Kekerasan, dan Perdamaian). Tiga kata kunci ini menjadi variabel dan titik tolak diskusi tentang hubungan agama dan konflik sosial dan bagaimana upaya untuk membangun perdamaian.

Diampu oleh Dr. Iqbal Ahnaf, mata kuliah ini membahas, antara lain, persoalan relasi antara agama dan konflik. Ini dibahas di pertemuan pertama untuk membuka wawasan tentang perdebatan yang terjadi mengenai hubungan kausalitas antara agama dan kekerasan.

Pada pertemuan ini, satu dari dua bacaan yang dipakai sebagai bahan readings adalah artikel dari Andreas Hasenclever dan Volker Rittberger, Does Religion Make a Difference?: Theoretical Approaches to the Impact of Faith on Political Conflict (Journal of International Studies, 2000).

Dalam artikel itu, Hasenclever dan Rittberger memaparkan tiga mazhab dalam dunia akademik dalam membaca hubungan agama dan konflik, yaitu (1) primordialis, (2) instrumentalis, dan (3) konstruktivis.

Kaum primordialis berpandangan bahwa agama dalam dirinya sendiri memiliki unsur inheren yang dapat menyebabkan konflik. Ketika terjadi “konflik agama”, agama dibaca oleh kaum primordialis sebagai variabel yang independen, unsur yang tidak bergantung pada aspek-aspek lain, dan perbedaan identitas keagamaan itu sendiri bisa cukup sebagai penyebab konflik.

Kaum instrumentalis melihat peran agama dalam “konflik agama” sebagai instrumen saja, dan tidak memiliki peran objektif dalam dirinya sendiri. Menurut kaum instrumentalis, penyebab utama konflik adalah kepentingan politik dan ekonomi. Bagi kaum instrumentalis, agama hanya berperan dalam retorika saja, dan relasinya dengan konflik bersifat semu belaka.

Kaum konstruktivis tampak berada di tengah-tengah antara kedua kelompok di atas. Konstruktivis bersetuju dengan instrumentalis dalam hal bahwa penyebab fundamental konflik bukanlah agama, melainkan kepentingan politik dan ekonomi. Namun konstruktivis juga bersepakat dengan primordialis dalam hal bahwa agama memiliki peran nyata objektif, namun bukan sebagai penyebab utama, melainkan eskalator konflik. Agama, ketika terlibat dalam konflik, dapat membuat konflik semakin mematikan, deadly. Juga, berbeda dari primordialis yang berpandangan bahwa agama menjadi variabel independen dalam konflik, bagi kaum konstruktivis agama berperan secara dependen, tergantung pada faktor-faktor ekonomi dan politik lain yang melingkupi konflik tersebut; seberapa besar peran agama mengeskalasi konflik tergantung pada seberapa akut benturan antar kepentingan politik dan ekonomi dalam konflik itu.

Ketiga cara pandang di atas tidak bisa diperlakukan secara universal. Tapi ketiganya bisa dijadikan lensa analitis dan ditempatkan dalam suatu spektrum. Bagaimana menentukan peran agama dalam suatu konflik mestilah dimulai dari detil kasus konfliknya, lalu naik melihat lensa-lensa analitis yang ada, kemudian menentukan di antara yang tersedia manakah penjelasan yang lebih tepat.

Dalam “kasus Sunni-Syiah” Sampang, misalnya, dimensi konflik yang terjadi bukan hanya karena faktor perbedaan ideologis semata, namun juga karena adanya instrumentalisasi agama oleh elite politik, karena konflik ternyata bereskalasi pada masa perebutan kekuasaan menjelang pemilu daerah, sehingga narasi-narasi agama di legitimasi sedemikian rupa untuk suatu tujuan politik. Dalam melihat hal ini, kita tak bisa berhenti pada pandangan kaum primordialis—inilah pandangan yang diadopsi oleh mereka yang memercayai bahwa konflik Sampang itu adalah konflik Sunni-Syiah. Dimensi sosial politik dalam konflik itu wajib dihitung, mulai dari yang kecil seperti persengkataan internal keluarga, perebutan umat, hingga yang lebih makro seperti instrumentalisasi konflik untuk mendulang dukungan dalam pemilu.

Dalam perspektif konstruktivis, intervensi terhadap konflik dengan menyuarakan nilai-nilai kebajikan agama, kearifan lokal, dan slogan-slogan orang Madura Sampang sangat membantu upaya rekonsiliasi konflik, yakni untuk melakukan deskalasi terhadap konflik itu dengan mengajukan narasi tandingan primordialis. Penelitian Dr. Iqbal Ahnaf beserta peneliti yang lain dalam serial laporan CRCS tentang kehidupan beragama di Indonesia yang bertajuk Politik Lokal dan Konflik Keagamaan menunjukkan instrumentalisasi agama oleh elit politik di Sampang menjelang pilkada. Tesis S2 terkait kasus Sampang ini juga ditulis oleh mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2010 Muhammad Afdillah yang kini telah dijadikan buku dengan judul Dari Masjid ke Panggung Politik.

Kasus Sampang merupakan contoh yang bagus untuk membaca seberapa besar peran agama dalam konflik, dan ini membutuhkan data dan analisis yang cermat. Contoh-contoh lain dari yang terjadi di Indonesia yang bisa diambil ialah kasus Ambon dan Poso, atau yang belum lama ini terjadi seperti di Tolikara, Tanjungbalai, atau bahkan kasus dugaan “penodaan agama” dalam pilkada Jakarta.

*Penulis adalah mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2016

CRCS

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Article

“Jesus as an infant fled with his family into exile. During his public life, he went about doing good and healing the sick, with nowhere to lay his head”.

We were finally in the next to last meeting of Religion and Globalization class. Having studied religion and globalization through the whole sessions, we have come to understand a lot about what role of religions play in accord to globalization and how globalization affects the way religions are concerned with humanitarian issues.

On Monday, November 21, 2016, we had a field trip to one faith-based-NGO to understand how such religious organization works for humanity. Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is one of the well-known international organizations and it was a good place to learn the working field of faith-based organizations. Together with Gregory Vanderbilt as the lecturer of the class, we visited the national office of JRS in Yogyakarta and had a great time meeting Fr. Maswan, S.J., and learning directly from a member of the community

Our visit began with Fr. Maswan’s presentation about the organization. Firstly established in Indonesia in 1999, Jesuit Refugees Services has been accompanying, advocating, and giving services to forcibly displaced people. Therefore, this organization has actually been well experienced in dealing with the issues. As we listen to his presentation, we come to realize that this problem of refugees and asylum seekers cannot be ignored for it belongs to international concern. The perpetuation of war, disasters, racial conflict, and many other causes make refugees seek for their safety life by migrating to other national boundaries.

Our visit began with Fr. Maswan’s presentation about the organization. Firstly established in Indonesia in 1999, Jesuit Refugees Services has been accompanying, advocating, and giving services to forcibly displaced people. Therefore, this organization has actually been well experienced in dealing with the issues. As we listen to his presentation, we come to realize that this problem of refugees and asylum seekers cannot be ignored for it belongs to international concern. The perpetuation of war, disasters, racial conflict, and many other causes make refugees seek for their safety life by migrating to other national boundaries.

However, it has never been easy for refugees because they have to face the legal and often difficult administrative regulations of the government where they are staying. This is exactly what happens to refugees in Indonesia. Because Indonesia has not ratified the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, refugees in Indonesia are not recognized as such by the Indonesian government—instead they are considered undocumented aliens—while they wait for recognition from the UNHCR which will allow them to resettle in another country. In some districts, refugees have to stay in detention center while waiting for their legal refugee status to be acknowledged by the law.

As recorded in JRS monitoring, refugees in Indonesia have reached a number of 4.344 people of whom 540 are female and 905 are children with 96 being unaccompanied minors and seperated children. So far, JRS has been accompanying two detention centers in Surabaya and Manado and being involved in other areas as well. In Aceh, JRS has advocated for protection over 625 people and has given psychosocial accompaniement to over 1558 refugees. In Yogyakarta, they are serving the refugees, mostly from Afghanistan, housed in the Ashrama Haji. They listen, accompany, and make activities to give hope for those people who had been separated from their family and their mother land.

So, where is exactly the religion to deal with this? This question come out of students trying to figure out the role of religion in this humanity organization. Then, the community member continued the presentation stating that the mission of JRS is intimately connected with the mission of Society of Jesus to serve faith and promote the justice of God’s kingdom in dialogues with cultures and religions. Yet, another student comes up with another concern, “Does it mean that JSR proselytize Christianity?” Well. This is very important because in the previous meeting, we read through Philip Fountain’s “Proselytizing Development” and he himself attended our class for discussing this topic. In sort, the religion has been inspired by the development organization as precedent in history while, vice versa, religion brings universal ethics to be put in dialogue with cultures and religion.

In the last session of our discussion in JRS offices, Fr. Maswan emphasized some points such as it is the problem of humanity that we have to be concerned about and not at all concerned in religious kind of missionary work altough it might inspired the organization in its underlying ethics, building cooperation with other cultural, faith-based, and other types of organization. We also read the paper Fredy Torang (2013 batch) presented in Singapore about how JRS acts as an agent of “humanitarian diplomacy” between the refugees and the local communities and government. In 2017, JRS will continue lobbying local government to allow refugees to live in a community and not in detention and also monitoring the migration all over the world to help assisting the displaced people and consistently gives concern to human right and dignity.

In the last session of our discussion in JRS offices, Fr. Maswan emphasized some points such as it is the problem of humanity that we have to be concerned about and not at all concerned in religious kind of missionary work altough it might inspired the organization in its underlying ethics, building cooperation with other cultural, faith-based, and other types of organization. We also read the paper Fredy Torang (2013 batch) presented in Singapore about how JRS acts as an agent of “humanitarian diplomacy” between the refugees and the local communities and government. In 2017, JRS will continue lobbying local government to allow refugees to live in a community and not in detention and also monitoring the migration all over the world to help assisting the displaced people and consistently gives concern to human right and dignity.

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Article

The national news was shocked by a presence of nine middle-aged women pouring cement on their feet. It was on 13th April 2016, and the ‘Nine Kartini’ had made a long march from their villages in central Java to Jakarta to protest in front of Presidential Palace against a plan to build a cement company in Kendheng Mountain near Rembang, Pati, Grobogan.

Wanting to know more and study the problems faced by those women as well as the Samin indigenous culture, CRCS and ICRS students and lecturers traveled to Kendheng on Thursday-Friday, 24-25 November. This trip was aimed to give students an understanding of the real problems faced by the minority in preserving their lands and the place of religion and spirituality in their struggles.

Samin people have been famous recently for their resistance to cement production in Kendheng. Naming their community after their charismatic leader of the past, Samin Surosentiko, they have adopted his values of non-violence, reverence for life, resistance to injustice, bravery, and honesty.

In this trip, we were going to reflect what we had studied in the class involving subjects like religion and ecology, academic study of religion, and religion and conflict. Accompanied by Dewi Candraningrum, a feminist scholar and guest lecturer in our religion and ecology class, we were guided to reach their place in Sukolilo, Pati.

It took a five-hour journey by car to get there. As we arrived at Omah Kendheng, the place where Samin people gather, we were welcomed with warm hospitality. In the house with a wall made of woods and decorated with jugs attached around the wall, we catch an impression of a traditional Javanese nuance. There was also a gamelan in the right corner of the hall used by Samin people to preserve Javanese music and educate teenagers of their inheritance. Pak Gunretno, the leader, greeted us and served us lunch before we had discussion as planned.

Soon after that, we introduced ourselves and began the discussion. Started from Pak Gunretno, some important figures shared their explanation that the resistance to the cement company was because they want to preserve Kendheng Mountain. They proclaimed that it was their duty to preserve what they inherit from their ancestors. For them, nature is like a mother because it gives birth to natural resources for humans to consume. Therefore, exploiting it will only make the nature imbalanced and suffering from severe damage. Moreover, they argued that Central Java is supposed to be the source of rice fields and not exploited for underground materials.

Moreover, they explained about their refusal to receive a formal education. For them, the goal of education is to teach how to behave in a good way and live with wisdom. They are also famous for not taking any profession or occupation besides farming because they believe that the farm itself is enough to give them life. Other questions about their resistance and history were also asked by the students. Finally, the discussion ended in the early evening and we continued watching movie made by them as their resistance to the cement company. The next day, we visited some places like the forest where the source of water used for the field irrigation and we ended up in the sacred tomb of spiritual figure. The forest has been preserved and it is forbidden for anyone, including locals, to exploit it. The sacred tomb is the place where people sometimes gather to pray and have rituals.

Finally, before we had to go back to Jogjakarta, we discussed with the lecturers about what we had learned from this community. Zainal Abidin Bagir, the head of CRCS and the lecturer of Religion, Science, and Ecology, argued that the mountain is their identity and they cannot live without it. That is why they struggle so hard for preserving the mountain from mining production. They were really dependent on water and land. Moreover, he said that we can also articulate the interdependency of knowledge and authority. In this case, Samin people has been much influenced by their charismatic leader, Pak Gunretno, who leads the movement. However, this kind of knowledge-authority relationship is also there within academic life like the production of science that inevitably has to bow to certain authority.

Nevertheless, this trip opened our minds to the problems of minorities and modern life. It is interesting how indigenous religion has to struggle for preserving the mountain but, on the other hand, modern world demands more natural resources for consumption. In religion and conflict perspectives, for instance, we can observe this soft resistance of Samin people and what possible ways there are to reach for a solution. Many perspectives and experiences are as well needed to contribute and get involved in the academic study of religion.

Azis Anwar Fachrudin | CRCS UGM | Opinion

Despite the fact that Jakarta Governor Basuki “Ahok” Thahaja Purnama has apologized for statements made regarding the Quranic verse Al-Maidah 51, some Islamic groups are saying that an apology is not enough. Protestors demanded that Ahok be criminalized in a rally last week in Jakarta.

Deputy secretary-general of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) said on a TV show that religious defamation must be punished by “death, crucifixion or at least hand amputation and expulsion”. Even though he did not urge the state to adopt such a policy, but rather called on the processing of the case in accordance to the law on religious defamation, his remarks give the impression that Islamic law is that harsh.

The Quranic verses quoted by the MUI deputy secretary-general are known as the hirabah verses. Hirabah, which literally means “warfare”, and the verses were basically applied under the principles of Islamic jurisprudence to crimes such as highway robbery, piracy, unlawful rebellion and sedition. The verses were the same verses used by the Islamic state (IS) group to justify its crucifying of those waging war against IS.

Therefore, the attribution for those punishments for alleged religious defamation is dangerous.

What is more saddening is that Islamic groups are pushing for Ahok to be criminalized when he had no intention of insulting Islam or the Quran. The groups are insisting that the literal out-of-context interpretation of al-Maidah:51 is the only correct one. They take for granted that the verse literally prohibits non-Muslims from being a “leader” in a Muslim country.

The word auliya is not translated as “leader” in most contemporary translations as well as tafsir, the consequence of that translation is dangerous: non-Muslim ministers, regents, even bosses in companies where Muslims work are also leaders, aren’t they? Must they be dismissed from their positions just because of the verse?

The verse will only make sense if understood in its context, that is, in a situation of war, such as when the Jews were said to have betrayed the Muslims by violating the social contract made between the two to defend Medina together when the city-state was under attack; hence the later prohibition to make the Jews “allies” (the closest meaning to the word“auliya”).

Read more http://www.thejakartapost.com/

________________________

The writer is a graduate student at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS) at Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Corruption is one of many problems that Indonesia as a nation faces. It is not only a law-related problem but also a cultural problem. As such, culture and the values it promotes could also in one way or another be a powerful weapon to fight corruption. These are the points that Subandri Simbolon emphasized in his presentation about a ritual of sharing meat as a value to prevent corruption in Toba Batak society.

Corruption is one of many problems that Indonesia as a nation faces. It is not only a law-related problem but also a cultural problem. As such, culture and the values it promotes could also in one way or another be a powerful weapon to fight corruption. These are the points that Subandri Simbolon emphasized in his presentation about a ritual of sharing meat as a value to prevent corruption in Toba Batak society.

To begin his presentation, Subandri showed a video about the process of sharing meat (membagi jambar) ritual at a wedding in Batak land. The video tells about how the meat is shared to certain groups of families as a symbol of acknowledgment and appreciation of their existence. In the video, family members circle around the meat as it is being cut into specific portions and one person lifts up a portion of the meat and calls out family names and gives the meat to them as other people can watch them clearly. The portion of the meat is given out based on the Batak system of family kinship called Dalinan No Tolu..

The process of sharing jambar is arranged in some parts. First, mengalap ari. Mengalap ari is the process of choosing a good day to begin the ritual. Secondly, the ritual begins by cutting the meat into certain portions while the audience can see it clearly. The leader will then share the meat to the people by calling their names. Here is the strong educational point by the sharing meat ritual happened. By sharing the meat and let everyone watch it, it teaches people about honesty, appreciation and acknowledgment of the relationships among families. The meat being shared in jambar juhut is a representative of “source of life”. By receiving the source of life, people are receiving blessings. Other than being a symbol of blessing, meat also a symbol of people’s rights. When they receive their portion, it means their existence and their rights to be involved and participate are being acknowledged.. Therefore, discussing blessing and rights in the Toba Batak context invites people to not be greedy and to say enough when it is enough.

Subandri highlighted the point that in the process of sharing meat there are strong and meaningful interpretations where the generations can learn about anti-corruption attitudes. Moreover he added, in the ritual of jambar juhut there is a strong relational concept shows that humans are connected to each other. Because this cultural conception is to some extent closer to Batak Toba people’s daily lives than the abstract legal definitions of fairness and government laws, Subandri argued that it can be more effective and powerful to turn people from corruption. In a relational framework, corruption is an activity that is detrimental because it violates and even negatesrelationshipsReflecting on this relational framework, Subandri revisited the meaning of sharing meat in Toba Batak tradition, arguing that it can be interpreted as an effort to strengthen relationships and promote honesty.

During the discussion session there were many fascinating questions that led people to deeper reflection on how humans sometimes are separated from their tradition to such an extent that they no longer think of it as a part of their existence or as a medium to learn from but merely as ceremony. One challenging question was about how, in many other traditions, instead of fulfilling the intention of renewing people’s understanding about relationships, this kind of ritual fails because it becomes a problem because of economic reasons. In order to answer that, Subandri encouraged the audience to think about the meat as a symbol of source of life: if it feels burdensome, people can replace the meat with something else like vegetables so that no one will be excluded. Subandri was also asked about the role of Christianity as the major religion in Toba land in this kind of ritual. He answered that while sometimes a priest or pastor is invited to begin the ceremony with prayer, there is not really any significant influence.

The discussion came to an end with a challenging invitation for all of us to find in our own culture the values that we can use to develop a cultural defense against corruption. Even though there is always to the possibility we might misinterpret the meaning of rituals such as this one, in the end, it is worth trying.

Judul

Judul

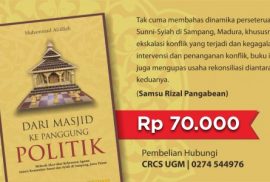

Dari Masjid ke Panggung Politik, Melacak Akar-akar Kekerasan Agama Antara Komunitas Sunni dan Syiah di Sampang, Jawa Timur

Penulis

Muhammad Afdillah

Penerbit

CRCS 2016

ISBN

978-602-72686-6-1

Harga

Rp 70.000,-

Beberapa aspek politik dan kekerasan Sunni-Syiah di Sampang dibahas di dalam buku ini. Salah satu di antaranya penyebab konflik antara komunitas Sunni dan Syiah di Sampang. Selain itu, buku ini membahas dinamika konflik Sunni-Syiah, khususnya eskalasi konflik yang terjadi seiring dengan berjalannya waktu dan kegagalan intervensi dan penanganan terhadap konflik tersebut. Buku ini juga membahas usaha – usaha rekonsiliasi kedua komunitas, khususnya setelah kekerasan terbuka yang terjadi di Bulan Desember 2011 dan Agustus 2012.

(Samsu Rizal Panggabean, Pengajar di Magister Perdamaian dan Resolusi Konflik di Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Universitas Gadjah Mada).

__________________________

Bagi yang tertarik, bisa menghubungi:

Divisi Marketing CRCS UGM

Gedung Lengkung Lantai 3

Sekolah Pascasarjana Universitas Gadjah Mada

Jl. Teknika Utara, Pogung, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 55281

Telephone/Fax : + 62-274-544976