A student's reflection on the Talentime movie watched in the CRCS's Religion and Film course.

religion

Jonathan D Smith | CRCS | Essay

Indonesia is home to many environmental movements, either led by established environmental activists or by groups of indigenous people. The reclamation project in Benoa Bay, cement mining in Kendeng area, Central Java, and the Save Aru movement are just a few recent examples. Does religion play a role in these movements? Are these local movements related to the growing global environmental movement?

The local and global is a crucial element of environmental movements, because environmental problems defy boundaries. Our rapidly-changing climate poses an urgent challenge that is both global and local. As national governments slowly acknowledge their role in reducing carbon emissions (with some exceptions), local communities in Indonesia are living with the problems of rising temperatures and sea levels, increases in natural disasters, and increasing pollution of our air and water.

Local-global connections in religious environmental movements

In 2016 at the climate summit in Morocco, governments met to affirm their adoption of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Signed by 111 countries (as of November 2016), the agreement commits to reducing carbon emissions and recognizes the human impact on climate change. At the same climate summit in Marrakech, hundreds of religious leaders and environmental activists launched the Interfaith Climate Statement.

The Interfaith Climate Statement included these words:

Anang G Alfian | CRCS | News

Universitas Gadjah Mada’s Faculty of Biology invited Whitney Bauman to present his on-going project at the Biology Hall on Monday, March 6th, 2017. Students and lecturers from various faculties came to hear his lecture. His specialization on the discourse of religion, science, and nature reflects his capacity as an associate professor at the Department of Religious Studies, Florida International University, as well as author of works including Theology, Creation, and Environmental Ethics (Routledge 2009) and Religion and Ecology: Developing a Planetary Ethics (2014). A longtime friend of CRCS who has taught intersession courses more than once, he is currently working to finish his third, single-authored book with a tentative title Truth, Beauty and Goodness: Ernst Haeckel and Religious Naturalism.

In his lecture, introduced by paleontology lecturer Donan Satria Yudha as the moderator, Bauman engaged religion and science in a contemporary discussion to look for a new way of understanding each through an evolutionary perspective. This perspective of religion-science relationship was inspired by the contemporary phenomenon in which religion has gained more spaces within science.

The emphasis Bauman made in the beginning of the lecture pointed out the direction of his topic of presentation. He started how historically the notion of religion has been discussed by different perspectives from dualism and reductionism to emergence theory. Along with the continuum of religion-science relationship, he challenged to look at the relation in a new way by focusing on the German scientist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) who formulated a new way of making sense out of the world through his studies of ecology and evolution. Bauman clearly stated his stance: “to place Haeckel’s Monism in continuity with this tradition of meaning-making.” He also emphasized that everything has undergone changes and the way we understand the relation between religion and science has always been a “relationship in constant flux.” He challenged the assumption of the previous models on religion-science relationship that views Religion and Science as two different traditions. “I argue that Religion and Science are always together, influencing one another,” Bauman continued, “there is no clear separation.”

As Bauman prefers to define “religion” through its meaning-making function, he observed that the way religion attains knowledge is also inseparable from the natural evolution perspective. Further, he explained that the relation involves not only human and nature as a traditional dichotomy but more as an interconnectedness of everything. This view triggered questions from the audience.

One member of the audience asked a question on a human special status over the rest of nature which challenged the way certain traditions or religions view the status of humans in their scriptures. “I am not sure if humans have a special status in nature,” Bauman answered, “In fact, not only humans have culture and language; many other creatures might have them too.” Because knowledge is always in process and moves together with history and experiences, he argued that it is normal for many traditions to have different understandings of nature and the Truth.

Another question posed was about whether the first human walking on earth was the one as narrated in the scripture. Baumann referred to “Adam” as mentioned in the Genesis as its literal meaning, i.e. a creature on the earth which did not refer to any specific gender. In addition, Donan Satria Yudha said that some Muslim scientists say that Homo sapiens may constitute the first human as mentioned in the scripture and it refers to the quality of being human in the evolution, and not to a specific figure.

The writer, Anang G Alfian, is CRCS student of the 2016 batch

Abstract:

In this discussion, Jonathan Zilberg will discuss problems fracing Indonesian museum in terms of performance, accountability and transparency. He will discuss the Goverment of Indonesia’s 2010-2014 museum revitalization program, the transformations that have been taking place in Indonesia museum over the last decade and the challenges posed for the future. He will look at museums as democracy machines and as postcolonial centers for advacing the ideology of pluralism in civil society. In particular he will address the integrated importance of museums, adchives and libraris for advacing the state of education at all levels including for countinuing adult education.

Speaker:

Jonathan Zilberg is a cultural anthropologist specializing in art and religion and in museum ethnography. He has been studying Indonesian museums for a decade and is particularly interested in museums as democracy machines and as post-colonial centers for advancing the ideology of pluralism in civil society. His immediate interests focus on Hindu-Buddhist heritage including the function of archaeological sites as open air museums as well as of museum collections and government depositories in terms of being under-utilized academic resources. For comparative purposes, he has studied museums in Aceh, Jambi, Jakarta and to a lesser extent observed select museums elsewhere in Indonesia. Currently he is CRCS UGM Visiting Scholar.

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Class Journal

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

As an American lecturer who has been working with CRCS since 2014 through Eastern Mennonite University, Virginia, he is a very well-experienced educator as he previously spent some years teaching in Japan. Moreover, his interest in following up the up-dated global issues including religious nuances, made him familiar with framing the methods of studying religion and globalization.

Global ethics is one of the topics we discussed in the class, the last material before the end of the class. Previously, we talked a lot about globalization as a phenomenon affecting religions as well as several religious responses toward globalization. Despite the supporters of globalization, many religions seem to fearfully reject it, some even proclaiming their resistance and becoming more radical.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Therefore, to foster the stabilization of the world order from war and disputes, it is necessary to rethink globalization in ways that are more ethical and friendly to the world. On the topic discussion of global ethics, we learned about attempts by world organizations like the United Nations in generating international agreements including the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Besides, other agreements such as the Cairo and Bangkok Declarations represent local voices which to some points define human rights differently.

The difference in worldviews among international actors is interesting because each organization tries to define a global value within their own relativities. Moreover, some theories think that UN Declaration on Human Right is a Western domination over other cultures without considering cultural relativities, including religions, each of which inherits different theological and structures while at the same time sharing common values like peace, humanity, equality, and justice.

World issues indeed became valuable perspective in this class. Students are meant to not only understand theories but also keep updating their knowledge on what is happening in the recent international world. While negative influences of globalization such as war, religious radicalization, and other world disputes were discussed in the class, there is also a hope for a global agreement and bright future by sharing noble values like cooperation, justice, human dignity, and peace on global scale. The existence of world organizations and religious representatives in fostering global ethics proves the progress made towards creating world peace. The duty of students, in this case, is to contribute academically to spreading such values without neglecting the variety of cultural and religious perspectives.

*The writer is CRCS’s student of the 2016 batch.

Anang G. Alfian* | CRCS | Class Journal

Salah satu mata kuliah yang diajarkan di CRCS adalah Religion, Violence, and Peace Building (Agama, Kekerasan, dan Perdamaian). Tiga kata kunci ini menjadi variabel dan titik tolak diskusi tentang hubungan agama dan konflik sosial dan bagaimana upaya untuk membangun perdamaian.

Diampu oleh Dr. Iqbal Ahnaf, mata kuliah ini membahas, antara lain, persoalan relasi antara agama dan konflik. Ini dibahas di pertemuan pertama untuk membuka wawasan tentang perdebatan yang terjadi mengenai hubungan kausalitas antara agama dan kekerasan.

Pada pertemuan ini, satu dari dua bacaan yang dipakai sebagai bahan readings adalah artikel dari Andreas Hasenclever dan Volker Rittberger, Does Religion Make a Difference?: Theoretical Approaches to the Impact of Faith on Political Conflict (Journal of International Studies, 2000).

Dalam artikel itu, Hasenclever dan Rittberger memaparkan tiga mazhab dalam dunia akademik dalam membaca hubungan agama dan konflik, yaitu (1) primordialis, (2) instrumentalis, dan (3) konstruktivis.

Kaum primordialis berpandangan bahwa agama dalam dirinya sendiri memiliki unsur inheren yang dapat menyebabkan konflik. Ketika terjadi “konflik agama”, agama dibaca oleh kaum primordialis sebagai variabel yang independen, unsur yang tidak bergantung pada aspek-aspek lain, dan perbedaan identitas keagamaan itu sendiri bisa cukup sebagai penyebab konflik.

Kaum instrumentalis melihat peran agama dalam “konflik agama” sebagai instrumen saja, dan tidak memiliki peran objektif dalam dirinya sendiri. Menurut kaum instrumentalis, penyebab utama konflik adalah kepentingan politik dan ekonomi. Bagi kaum instrumentalis, agama hanya berperan dalam retorika saja, dan relasinya dengan konflik bersifat semu belaka.

Kaum konstruktivis tampak berada di tengah-tengah antara kedua kelompok di atas. Konstruktivis bersetuju dengan instrumentalis dalam hal bahwa penyebab fundamental konflik bukanlah agama, melainkan kepentingan politik dan ekonomi. Namun konstruktivis juga bersepakat dengan primordialis dalam hal bahwa agama memiliki peran nyata objektif, namun bukan sebagai penyebab utama, melainkan eskalator konflik. Agama, ketika terlibat dalam konflik, dapat membuat konflik semakin mematikan, deadly. Juga, berbeda dari primordialis yang berpandangan bahwa agama menjadi variabel independen dalam konflik, bagi kaum konstruktivis agama berperan secara dependen, tergantung pada faktor-faktor ekonomi dan politik lain yang melingkupi konflik tersebut; seberapa besar peran agama mengeskalasi konflik tergantung pada seberapa akut benturan antar kepentingan politik dan ekonomi dalam konflik itu.

Ketiga cara pandang di atas tidak bisa diperlakukan secara universal. Tapi ketiganya bisa dijadikan lensa analitis dan ditempatkan dalam suatu spektrum. Bagaimana menentukan peran agama dalam suatu konflik mestilah dimulai dari detil kasus konfliknya, lalu naik melihat lensa-lensa analitis yang ada, kemudian menentukan di antara yang tersedia manakah penjelasan yang lebih tepat.

Dalam “kasus Sunni-Syiah” Sampang, misalnya, dimensi konflik yang terjadi bukan hanya karena faktor perbedaan ideologis semata, namun juga karena adanya instrumentalisasi agama oleh elite politik, karena konflik ternyata bereskalasi pada masa perebutan kekuasaan menjelang pemilu daerah, sehingga narasi-narasi agama di legitimasi sedemikian rupa untuk suatu tujuan politik. Dalam melihat hal ini, kita tak bisa berhenti pada pandangan kaum primordialis—inilah pandangan yang diadopsi oleh mereka yang memercayai bahwa konflik Sampang itu adalah konflik Sunni-Syiah. Dimensi sosial politik dalam konflik itu wajib dihitung, mulai dari yang kecil seperti persengkataan internal keluarga, perebutan umat, hingga yang lebih makro seperti instrumentalisasi konflik untuk mendulang dukungan dalam pemilu.

Dalam perspektif konstruktivis, intervensi terhadap konflik dengan menyuarakan nilai-nilai kebajikan agama, kearifan lokal, dan slogan-slogan orang Madura Sampang sangat membantu upaya rekonsiliasi konflik, yakni untuk melakukan deskalasi terhadap konflik itu dengan mengajukan narasi tandingan primordialis. Penelitian Dr. Iqbal Ahnaf beserta peneliti yang lain dalam serial laporan CRCS tentang kehidupan beragama di Indonesia yang bertajuk Politik Lokal dan Konflik Keagamaan menunjukkan instrumentalisasi agama oleh elit politik di Sampang menjelang pilkada. Tesis S2 terkait kasus Sampang ini juga ditulis oleh mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2010 Muhammad Afdillah yang kini telah dijadikan buku dengan judul Dari Masjid ke Panggung Politik.

Kasus Sampang merupakan contoh yang bagus untuk membaca seberapa besar peran agama dalam konflik, dan ini membutuhkan data dan analisis yang cermat. Contoh-contoh lain dari yang terjadi di Indonesia yang bisa diambil ialah kasus Ambon dan Poso, atau yang belum lama ini terjadi seperti di Tolikara, Tanjungbalai, atau bahkan kasus dugaan “penodaan agama” dalam pilkada Jakarta.

*Penulis adalah mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2016

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Quoting the great French novelist Victor Hugo’s remark that “Life is a compilation of stories written by God” Inandiak highlighted how meaning is found in stories which come before larger systems like religion. In her book and her talk, she told stories from her experiences with the victims of natural disasters in two communities, one, Kinahrejo, in the North and one, Bebekan,in the South. Inandiak explained that the process of recovery after a natural disaster is a process with and within the nature. It is about the reconciliation between human communities and nature. In natural disasters people mostly lose their belongings such houses, money, clothes and domesticated animals, but, she said, the most important thing is not to lose their identity. Houses can be rebuilt, but once people lose identity they don’t know how to rebuild anything else. Inandiak spoke about the disaster as a conversation between the North and the South. This is also a kind of stories that helps people deal with their situation, by accepting that disaster are part of natural cycles.

Inandiak also spoke about rituals. First there were the rituals enacted by Mbah Maridjan and Ibu Pojo, the shamaness who was his unacknowledged partner, to connect human communities and nature. The offering ritual they made to Merapi included three important layers that describes their own identities: ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam especially Sufism. Despite all the issues that Mbah Marijan and Ibu Pojo faced before they died in the 2010 eruption, they insisted what they were doing is an act of communicating with the nature that was their home. Second, in order to overcome the difficulties after a disaster, stories and ritual mean a lot for reestablishing the victims’ identity. By doing rituals like dancing or singing, they connect to the wishes that become true. The wishes that they made bring such a different in their perspectives in continuing life. Through ritual people want to get connected with nature and Inandiak told how she helped these villages rebuild their identities.

In the question and answer session, we were moved by many fascinating question about the relation of nature and person. One of them is how the three layers in Javanese ritual—reverence for ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam, particularly Sufism—deal with the interference of world religion. Inandiak responded that there must be many changes brings by the world religion, especially in Kinahrejo, where Mbah Maridjan faced pressure from fundamentalists. The way villagers perceive myth changes from time to time. Their Muslim-Javanese identity is something they need to maintain in negotiation. In answering the issues about participants in the rituals wearing hijab, Inandiak argued that these layers should be clearer. They are not rooted in one story. But to maintain the customs is also important.

Inandiak closed her presentation with a remarkable message that disasters come from the interaction of people and nature but no one should feel guilty or think that any disaster is the result of sin or human mistakes. The most important things are not to give up and to work to rebuild identity.

Daud Sihombing | CRCS | Article

Wilfred C. Smith in his book “The Meaning and the End of Religion,” defines reification as mentally making religion into a thing, gradually coming to conceive of religion as an objective systematic entity. In this process, religions are standardized and institutionalized. For instance, there were no “Hindus” who defined their practice as Hinduism until the term Hindu was established by Muslims and later British colonizers who invaded and sought to know and rule India. It was Muslims and Westerners with their concepts of religion who constructed or reified Hinduism.

Wilfred C. Smith in his book “The Meaning and the End of Religion,” defines reification as mentally making religion into a thing, gradually coming to conceive of religion as an objective systematic entity. In this process, religions are standardized and institutionalized. For instance, there were no “Hindus” who defined their practice as Hinduism until the term Hindu was established by Muslims and later British colonizers who invaded and sought to know and rule India. It was Muslims and Westerners with their concepts of religion who constructed or reified Hinduism.

Based on Smith’s insight, I am going to conduct an art exhibition which I call REIFICATION. In this exhibition I create an imaginary government institution named the Department of Certification. In my exhibition, this fictional governmental institution issues certificates for beliefs that fulfill the requirements to be recognized as a religion. My goals by conducting this exhibition are framing the religious discourse I learned in the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS), Universitas Gadjah Mada, in a different medium and offering new perspectives for seeing religious life in Indonesia.

This project can be considered a reflection of the past or the prediction for the future. What I mean by the reflection of the past is that I am going to visualize the unseen practice of standardizing the concept of religion and recognizing particular religions that happen in the past, especially in Indonesia. In predicting the future, I argue that this governmental institution can exist in Indonesia when the Bill of Rights protecting all religious people has been finalized.

This method of manipulating, imitating, pretending, or camouflaging in order to document an alternate reality has been used effectively by both Indonesian and foreign artists. An Indonesian artist, Agan Harahap created a photo series entitled The Reminiscence Wall, a compilation of “fictional novels” based on history that combines various realities of what happened in the past. Another example is Robert Zhao Renhui, a Singaporean multi-disciplinary artist. He constructs and layers each of his subjects with narratives, interweaving the real and the fictional. He focuses on the relation between humans and the natural world. Both Agan and Robert Zhao creates new “facts”based on their own fictional narratives.

This exhibition will be held in:

LIR Space, Yogyakarta, from September 3rd to 17th, 2016.

Open 12 pm – 20 pm, Closed on Monday.

It will be curated by Mira Asriningtyas as part of the ongoing Exhibition Laboratory project organized by Lir Space.

Maria Lichtmann | CRCS | Article

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”13″] “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=”13″] “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.”

-CRCS’ Student- [/perfectpullquote]

Teaching the course on “Religion, Women, and the Literatures of Religion” was one of the highlights of my teaching career. From the first day, when I stepped into the classroom and was greeted with smiles and welcomes, I knew I could feel comfortable bringing what I knew and wanted to teach to these students. This class of students had already been seasoned and prepared to be a community of learners by having studied the better part of the year in this unique program. I did not detect the kind of competitive edge that is so much a feature of classroom interaction in the United States, and I feel that has something to do with the culture here of long-standing collaboration and sharing. It was certainly evident in the way these students worked together, laughed together, and enjoyed time after class, such as in “buka puasa,” the opening of the fast that comes during Ramadhan. Coming from various parts of this vast country, from Medan on the island of Sumatra, from Aceh, from the small island of Lombok, as well as many cities around Java, they also represented diverse religious backgrounds, the majority Muslim, but also Protestant Christian and Catholic Christian (the one Catholic being a Sister of Notre Dame whom the students had come to see as “ibu,” Mother). About three-fourths of the students were male, and although that might have seemed an impediment to learning almost the entire semester only about women, these young men showed no signs of resistance, and in fact demonstrated an amazing openness and willingness to engage the issues confronting women in the Midldle Ages as well as today.

What was just as impressive to me was that they were reading and writing academic studies in English, a discourse that can be difficult even for native speakers! They stretched themselves in so many ways that it was truly admirable, and I know many of them struggled. Despite that, they produced response papers that were for the most part readable and intelligent, some brilliant. I heard so many new insights from their unique perspectives, and they helped me to look at these works by medieval and modern women with new eyes.

The content of the course consisted primarily of writings from Christian mystics and visionaries of the Middle Ages, as well as a thesis written on Sufi women mystics. We encountered the remarkable prison diary of St. Perpetua, martyred in 203 C.E., and marveled over the multi-talented abbess, musician, poet, prophet, mystic, Hildegard of Bingen, discussed food in the writings of the unique medieval women’s group, the Beguines, and then focused on the book, Showings, written by Julian of Norwich. I would like to include here some of the comments students made when reading her beautiful treatise, to give some idea of how open they were to learning across boundaries of time, gender, and theology:

“Her style of contemplating God is set in the fourteenth century, but the meaning is still alive and meaningful today and invites us to share in that same trustworthy love. “

“Showings reveals a woman who experienced God directly and as “our mother.”

“Her revelations of the feminine side of God are a very significant contribution to all of us now.”

“God’s grace and divine love through a feminine figure is such an empowerment and encouragement for all beings, not only women. Also men, because the feminine qualities show how simply love can comfort and heal, just like a mother’s love.”

“The dualism of feminine/ masculine no longer exists in Julian’s understanding of God. God is feminine, and at the same time also masculine. The human/body and the divine, the feminine and masculine, each of both is actually a union.”

I was very happy to have CRCS’ alumna, Najiyah Martiam’s Master’s Thesis on Sufi women, based on her interviews with three women connected to pesantrens, in order to balance what could have been an over-emphasis on the Christian tradition, the one I know best. We also had a chance to invite another CRCS alumna, Yulianti, a Buddhist scholar who happens to be a friend of mine. Yuli helped explain how the female lineage in Theravada Buddhism died out, and has not been restored because the line was broken.

I was very happy to have CRCS’ alumna, Najiyah Martiam’s Master’s Thesis on Sufi women, based on her interviews with three women connected to pesantrens, in order to balance what could have been an over-emphasis on the Christian tradition, the one I know best. We also had a chance to invite another CRCS alumna, Yulianti, a Buddhist scholar who happens to be a friend of mine. Yuli helped explain how the female lineage in Theravada Buddhism died out, and has not been restored because the line was broken.

Two of the most exciting, energizing classes were led Dewi Chandraningrum, the editor of Jurnal Perempuan (Indonesian Feminist Journal), who brought us readings from her edited volume, Body Memories. I was very happy to have Bu Dewi’s presence in the classroom, and to see the student’s immediate warm responses to her as she sometimes spoke in Bahasa Indonesia, the language most accessible for them. In her first class, she divided the students into three groups, in discussion of three topics relating to the female body: menstruation, sexual intercourse, and childbirth. What could have been a class of silence, embarrassment, or even giggles, became a serious, mature conversation among the students. I was awed by their willingness to discuss such sensitive topics together, with mixed genders. Bu Dewi’s second class introduced us to the women activists of Kartini Kendeng, and the opposition to the proposed cement factory that has already decimated villages and their way of life in northern Java.

I would like to say in conclusion, that based on the readings from the women mystics like Julian of Norwich, whose theology of the body is holistic, non-dualist, and healthy, and intensified in the sessions led by Bu Dewi, this class became almost a spirituality of the body. Sacred sexuality and the sacredness of the female body became an underlying theme. I will let one of the students have the last word by quoting from his final paper: “Women’s bodies can be very good when interpreted as fertility, mercy, and wisdom, but they can also be interpreted as objects attracting sexual desire or even worse as spiritually less than men. . . . The narration of Hawa (Eve) and Sri (Javanese goddess figure) could be seen from any point of view, depending on our intention. Yet, perceiving that male is more spiritual than woman by nature is not only male centrist, but also discriminating over the other and shows how arrogant it is.” This student and others showed me at what depth of understanding they were interpreting what they read and heard. They were a gift and joy to teach!

____________________________

Maria Lichtmann is a Fulbright fellow to Indonesia. She taught “Women, Religion, and Literatures” in intersession semester at CRCS from June to July, 2016. She is a former professor of Religious Studies at ASU and currently teaching at Widya Sasana, Malang.

A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Interview

Sejak tahun 2015, Dr. Kimura Toshiaki, associate professor Program Studi Agama, Universitas Tohoku, Sendai, Jepang menjadi salah satu pengajar mata kuliah ‘Sains, Agama dan Bencana’ di Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (CRCS), UGM. Membincang bencana di Jepang sangat menarik karena Jepang adalah negara dengan kesiapan bencana yang sangat tinggi. Menjadi lebih menarik ketika memasukkan agama dalam perbincangan bencana di negeri Sakura itu. Bencana adalah sesuatu yang sangat akrab bagi masyarakat Jepang, tapi agama? Sesuatu yang dihindari pada awalnya tapi perlahan diterima karena bencana. Berikut wawancara tim CRCS dengan dosen yang akrab dipanggil Kimura Sensei ini mengenai bencana, agama, dan studi agama di Jepang.

Kimura Sensei, bagaimana masyarakat Jepang memahami relasi antara agama, bencana, dan sains?

Mayoritas orang Jepang menganggap persoalan bencana ini hanya seputar sains, material, medis atau teknologi belaka. Namun menurut saya, bencana juga memiliki nilai-nilai agama, dan agama dapat membantu orang-orang yang menjadi korban bencana. Para korban bencana itu tidak hanya memiliki masalah-masalah pada wilayah material ataupun psikologis, tetapi juga masalah pada wilayah spiritual. Dan, persoalan spiritual inilah yang seolah dilupakan di Jepang. Faktanya, di Jepang walaupun bantuan material sangat banyak diberikan oleh pemerintah, misalnya bantuan tempat tinggal dan biaya hidup yang cepat dan mudah dari pemerintah setelah bencana terjadi, namun tetap saja banyak korban bencana yang hidupnya merasa susah, apalagi pasca gempa dan tsunami lima tahun lalu (gempa dan tsunami tahun 2011). Hampir delapan ribu orang yang bunuh diri di wilayah-wilayah terdampak bencana tersebut. Artinya, menangani persoalan yang bersifat material dan medis saja tidaklah cukup. Saya berpikir ini mesti ada persoalan spiritual yang juga harus dibantu penyelesaiannya, dan ini pasti membutuhkan peranan agama. Nah, di dalam konteks inilah kelas religion, science and disaster diadakan. Mengenai persoalan hubungan bencana, sains dan agama, saya sedang melakukan penelitian untuk membandingkan persoalan ini di Jepang dengan wilayah lain, yakni di Indonesia, Turki dan Cina. Sehingga nanti dapat ditemukan formula yang tepat dalam menggunakan agama sebagai mitigasi bencana.

Apakah ada perbedaan antara respon Bencana di Jepang dan Indonesia?

Menurut saya sangat berbeda. Karena di Jepang, pemisahan antara agama dan pemerintahan sangat kuat. Sehingga kadang-kadang bantuan yang bersifat sekular lebih gampang sedangkan yang bersifat agama sangat sulit. Sedangkan di Indonesia peranan agama lebih kuat dalam membantu korban-korban bencana. Di Jepang kesan-kesan terhadap agama sangat negatif sedangkan di sini sangat positif.

Sebenarnya, kondisi agama di Jepang itu sendiri seperti apa, Kimura Sensei?

Kondisi agama di Jepang sangat berbeda dengan di Indonesia. Bisa juga disebut terbalik kondisinya. Di Jepang, kata-kata agama seperti sesuatu yang tabu. Masyarakat Jepang sangat takut dengan kata-kata agama. Saat saya mengatakan kepada orang tua saya bahwa saya akan belajar di religious studies (Studi Agama), mereka melarang. Mungkin mereka takut jika anaknya punya hubungan dengan agama. Bahkan kalau melihat hasil survei, lebih dari tujuh puluh persen masyarakat Jepang mengatakan bahwa dirinya tidak memiliki agama. Hanya dua puluh persen yang mengatakan bahwa dirinya beragama. Namun uniknya, jika melihat hasil survei lainnya, bisa dilihat bahwa kira-kira delapan puluh persen masyarakat Jepang pergi ke kuburan untuk bersembahyang. Kuburan-kuburan tersebut biasanya berada di kuil-kuil Budha dan orang-orang biasanya meminta para biksu untuk mendoakan orang-orang yang telah meninggal. Dan di dalam rumah mereka, hampir lima puluh persen masyarakat Jepang bersembahyang kepada dewa-dewa agama Sinto atau agama Budha. Delapan puluh persen dari mereka pergi berdoa ke kuburan dan lima puluh persen dari mereka setiap hari bersembahyang di rumah namun mereka tidak pernah menganggap hal itu sebagai agama. Orang Jepang berbeda dengan orang atheis. Orang Jepang melakukan beragam praktik keagamaan namun tidak mau mengakui hal itu sebagai praktik agama, alasannya macam-macam, salah satunya yaitu orang Jepang menganggap bahwa kata-kata agama itu adalah impor dari Eropa, dan mereka menganggap bahwa agama itu seperti agama Kristen, ada gereja dan ada organisasi yang kuat dan harus memilih satu agama saja. Hal itu tidak sesuai dengan praktek dan kepercayaan orang Jepang. Sehingga, walaupun mereka pergi ke kuburan dan melakukan sembahyang di rumah namun mereka berpikir hal itu bukanlah agama seperti agama Kristen. Konsep agama dalam pandangan orang Jepang sangatlah sempit.

Lantas, bagaimana respons generasi muda Jepang saat ini terhadap perkembangan agama?

Soal agama-agama baru sebenarnya pasca Perang Dunia Kedua sudah mulai ada, saat masyarakat Jepang berada dalam kondisi yang susah. Waktu itu agama-agama baru mulai tumbuh, dan sekitar tahun 80-an agama-agama baru ini tumbuh di dalam kampus dan menjaring banyak pengikut. Namun sejak tahun 1995, saat terjadi aksi terorisme oleh anggota agama Aum Sinrykyo yang menyebarkan gas sarin di subway, masyarakat Jepang menjadi takut dengan agama baru. Menurut survey, pengikut agama-agama baru itu kini tinggallah orang yang sudah tua-tua dan jumlahnya sudah menurun. Namun, jika melihat hasil survei terbaru, kita bisa lihat bahwa sejak tahun 70-an, jumlah anak-anak muda yang percaya agama terus menurun, namun pasca gempa 2011 agak berubah, mulai agak sedikit naik. Mungkin di generasi muda saat ini sudah mulai tumbuh pandangan positif terhadap agama dibandingkan dengan generasi terdahulu.

Apakah ada perbedaan pandangan orang Jepang terhadap agama sebelum dan setelah tsunami, terutama tsunami besar yang terjadi belakangan ini?

Pasca bencana gempa dan tsunami pada tahun 2011 silam memang ada perubahan cukup berarti dalam cara pandang masyarakat Jepang terhadap agama. Bencana tersebut menelan korban lebih dari lima belas ribu orang meninggal dunia. Di dalam sejarah Jepang, bencana dengan korban sebesar itu sepertinya tidak pernah terjadi sebelumnya. Nah, ini rupanya mengguncang sisi spiritual masyarakat Jepang. Saya mendengar langsung sebuah cerita dari kawan yang seorang dokter dan bertugas mengurus para korban tsunami besar tersebut. Ia ditanya oleh korban selamat dari tsunami tersebut, “Suami saya telah meninggal oleh tsunami, sekarang suami saya kira-kira berada di mana?” Sebagai petugas medis, teman saya waktu itu tidak mampu menjawab. Ia bercerita pada saya dan merasa bahwa untuk menjawab pertanyaan itu bukanlah peranan seorang di bidang medis melainkan agama. Dan selama ini di Jepang, wilayah itu kosong. Nah, saking banyaknya persoalan semacam itu, kini masyarakat Jepang sudah mulai berpikir untuk mencari solusi, salah satunya lewat agama.

Selain itu, media juga sudah mulai berubah. Jika dulu media tidak mau memberitakan perihal agama karena tidak mau campur tangan di dalam persoalan agama, kini setelah gempa dan tsunami besar tersebut, media Jepang mulai banyak memberitakan perihal agama, misalnya memberitakan LSM-LSM agama yang membantu para korban bencana. Mungkin sekarang pikiran masyarakat Jepang sudah mulai berubah. Dahulu masyarakat Jepang berpikir, jika ada bantuan datang dari lembaga-lembaga keagamaan maka itu adalah usaha untuk menyebarkan agama baru pada korban bencana. Namun sekarang mereka mulai memahami bahwa hal itu adalah memang murni untuk bantuan kemanusiaan.

Apakah perubahan pandangan terhadap agama pasca bencana ini juga berpengaruh terhadap minat mahasiswa Jepang terhadap studi agama?

Jika di masa saya, studi agama menargetkan menerima sepuluh orang mahasiswa pada setiap tahun ajaran, tapi paling hanya dua atau tiga orang yang mendaftar. Namun, kini hampir setiap tahun ajaran ada sekitar dua puluh orang yang mendaftar dan sepuluh orang saja yang diterima. Jadi sejak tahun 2000, sudah mulai banyak calon mahasiswa yang mau belajar di jurusan studi agama. Ini tidak hanya terjadi di Universitas Tohoku tetapi juga di universitas-universitas lainnya di Jepang. Jadi, mungkin generasi muda saat ini sudah mulai tertarik mempelajari masalah-masalah agama.

Apa yang diajarkan di jurusan religious studies di Jepang?

Religious studies di Jepang juga mengajarkan hal yang sama seperti di Indonesia, seperti di CRCS. Religious studies mengajarkan teori-teori dari Eropa, semisal sosiologi dan antropologi. Namun memang sejak sebelum terjadi bencana gempa dan tsunami besar pada tahun 2011, studi agama ini lebih banyak berkutat di wilayah teoritis, hanya berputar pada sisi teori-teori saja. Namun pasca 2011, kajian ini mulai menemukan wilayah praktisnya. Sekarang jurusan studi agama mulai banyak menjalin kerja sama dengan LSM-LSM agama atau lembaga agama, tidak seperti dulu yang terkesan menjauhkan diri dari agama. Sekarang studi agama mulai berpikir ke arah kerjasama dengan lembaga agama di dalam menangani persoalan korban bencana.

Apakah kerjasama antara program studi agama di Jepang dengan program studi agama di universitas lain juga termasuk bagian dari itu? Seperti kerja sama antara Tohoku University dan CRCS UGM?

Iya, MoU kerjasama antara Tohoku dan CRCS UGM ini berfungsi seperti payung hukum saja, sedangkan jenis dan bentuk program-program penelitian ataupun pertukaran mahasiswa bisa didesain sedemikian rupa nanti. Pertukaran mahasiswa bisa dilakukan antara mahasiswa CRCS UGM dan Tohoku dan bisa transfer mata kuliah, sedangkan biaya kuliah cukup dengan membayar di home university saja. Secara umum, kerjasama antara Tohoku University dan CRCS UGM ada dua macam, yaitu tentang kerja sama penelitian dan pertukaran mahasiswa. Di bidang penelitian nanti bisa ada kerja sama dalam proyek penelitian, penelitian tentang agama dan bencana salah satunya, dan jika ada penelitian di Jepang nanti ada bantuan fasilitas dari Tohoku University.

Sebagai penutup, bisa sedikit bercerita mengenai pengalaman mengajar di CRCS?

Ini adalah tahun kedua saya mengajar di CRCS. Saya sangat senang mengajar di sini karena setiap tahun mahasiswanya terlihat selalu semangat. Responsnya banyak. Tidak seperti di Jepang. Kalau di Jepang, selesai kelas saya harus menunjuk satu-satu mahasiswa agar mau bertanya. Kalau di sini mahasiswanya aktif bertanya. Jadi diskusinya bisa lebih dalam. Awalnya, sebelum saya mulai mengajar kuliah disaster ini, saya sempat khawatir apakah materi yang akan disampaikan cocok atau tidak, namun ternyata banyak mahasiswa yang tertarik dengan materi yang disampaikan dan kelasnya menjadi hidup. Saya jadi senang sekali.

Arigato Gozaimasu, Kimura Sensei!

Religion, Women, and Literature: Women of Spirit in Christianity, Islam, and Other Religious Traditions

| Lecturer | : | Maria Lichtman (Appalachian State University, USA) |

| Guest Speaker | : | Dewi Chandraningrum (Jurnal Perempuan) |

| Schedule | : | Monday and Wednesday, June 1 – July 30, 2016 |

| Time | : | 09.00 – 12.00 |

This course lifts up from a neglected history those women mystics and visionaries within the Christian and Islamics as well as other world religious traditions whose lives raise questions of what it meant to be a woman of spirit in a thoroughly patriarchal system. It examines briefly the patriarchal context that failed to suppress these women’s spirit and dynamism. The course will look at issues of gender consciousness, dualism vs. integration of soul and body, self-denigration vs. self-affirmation. To what extent do these women transcend their socially constructed identities in reclaiming repressed and persecuted elements of female religious power to become models of spiritual empowerment? To what extent is this possible for women of spirit today? The course will employ as much as possible methods of connected knowing, connecting course readings and discussion to our own experiences and stories. It will seek connections to women within our own religious traditions who embody new possibilities for the place and power of women within religious communities.

Abstract

In this presentation I will explore Robert Bellah’s idea that there were four great axial civilizations which formed the modern world: China, India, Middle Eastern/Abrahamic and Greco-Roman/European. I will suggest that Indonesia occupies a unique role in the modern world because it is not dominated by any one of the 4 axial civilizations but is rather a unique synthesis of all four. Most great nations in the world are dominated by one or two, of these four axial civilizations. My research suggests that most Indonesians hold values and an imagination of social reality which is shaped by all four axial civilizations. In our pluralistic world, Indonesia may hold the key for shaping an Islamic civilization which will bring blessing to the entire world.

Speaker

Bernard Adeney-Risakotta is Professor of Religion and Social Science and International Representative at the Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS-Yogya), in the Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada. He is currently also teaching at Duta Wacana Christian University and Universitas Muhamadiyah Yogyakarta. Bernie completed his B.A. from University of Wisconsin in Asian Studies and Literature. His second degree, a B.D. (Hons.) is from University of London, specializing in Asian Religions and Ethics. Bernie’s Ph.D. is from the Graduate Theological Union (GTU) in cooperation with University of California, Berkeley, in Religion, Society and International Relations. From 1982 until 1991 he taught at the GTU Berkeley. Bernie has been a Fellow at St. Edmunds College, Cambridge and at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS), Amsterdam. From September 2013 to July 2014 he was on sabbatical leave as a Visiting Fellow at the Institute on Religion and World Affairs at Boston University. He has many publications, including: Just War, Political Realism and Faith (1988), Strange Virtues: Ethics in a Multicultural World (1995), Dealing with Diversity: Religion, Globalization, Violence, Gender and Disasters in Indonesia (2013) and Visions of a Good Society in Southeat Asia (in press, 2016). Email: baryogya@gmail.com

Abstract

The spread of religious millenarianism in the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has raised significant questions about religious movement in those countries. The Baha’i religion provides an important case and relevant context as the Baha’i movement has been paralyzed in its country of origin, Iran, since the beginning of the movement in 1844. To avoid persecution and violence, many Baha’i adherents moved to other regions in Southeast Asia. The Baha’i religion is committed to developing educational skills, economic sustainability, gender empowerment, and social movements. Thus, ASEAN encompasses a dynamic and diverse region that aims to provide social, religious, economic, and cultural security for ASEAN citizens. Minority religions such as the Baha’i community, which at the times are victims of conflict and violence, play an important role in achieving those aims. Conversely, religious violence and conflict may be seen as part of the regional deficit in terms of religious freedom and tolerance. In this context, my study tries to examine religious millenarianism and the future evolution of the ASEAN community. The study investigates the co-existence of the Baha’i community with other religious groups such as Muslim, Christian, and Buddhist in their social, political, and cultural negotiations. As the Baha’i engage on some social and political issues in globalization and embrace liberalism and pluralism in the public space, I argue that this study contributes to scholarship in terms of understanding the fate of religious millenarianism in the future of the ASEAN community.

Speaker

Amanah Nurish Ph.D Cand Researcher of Baha’i studies. She is pursuing doctorate at ICRS UGM-Yogyakarta and working as consultant of USAID team-Washington for assessment program, “Fragility and Conflict”. She wrote book chapters, articles, and journals. Her latest publications: Sufism and Baha’ism: The Crossroads of Religious Movement in Southeast Asia (2016, Equinox publisher, London) Perjumpaan Baha’i Dan Syiah Di Asia Tenggara (2016, Maarif Jurnal, Jakarta) Welcoming Baha’i: New Official Religion In Indonesia (2014, The Jakarta Post) Social Injustice and Problem Of Human Rights In Indonesian Baha’is Community (2012, En Arche Journal, Yogyakarta) etc. She received prestigious awards for her academic works such as King Abdullah Bin Abdulazis’s interfaith center-Vienna, SEASREP-Philippine, ENITS-Thailand, Luce & Ford Foundation-USA, ARI-NUS, etc. With her teamwork, she is currently undertaking a broader anthropological research on “ Religious Millenarianism in ASEAN countries” for publication supported by Arizona State University of America.

Abstract

One of the great debates among religious believers is about the relationship between their religion and culture. Is culture an obstacle to religion or is culture its vehicle? This lecture explores the cultural issues within Christianity and the problem and possibilities of the concept of culture to understanding religions. Related themes of history and globalization will be considered.

Speaker

Charles Fahardian, Ph.D is chair and professor of the Department of Religious Studies, Westmont College, Santa Barbara, CA. He has investigated diverse themes such as nation making, globalization, and worship. He teaches courses in the world religions and Christian mission. He studied at Seattle Pacific University (B.A), Yale University (M.Div), and Boston University (Ph.D)

Farihatul Qamariyah | CRCS | Thesis Review

The discourse of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans gender identities) is being contested everywhere lately in global discussion. Identity, gender, and human rights have generally provided the frame work for debate. The issue of LGBT is also critically regarded as a significant case within religion. Scholars such as Kecia Ali and Scott Kugle are attempting to reinterpret and rethink Islam as a religion which is commonly understood as a blessing for all of mankind, in which contextually this religious essence also can accommodate diversity that extends to the acceptance of LGBT Muslims. Another example of this rethinking is the CRCS Student’s, Hary Widyantoro, thesis Rethinking Waria Discourse in Indonesian and Global Islam which examines the collaboration between Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University activists and Waria santri at the Pesantren Waria al-Fatah which is located in Yogyakarta.

This research looks at the collaboration of scholar activists from Syariah and Law Faculty of Nahdlatul Ulama University of Jepara and waria santri (students of Islam who are born male but identify as feminine, terms discussed below), in rethinking and reconstructing the subjectivity of waria in Indonesian Islamic, thinking through the engagement of activities including in the space of social structure and religious lives. Significantly, this study can be a critical instrument in the field of both gender and religious studies, to examine how these scholar-activists are creating new ways of seeing waria from Qur’an and hadith and of teaching Islam to them as the subjects rather than objects of research. Moreover, it shows the process of rethinking which can offer an alternative view and hope for those who are not associated in the binary gender of male and female. The research questions which are raised up are: how do the scholar activists of Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University of Jepara rethink the waria subject position? How did they develop the idea of religious partnership with the Pesantren Waria al-Fatah Yogyakarta? And what kind of waria discourse that the scholar activists suggested to provide a room for waria in social and religious lives?

It is clear that the discourse of LGBT however is not only talked over in the stage of global, but also at a local level such as in Indonesia. To see the case of waria santri in terms of transgender discourse and the activism of NU scholars in the act of collaboration, the author utilizes the theoretical application on Boellstorff’s idea on global and local suggestion and Foucault’s on the term of subjectivity as well as power relation in his genealogical approach. In analysis, using waria as the chosen terminology in this case marks their identity as a local phenomenon rather than transgender women to use a global term. This term became the primary term for this group after it was used by Minister of Religious Affairs Alamsyah in the 1970s. While taking the framework of Boellstorff on subjectivity and power relation, it helps the author in figuring out and understanding completely on how Muslims activists from NU University rethink of waria discourse, and how it is discussed by Muslims activist and the waria in the Pesantren. Additionally, subjectivity becomes the key point where the author can examine the role of waria based on the activists’ perspectives as a subject of their religiosities and of the truth of their beings, rather than only objects of views.

Waria as one of the local terms in Indonesia represents an actor of transgender in LGBT association that often experience such discrimination and become the object of condemnation. For waria, Identity is the main problem in the aspect of gender in Indonesian law. For instance, Indonesian identity cards only provide a male and female gender options, based on the Population Administration Law, and by the Marriage Law (No. 1/1974). By this law, they will have some difficulties to access the public services. Another problem regarding the social recognition, waria is perceived as people with social welfare problems, based on the Regulation of the Ministry of Social Affairs (No. 8/2012) that must be rehabilitated as a kind of solution. Furthermore, in the religious landscape, the content of fiqh (an Islamic jurisprudence) does not have much discussion on waria matters when compared to male and female stuff. Briefly, these are the problems that the scholar activists seek to answer.In the local course of Indonesian context, scholar-activists at Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University of Jepara (UNISNU) educate Islamic religion to transgender students at the Pesantren Waria al-Fatah as the act of acknowledging their existence and their subjectivity to express identity and religiosity within ritual as well as practice.

Addressing this complicated context, the questions of transgender discourse represented by santri waria in this research is not only about the constitutional rights but also attach their religious lives in terms of Islamic teaching and also practice. While what the scholars identify as “humanism” is the basic framework in dealing with this issue, the universal perception of humanism in secular nature is different from the Muslim scholars’ understanding the idea of humanism when it relates to Islamic religion. Referring to this discussion, the NU activists have another view point in looking at waria as a human and Islam as a religion with its blessing for all mankind without exception. Hence, this overview leads them to rethink and reinterpret the particular texts in Islam, and then work with them in collaboration.

Since the term of collaboration becomes the key word in this research, the author gives a general framework on what so – called a collaboration in relation with the context of observation. The background is on the equal relation between scholar-activists and waria santri in the sense that the activists do not force or impose their perspective on waria. For instance, they allow waria santri to pray and to express their identity based on how they feel comfortable with the condition. In regard to the research process, the author conducted interviews and was a participant observer both in the Pesantren Waria al-Fatah in Yogyakarta and in the UNISNU campus, Jepara. He interviewed six Muslims scholar-activists from UNISNU concerning the monthly program they lead in Pesantren Waria especially about how they rethink waria discourse and its relation to religious and social lives, and another important point is on the scholars’ intention to do the collaboration. Furthermore, the author also draws on the history and programs of the pesantren by interviewing Shinta, who became the leader of the pesantren in 2014 following the death of the founder. He also made use of the Religious Practice Partnering Program’s proposal and accountability report and explored the scholars’ institution and communities where they have relation with to get some additional information about their engagement. The additional context is on the scholars’ affiliation, in this case bringing up the background of Nahdlatul Ulama as one of the biggest Muslims socio-religious organization known as Muslim Traditionalist and Indonesian Muslim Movement (PMII) which both of them apply the similar characteristic on ideology which is ahl al-sunnah wa al-jama’ah.

To some extent, the collaboration of scholar activists of Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University and the santri waria at Pesantren Waria Al Falah rethinks the waria subject position in both their social and religious lives. First, they rethink the normative male – female gender binary which is often considered deviant, an assumption which causes the waria to experience rejection and fear in both their social and religious lives. The same thing happens as well in Islamic jurisprudence known as fiqh, where discussion of waria is absent and, consequently, they find it difficult to express their religiosities, including even whether to pray with men in the front or women behind, and which prayer garments to put on in order to pray.

According to Nur Kholis, the leader of the program from NU University and a scholar of fiqhwhose academic interest is the place of waria in Islamic Law, one answer can be found by categorizing waria as Mukhanats, and then considering them as humans equally as others. He argues that waria have existed since the Prophet’s time considered as mukhanats (a term for the men behave like women in Prophet’s time, according to certain hadith) by nature, or by destiny, and not by convenience. Understanding waria as mukhanats based on their gender consciousness can be a gate for waria to find space in Islam and also their social lives. The following significant finding related to this context is on the genealogy of the process of rethinking waria subject position. The author argues that this rethinking is grounded in Islamic Liberation theology and the method of ahl sunnah wa al-jama’ah, as way of thinking within PMII and NU have contributed and influenced how the activists think of waria subject discourse.

The last important landscape is on the perspective seeing waria as the subject of knowledge, sexualities, and religiosities, covered by the term gender consciousness. This term is the result of rethinking and acknowledging waria subjectivity in understanding their subject position in social and religious lives.Pragmatically, this statement provides a tool of framework to recognize waria as equally with others. It can be seen from the real affiliation of several events, which are parts of Religious Practice Partnering Program, such as Isra’ Mi’raj and Fiqh Indonesia Seminar. Furthermore, this kind of recognition emerges within the global and local concept of Islamic liberation theology and aswaja that make them consider waria as minorities which should be protected, rather than discriminated.

Finally, in such reflection, the discourse of LGBT represented by waria santri, the activism of NU scholars, and their interaction in collaboration notify an alternative worldview to discern a global issue from the local context, in this case is Indonesia. The author concludes the result of this research by saying that this kind of discourse is formed through referring Islamic liberation theology, aswaja, and more specifically the term mukhanats, within global Islam. In the process of interaction, these are interpreted and understood within local context of Indonesia presented by waria case in terms of social and religious life through the act of collaboration under the umbrella of Nahdlatul Ulama and PMII, as organizations tied by aswaja both ideology and methodology. In brief, the rethinking of waria space in the context of Indonesian Islam at the intersection of local and global offers a new expectation and gives a recommendation for all people who do not fit gender binaries but they seek religious practice and experience in their lives.

Rethinking Waria Discourse in Indonesian and Global Islam: The Collaboration between Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University Activists and Waria Santri | Author: Hary Widyantoro (CRCS, 2013)

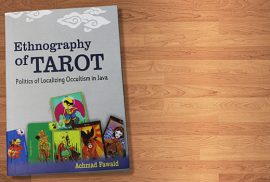

Azis Anwar Fachrudin | CRCS | Book Review

How has Tarot, which was originally foreign to Indonesians, been practiced by Javanese people? Has there been any kind of adaptation of the practice to embrace Javanese local culture? Using etnography as a research method, the book by Achmad Fawaid entitled Ethnography of Tarot: Politics of Localizing Occultism in Java provides historical accounts and analitical study of the localization of the practice in Java.

The main question addressed by the book, originating from Fawaid’s master’s thesis at CRCS, UGM, is how Javanese belief system has made influences on Tarot and its Javanese practitioners. Many of the book’s data are based on interviews with Javanese Tarot practitioners themselves, examined by using the lenses of the theories developed on etnographic studies or anthropology. The book then argues that Javanese Tarot practitioners have “localized” the global “occult” practice and that this localization could be understood in terms of “adaptation”, “acculturation”, indigenization”, or “hybridization”—each of these concepts are elaborated in the book.

The book suggests that in the process of localization the Western Tarot practice has been intertwined with Javanese esoteric occultism. The kebatinan ideas, quite popular among Javanese people, such as tapa, samadi, mutih, wayang performance, and Javenese traditional healing, have been absorbed and carried out in the process of localization—this is the fact that some Javanese Muslims later accuse the practice to be deviant constituting a form of shirk, klenik, perdukunan or a kind of shamanism.

The book suggests that in the process of localization the Western Tarot practice has been intertwined with Javanese esoteric occultism. The kebatinan ideas, quite popular among Javanese people, such as tapa, samadi, mutih, wayang performance, and Javenese traditional healing, have been absorbed and carried out in the process of localization—this is the fact that some Javanese Muslims later accuse the practice to be deviant constituting a form of shirk, klenik, perdukunan or a kind of shamanism.

The research findings the book poses is that (1) Javanese Tarot practitioners have negotiated themselves in the cultic milieu they are living in by “localizing their alias, communities, Tarot reading strategies, Tarot decks, and their personal preference to gather in candi”; and that (2) Tarot practice in Java has closely been connected to some Javanese belief systems, such as rasa and kahanan, and this makes the practitioners practice Javanism, either consciously or unconsciouly, while playing Tarot. Because of these two, Fawaid argues, the localization of Tarot in Java has lead to a “cultural ambivalence” as an implication that the practitioners cannot be free from it as they are practicing global occult practice while maintaining Javanese cultural identity.

In the end, as stated in the epilogue of the book, Fawaid argues that this process of localization as a way of examinig Tarot practices should be a contribution to “occult discourse”. He critizes the common assumption that Tarot reading is strictly divided into three characteristics: psychology, intuition, and spirituality. Fawaid poses one element missing, that is, localization in the forms of abovementioned concepts which should be added in the discourse and which shows a hybridity within Tarot practices between local beliefs and global practices.

Overall, the book lays a foundation for further research on the case; the etnographic accounts of Javanese Tarot have been quite deeply examined in the book. If there is one question to stimulate further research, it can be a more philosophical discussion, that is, why Tarot is considered an occult practice. The book elaborates anthropological concepts (acculturation, indigenization, hybridity, etc.) but for the most part, it seems, it takes the concept of occultism for granted. Occultism, like the concept of religion, which may contain a modern construction of meaning, should be more philosophically discussed and critically examined in the first place. In fact, this has become within the heart of the problem when Javanese Tarot practitioners try to negotiate their identity with religious milieu of Javanese people.

Ethnography of Tarot: Politics of Localizing Occultism in Java | Author: Achmad Fawaid | Publisher: Ganding Pustaka, Yogyakarta | Year Publishing: November 2015 | Pages: 208 pages

A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | News

“Boleh mengambil apa pun dari alam, asal sesuai haknya. Jangan berlebih. Ada hak Allah yang harus dipenuhi di sana, yakni keseimbangan. Namun jika berlebih, maka namanya mencuri, menzalimi hak Allah, mengambil lebih dari haknya.”

Itulah sekelumit nasihat dari Iskandar Waworuntu terhadap para mahasiswa CRCS yang mengadakan kunjungan ke Bumi-Langit, Kamis 17 November 2015. Menempati tanah seluas kurang lebih tiga hektar di wilayah Imogiri, Yogyakarta, Bumi-Langit merupakan tempat tinggal keluarga Iskandar Woworuntu yang sekaligus difungsikan sebagai contoh implementasi dari permaculture. Lokasi ini terletak tak jauh dari Pemakaman Imogiri, tempat dimakamkannya raja-raja Kesultanan Mataram. Bahkan, dari pendopo warung Bumi-Langit, pengunjung dapat melihat secara jelas kompleks pemakaman raja-raja tersebut.

Permaculture sendiri merupakan istilah dari gabungan dua kata, yakni permanent dan agriculture yang kemudian mengalami pergeseran menjadi permanent culture. Permaculture sebagai sebuah sistem yang teratur dan dapat dipelajari serta dipraktikkan mulai dikenalkan oleh Bill Mollison dan David Holmgren pada tahun 1978. Dalam hal ini, Mollison mendefinisikan permaculture sebagai sebuah filosofi tentang kerjasama dengan alam, bukan menaklukannya; tentang pengamatan dan penelusuran dan bukan pemikiran penggarap; tentang memperhatikan terhadap semua fungsi tanaman serta binatang dan bukan pendekatan yang menjadikan sebuah area sebagai sistem produksi tunggal. Artinya, permaculture merupakan sebuah sistem yang didesain sedemikian rupa sehingga dapat memaksimalkan fungsi alam untuk keberlangsungan kehidupan tanpa harus merusak atau menyalahi kodrat alam itu sendiri. Iskandar menyebutkan bahwa permaculture adalah sebuah ilmu untuk mendesain hidup manusia sesuai dengan tugasnya sebagai khalifah—penatalayan atau steward dalam istilah Kristen—di muka bumi, di mana manusia dapat memiliki kemampuan untuk mewujudkan kehidupan sesuai dengan yang dikehendaki oleh Tuhan.

Permaculture sendiri merupakan istilah dari gabungan dua kata, yakni permanent dan agriculture yang kemudian mengalami pergeseran menjadi permanent culture. Permaculture sebagai sebuah sistem yang teratur dan dapat dipelajari serta dipraktikkan mulai dikenalkan oleh Bill Mollison dan David Holmgren pada tahun 1978. Dalam hal ini, Mollison mendefinisikan permaculture sebagai sebuah filosofi tentang kerjasama dengan alam, bukan menaklukannya; tentang pengamatan dan penelusuran dan bukan pemikiran penggarap; tentang memperhatikan terhadap semua fungsi tanaman serta binatang dan bukan pendekatan yang menjadikan sebuah area sebagai sistem produksi tunggal. Artinya, permaculture merupakan sebuah sistem yang didesain sedemikian rupa sehingga dapat memaksimalkan fungsi alam untuk keberlangsungan kehidupan tanpa harus merusak atau menyalahi kodrat alam itu sendiri. Iskandar menyebutkan bahwa permaculture adalah sebuah ilmu untuk mendesain hidup manusia sesuai dengan tugasnya sebagai khalifah—penatalayan atau steward dalam istilah Kristen—di muka bumi, di mana manusia dapat memiliki kemampuan untuk mewujudkan kehidupan sesuai dengan yang dikehendaki oleh Tuhan.

Dalam kunjungan kuliah lapangan ini, rombongan mahasiswa CRCS diajak berkeliling melihat pertanian, peternakan, dan hunian keluarga Iskandar dalam kompleks Bumi-Langit yang terintegrasi dalam sebuah sistem terpadu, di mana seluruh bagian yang ada di Bumi-Langit—semisal peternakan sapi, ayam, dan kelinci, serta ladang dan hunian tempat tinggal manusia—memiliki keterkaitan hubungan yang saling menguntungkan. Sistem pembuangan kotoran manusia dan hewan, misalnya, ditampung di dalam sebuah tempat khusus untuk kemudian diolah menjadi biogas yang digunakan untuk memasak dan keperluan lainnya. Begitu pula, sisa jerami pakan sapi digunakan sebagai pupuk kompos dan lahan pembiakan cacing, di mana cacing-cacing ini dapat digunakan sebagai pakan ternak lainnya serta alat penggembur tanah. Sistem permaculture yang diterapkan di Bumi-Langit memang sangat menekankan akan ketiadaan unsur limbah berlebih yang disebut sebagai fasad oleh Iskandar. Fasad berarti suatu kerusakan yang diakibatkan oleh ulah buruk atau kezaliman manusia, dan salah satu bentuknya adalah limbah.

Menurut Iskandar, limbah dalam kadar kewajarannya bukanlah masalah atau sebuah fasad. Sebab, secara alamiah limbah itu akan terurai dalam waktu yang cukup singkat. Namun, jika limbah itu berada di luar kewajaran akibat adanya campur tangan tindakan buruk manusia—misalnya tindakan eksesif saat menggunakan suatu benda atau sumber daya alam, sehingga limbah yang dihasilkan tidak dapat diurai secara alami atau membutuhkan waktu yang sangat panjang—maka itulah fasad yang harus dihindari. Menurut Iskandar, bumi tempat tinggal manusia, alam dan segala makhluk yang ada ini diciptakan oleh Tuhan dengan ukuran atau kadarnya masing-masing. Ukuran-ukuran itulah yang membuat alam ini berada dalam kondisi yang stabil dan harmoni. Namun, jika ukuran ini diganggu atau diambil tanpa perhitungan yang jelas, kestabilan ini akan terusik dan dapat memicu kerugian yang signifikan bagi kehidupan di bumi ini. Contoh nyata dalam hal ini misalnya bencana longsor atau banjir yang diakibatkan adanya penebangan hutan secara liar dan massif. Secara alami, alam memang memiliki kemampuan untuk menyeimbangkan kembali ukuran-ukuraan yang telah diambil tersebut, namun eksploitasi dan cara-cara eksesif yang dilakukan manusia kerap membuat alam membutuhkan waktu yang lebih lama dalam proses penyeimbangan tersebut, atau bahkan membuat alam sama sekali tidak dapat memperbaikinya sebab kerusakan yang ditimbulkan bersifat permanen.

Menurut Iskandar, limbah dalam kadar kewajarannya bukanlah masalah atau sebuah fasad. Sebab, secara alamiah limbah itu akan terurai dalam waktu yang cukup singkat. Namun, jika limbah itu berada di luar kewajaran akibat adanya campur tangan tindakan buruk manusia—misalnya tindakan eksesif saat menggunakan suatu benda atau sumber daya alam, sehingga limbah yang dihasilkan tidak dapat diurai secara alami atau membutuhkan waktu yang sangat panjang—maka itulah fasad yang harus dihindari. Menurut Iskandar, bumi tempat tinggal manusia, alam dan segala makhluk yang ada ini diciptakan oleh Tuhan dengan ukuran atau kadarnya masing-masing. Ukuran-ukuran itulah yang membuat alam ini berada dalam kondisi yang stabil dan harmoni. Namun, jika ukuran ini diganggu atau diambil tanpa perhitungan yang jelas, kestabilan ini akan terusik dan dapat memicu kerugian yang signifikan bagi kehidupan di bumi ini. Contoh nyata dalam hal ini misalnya bencana longsor atau banjir yang diakibatkan adanya penebangan hutan secara liar dan massif. Secara alami, alam memang memiliki kemampuan untuk menyeimbangkan kembali ukuran-ukuraan yang telah diambil tersebut, namun eksploitasi dan cara-cara eksesif yang dilakukan manusia kerap membuat alam membutuhkan waktu yang lebih lama dalam proses penyeimbangan tersebut, atau bahkan membuat alam sama sekali tidak dapat memperbaikinya sebab kerusakan yang ditimbulkan bersifat permanen.

Menurut Iskandar, hal pertama yang harus dipelajari dan senantiasa dijadikan landasan dalam segala bentuk praktik permaculture adalah etika. Di dalam Islam, etika ini dikenal dengan istilah adab. Di dalam penerapan permaculture ini, Iskandar memang lebih banyak dipengaruhi oleh ajaran Islam yang dianutnya. Menurut iskandar, adab adalah titik awal untuk melakukan apa pun di dunia ini. Tanpa adab, seseorang akan selalu mendapat masalah saat melakukan apa pun. Adab permaculture, menurut Iskandar, ada tiga. Pertama, care for the Earth; kedua, care for humanity; dan ketiga, fair share, baik terhadap manusia maupun ciptaan Tuhan yang lainnya. Bumi berada di urutan pertama sebab ia mewakili alam secara keseluruhan. Dalam hal ini, Iskandar menjelaskan bahwa seseorang tidak akan mungkin memiliki hubungan kemanusiaan yang baik atau sanggup membangun peradaban manusia yang baik jika tidak memiliki etika yang baik terhadap alam. Bahkan, menurutnya, manusia sendiri adalah bagian tak terpisahkan dari alam ini. Manusia yang terdiri dari sistem pencernaan, saraf, napas, atau darah—termasuk pula sistem transenden yang belum dipahami manusia—adalah sebuah internal ekosistem. Sedangkan bumi dan seluruh makhluk lainnya adalah eksternal ekosistem. “Jadi, jika kita tidak memiliki hubungan yang baik dengan internal maupun eksternal ekosistem, tidak mungkin kita memiliki hubungan baik dengan manusia apalagi membangun peradaban,” ucap Iskandar saat ditanya mengapa manusia tidak berada dalam urutan pertama. Hal ini tentu sangat bertolak belakang dengan pemahaman umum yang cenderung bersifat antroposentrisme, di mana manusia menjadi pusat bagi kehidupan di dunia ini.

Iskandar menjelaskan bahwa yang dilakukan oleh permaculture adalah sebuah pendekatan holistik bagi keberlangsungan kehidupan bumi dan peradaban manusia. Dengan adanya pendekatan holistik ini, maka manusia tidak keluar dari kodratnya sebagai khalifah di muka bumi, yakni pihak yang bertanggung jawab untuk mengatur, mengurus dan menjamin keberlangsungan kehidupan di dunia ini dengan harmoni, bukan mengeksploitasi semua kekayaan alam demi kepuasan pribadinya. Karenanya, menurut Iskandar, maksud dari holistik di sini dapat bermakna menyeluruh maupun suci atau agung. Artinya, sistem yang digunakan mestinya tidak keluar dari garis-garis ketentuan Tuhan dan senantiasa bertujuan demi menjalankan perintah-Nya. Dengan begitu, segala perilaku manusia yang hadir di bawah kontrol sistem tersebut dapat dimaknai sebagai bentuk ibadah yang memiliki kontinuitas, sebab nilai-nilai kebaikan yang dibangunnya tidak terhenti pada satu generasi semata. Di dalam bahasa Islam, menurut Iskandar, hal ini disebut dengan amal jariyah, yakni amal perbuatan yang pahalanya senantiasa mengalir terus walau pelaku perbuatan tersebut telah tiada.