Esai foto dari ibadah dan perayaan Natal di GKJ, GPIB, GKI, dan HKBP Yogyakarta, 24 Desember 2018.

Yogyakarta

CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum, Sept 6, 2017. Speaker: Dr. Mohammad Iqbal Ahnaf.

A review of the book "Crisis of Keistimewaan: Violence Toward Minorities in Yogyakarta" recently published by CRCS (2017).

Review buku Krisis Keistimewaan: Kekerasan terhadap Minoritas di Yogyakarta (CRCS 2017)

“Gereja-gereja memahami perdamaian secara sempit, sekadar sebagai negative peace. Perdamaian dianggap tercapai apabila tidak ada konflik.”

Anang G Alfian | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

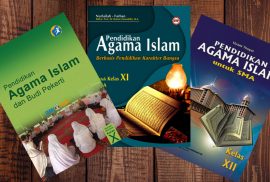

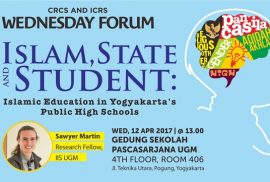

At the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on April 12th, 2107, Sawyer Martin French, a research fellow at the Institute for International Studies at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Universitas Gadjah Mada, gave presentation on the government-mandated curricula of Islamic education in public high schools. He took several public high schools (Sekolah Menengah Atas, SMA) in the province of Yogyakarta, with the method of classroom observation, interviews with teachers, and student focus group discussions in a few schools. More importantly, he also presented his research on Islamic textbooks used in those high schools which he observed have undergone content changes.

In his presentation, French showed that each political period has a difference in the emphasis of the contents of the Islamic textbooks used in SMA. There are three political periods where curricula for Islamic education in SMA have evolved, from the 1994 curriculum, which was formed under the Suharto New Order’s regime; then replaced by the 2006 curriculum under the post-reformation period; and the latest, 2013 curriculum. French shows the content of the Islamic curricula has undergone several changes, three main of which are that related to tolerance, democracy and gender issues.

Regarding democracy, French mentioned an example of 1994 Islamic textbook mentioning the importance of “mushawarah” (lit. consultation to each other) as an Islamic teaching in managing Indonesian politics and governmental administrations. The 2003 textbook mentioned the importance of being a good citizen, meaning a democratic citizen, by further interpreting the meaning of mushawarah. This shows the change due to discourse on democracy generated by reformation. In the 2013 textbook, there is a reference to put more details of how Indonesia democracy should take the ideal shape, and that is to take the example set by the Medinan charter during the time of the Prophet.

Relating to tolerance, the textbooks show changes in the way Muslim should deal with other religions or Islamic sects. In the 1994 textbook, Pancasila was referred to as be the basis of harmony among religious communities while in the 2006 textbook, tolerance can be built along social matters but not along religious lines. The 2013 textbook mentioned that tolerance is a tool to unite the nation, but there are a few sentences which suggest intolerance against some Islamic sects, such as that some Sufi orders practice bid’ah or heretical rituals and that Shiites and Ahmadis are deviant and beyond the limit of tolerance.

As on gender issues, the dominant content of the 1994 textbook upholds the obligation of men as the leader of the family and women as the one who must be obedient to her husband. This was set as an example of a good family. In the 2013 textbook, the focus was more to a companionate marriage and mutual relationship. The notions of housewife and superiority of men which were mentioned in the previous textbooks are now gone and replaced by sentences suggesting a more equal relationship between the husband and the wife, though there is still an emphasis that, despite the same level, “their roles are different.”

*Anang G Alfian is CRCS student of the 2016 batch

Abstract

One of the most significant ways the Indonesian state plays an active role in the country’s religious life is through education: Muslim students at all levels are required to take Islamic education classes, for which the government writes curricula and employs teachers. Therefore, the state—from the center at the Ministry of Religious Affairs to the periphery at individual teacher at public schools—has considerable power to shape religious perspectives of each new generation. His ongoing research is an ethnographic study of Islamic education in public high schools (Sekolah Menengah Atas Negeri) in the province of Yogyakarta, carried out through classroom observation, teacher interviews, and student focus groups. He will present the characteristics and effects of Islamic education in three fields: (a) perspective of religious diversity within Islam; (b) the valorization of the democratic nation-state as Islamic; and (c) the gender ideologies promoted as normatively Islamic. It is also noted how these phenomena vary in and among schools, noting the influence of socio-economic class, education, gender and religious background.

Speaker

Sawyer Martin French is research fellow at the Institute for International Studies at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Universitas Gadjah Mada. He is currently conducting a yearlong research project on Islamic education in public high schools in Yogyakarta with the support of a grant in socio-cultural anthropology from the National Science Foundation.

Look at the full poster of the event here.

Abstract:

Urban people are always exposed to soundscape, to sounds and noises in their everyday life. With the aid of technology, the soundscape of Yogyakarta has dramatically changed in the last 30-40 years. The sounds which once gave certain characteristics to the city have changed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For most people it does not bother them if they do not pay attention to them. However, people accept certain sounds as acceptable sounds while some other may reject them as disturbing noises. The result of such perceptions create spsychologically different responses, either positively or negatively. Therefore, exploring how people in the City of Tolerance responding to the religious soundscape of the place where they live is an effort to see an interfaith relationship from a different perspective, the auditory angle.

Speaker:

Jeanny Dhewayani, Ph.D. is the Associate Director of Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS) Yogyakarta.She got her Master degree from University of New Mexico and Ph.D. from Australian National University, both in Anthropology. Now, She is also a professor of anthropology at Duta Wacana Christian University.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Quoting the great French novelist Victor Hugo’s remark that “Life is a compilation of stories written by God” Inandiak highlighted how meaning is found in stories which come before larger systems like religion. In her book and her talk, she told stories from her experiences with the victims of natural disasters in two communities, one, Kinahrejo, in the North and one, Bebekan,in the South. Inandiak explained that the process of recovery after a natural disaster is a process with and within the nature. It is about the reconciliation between human communities and nature. In natural disasters people mostly lose their belongings such houses, money, clothes and domesticated animals, but, she said, the most important thing is not to lose their identity. Houses can be rebuilt, but once people lose identity they don’t know how to rebuild anything else. Inandiak spoke about the disaster as a conversation between the North and the South. This is also a kind of stories that helps people deal with their situation, by accepting that disaster are part of natural cycles.

Inandiak also spoke about rituals. First there were the rituals enacted by Mbah Maridjan and Ibu Pojo, the shamaness who was his unacknowledged partner, to connect human communities and nature. The offering ritual they made to Merapi included three important layers that describes their own identities: ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam especially Sufism. Despite all the issues that Mbah Marijan and Ibu Pojo faced before they died in the 2010 eruption, they insisted what they were doing is an act of communicating with the nature that was their home. Second, in order to overcome the difficulties after a disaster, stories and ritual mean a lot for reestablishing the victims’ identity. By doing rituals like dancing or singing, they connect to the wishes that become true. The wishes that they made bring such a different in their perspectives in continuing life. Through ritual people want to get connected with nature and Inandiak told how she helped these villages rebuild their identities.

In the question and answer session, we were moved by many fascinating question about the relation of nature and person. One of them is how the three layers in Javanese ritual—reverence for ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam, particularly Sufism—deal with the interference of world religion. Inandiak responded that there must be many changes brings by the world religion, especially in Kinahrejo, where Mbah Maridjan faced pressure from fundamentalists. The way villagers perceive myth changes from time to time. Their Muslim-Javanese identity is something they need to maintain in negotiation. In answering the issues about participants in the rituals wearing hijab, Inandiak argued that these layers should be clearer. They are not rooted in one story. But to maintain the customs is also important.

Inandiak closed her presentation with a remarkable message that disasters come from the interaction of people and nature but no one should feel guilty or think that any disaster is the result of sin or human mistakes. The most important things are not to give up and to work to rebuild identity.

Farihatul Qamariyah | CRCS | Thesis Review

The discourse of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans gender identities) is being contested everywhere lately in global discussion. Identity, gender, and human rights have generally provided the frame work for debate. The issue of LGBT is also critically regarded as a significant case within religion. Scholars such as Kecia Ali and Scott Kugle are attempting to reinterpret and rethink Islam as a religion which is commonly understood as a blessing for all of mankind, in which contextually this religious essence also can accommodate diversity that extends to the acceptance of LGBT Muslims. Another example of this rethinking is the CRCS Student’s, Hary Widyantoro, thesis Rethinking Waria Discourse in Indonesian and Global Islam which examines the collaboration between Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University activists and Waria santri at the Pesantren Waria al-Fatah which is located in Yogyakarta.

This research looks at the collaboration of scholar activists from Syariah and Law Faculty of Nahdlatul Ulama University of Jepara and waria santri (students of Islam who are born male but identify as feminine, terms discussed below), in rethinking and reconstructing the subjectivity of waria in Indonesian Islamic, thinking through the engagement of activities including in the space of social structure and religious lives. Significantly, this study can be a critical instrument in the field of both gender and religious studies, to examine how these scholar-activists are creating new ways of seeing waria from Qur’an and hadith and of teaching Islam to them as the subjects rather than objects of research. Moreover, it shows the process of rethinking which can offer an alternative view and hope for those who are not associated in the binary gender of male and female. The research questions which are raised up are: how do the scholar activists of Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University of Jepara rethink the waria subject position? How did they develop the idea of religious partnership with the Pesantren Waria al-Fatah Yogyakarta? And what kind of waria discourse that the scholar activists suggested to provide a room for waria in social and religious lives?

It is clear that the discourse of LGBT however is not only talked over in the stage of global, but also at a local level such as in Indonesia. To see the case of waria santri in terms of transgender discourse and the activism of NU scholars in the act of collaboration, the author utilizes the theoretical application on Boellstorff’s idea on global and local suggestion and Foucault’s on the term of subjectivity as well as power relation in his genealogical approach. In analysis, using waria as the chosen terminology in this case marks their identity as a local phenomenon rather than transgender women to use a global term. This term became the primary term for this group after it was used by Minister of Religious Affairs Alamsyah in the 1970s. While taking the framework of Boellstorff on subjectivity and power relation, it helps the author in figuring out and understanding completely on how Muslims activists from NU University rethink of waria discourse, and how it is discussed by Muslims activist and the waria in the Pesantren. Additionally, subjectivity becomes the key point where the author can examine the role of waria based on the activists’ perspectives as a subject of their religiosities and of the truth of their beings, rather than only objects of views.

Waria as one of the local terms in Indonesia represents an actor of transgender in LGBT association that often experience such discrimination and become the object of condemnation. For waria, Identity is the main problem in the aspect of gender in Indonesian law. For instance, Indonesian identity cards only provide a male and female gender options, based on the Population Administration Law, and by the Marriage Law (No. 1/1974). By this law, they will have some difficulties to access the public services. Another problem regarding the social recognition, waria is perceived as people with social welfare problems, based on the Regulation of the Ministry of Social Affairs (No. 8/2012) that must be rehabilitated as a kind of solution. Furthermore, in the religious landscape, the content of fiqh (an Islamic jurisprudence) does not have much discussion on waria matters when compared to male and female stuff. Briefly, these are the problems that the scholar activists seek to answer.In the local course of Indonesian context, scholar-activists at Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University of Jepara (UNISNU) educate Islamic religion to transgender students at the Pesantren Waria al-Fatah as the act of acknowledging their existence and their subjectivity to express identity and religiosity within ritual as well as practice.

Addressing this complicated context, the questions of transgender discourse represented by santri waria in this research is not only about the constitutional rights but also attach their religious lives in terms of Islamic teaching and also practice. While what the scholars identify as “humanism” is the basic framework in dealing with this issue, the universal perception of humanism in secular nature is different from the Muslim scholars’ understanding the idea of humanism when it relates to Islamic religion. Referring to this discussion, the NU activists have another view point in looking at waria as a human and Islam as a religion with its blessing for all mankind without exception. Hence, this overview leads them to rethink and reinterpret the particular texts in Islam, and then work with them in collaboration.

Since the term of collaboration becomes the key word in this research, the author gives a general framework on what so – called a collaboration in relation with the context of observation. The background is on the equal relation between scholar-activists and waria santri in the sense that the activists do not force or impose their perspective on waria. For instance, they allow waria santri to pray and to express their identity based on how they feel comfortable with the condition. In regard to the research process, the author conducted interviews and was a participant observer both in the Pesantren Waria al-Fatah in Yogyakarta and in the UNISNU campus, Jepara. He interviewed six Muslims scholar-activists from UNISNU concerning the monthly program they lead in Pesantren Waria especially about how they rethink waria discourse and its relation to religious and social lives, and another important point is on the scholars’ intention to do the collaboration. Furthermore, the author also draws on the history and programs of the pesantren by interviewing Shinta, who became the leader of the pesantren in 2014 following the death of the founder. He also made use of the Religious Practice Partnering Program’s proposal and accountability report and explored the scholars’ institution and communities where they have relation with to get some additional information about their engagement. The additional context is on the scholars’ affiliation, in this case bringing up the background of Nahdlatul Ulama as one of the biggest Muslims socio-religious organization known as Muslim Traditionalist and Indonesian Muslim Movement (PMII) which both of them apply the similar characteristic on ideology which is ahl al-sunnah wa al-jama’ah.

To some extent, the collaboration of scholar activists of Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University and the santri waria at Pesantren Waria Al Falah rethinks the waria subject position in both their social and religious lives. First, they rethink the normative male – female gender binary which is often considered deviant, an assumption which causes the waria to experience rejection and fear in both their social and religious lives. The same thing happens as well in Islamic jurisprudence known as fiqh, where discussion of waria is absent and, consequently, they find it difficult to express their religiosities, including even whether to pray with men in the front or women behind, and which prayer garments to put on in order to pray.

According to Nur Kholis, the leader of the program from NU University and a scholar of fiqhwhose academic interest is the place of waria in Islamic Law, one answer can be found by categorizing waria as Mukhanats, and then considering them as humans equally as others. He argues that waria have existed since the Prophet’s time considered as mukhanats (a term for the men behave like women in Prophet’s time, according to certain hadith) by nature, or by destiny, and not by convenience. Understanding waria as mukhanats based on their gender consciousness can be a gate for waria to find space in Islam and also their social lives. The following significant finding related to this context is on the genealogy of the process of rethinking waria subject position. The author argues that this rethinking is grounded in Islamic Liberation theology and the method of ahl sunnah wa al-jama’ah, as way of thinking within PMII and NU have contributed and influenced how the activists think of waria subject discourse.

The last important landscape is on the perspective seeing waria as the subject of knowledge, sexualities, and religiosities, covered by the term gender consciousness. This term is the result of rethinking and acknowledging waria subjectivity in understanding their subject position in social and religious lives.Pragmatically, this statement provides a tool of framework to recognize waria as equally with others. It can be seen from the real affiliation of several events, which are parts of Religious Practice Partnering Program, such as Isra’ Mi’raj and Fiqh Indonesia Seminar. Furthermore, this kind of recognition emerges within the global and local concept of Islamic liberation theology and aswaja that make them consider waria as minorities which should be protected, rather than discriminated.

Finally, in such reflection, the discourse of LGBT represented by waria santri, the activism of NU scholars, and their interaction in collaboration notify an alternative worldview to discern a global issue from the local context, in this case is Indonesia. The author concludes the result of this research by saying that this kind of discourse is formed through referring Islamic liberation theology, aswaja, and more specifically the term mukhanats, within global Islam. In the process of interaction, these are interpreted and understood within local context of Indonesia presented by waria case in terms of social and religious life through the act of collaboration under the umbrella of Nahdlatul Ulama and PMII, as organizations tied by aswaja both ideology and methodology. In brief, the rethinking of waria space in the context of Indonesian Islam at the intersection of local and global offers a new expectation and gives a recommendation for all people who do not fit gender binaries but they seek religious practice and experience in their lives.

Rethinking Waria Discourse in Indonesian and Global Islam: The Collaboration between Nahdlatul Ulama Islamic University Activists and Waria Santri | Author: Hary Widyantoro (CRCS, 2013)

A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | News

Agar gelar “City of Tolerance” Yogyakarta tak sekadar slogan, warga Yogyakarta harus terlibat aktif dan berani mendorong pemerintah untuk melakukan langkah-langkah strategis. Itulah kesimpulan diskusi selama kurang lebih tiga jam pada “Refleksi Dinamika dan Tantangan Kemajemukan di Yogyakarta 2015-2016”, Senin, 11 Januari 2016. Bertempat di kantor Kementerian Agama Kota Yogyakarta, diskusi hasil kerjasama antara Institut DIAN/Interfidei, Forum Kerukunan Umat Beragama (FKUB) DIY dan Aliansi Jurnalis Independen (AJI) DIY ini menghadirkan tiga narasumber dari latar belakang berbeda, antara lain Prof. Noorhaidi Hasan MA., MPhil., PhD, dari akademisi; Agung Supriyono, SH., kepala Kepala Badan Kesbangpol DIY; dan Tomy Apriando dari Aliansi Jurnalis Independen (AJI) Yogyakarta.

Dalam kesempatan tersebut, Noorhaidi membeberkan penelitian Wahid Institute yang menyematkan Yogyakarta sebagai kota intoleran peringkat kedua di Indonesia. Menurut Direktur Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta ini, sepanjang tahun 2014 dan 2015 terjadi lebih dari dua puluh satu kasus kekerasan agama di Yogyakarta. Di antaranya, penyerangan terhadap kantor LKiS saat menghelat diskusi bersama Irshad Manji, penyegelan kantor Ahmadiyah Yogyakarta, kampanye massif anti-Syiah, pembubaran aktivitas Yayasan Rausyan Fikr, perusakan dan penyegelan sejumlah gereja, penolakan perayaan Paskah bersama di Gunung Kidul, serta pembubaran kemah pelajar Kristen. Kasus-kasus semacam ini menjadi ironi bagi Yogyakarta yang digadang-gadang sebagai kota tempat bernaung beragam suku dan agama yang ada di Indonesia.

Dalam kesempatan tersebut, Noorhaidi membeberkan penelitian Wahid Institute yang menyematkan Yogyakarta sebagai kota intoleran peringkat kedua di Indonesia. Menurut Direktur Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta ini, sepanjang tahun 2014 dan 2015 terjadi lebih dari dua puluh satu kasus kekerasan agama di Yogyakarta. Di antaranya, penyerangan terhadap kantor LKiS saat menghelat diskusi bersama Irshad Manji, penyegelan kantor Ahmadiyah Yogyakarta, kampanye massif anti-Syiah, pembubaran aktivitas Yayasan Rausyan Fikr, perusakan dan penyegelan sejumlah gereja, penolakan perayaan Paskah bersama di Gunung Kidul, serta pembubaran kemah pelajar Kristen. Kasus-kasus semacam ini menjadi ironi bagi Yogyakarta yang digadang-gadang sebagai kota tempat bernaung beragam suku dan agama yang ada di Indonesia.

Yang menarik, Noorhaidi juga mencatat Yogyakarta sebagai tempat lahir dan besar organisasi keagamaan dan gerakan yang sering dianggap sebagai pemicu konfrontasi dan intoleransi . Semisal FUI yang sejak tahun 2000 getol memprotes pendirian gereja di Yogyakarta, seperti Gereja GIDI di Kalasan serta Kapel St. Antonius di Pondokrejo. Selain itu, organisasi ini juga lantang menentang eksistensi Ahmadiyah dan Syiah. Yogyakarta juga menjadi saksi lahirnya Laskar Jihad yang turut serta dalam pengiriman laskar Islam ke Poso dan Ambon. Di luar itu, masih ada organisasi lainnya yang juga lahir dan berkiprah di Yogyakarta, semisal MMI yang bertekad menegakkan syariah atau HTI yang senantiasa menyerukan khilafah. Pada kurun waktu yang sama, sekelompok anak-anak muda dari Gerakan Anti Maksiat (GAM), Front Jihad Islam (FJI), Laskar Mujahidin MMI, GPK, KOKAM, dan Al-Misbah juga aktif turun ke jalan menentang Syiah.

Menurut Noorhaidi, ada tiga alasan banyak organisasi keagamaan itu memilih Yogyakarta sebagai arena pergerakannya. Pertama, Yogyakarta adalah kota tujuan para pelajar dan mahasiswa dari berbagai wilayah di Indonesia untuk menuntut ilmu. Dengan begitu, Yogyakarta menjadi lokasi strategis untuk membangun tulang punggung organisasi dan titik sebar gerakan ke berbagai wilayah. Kedua, iklim budaya dan kemasyarakatan di Yogyakarta yang cukup permisif terhadap kelompok atau ajaran-ajaran baru yang muncul. Selain itu, struktur kesempatan politik yang diperankan oleh beberapa orang atau beberapa pihak membutuhkan kehadiran organisasi-organisasi tersebut demi menyokong kekuasaannya, dan begitu pula sebaliknya.

Sementara itu, Agus Supriyono menyebutkan Yogyakarta sebagai barometer dan miniature Indonesia dengan segala keragamannya. Karenanya, menurut Agus, wajar jika ada beberapa benturan yang terjadi sebagai sebuah dinamika kehidupan masyarakat majemuk. Namun, Agus menggarisbawahi, kelompok mana pun semestinya tak berusaha mengeliminasi identitas kelompok lainnya. Hal yang harus dilakukan adalah menempatkan identitas masing-maisng tersebut sesuai dengan porsi dan kesempatannya.

Pembicara dari kalangan aktivis media, Tommy, lebih banyak menyoroti persoalan media di dalam kasus-kasus kekerasan agama. Ia menyebutkan, media harus terlibat aktif dalam resolusi konflik dengan menampilkan fakta-fakta sekaligus membuka peluang untuk dialog. Menurt Tommy, media memiliki kemampuan untuk membangun opini publik atau “framing” peristiwa dengan sudut pandang tertentu. Akan tetapi, ia mengingatkan, tantangan awak media di lapangan juga cukup besar. Tak jarang para awak media ini menjadi sasaran kecurigaan pihak-pihak yang sedang berkonflik. Sehingga, kehadiran mereka di wilayah konflik terkadang mendapatkan penolakan. Ini tentu akan menghambat proses pengambilan data sebagai sumber berita secara utuh dan berimbang. Selain itu, tak jarang pula awak media menjadi korban kekerasan dalam sebuah konflik, baik disengaja maupun tidak.

Masalah lainnya yang kerap dihadapi media adalah persoalan keredaksian. Tak jarang , sebuah berita gagal terbit lantaran kebijakan redaksi yang tidak menginginkan memuat hasil liputan tentang konflik beragama sebab dirasa membahayakan maupun teknis penulisan berita yang membuat media menjadi seolah berpihak dan tendensius. Alih-alih dapat menjadi bagian dari solusi, justru media malah menjadi pihak yang ikut memprovokasi. Di dalam beberapa kasus bahkan reaksi publik atas suatu pemberitaan kekerasan agama kerap menjadi bumerang bagi media itu sendiri. Tak jarang kelompok-kelompok tertentu datang dan mengintimidasi kantor sebuah media akibat adanya pemberitaan yang dianggap merugikan pihak mereka.

Di dalam sesi tanya jawab pada acara yang dimoderatori oleh Siti Aminah dari Interfidei tersebut, terungkaplah beberapa pertanyaan dan fakta-fakta lain di lapangan yang dikemukakan oleh para peserta yang hadir. Masriyah, misalnya, menyebutkan Yogyakarta semakin intoleran terhadap minoritas. Bahkan, menurut aktivis Fatayat ini, pendidikan multikultural atau keragaman di wilayah dunia pendidikan formal hampir dapat dikatakan tidak ada. Di dalam hal ini, ia memberi contoh nyata yang dialaminya saat akan mendaftarkan anaknya sekolah ke salah satu SD negeri di Yogyakarta. Pada saat ia mendaftarkan anaknya, ia diwanti-wanti oleh pihak sekolah agar sang anak yang saat itu hanya menggunakan kaos dan celana panjang jeans untuk dipakaikan rok dan jilbab saat nanti sudah masuk sekolah, sebab ia seorang muslimah. Penyeragaman dan pembedaan yang dilakukan semacam ini sejak dini, menurutnya, memungkinkan seseorang bertindak intoleran di masa depan sebab ia tidak terbiasa dengan perbedaan dan keragaman. Selain itu, ia juga menyayangkan sebab hal tersebut terjadi di SD yang notabene berstatus sekolah negeri, bukan sekolah Islam. Padahal, seharusnya sekolah negeri bersikap lebih netral dan mampu menerima serta menanamkan sikap toleransi terhadap keragaman yang ada.

Di dalam kesempatan ini, Masriyah juga mempertanyakan sikap aparat yang menurutnya kerap bersikap lembek atau bahkan seolah melakukan pembiaran terhadap perilaku intoleransi. Pertanyaan senada juga diungkapkan oleh Isna dari Gusdurian Yogyakarta. Mahasiswi UIN Sunan Kalijaga tersebut menyayangkan sikap aparat yang terkesan permisif terhadap aksi-aksi intoleran yang terjadi di Yogyakarta, padahal identitas para pelaku sangat mudah dikenali.

Di dalam kesempatan ini, Masriyah juga mempertanyakan sikap aparat yang menurutnya kerap bersikap lembek atau bahkan seolah melakukan pembiaran terhadap perilaku intoleransi. Pertanyaan senada juga diungkapkan oleh Isna dari Gusdurian Yogyakarta. Mahasiswi UIN Sunan Kalijaga tersebut menyayangkan sikap aparat yang terkesan permisif terhadap aksi-aksi intoleran yang terjadi di Yogyakarta, padahal identitas para pelaku sangat mudah dikenali.

Sebagai tambahan komentar mengenai sikap aparat ini, Agnes dari Aliansi Nasional Bhineka Tunggal Ika menyebutkan bahwa seharusnya aparat bersikap tegas dengan melakukan tindakan nyata di dalam menangani kasus-kasus intoleran ini. Ia mencontohkan bahwa pada tahun 2014 dan 2015, ada banyak spanduk provokatif yang merupakan syiar kebencian terhadap kelompok tertentu. Menurutnya, aparat semestinya menindak tegas para pelaku pemasang spanduk tersebut sebab meresahkan. Selain itu, Agnes juga mempertanyakan persoalan penutupan beberapa rumah ibadah secara paksa oleh ormas tertentu. Ia mempertanyakan apakah memang masyarakat umum berhak melakukan penutupan rumah ibadah atau tidak.

Menanggapi beberapa pertanyaan tersebut, Noorhaidi menjawab bahwa pendidikan multikultural sangat perlu dikembangkan, terutama di sekolah-sekolah. Hal itu dapat dimanifestasikan di dalam berbagai program yang sesuai dengan tingkatan pendidikan yang ada. Selain itu, ia mengatakan bahwa kegagalan melakukan sebuah sistem secara substantif oleh pemegang kebijakan hendaklah diatasi dengan cara mengurai masalahnya, bukan malah diatasi dengan cara penyeragaman. Mengenai peran aparat kepolisian, Noorhaidi mengatakan bahwa polisi memang seharusnya tidak usah takut untuk menindak para pelaku tindakan intoleran selama tak menggunakan cara-cara represif. Sebab jika dibiarkan, hal ini akan mencoreng wibawa negara dan mengarah pada gejala privatisasi kekerasan, membiarkan kekerasan dilakukan oleh sekelompok orang sipil. Padahal, privatisasi kekerasan ini adalah sebuah sinyalemen akan lemahnya negara. Di dalam hal ini, Noorhaidi juga menyebutkan bahwa privatisasi kekerasan ini juga dapat menjadi indikasi akan adanya kepentingan politik dari pihak tertentu. Misalnya ada aktor politik yang sengaja melindungi kelompok-kelompok intoleran tertentu guna mendapatkan dukungan suara dan kekuasaan dari kelompok tersebut. Namun, di akhir penjelasannya, ia kembali menegaskan bahwa penegak hukum harus tetap bertindak sesuai proporsi dan kewenangannya. Polisi lebih kuat dari kelompok radikal, jadi seharusnya tidak boleh ada toleransi terhadap kelompok-kelompok pelaku intoleran.

Di lain pihak Agus menyebutkan bahwa kemungkinan penyebab tidak adanya tidakan dari polisi atas para pelaku intoleran itu adalah tidak adanya cukup bukti. Karenanya, ia menghimbau agar laporan akan adanya tindakan intoleran juga disertai bukti-bukti yang cukup, jangan hanya berbentuk laporan semata. Hal ini akan membantu aparat dalam menegakkan hukum yang seharusnya. Selain itu, ia juga meminta masyarakat memaklumi akan kinerja aparat yang mungkin terlihat agak lamban sebab banyaknya kasus yang harus diselesaikan sedangkan jumlah SDM yang dimiliki masih terbatas.

Pertemuan ini akhirnya ditutup oleh tanggapan dari pihak kepolisian, diwakili oleh beberapa anggota polisi yang hadir pada saat itu. Pihak polisi mengakui bahwa memang ada banyak kendala yang harus mereka hadapi di lapangan di dalam penuntasan kasus-kasus kekerasan agama dan tindakan intoleran lainnya. Namun, mereka senantiasa berusaha melakukan penanganan terbaik agar tidak kontraproduktif. Selain itu, polisi juga mengingatkan bahwa peran serta masyarakat di dalam penyelesaian kasus-kasus kekerasan agama ini sangatlah dibutuhkan. Karenanya, pihak kepolisian mengimbau agar masyarakat tidak segan-segan melaporkan atau membantu polisi di dalam menghadapi persoalan intoleransi yang hadir.

Hadirnya Babinsa dan Babinkamtibmas di setiap wilayah di Yogyakarta hendaklah dimanfaatkan dengan sebaik-baiknya oleh masyarakat untuk membantu kepolisian di dalam kasus-kasus tindakan intoleran. Sehingga, tindakan preventif dapat dilakukan secara bersama-sama oleh pihak kepolisan dan masyarakat. Sebab, menciptakan kehidupan yang rukun dan damai adalah tanggung jawab bersama seluruh elemen masyarakat dan pemerintahan Indonesia, bukan hanya tanggung jawab salah satu pihak saja.

Editor: Azis Anwar Fachrudin