The Disengagement of Jihadists in Poso

Afifurrochman Sya’rani – 27 March 2018

The founder and director of the Center for the Study of Religion and Democracy (PUSAD) Paramadina, Ihsan Ali-Fauzi gave presentation at the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on February, 21, 2018, about the disengagement of jihadists in Poso, Central Sulawesi.

In the beginning of his presentation, Ali-Fauzi clarified what he meant by the term “disengagement” in contrast to the term “deradicalization” which is more popular. The former refers to “a decision by individual members of a terror group, radical movement, or gang to cease participation in acts of violence physically or psychologically”. The latter refers to “the delegitimation of the ideological principles that underpin the behavior”. Thus, while disengagement focuses on “a gradual process of internal reflection” to disengage from terrorism, deradicalization focuses on a process of eliminating ideologies underlying terrorism. Ali-Fauzi therefore contended that it is possible that a person “may disengage without fully deradicalized”.

According to Ali-Fauzi, Poso remains a unique case of study in comparison to other regions that suffered from communal conflict such as Ambon, North Maluku, and West Kalimantan. The arrival and infiltration of terrorist groups, such as Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) and Mujahidin KOMPAK, had transformed Poso from communal conflict (1998-2002) into terrorism (2002-2007). Besides, it is now possible to get access of information from both ex-jihadists who have disengaged from terrorism and those in prison who have not, while it was impossible before 2010.

Based on field research in Jakarta and Central Sulawesi and interviews with 23 current and former Poso-based jihadists, Ali-Fauzi presented three driving factors that lead to the disengagement of jihadists from violent extremism in Poso.

First, structural factors. The role of the state, especially the police, to eradicate terrorism in Poso has led jihadists to take into account the cost and benefit of conducting violent attacks. They do realize that contemporary situation of Poso is different from that in the past. There is no longer communal conflict between Muslims and Christians.

Second, push factors. The jihadists have started to doubt the ideology, leaders of their groups, and benefits of conducting violent attacks. This, in turn, leads them to rethink and reassess both their involvement in jihadist groups and the use of violence for societal change.

Third, pull factors. Pressures from jihadists’ spouse and parents have significantly contributed to their disengagement. Their encounter and “inter-personal relationship” with people outside their circle contribute to their rethinking and disengagement from violent extremism. Also, they have changed their “personal and professional priorities”. Being a jihadist is no longer important. Some of them are now busy with their jobs, for the sake of fulfilling their family needs.

In his presentation, Ali-Fauzi was also critical of the role of the state in countering violent extremism. “The role of the state and law enforcement has been ad hoc and inconsistent at best. This inconsistency has undermined the state’s ability to play a meaningful role in the disengagement of jihadists in Poso,” he stated. Although the state is likely to employ a humanist approach in its law enforcement efforts, the use of violence has nevertheless impeded them such as the case of Basri, a Poso terrorist.

Ali-Fauzi further told about the story of Arifuddin Lako, well known as Iin Brur, an ex-Poso jihadist. His radicalization began during the communal conflict in Poso. Many of his family members and friends were murdered. This drove Iin Brur to join Laskar Jihad for revenge. When the police did a massive combat of terrorism in Poso from 2007 to 2009, he was hiding. Some of his jihadist friends died, while some others were arrested. From his hideout, Iin Brur got news from television that jihadists in Poso were increasingly arrested by the Indonesian Special Detachment 88 (Densus 88). Since then, he was encouraged to reflect whether he would surrender himself to the police or not. This was the first moment leading to his disengagement. Finally, on November, 18, 2009, he voluntarily surrendered himself to the police.

According to Ali-Fauzi, the most profound factors that drive Iin Brur to psychologically and physically disengage from violent extremism is the pressure from his mother. From his hideout, he had been aware for a long time that his mother was eager that he would surrender himself to the police soon. He was also thinking about the future of his siblings. Yet, Ali-Fauzi contended that Iin Brur’s encounter and “inter-personal” relationship with people outside his jihadist circle contributed more to his disengagement. Adriany Badrah and Maskur, a married couple, whom Iin Brur knew as his guest house during hiding, frequently encouraged him to disengage from extremism. Iin Brur remembered that he was convinced that the communal conflict in Poso was more generated by revenge motives rather than religious motives.

Being released from prison on April 2015, Iin Brur has been very active in conducting peacebuilding activities in Poso. In the midst of 2016, he and his ex-jihadist friends successfully built Rumah Katu Marine Park (Taman Laut Rumah Katu) located at Madale beach, 10 km from the center of the city. On August, 19-20, 2016, Iin Brur and Rumah Katu Marine Park held what they called “one of the biggest sea festivals in Poso”.

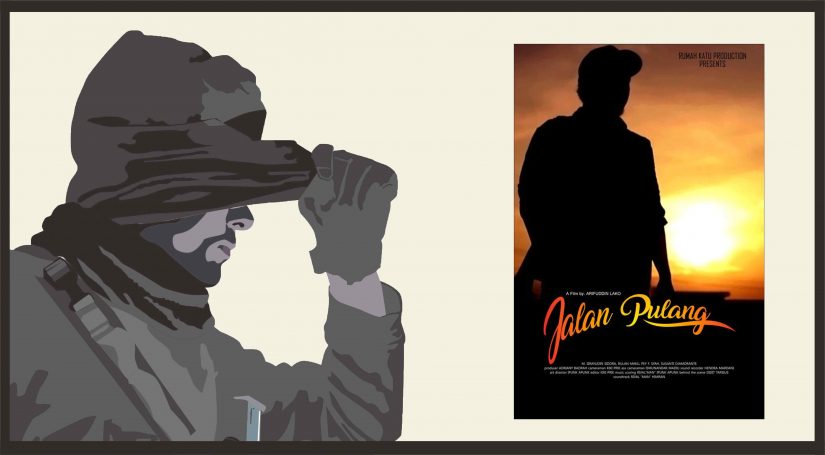

Unfortunately, because of some problems, “Rumah Katu Marine Park” was not well-established. Since then, Iin Brur has focused on developing and strengthening “Komunitas Rumah Katu”, a Poso-based organization that aims to maintain and promote peace. This organization involves victims of the communal conflict, both Muslims and Christians. Iin Brur himself serves as the chief of the organization. On October 2017, thanks to local government and NGOs, he directed Jalan Pulang, a movie based on the story of his and his friends’ experience as ex-jihadists. Supported by local elites, the movie was first launched in Tentena and Poso city.

During the Q&A session, a participant asked about the ideological factor driving jihadists’ radicalization. Ali-Fauzi argued that ideological factor is misleading in understanding both the radicalization and disengagement of jihadists in Poso. In fact, most of them were radicalized because of their desire for vengeance instead of theological indoctrination. This may explain why using theological approach for deradicalization has frequently failed.

___________

Afifurrochman Sya’rani is CRCS student of the 2017 batch.