A student's reflection on the Talentime movie watched in the CRCS's Religion and Film course.

Southeast Asia

Suhadi | CRCS | Opinion

As i observe, the discipline of religious studies that is growing in Southeast Asian countries nowadays has several characteristics that make it different from how religion has been studied until now. First, it goes beyond theological approaches and stresses religious practice in relation to society, politics and culture. Second, it is part of the response to social and political issues outside the academy, such as inter-religious conflict, the absence of the freedom of religion, gender inequality, social injustice, etc. For these reasons, I am interested to explore the emergence of this discipline in the context of Southeast Asia.

As i observe, the discipline of religious studies that is growing in Southeast Asian countries nowadays has several characteristics that make it different from how religion has been studied until now. First, it goes beyond theological approaches and stresses religious practice in relation to society, politics and culture. Second, it is part of the response to social and political issues outside the academy, such as inter-religious conflict, the absence of the freedom of religion, gender inequality, social injustice, etc. For these reasons, I am interested to explore the emergence of this discipline in the context of Southeast Asia.

I presented these ideas about the emerging discipline of religious studies in the Southeast Asian context at the research seminar entitled “Making Southeast Asia and Beyond” at the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand, in January 2016.

Southeast Asia is home to communities of believers in the world’s major religions and traditions, in addition to various indigenous religions and other smaller world religions. Major groups by percentage of the Southeast Asian population are Muslims (36.77%), Buddhist (26.78%), Christians (22.06 %), and ethno-religionists (4.61 %), according to www.thearda.com. Others include Hindus, Confucians, and members of other faiths.

The significance of religions in Southeast Asia is not only in their strong presence in the daily life of society, but also in the profound role they play in various aspects of political, economic, and social life of the Southeast Asian peoples. In previous decades, it was predicted that due to the strong modernization of Southeast Asia –like in other parts of the world– religion would disappear from public life. However, the turn of the twenty-first century has seen a resurgence in religious activity. Despite predictions of its decline, religion has revived (and, some scholars add, become radicalized) around the globe, including in Southeast Asia. It has not died out in our modern world, as secularization theory anticipated, but, on the contrary, it is blossoming. Some scholars even call the 21st century “God’s century” (Toft et al. 2011).

Religious issues occupy a strategic, challenging position in the political, economic, and social life of Southeast Asian countries. Intra- and interreligious tension and conflict arise frequently in the region and, to varying degrees, persecution based on religious identity has been reported in some ASEAN member states (Human Rights Resources Center at UI Jakarta 2015). The conflict between Buddhist majority groups in Myanmar supported by the government and the Muslim minority Rohingya has led to the displacement of Rohingya refugees to camps inside Myanmar and to other other ASEAN countries (Suaedy& Hafiz 2015). These problems show the complexity of identity issue, including religious identity issue, in Southeast Asian countries and beyond. Acts of religious inspired terrorism have been making the problems more complex.

Meanwhile, as shown by the consensus of the ASEAN Economic Community which was launched this January 2016, the concerns of ASEAN leaders have focussed mostly (to not say merely) on economic interests. We do have the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration which pays attention to civil, political, and cultural rights and the people’sright to peace, but it pays little attention to religious rights. The ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights advocates for the rights of migrants, women, children, and disabled people, but had done little in regards to religious rights. It seems the actors try to avoid religious issues.

Thus, it is necessary to ask such questions as where is the place for talking about inter/ intra religious issues in the public life since religion isin fact part of public discourse? Who will initiate opening that discussion? What is the role of public (non-theological, non-religious vocational) universities in this region on these issues?

In this article, I will try to answer the last question based on the assumption that the answer must indirectly respond to the preceding questions. I look at how public universities in Southeast Asian countries are initiating the academic study of religions during the last two decades by opening centers or departments with the title religious studies or similar names.

Of course, religions have long been studied widely in universities in the region, usually from the perspective of theology or as the (social) science of religion within such disciplines as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and so on. It is important to differentiate among the three positions: theology, (social) science of religion, and religious studies, which tends to be interdisciplinary in its approach. My main concern here is religious studies.

Let us come to see the institutional development of religious studies in several universities in Southeast Asia. I focus on three institutions, among others as examples. First,the College of Religious Studies in Mahidol University in Thailand was established in 1999 and dedicated to “the study and research in the field of religious studies [that]fosters mutual understanding, cooperation, and respect among people of different religious traditions”. A strong International Center for Buddhism and Islamis part of that college. (http://www.crs.mahidol.ac.th/).

Second, at GadjahMada University Indonesia, the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS) interdisciplinary master program focusing on religious studies was established in 2000. It has three main areas of study: inter-religious relations; religion, culture and nature; and religion and public life (crcs.ugm.ac.id).

Third, it is a little surprising that in 2014 Nanyang Technological University in Singapore also opened a master program entitled “Studies in Inter-Religious Relations in Plural Societies” within its Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). It is mentioned in its profile that it “aims to study various models of how religious communities develop their teachings to meet the contemporary challenges of living in plural societies. It will also deepen the study of inter-religious relations, formulate models for the positive role of religions in peace-building and produce knowledge to strengthen social ties between communities” (www.rsis.edu.sg/research/srp/).

These aforementioned institutions offer academic degrees in religious studies (BA, MA, and/ or PhD). The main character of religious studies as each defines it is strengthening inter-religious perspectives. In consequence, the religious studies approach draws directly or indirectly on comparative studies within religious diversity either as social context or as a primary concern of study. In this point we can see one major difference in perspective and positionality between religious studies and theology.

Thus, on one hand, it is in line with the duty of the public university to understand about diverse religions rather than to preachon behalf of one religion. In addition those institutions are engaged in peace movements and other activities related to diversity management in their respective societies. In this point, the religious studies perspective, by seeking to be impartial but not neutral, is different from that of the science of religion that usually –not always—strives to be neutral.

In conclusion, considering the awkwardness of public universities and other public bodies and authorities within ASEAN in ‘addressing’ religion, it is clear that it is time to look at religious studies as an alternative approach. Religious studies recognizes the significance of religion in Southeast Asian political, economic, and social life. Maybe it is not an over statement to say that the centers and departments of religious studies in Southeast Asian public universities –in cooperation with other disciplines– will be new players in relation to the management of religious diversity in the public life of Southeast Asia.

The writer is a lecturer at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS),

Graduate School, GadjahMada University, Indonesia.

He can be reached at: suhadi_cholil@ugm.ac.id

Abstract

The spread of religious millenarianism in the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has raised significant questions about religious movement in those countries. The Baha’i religion provides an important case and relevant context as the Baha’i movement has been paralyzed in its country of origin, Iran, since the beginning of the movement in 1844. To avoid persecution and violence, many Baha’i adherents moved to other regions in Southeast Asia. The Baha’i religion is committed to developing educational skills, economic sustainability, gender empowerment, and social movements. Thus, ASEAN encompasses a dynamic and diverse region that aims to provide social, religious, economic, and cultural security for ASEAN citizens. Minority religions such as the Baha’i community, which at the times are victims of conflict and violence, play an important role in achieving those aims. Conversely, religious violence and conflict may be seen as part of the regional deficit in terms of religious freedom and tolerance. In this context, my study tries to examine religious millenarianism and the future evolution of the ASEAN community. The study investigates the co-existence of the Baha’i community with other religious groups such as Muslim, Christian, and Buddhist in their social, political, and cultural negotiations. As the Baha’i engage on some social and political issues in globalization and embrace liberalism and pluralism in the public space, I argue that this study contributes to scholarship in terms of understanding the fate of religious millenarianism in the future of the ASEAN community.

Speaker

Amanah Nurish Ph.D Cand Researcher of Baha’i studies. She is pursuing doctorate at ICRS UGM-Yogyakarta and working as consultant of USAID team-Washington for assessment program, “Fragility and Conflict”. She wrote book chapters, articles, and journals. Her latest publications: Sufism and Baha’ism: The Crossroads of Religious Movement in Southeast Asia (2016, Equinox publisher, London) Perjumpaan Baha’i Dan Syiah Di Asia Tenggara (2016, Maarif Jurnal, Jakarta) Welcoming Baha’i: New Official Religion In Indonesia (2014, The Jakarta Post) Social Injustice and Problem Of Human Rights In Indonesian Baha’is Community (2012, En Arche Journal, Yogyakarta) etc. She received prestigious awards for her academic works such as King Abdullah Bin Abdulazis’s interfaith center-Vienna, SEASREP-Philippine, ENITS-Thailand, Luce & Ford Foundation-USA, ARI-NUS, etc. With her teamwork, she is currently undertaking a broader anthropological research on “ Religious Millenarianism in ASEAN countries” for publication supported by Arizona State University of America.

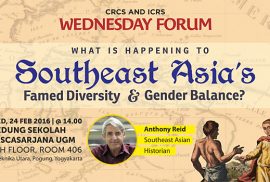

Abstract

Among Southeast Asia’s many distinctive features, some would say stereotypes, there are two which I have helped to build. The first is its great diversity of language, religion, mode of production and political organization, where ‘empires failed to unify’ and stateless hunter-gatherers may still be found. The second is the economic autonomy of women, who had their own secure share in production (planting, harvesting, textiles, pottery, marketing) and therefore an almost uniquely strong position in sexual politics. As an historian, I was excited to demonstrate both features in the era before modernity entranced the region around 1900. Today’s students are entitled to ask, ‘Then what happened?’ Does modernity require nationalist homogeneity and patriarchy? Or was the region seduced by a peculiar ‘Victorian’ model of colonial modernity that could never really succeed in such a context?

Speaker

Anthony Reid is a Southeast Asian historian, once again based at the Australian National University after serving as founding Director of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at UCLA (1999-2002) and of the Asia Research Institute at NUS, Singapore (2002-7). Since 2004 he has been increasingly interested in the impact of natural disasters on Southeast Asian history. His books include The Contest for North Sumatra: Aceh, the Netherlands and Britain, 1858-98 (1969); The Indonesian National Revolution (1974); The Blood of the People: Revolution and the End of Traditional Rule in Northern Sumatra (1979); Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, c.1450-1680 (2 vols. 1988-93); An Indonesian Frontier: Acehnese and other histories of Sumatra (2004); Imperial Alchemy: Nationalism and political identity in Southeast Asia (2010); To Nation by Revolution: Indonesia in the 20th Century (2011); and A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads (2015).

Farihatul Qamariyah | CRCS | News

New work in exploring new directions in re-contextualizing and re-conceptualizing Southeast Asia and Southeast Asian Studies was the main feature of the international conference hosted by Southeast Asian Studies Program and International Studies (ASEAN – China) International Program, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand. This program was conducted in the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University Tha Phrachan center in Bangkok on 15 – 16 January 2016. It was the second event held by the center of Southeast Asian Studies, Thammasat University in collaboration with University of Gadjah Mada Research Center. The first was held on 2 – 3 May 2014 at Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

New work in exploring new directions in re-contextualizing and re-conceptualizing Southeast Asia and Southeast Asian Studies was the main feature of the international conference hosted by Southeast Asian Studies Program and International Studies (ASEAN – China) International Program, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand. This program was conducted in the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University Tha Phrachan center in Bangkok on 15 – 16 January 2016. It was the second event held by the center of Southeast Asian Studies, Thammasat University in collaboration with University of Gadjah Mada Research Center. The first was held on 2 – 3 May 2014 at Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

As shown in its title “Making Southeast Asia and Beyond,” this conference had three important objectives. First, it was a space to encourage the exchange of views, experiences, and findings among senior scholars, young researchers and students. The second objective was to offer a platform for students to present their research and findings. The last, this event becomes the medium to promote academic and research collaboration between universities in ASEAN Community. The conference welcomed a variety of papers dealing with historical, cultural, political, social, religious, or multidisciplinary researches as the stage to share and engage issues concerning Southeast Asia.

This conference was attended by many scholars, graduate students, and researchers coming from several universities in Thailand and Indonesia. During two days, there were three seminar sessions and five panel discussions. The topics of the seminars were “New players in Southeast Asia,” “Southeast Asia and East Asia: Interconnections,” and “Indonesia and Muslim Studies: a New Perspective.” The panel discussions were focused on “Media and Business in Southeast Asia,” “Religion and Identity,” “Tourism and Management,” “Cultural Politics in Asia,” and “Memory and Modernity.”

This conference was attended by many scholars, graduate students, and researchers coming from several universities in Thailand and Indonesia. During two days, there were three seminar sessions and five panel discussions. The topics of the seminars were “New players in Southeast Asia,” “Southeast Asia and East Asia: Interconnections,” and “Indonesia and Muslim Studies: a New Perspective.” The panel discussions were focused on “Media and Business in Southeast Asia,” “Religion and Identity,” “Tourism and Management,” “Cultural Politics in Asia,” and “Memory and Modernity.”

The heart of motivation for this program could be summed up through some words delivered by the keynote speaker, Emeritus Professor Charnvit Kasetsiri from Thammasat University. In the opening session of his speech topic “From Southeast Asian Studies to ASEAN: Back to the Future?” he said that the opportunities are good for Southeast Asia and for ASEAN, but the region also needs integration –the possibility of a dream of one vision, one identity, and one community. Consequently, our efforts to reach this future, should be in line with the blueprints for political security, and all economic, and socio – cultural aspects in the ASEAN charter.

The Center of Religion and Cross – cultural Studies (CRCS), University of Gadjah Mada, was also invited to participate in this conference. Suhadi, as one of the lecturers, was a speaker in the first session of the seminar entitled “New Players in Southeast Asia” from the perspective of religious studies. Two students, Farihatul Qamariyah and Abdul Mujib from the batch 2014, presented their papers in the panel discussion on “Religion and Identity.” (Editor: Greg Vanderbilt)