Abstract

In many Muslim-majority societies,the widely accepted Islamic doctrine that men are to act as the ‘imam’ or leaders of the family lies at the bedrock of Muslim masculinity and male religious identity, but its meaning changes for Muslim men who live as a minority in liberal and increasingly secular societies such as Australia. Based on a sociological study of the issues and challenges facing Southeast Asian Muslim men living in Melbourne, I argue that the family does serve as a secure zone for preserving and exercising Islamic-associated practices of masculinity, but also that men are pressed to redefine the meaning and continually negotiate practices of leadership to cope with the demand for individual freedom and autonomy in the family as fits the much different social context. Finally, I call for more attention to the importance of masculinity as an analytical framework in religious studies.

Speaker

Rachmad Hidayat is a fellow and Project Director in the Kalijaga Institute for Justice, State Islamic University Sunan Kalijaga, a research associate at the Asia Institute, the University of Melbourne and previously was a visiting scholar at the Institute for Politics, Religions and Society, the Australian Catholic University. He earned a PhD in 2016 and MA in 2010 both at Monash University. Rachmad had worked at the State Islamic University Sunan Kalijaga as a project officer and research officer for programs fostering gender mainstreaming in religious contexts. His academic interests focus on how the discourse of masculinities and femininities sociologically shape and are shaped by dominant imbalance power relationship in families, institutions, academia, and religion. He has published Ilmu yang Seksis (Sexism in Sciences, Jendela 2004), Men’s Involvement in Reproductive Health, an Islamic Perspective, (with Hamim Ilyas, PSW 2006), some book chapters and journal articles about gender and masculinities.

CRCS

Kami sangat berterima kasih atas partisipasi para aplikan untuk mengikuti seleksi peserta Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragaman (SPK) angkatan ke-VIII yang diselenggarakan oleh Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies/CRCS, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta. Kami menerima banyak sekali aplikasi dari berbagai daerah di Indonesia dengan kualitas yang sangat kompetitif, dari beragam latar belakang profesi dan beragam isu yang diusung. Namun kami hanya memilih 25 orang peserta dengan mempertimbangkan berbagai aspek seperti: keragaman isu, gender, kemampuan melakukan riset, keterwakilan daerah, potensi membentuk jaringan advokasi, dan akses terhadap pengetahuan.

Abstract

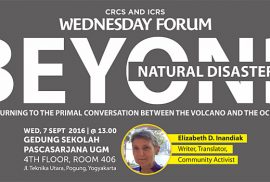

Scientists say that we have entered the Anthropocene, the era in which the influence of humankind on the many disasters on our earth is decisive. But ancient societies already understood disasters as a very complex and subtle interaction between the mood of man and the movement of nature. This is what we are reminded of by the Javanese tale Babad Ngalor-Ngidul, the title of which comes from a word we no longer understand: ngalor-ngidul. Composed of two Javanese words– lor for north and kidul for south plus the prefix ng that marks a back and forth movement–, ngalor-ngidul must have originally meant “from north to south and from south to north, in an endless burst of reciprocity and interdependence,” but now only means to talk nonsense. In the tale, the fates of the two villages, one in the south near the sea and one in the north near the volcano, are bound together as the former, destroyed by an earthquake, rebuilds itself, body and soul, while the latter becomes mentally corrupted before being devastated by a volcanic eruption. The tale is told in restore among the survivors the clarity of the “eye of the heart” that allowed the guardian of the volcano to “read” the mother-mountain and it reminds us that we must learn again to listen to the water of the ocean and to the sand of the volcano, the last speakers of a “primal” language that has existed since long before humankind.

Speaker

Elizabeth D. Inandiak is a writer, translator and community activist. Since the age of nineteen, she has traveled the world as a reporter for various French magazines and radio broadcasters. In 1989, she settled in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She has translated and recreated into French, Indonesian and English the great epic of Java: The Book of Centhini, published in Indonesian by Gramedia (Centhini – Kekasih yang Tersembunyi). Her new book Babad Ngalor Ngidul, (Gramedia) is a tale about the earthquake and the volcanic eruption in Yogyakarta. She is currently working on a book about Muara Jambi together with the young villagers of the site.

Daud Sihombing | CRCS | Article

Wilfred C. Smith in his book “The Meaning and the End of Religion,” defines reification as mentally making religion into a thing, gradually coming to conceive of religion as an objective systematic entity. In this process, religions are standardized and institutionalized. For instance, there were no “Hindus” who defined their practice as Hinduism until the term Hindu was established by Muslims and later British colonizers who invaded and sought to know and rule India. It was Muslims and Westerners with their concepts of religion who constructed or reified Hinduism.

Wilfred C. Smith in his book “The Meaning and the End of Religion,” defines reification as mentally making religion into a thing, gradually coming to conceive of religion as an objective systematic entity. In this process, religions are standardized and institutionalized. For instance, there were no “Hindus” who defined their practice as Hinduism until the term Hindu was established by Muslims and later British colonizers who invaded and sought to know and rule India. It was Muslims and Westerners with their concepts of religion who constructed or reified Hinduism.

Based on Smith’s insight, I am going to conduct an art exhibition which I call REIFICATION. In this exhibition I create an imaginary government institution named the Department of Certification. In my exhibition, this fictional governmental institution issues certificates for beliefs that fulfill the requirements to be recognized as a religion. My goals by conducting this exhibition are framing the religious discourse I learned in the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS), Universitas Gadjah Mada, in a different medium and offering new perspectives for seeing religious life in Indonesia.

This project can be considered a reflection of the past or the prediction for the future. What I mean by the reflection of the past is that I am going to visualize the unseen practice of standardizing the concept of religion and recognizing particular religions that happen in the past, especially in Indonesia. In predicting the future, I argue that this governmental institution can exist in Indonesia when the Bill of Rights protecting all religious people has been finalized.

This method of manipulating, imitating, pretending, or camouflaging in order to document an alternate reality has been used effectively by both Indonesian and foreign artists. An Indonesian artist, Agan Harahap created a photo series entitled The Reminiscence Wall, a compilation of “fictional novels” based on history that combines various realities of what happened in the past. Another example is Robert Zhao Renhui, a Singaporean multi-disciplinary artist. He constructs and layers each of his subjects with narratives, interweaving the real and the fictional. He focuses on the relation between humans and the natural world. Both Agan and Robert Zhao creates new “facts”based on their own fictional narratives.

This exhibition will be held in:

LIR Space, Yogyakarta, from September 3rd to 17th, 2016.

Open 12 pm – 20 pm, Closed on Monday.

It will be curated by Mira Asriningtyas as part of the ongoing Exhibition Laboratory project organized by Lir Space.

Suhadi | CRCS | Artikel

Akhir Juli 2016 lalu terjadi kekerasan di Tanjungbalai, Sumatera Utara. Sebagian sumber menyebutkan tidak kurang dari tiga vihara, delapan kelenteng, satu bangunan yayasan sosial dan tiga bangunan lain dirusak oleh massa. Terdapat enam mobil juga dirusak atau dibakar oleh massa.

Akhir Juli 2016 lalu terjadi kekerasan di Tanjungbalai, Sumatera Utara. Sebagian sumber menyebutkan tidak kurang dari tiga vihara, delapan kelenteng, satu bangunan yayasan sosial dan tiga bangunan lain dirusak oleh massa. Terdapat enam mobil juga dirusak atau dibakar oleh massa.

Kekerasan tersebut sangat patut disayangkan, meskipun demikian apresiasi kepada masyarakat Tanjungbalai dan aparat keamanan penting dikemukakan. Sebab, setidaknya kekerasan yang terjadi tidak meluas menjadi kekerasan horizontal lebih besar dalam jangka waktu yang panjang. Meskipun sudah terjadi agak lama, refleksi terhadap peristiwa kerusuhan tersebut tetap penting untuk meminimalisir kemungkinan berulangnya kekerasan sejenis, baik di Tanjungbalai ataupun di tempat lain.

Pendekatan Keamanan

Pada satu sisi, terjadinya pergerakan massa sampai merusak cukup banyak bangunan menunjukkan terlambatnya aparat keamanan bergerak melindungi warga dan patut menjadi catatan penting. Polisi seharusnya sudah bertindak cepat pada hari Jumat (29 Juli) malam itu, ketika massa dimobilisasi.

Di sisi lain, tindakan polisi, setelah kerusuhan terjadi, untuk melokalisir kerusuhan secara cepat, misalnya dengan menjaga keamanan wilayah dan memperketat keluar-masuk orang ke wilayah tersebut, patut diapresiasi. Dalam kasus-kasus kekerasan yang lain, tidak jarang aparat keamanan menjadi bagian dari masalah, atau setidaknya ragu-ragu, untuk dengan cepat mengambil keputusan bahwa kekerasan harus segera dihentikan. Pernyataan Kabid Humas Polda Sumut, Kombes Rina Sari Ginting, tidak lama setelah kerusuhan terjadi bahwa pelaku kekerasan melanggar pidana merupakan statemen yang jelas dan tegas bagaimana negara seharusnya hadir ditengah situasi yang genting.

Kerja bakti membersihkan puing-puing dan bekas kerusuhan yang dilakukan oleh aparat keamanan dan ratusan warga masyarakat Tanjungbalai sehari setelah kerusuhan terjadi dapat dimaknai sebagai isyarat publik bahwa situasi keamanan di Tanjungbalai dapat kembali normal dengan cepat. Ini penting disampaikan, karena dalam beberapa kejadian lain, ketika ketegasan aparat tidak tampak, apalagi jika ada upaya memanfaatkan situasi konflik untuk tujuan politik, situasi di suatu wilayah sulit untuk kembali normal.

Pendekatan Dialog untuk Perdamaian

Kerusuhan Tanjungbalai bukan pertama kali terjadi di daerah tersebut. Sebelumnya, kerusuhan serupa pernah terjadi pada tahun 1979, 1989, dan 1998 (Komnas HAM 2016). Artinya, meskipun dalam kehidupan sehari-hari berlangsung praktik koeksistensi di masyarakat, potensi konflik bisa berkembang dan pada momen-momen tertentu meledak menjadi kekerasan massa.

Oleh sebab itu, pendekatan keamanan saja tidak akan memadai. Dialog antar kelompok di masyarakat menjadi niscaya dibutuhkan. Dalam konteks masyarakat Tanjungbalai, dialog tersebut mungkin bisa kita sebut dialog multikultural untuk perdamaian.

Disebut dialog multikultural sebab tidak saja menyangkut agama, tetapi juga etnik. Seperti ditunjukkan kasus Tanjungbalai, seorang warga berketurunan Tionghoa, berusia 41 tahun, yang memprotes nyaringnya pengeras suara adzan di samping rumahnya, menyulut diserangnya rumah ibadah umat Khonghucu dan umat Buddha.

Disebut untuk perdamaian karena fokus atau tujuan utamanya adalah perdamaian. Tidak semua dialog memiliki tujuan perdamaian secara langsung. Sebut saja, salah satu contohnya dialog teologis, seperti dialog antar ahli kitab suci agama-agama. Meskipun bisa juga mengarah pada perdamaian, dialog teologis bisa mengarah pada pengayaan teologis an sich dan tidak memiliki pengaruh langsung pada aspek sosial di masyarakat.

Jika kita mengikuti perkembangan wacana antar etnik pasca kerusuhan Tanjungbalai yang berkembang di media, terutama di media sosial, sangat jelas bahwa prasangka antar etnik berkembang luas dan mendalam. Diantara karakter prasangka adalah persepsi negatif dan generalisasi-berlebih (Suhadi & Rubi 2012, konsep tentang prasangka bisa dibaca dalam salah satu artikel buku Kajian Integratif Ilmu, Agama dan Budaya atas Bencana).

Persepsi negatif terhadap suatu kelompok etnik atau agama tertentu, apalagi jika mendapatkan dukungan dari praktik orang-orang dalam komunitas bersangkutan, pada gilirannya dapat berkembang menjadi legitimasi yang efektif untuk meminggirkan, menyerang atau menghancurkan kelompok yang dianggap memiliki perilaku negatif itu. Dukungan fakta praktik negatif tersebut bisa saja ditemukan hanya pada satu-dua orang, atau dalam jumlah lebih besar tetapi terbatas. Di sini terjadi proses transformasi dari identifikasi individu ke identifikasi kelompok.

Lebih-lebih karena bekerjanya prasangka juga bersifat generalisasi-berlebih, maka seringkali sasaran kekerasan yang mengandung unsur prasangka dapat mengenai anggota komunitas yang lebih luas. Bahkan, korban kekerasan bisa jadi adalah orang-orang yang tidak setuju atau menentang sikap negatif dari anggota komunitasnya.

Hal inilah yang persis terjadi di Tanjungbalai. Tindakan satu orang disambut dengan balasan kekerasan yang luas kepada komunitas etnik dan agama yang dianggap memiliki kesamaan identitas. Kekerasan seperti itu tentu tidak sekonyong-konyong terjadi. Sebelumnya berkembang prasangka yang mungkin telah meluas dan mendalam di masyarakat. Penting diingat bahwa pada tahun 2010 telah muncul keresahan terkait dengan upaya penurunan patung Buddha di Tanjung Balai. Peristiwa itu seharusnya sudah menjadi pengingat bahwa ada hubungan sosial yang harus diperbaiki di sana (lihat, misalnya tribunnews.com dan blasemarang.kemenag.go.id)

Agar tidak terulang kembali, kekerasan dan konflik seperti itu tidak bisa dipulihkan hanya dengan pendekatan keamanan. Dialog di tingkat masyarakat menjadi prasyarat penting proeksistensi yang berkelanjutan di Tanjungbalai.

Abu-Nimer (2000) dalam sebuah tulisannya dengan judul “The Miracle of Transformation through Interfaith Dialogue” menyebutkan dialog merupakan alat yang sangat menolong untuk memperdalam pemahaman individu mengenai berbagai cara pandang dan perspektif orang lain.

Dalam masyarakat yang menyimpan ketegangan relasional, mereka mesti membangun dulu sikap saling percaya (trust). Baru setelah itu masing-masing kelompok dapat membicarakan keberatan-keberatan yang dirasakan masing-masing dalam praktik kehidupan sehari-hari mereka. Alih-alih merasa tidak ada masalah, lebih baik dalam dialog mengakui dengan jujur masalah-masalah yang ada selama ini menjadi prasangka.

Pada praktiknya tentu ini tidak mudah. Membangun sikap saling percaya untuk mengungkapkan masalah-masalah yang ada perlu proses panjang, lebih dari satu-dua kali pertemuan bersama. Namun jika hal itu dapat dilampaui, kesepakatan-kesepakatan relasional bisa mulai dirumuskan bersama.

Lebih dari itu, dialog dapat berkembang menjadi kerjasama kongkrit antar kelompok, menyangkut hal sehari-hari terkait, misalnya, masalah lingkungan, kesehatan, kepemudaan, penyelenggaraan festival bersama atau hal lain.

Untuk memperkuat bahwa dialog merupakan kebutuhan yang tumbuh dari komunitas antar kelompok di masyarakat lokal Tanjungbalai sendiri, nilai-nilai agama dan nilai-nilai budaya lokal yang tumbuh di mayarakat penting menjadi panduan bersama. Sejarah lokal di Tanjungbalai menunjukkan keberadaan etnik Batak, Melayu, Tionghoa, Jawa, dan yang lain telah hidup bersama dalam waktu sangat lama. Dalam pengalaman hidup bersama mereka pasti terdapat best practices nilai-nilai dan praktik-praktik kerjasama yang dapat dijadikan pelajaran, baik yang masih terus berlangsung maupun yang perlu digali untuk dihidupkan kembali.

Dialog dan kerjasama bisa jadi mendapat penentangan dari pihak tertentu di masyarakat. Sebab mungkin saja ada pihak-pihak dalam masyarakat yang berkepentingan dengan konflik.Untuk itu pemerintah dan aparat keamanan penting memberi jaminan rasa aman bagi proses berlangsungnya dialog dan kerjasama tersebut. Dialog yang lebih genuine sebaiknya melibatkan masyarakat akar rumput, meskipun keberadaan tokoh agama dan tokoh masyarakat juga tidak bisa diabaikan. Memulainya dengan kaum muda mungkin menjadi pilihan yang lebih mudah dan realistis.

__________________

Suhadi adalah dosen di Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga. Di samping itu juga mengajar di Prodi Agama dan Lintas Budaya, Sekolah Pascasarjana UGM. Suhadi adalah juga Southeast Asia KAICIID fellow untuk program dialog antaragama dan dialog antar budaya.

Maria Lichtmann | CRCS | Article

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”13″] “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”13″] “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.”

-CRCS’ Student- [/perfectpullquote]

Teaching the course on “Religion, Women, and the Literatures of Religion” was one of the highlights of my teaching career. From the first day, when I stepped into the classroom and was greeted with smiles and welcomes, I knew I could feel comfortable bringing what I knew and wanted to teach to these students. This class of students had already been seasoned and prepared to be a community of learners by having studied the better part of the year in this unique program. I did not detect the kind of competitive edge that is so much a feature of classroom interaction in the United States, and I feel that has something to do with the culture here of long-standing collaboration and sharing. It was certainly evident in the way these students worked together, laughed together, and enjoyed time after class, such as in “buka puasa,” the opening of the fast that comes during Ramadhan. Coming from various parts of this vast country, from Medan on the island of Sumatra, from Aceh, from the small island of Lombok, as well as many cities around Java, they also represented diverse religious backgrounds, the majority Muslim, but also Protestant Christian and Catholic Christian (the one Catholic being a Sister of Notre Dame whom the students had come to see as “ibu,” Mother). About three-fourths of the students were male, and although that might have seemed an impediment to learning almost the entire semester only about women, these young men showed no signs of resistance, and in fact demonstrated an amazing openness and willingness to engage the issues confronting women in the Midldle Ages as well as today.

What was just as impressive to me was that they were reading and writing academic studies in English, a discourse that can be difficult even for native speakers! They stretched themselves in so many ways that it was truly admirable, and I know many of them struggled. Despite that, they produced response papers that were for the most part readable and intelligent, some brilliant. I heard so many new insights from their unique perspectives, and they helped me to look at these works by medieval and modern women with new eyes.

The content of the course consisted primarily of writings from Christian mystics and visionaries of the Middle Ages, as well as a thesis written on Sufi women mystics. We encountered the remarkable prison diary of St. Perpetua, martyred in 203 C.E., and marveled over the multi-talented abbess, musician, poet, prophet, mystic, Hildegard of Bingen, discussed food in the writings of the unique medieval women’s group, the Beguines, and then focused on the book, Showings, written by Julian of Norwich. I would like to include here some of the comments students made when reading her beautiful treatise, to give some idea of how open they were to learning across boundaries of time, gender, and theology:

“Her style of contemplating God is set in the fourteenth century, but the meaning is still alive and meaningful today and invites us to share in that same trustworthy love. “

“Showings reveals a woman who experienced God directly and as “our mother.”

“Her revelations of the feminine side of God are a very significant contribution to all of us now.”

“God’s grace and divine love through a feminine figure is such an empowerment and encouragement for all beings, not only women. Also men, because the feminine qualities show how simply love can comfort and heal, just like a mother’s love.”

“The dualism of feminine/ masculine no longer exists in Julian’s understanding of God. God is feminine, and at the same time also masculine. The human/body and the divine, the feminine and masculine, each of both is actually a union.”

I was very happy to have CRCS’ alumna, Najiyah Martiam’s Master’s Thesis on Sufi women, based on her interviews with three women connected to pesantrens, in order to balance what could have been an over-emphasis on the Christian tradition, the one I know best. We also had a chance to invite another CRCS alumna, Yulianti, a Buddhist scholar who happens to be a friend of mine. Yuli helped explain how the female lineage in Theravada Buddhism died out, and has not been restored because the line was broken.

I was very happy to have CRCS’ alumna, Najiyah Martiam’s Master’s Thesis on Sufi women, based on her interviews with three women connected to pesantrens, in order to balance what could have been an over-emphasis on the Christian tradition, the one I know best. We also had a chance to invite another CRCS alumna, Yulianti, a Buddhist scholar who happens to be a friend of mine. Yuli helped explain how the female lineage in Theravada Buddhism died out, and has not been restored because the line was broken.

Two of the most exciting, energizing classes were led Dewi Chandraningrum, the editor of Jurnal Perempuan (Indonesian Feminist Journal), who brought us readings from her edited volume, Body Memories. I was very happy to have Bu Dewi’s presence in the classroom, and to see the student’s immediate warm responses to her as she sometimes spoke in Bahasa Indonesia, the language most accessible for them. In her first class, she divided the students into three groups, in discussion of three topics relating to the female body: menstruation, sexual intercourse, and childbirth. What could have been a class of silence, embarrassment, or even giggles, became a serious, mature conversation among the students. I was awed by their willingness to discuss such sensitive topics together, with mixed genders. Bu Dewi’s second class introduced us to the women activists of Kartini Kendeng, and the opposition to the proposed cement factory that has already decimated villages and their way of life in northern Java.

I would like to say in conclusion, that based on the readings from the women mystics like Julian of Norwich, whose theology of the body is holistic, non-dualist, and healthy, and intensified in the sessions led by Bu Dewi, this class became almost a spirituality of the body. Sacred sexuality and the sacredness of the female body became an underlying theme. I will let one of the students have the last word by quoting from his final paper: “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.” This student and others showed me at what depth of understanding they were interpreting what they read and heard. They were a gift and joy to teach!

____________________________

Maria Lichtmann is a Fulbright fellow to Indonesia. She taught “Women, Religion, and Literatures” in intersession semester at CRCS from June to July, 2016. She is a former professor of Religious Studies at ASU and currently teaching at Widya Sasana, Malang.