Selama berabad-abad budaya dan masyarakat Tionghoa telah hadir, melebur, dan menjadi bagian tak terpisahkan dari sejarah peradaban Nusantara. Jejak-jejak dinamika tersebut tersimpan dalam berbagai arsip seperti koran, surat, dan buku. Upaya penyelamatan arsip berarti membuka kembali ruang bagi narasi kebangsaan yang lebih inklusif.

Berita

Perdebatan tentang sains, agama, dan tradisi merupakan pergulatan yang sangat panjang dalam sejarah peradaban manusia. Upaya merefleksikan dan memosisikan diri menjadi bagian penting dalam memahami makna dan hakikat pengetahuan bagi kehidupan manusia.

Kemunculan kredit pada film bukanlah sebuah akhir, melainkan sebuah ajakan bagi kita, yang ada di seberang layar, untuk menyambung apa yang film itu perjuangkan.

Narasi sejarah sering menghilangkan peran perempuan, kaum trans, dan masyarakat adat. Padahal, mereka berkontribusi besar dalam perjuangan sosial, budaya, dan kemanusiaan.

Industri, korporasi, bahkan lembaga negara berlomba-lomba membingkai diri sebagai bagian dari gerakan hijau. Seolah, dengan menyebut sesuatu yang hijau, seluruh proses di baliknya otomatis menjadi ekologis nan lestari.

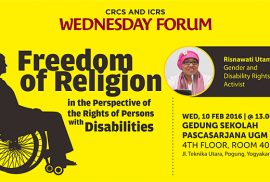

Segregasi antara kerja akademik dan aktivisme seringkali digambarkan terpisah oleh garis batas yang saling mengelakkan. Kerja akademik dianggap harus objektif dan netral, sementara aktivisme bersifat subjektif dan politis. Karakteristik yang berlawanan itu membuat anggapan keduanya mesti dipisahkan dalam ruang lingkupnya masing-masing. Anggapan ini coba dikritisi oleh para alumni CRCS UGM berdasar kiprah mereka dalam dunia aktivisme dari berbagai latar belakang.

Kendati berbeda cara, tiap doa dari masing-masing pemuka agama bertujuan sama: pemulihan bangsa Indonesia dari konflik berkepanjangan serta harapan akan kondisi yang lebih baik lagi. Selama prosesi tersebut, massa aksi duduk tenang seraya mengindahkan tiap untaian doa. Agama dengan caranya sendiri tengah mengadvokasi berbagai isu yang terjadi di masyarakat.

Fellowship KBB 2025 kali ini menghadirkan kelas Klinik dan Advokasi KBB sebagai bagian dari luaran yang tidak hanya menghasilkan gagasan tertulis, tetapi juga aksi nyata.

Selama ini KUHP 2023 yang akan efektif berlaku tahun depan ini jarang dibicarakan di akar rumput. Padahal, masyarakat awamlah—terutama dari kelompok rentan keagamaan—yang akan terpengaruh secara signifikan.

Karakter dari KUHP itu adalah membatasi hak. Yang menjadi perhatian ialah bagaimana pembatasan itu tidak melanggar hak warganegara, terutama dalam hal beragama atau berkeyakinan.

Kain tenun bukan sekadar selembar sandangan. Setiap lembarnya mewakili relasi simbolik antara makna dan kesimbangan nilai kehidupan pembuatnya.

Dalam KUHP 2023, bab agama atau kepercayaan mendapat ruang tersendiri melalui pasal 300—305. Penafsiran yang tepat terhadap isi pasal-pasal tersebut menjadi langkah vital agar implementasinya relevan dengan realitas sosial masyarakat dan pemajuan hak asasi manusia.

Kendati bukan negara agama, Indonesia menempatkan agama sebagai salah satu pilar penting dalam kehidupan sosial dan bernegara. Dengan kata lain, keberadaan agama perlu dilindungi oleh negara. Namun, sebelum 2023, KUHP yang dipunyai Indonesia merupakan warisan negara sekuler Belanda sehingga agama tidak mendapatkan tempat dalam undang-undang tersebut. Karenanya, sejak Seminar Hukum Nasional I 1963 ada keinginan kuat untuk memiliki “delik agama” dalam suatu KUHP Nasional.

Betapa pun berbeda pengalaman dan pandangan religius dengan generasi pendahulunya, anak muda Khonghucu tak akan pernah tercerabut dari “tulang” leluhurnya.

Transpuan dan Hak Demokrasi yang Terabaikan

Nita Amriani – 11 November 2024

Apakah seorang transpuan lahir hanya untuk mengecap pedihnya bayang-bayang persekusi dan menjadi pelengkap suara pemilu?

Diskriminasi dan stigma berlapis menyingkirkan kelompok transpuan dari hak-hak dasar sebagai warga negara. Banyak transpuan sulit mengakses pekerjaan dan hidup dalam ancaman persekusi. Di sisi lain, mereka juga tak lagi punya ruang aman di rumah karena keluarga mereka tidak lagi mau menerimanya. Bagi kelompok transpuan, konsep keadilan dalam sila ke-5 Pancasila masih jauh api dari panggang.

Suara Masyarakat Adat di Tengah Bayang-Bayang Demokrasi

Vikry Reinaldo Paais – 06 November 2024

Pembangunan nasional yang diklaim oleh pejabat pemerintahan sebagai sarana untuk meningkatkan kesejahteraan sosial justru merampas, mengkriminalisasi, serta mengeksklusi hak-hak hidup masyarakat adat dan penganut agama leluhur. Hutan dan tanah mereka dirampas oleh negara untuk dijadikan kawasan produksi maupun konservasi. Ketika masyarakat adat berjuang mempertahankan hak atas tanahnya, mereka justru dikriminalisasi oleh aparat negara. Dalam konteks sosio-religius, sebagian besar masyarakat maupun pemimpin agama menstigma masyarakat adat sebagai belum beradab, masih primitif, serta belum beragama sehingga harus dimodernkan dan diagamakan. Problematika ini adalah tantangan serius dalam konteks Indonesia yang mengumandangkan demokrasi sebagai sistem pemerintahan dan prinsip hidup berbangsa dan bernegara. Isu-isu krusial ini menjadi bahasan utama dalam perhelatan International Conference and Consolidation on Indigenous Religion (ICIR) ke-6 pada 22-25 Oktober 2024 di Ambon.

Transformasi Modernitas yang Berlantas di Kanekes

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 15 Oktober 2024

Modernitas membawa tantangan bagi masyarakat Urang Kanekes. Namun, mereka punya cara tersendiri dalam menghadapinya.

Masyarakat adat Urang Kanekes—atau yang lebih populer dengan nama Baduy—di Banten selalu menarik perhatian para peneliti. Setidaknya ada 95 dokumen karya ilmiah yang memuat kata kunci “Baduy” dan 23 dokumen karya ilmiah dengan kata kunci “Kanekes” di situs Scopus. Ketertarikan ini muncul, di antaranya, karena masyarakat adat Kanekes sangat melestarikan ajaran tradisi leluhur sampai hari ini kendati wilayah adat mereka tidak jauh dari Jakarta, kota metropolitan serba modern.

Kedai kopi yang dianggap sekadar tempat transaksi ekonomi, ternyata menjadi ruang penting terciptanya sebuah dinamika relasi lintas etnis dan agama yang sarat akan luka masa lalu.

Ambiguitas dan Toleransi dalam Tradisi Masyarakat Muslim

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 25 September 2024

Sepanjang sejarah peradaban Islam, perdebatan tafsir selalu hadir dengan saling menghargai perbedaan pendapat.

Realitas pemahaman dan praktik ajaran Islam sebagai aturan universal masih ambigu. Meski tuntunannya termaktub dalam pegangan dasar—Al-Qur’an dan hadis—interpretasinya selalu terbuka untuk dibahas dari perspektif dan ideologi tertentu. Cendekiawan dan ulama kerap berbeda paham atas interpretasi ajaran Islam sehingga mendorong terbentuknya ragam tafsir dan tarekat dalam Islam.

Dari Nurani Jadi Aksi

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 15 September 2024

Sebagian umat beragama menyadari gejala alam yang tidak menentu sebagai fenomena perubahan iklim. Lantas, sejauh mana pengetahuan agama mendorong umatnya melakukan kegiatan yang mendukung lingkungan?

“Agama memiliki efek ganda dalam membentuk perilaku ramah lingkungan,” jelas Iin Halimatusa’diyah, Direktur Riset Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat (PPIM) UIN Jakarta, lewat presentasinya bertajuk “From Belief to Action: Religious Values and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Indonesia” dalam Wednesday Forum (4/9).

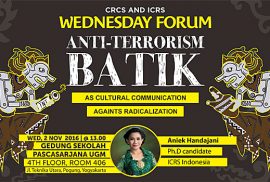

berdasarkan data dari Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC), Bima merupakan daerah dengan rekam jejak aktivitas terorisme yang tinggi. Lantas, karakteristik keagamaan seperti apa yang tengah berkembang di antara masyarakat Bima? Sejauh mana karakteristik keagamaan itu mempengaruhi perkembangan terorisme di Bima?

Meneroka Diplomasi Buddhis dalam Sejarah Asia Modern

Yulianti – 20 Agustus 2024

Dalam sejarah kolonialisme di Asia modern, jejaring dan aliansi tidak hanya terjadi melalui jaringan negara kolonial, tetapi juga aliansi kelompok masyarakat yang ada di dalamnya. Salah satu bentuk aliansi yang berperan penting dalam geopolitik tersebut ialah diplomasi buddhis.

Dinamika tersebut menjadi bahasan utama dalam panel “Friends in Dharma: Buddhist Diplomacy and Transregional Connection in Modern Asia”. Panel ini merupakan bagian dari kluster tema Inter Area/Border Crossing pada “AAS in ASIA Conference”di Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia pada 9–11 Juli 2024. Mengambil latar belakang sejarah Asia modern, panel Buddhist Diplomacy ini memfokuskan kajian pada kiprah komunitas agama yang berasal dari kalangan yang berbeda-beda dalam membentuk jaringan, aliansi, dan kerja sama di Asia pada pertengahan abad ke-20 sampai ke-21. Jaringan dan hubungan-hubungan kelompok inilah yang kemudian dimaknai sebagai buddhist diplomacy (diplomasi buddhis) yang melibatkan individu, kelompok, dan negara-negara buddhis di Asia. Keberadaan diplomasi buddhis ini mempengaruhi hubungan transregional dan pertukaran budaya dari abad ke-20 hingga abad ke-21 di Asia.

Memulihkan Literasi Agama-Agama Tionghoa

Rezza Maulana – 12 Januari 2024

By breadth of reading and the ties of courtesy, a gentleman is kept, too, from false paths (Confucius)

Eksistensi dan kiprah masyarakat keturunan Tionghoa dalam derap sejarah Nusantara seakan tenggelam oleh stigma negatif yang menyelimutinya. Padahal, dinamika pemikiran dan pergulatan mereka ikut menyumbang batu bata dalam bangunan negeri yang bernama Indonesia ini. Salah satu penyebabnya ialah minimnya kajian yang bersumber dari sudut pandang masyarakat keturunan Tionghoa itu sendiri. Kebijakan asimilasi, represi, dan aksi amuk massa yang kerap menyasar komunitas keturunan Tionghoa ikut menyumbang hilangnya berbagai dokumen penting dan sumber sejarah. Untungnya, di samping koleksi pribadi atau perorangan, beberapa arsip sejarah yang tersimpan di klenteng atau rumah ibadah masih terselamatkan.

Beasiswa S2 Kerja Sama Diktis Kemenag dan CRCS UGM. Waktu pendaftaran: 3 Mei - 4 Juli 2019.

Esai foto dari ibadah dan perayaan Natal di GKJ, GPIB, GKI, dan HKBP Yogyakarta, 24 Desember 2018.

Mahkamah Konstitusi: Pengosongan Kolom Agama bagi Penghayat Kepercayaan Bertentangan dengan UUD 1945

MK mengabulkan permohonan uji materi terkait aturan pengosongan kolom agama bagi penghayat kepercayaan di KK dan KTP.

A report of the first day of the workshop on the institutionalization of interfaith mediation with Imam Ashafa and Pastor Wuye at UGM.

Liputan dari hari ketiga bersama Jacky Manuputty dalam rangkaian kuliah umum "Imam & Pastor" dan lokakarya Pelembagaan Mediasi Antariman.

A. S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Liputan

Hadirnya kelompok-kelompok radikal-intoleran yang kerap melakukan kekerasan atas nama agama adalah suatu tantangan iman. Dalam menghadapi kelompok ini, umat beriman semestinya tidak membalasnya dengan kekerasan yang serupa, tetapi harus dengan cara-cara yang selayaknya dilakukan orang beriman, yakni cara yang penuh kasih dan kelembutan.

Itulah di antara yang diungkapkan Kardinal Julius Darmaatmadja, SJ, dalam seminar nasional bertajuk Merajut Persaudaraan, Mengikis Sikap Intoleran yang dihelat di Fakultas Teologi Universitas Sanata Dharma pada 16 Mei 2017. “Yang paling membuat tantangan iman semakin besar di dalam diri kita adalah kalau yang menjadi marah besar itu kita sendiri. Itu tantangan iman untuk diri kita sendiri,” ungkapnya

Oleh sebab itu, menurut Romo Kardinal, gejala arus balik yang tengah terjadi di masyarakat akhir-akhir ini atas perilaku kelompok radikal itu hendaklah pula diwaspadai agar tidak melenceng dari batas-batas yang telah ditentukan negara dan diajarkan agama. Perlawanan atas perilaku intoleran dan kekerasan dari kelompok radikal mesti tetap mengedepankan Pancasila, keutuhan NKRI, dan menjunjung tinggi kebinekaan.

Dalam hal ini, Romo Kardinal menyatakan apresiasi terhadap Muhammadiyah dan Nahdlatul Ulama yang konsisten menjaga persaudaraan di antara umat beragama dan menegaskan bahwa Islam harus menjadi rahmat bagi semua, rahmat bagi seluruh ciptaan Tuhan. “Saya tersentuh saat pimpinan Muhammadiyah, Haidar Nashir, menyampaikan khotbah pada perayaan Idul Adha yang berjudul Menyembelih Egoisme, Merayakan Solidaritas,” ujar Romo Kardinal. Ia kemudian menyitir beberapa bagian dari khotbah Haidar Nashir tersebut yang dimuat Kompas, 11 September 2016. Menurut beliau, sikap altruis yang disebut-sebut oleh Haidar Nashir di dalam khotbahnya itu akan melahirkan sikap kasih kepada sesama tanpa sekat agama, suku, ras, dan golongan.

Terhadap umat Katolik dan Protestan, Kardinal Darmaatmadja menyerukan untuk tetap mengutamakan kasih atas sesama seperti mengasihi diri sendiri. Sebab, mengutip Yohanes, kasih kepada Tuhan harus dibuktikan lewat mengasihi sesama. “Karena barangsiapa yang tidak mengasihi saudaranya yang dilihatnya, maka tidak mungkin mengasihi Allah yang tak dilihatnya,” ujarnya menegaskan.

Menutup ceramahnya, Romo Kardinal menegaskan kembali pernyataanya. “Kita tegakkan negara kita berdasarkan Pancasila; kita perkokoh NKRI dan persaudaraan nasional. Namun, sikap kita yang inklusif tetap perlu dipertahankan selalu, terhadap kelompok yang radikal pun. Hukum balas-membalas tidak boleh dilakukan oleh orang beriman. Sebaliknya, kita tetap memegang teguh sikap mengasihi dan mengampuni. Kita ampuni orangnya meski kita menolak perbuatannya.”

Menanggapi Romo Kardinal, Buya Syafi’i Ma’arif sebagai pembicara selanjutnya mengatakan bahwa apa yang dikatakan oleh Romo Kardinal itu, terutama dalam soal kasih, persis seperti ajaran Islam di dalam mengasihi sesama. “Apa yang disampaikan Kardinal itu seperti suara seorang muslim yang belum terkontaminasi.”

Buya Syafi’i menegaskan bahwa Islam sebagai rahmatan lil alamin itu universal bagi seluruh umat manusia. Kemunculan kelompok Islam radikal yang kerap melakukan kekerasan seperti itu disebabkan mereka terjebak dalam lingkaran—yang disebut Buya Syafi’i sebagai—“misguided arabism” yang sudah berlangsung berabad-abad dan membuat peradaban umat Islam—khususnya di wilayah Timur Tengah saat ini—porak poranda.

“Yang berlaku di dunia Arab sekarang ini adalah peradaban Arab yang sudah bangkrut,” tegas Buya Syafi’i. Celakanya, peradaban yang bangkrut ini dicoba untuk dibawa ke Indonesia oleh kelompok-kelompok tertentu. Tak heran jika isu sektarian yang menjadi pemicu perpecahan umat Islam di dunia Arab sana juga mulai muncul dan berkembang di Indonesia saat ini.

Buya Syafi’i menyebutkan bahwa perilaku kekerasan kelompok radikal itu muncul dikarenakan mereka mengadopsi teologi maut. “Teologi maut ini keluar dari perasaan keputusasaan. Hopeless. Tidak berdaya. Kalah. Kalau sudah kalah, ujungnya kalap,” ucapnya. Akibatnya, tak sedikit umat Islam yang akhirnya lebih memilih pindah ke negara-negara mayoritas nonmuslim, sebab di sana dirasa lebih aman dan nyaman untuk mengekspresikan diri. Sedangkan di kampung halamannya, mereka diberangus.

Pembicara ketiga, Widiyono, tokoh dari umat Buddha dan juga alumnus CRCS, menegaskan bahwa agar tidak terjebak dalam radikalisme, setiap kita mesti menyadari akan niscayanya sebuah keragaman. Kesadaran akan saling keterikatan di dalam keragaman dan bukannya saling bermusuhan sangat dibutuhkan. Di dalam ajaran Buddha, menurutnya, kesadaran akan keragaman dan saling keterhubungan di antara segala hal disebut dengan paticcasamuppada. Hilangnya kesadaran akan hal ini akan melahirkan sikap permusuhan dan tindak kekerasan yang nyata, seperti yang dapat disaksikan pada perilaku sekelompok penganut agama Budha di Sri Lanka atau Myanmar. Menurutnya, tanpa keragaman tak akan ada kehidupan.

Pembicara keempat, Romo Mateus Purwatma dari Katolik, menegaskan bahwa agar tidak terjebak dalam radikalisme ini, seorang Katolik harus menjadi misioner, menjadi seorang saksi, yakni mengamalkan ajaran Yesus di tengah masyarakat beriman secara cerdas, mengerti apa yang diimani dan dapat membaca Alkitab secara benar. Menurutnya, kemampuan membaca Alkitab secara benar ini sangatlah penting, agar saat berjumpa dengan ayat-ayat yang mengekslusikan yang lain tidak terjebak dalam pembacaan yang kaku, sehingga tak salah mengerti. Selain itu, Romo Mateus melanjutkan, seorang Katolik juga mesti menyadari bahwa ia beriman dalam konteks masyarakat majemuk, sehingga saat ia berjumpa dengan orang dari agama lain, ia tahu bagaimana cara menempatkan keimanannya di sana.

*A. S. Sudjatna adalah mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2015.

Beasiswa bebas SPP di CRCS untuk alumni perguruan tinggi non-Islam.

“Gereja-gereja memahami perdamaian secara sempit, sekadar sebagai negative peace. Perdamaian dianggap tercapai apabila tidak ada konflik.”

Pada hari Senin, 22 Mei 2017, Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) mengumandangkan deklarasi meneguhkan kembali Pancasila. Termasuk dalam rangkaian acara adalah sarasehan dan FGD bersama akademisi dan budayawan.

A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Liputan

“Tidak banyak orang yang berpikir bahwa ada ‘Islam Tuhan’ dan ada ‘Islam manusia’. Kebanyakan orang selama ini berpikir bahwa Islam itu, ya, hanya Islamnya Tuhan.” Demikian ungkap Dr. Haidar Bagir di awal peluncuran buku terbarunya yang berjudul Islam Tuhan Islam Manusia: Agama dan Spiritualitas di Zaman Kacau (Mizan, 2017) pada Jumat, 7 April 2017. Acara bedah buku ini diadakan oleh Laboratorium Studi al-Quran dan Hadis (LSQH) di Convention Hall UIN Sunan Kalijaga.

Membuka diskusi, Dr. Haidar Bagir menjelaskan dua dari sekian alasan yang membuatnya memilih judul bagi karya yang menjadi penanda ulang tahunnya yang keenampuluh itu. Pertama, menurutnya, Islam yang kini dipahami oleh seluruh muslim adalah “Islamnya manusia”, bukan Islamnya Tuhan. Artinya, apa yang dipahami oleh setiap muslim saat ini sebagai Islam atau ajaran Islam adalah keislaman yang sudah melalui proses tertentu, yakni melewati saringan otak dan hati masing-masing individu, yang tentu saja tidak kosong dari beragam faktor, termasuk nafsu di dalamnya. Karenanya, ia berbeda dengan Islam yang seutuhnya dikehendaki Tuhan. Dalam hal ini, manusia hanyalah berupaya untuk memahami Islam untuk sedapat mungkin mendekati yang dimaui Tuhan.

Dengan memahami hal ini, menurut Dr. Haidar, siapapun akan sadar bahwa setiap muslim, sepintar dan sealim apa pun, tetap memiliki peluang kesalahan sekecil apa pun di dalam pehamanan keislamannya. Tidak ada seorang pun—selain Rasulullah Saw.—dari barisan umat Islam yang pemahaman keislamannya itu mutlak betul. Dalam pandangan Dr. Haidar, jika ada orang yang menganggap bahwa hanya pemahaman keislamannyalah yang mutlak benar sedangkan yang lain mutlak salah, dia telah menempatkan dirinya sebagai Tuhan atau wakil Rasulullah.

Seharusnya, lanjut Dr. Haidar, kita belajar kepada para imam mazhab seperti Imam Syafi’i atau Imam Malik yang secara sadar mengatakan bahwa pendapatnya adalah pendapat yang benar namun tetap berpeluang salah; dan pendapat yang lain salah namun tetap berpeluang benar. Dengan begitu, siapapun tak akan berupaya memonopoli kebenaran. “Sekarang enggak; kalau melawan pendapat saya, berarti melawan Tuhan!” ujar Dr. Haidar mengungkapkan kesedihannya atas sekelompok umat Islam yang kerap menuduh sesat muslim lain dari luar golongannya.

Dr. Haidar juga menjelaskan bahwa ada kemungkinan untuk muncul lebih dari satu tafsir yang sama-sama benar dalam memahami kitab suci. Ini karena adanya sudut pandang atau pendekatan yang berbeda dalam membacanya. Menjelaskan ini, Dr. Haidar menggunakan analogi piramida: “Kalau kita lihat sejajar mata, maka tampak segitiga; kalau lihat dasarnya, maka segi empat; kalau dari atas lurus, maka jadilah seperti titik.” Perbedaan pandangan ini bukanlah sebentuk kekeliruan, namun parsialitas. Menguatkan pandangannya, Dr. Haidar menyitir ucapan Rumi bahwa kebenaran itu laiknya cermin yang jatuh ke bumi dan pecah berkeping-keping, lalu setiap orang mengambil satu kepingannya.

Alasan kedua memilih judul tersebut adalah bahwa Islam, menurut Dr. Haidar, diturunkan untuk manusia, bukan untuk Tuhan. Agama adalah seperangkat ajaran yang diturunkan demi kebaikan manusia. Di antara cara untuk itu, Dr. Haidar menekankan, adalah dengan menginternalisasi sifat Tuhan yang secara khusus tercantum dalam ucapan basmalah: ar-Rahman dan ar-Rahim. Orang Islam yang baik adalah orang yang menghabiskan hidupnya menebar kasih sayang ke semua manusia, menjadi agen rahman-rahim. Dan adalah keanehan, jika ada orang yang mendaku membela Tuhan namun begitu bernafsu membinasakan manusia, seolah-olah semakin banyak membunuh semakin ia mendapat rida Tuhan.

Di tengah-tengah diskusi, Dr. Haidar mengutarakan beberapa hal terkait isi buku setebal 288 halaman itu. Di antara yang sempat ditekankannya ialah tentang sejarah perang Nabi. Karena ada banyak narasi peperangan tertulis dalam literatur sirah Nabi, beberapa orang mengira bahwa perang adalah bagian esensial dari agama Islam. Padahal, jika dijumlah hari-hari yang digunakan Nabi untuk berperang, paling hanya dua tahun lebih sedikit saja dari total 23 tahun kerasulan beliau. “Bahkan,” lanjut Dr. Haidar, “ada penelitian yang minimalis, yang tidak memasukkan sariyyah, sehingga jika dijumlah perangnya Nabi hanya delapan puluh hari saja.” (Catatan redaksi: Dalam terminologi literatur sirah Nabi, sariyyah adalah ekspedisi pasukan tanpa dipimpin dan tak didampingi Nabi; ini yang membedakannya dari ghazwah yang dipimpin langsung oleh Nabi.)

Jika diajarkan dengan benar, Islam sebetulnya adalah agama yang menekankan perdamaian dan cinta kasih, bukan agama peperangan dan kebencian. Menegaskan hal ini, Dr. Haidar mengutip Imam Ja’far Shadiq yang secara retoris pernah berucap, “Hal al-din illa al-hubb?” (Apalagi agama itu kalau bukan cinta?) Sejalan dengan ini ialah sabda Nabi, “Cinta adalah asas(agama)ku” (al-hubb asasi). Kalau ada perintah mempersiapkan diri untuk berperang, seperti ditemukan dalam QS al-Anfal [8]:60, menurut Dr. Haidar, itu adalah tindakan preventif menghadapi serangan kelompok lain, dan bukan ditujukan untuk tindakan ofensif.

Hal lain yang juga sempat ditekankan Dr. Haidar dalam diskusi buku ini adalah tentang istilah yang populer dipakai untuk menyebut non-muslim, yaitu “kafir”. Dr. Haidar lugas menuturkan bahwa tidak seluruh non-muslim dapat dikategorikan kafir. Non-muslim yang dapat dikategorikan kafir hanyalah non-muslim yang telah menerima dakwah Islam dan telah sangat jelas memahaminya sebagai suatu kebenaran tetapi dengan sadar memilih untuk mengingkarinya karena vested interest atau alasan lain. Hal ini berdasar pada argumen-argumen dari nash al-Quran, hadis, dan pendapat para ulama lampau yang lebih detail dijelaskan di buku itu. “Untuk menyatakan non-muslim sebagai kafir itu harus ada qiyamul-hujjah,” ungkap Dr. Haidar, “Kalau Islam yang sampai kepada mereka tidak cukup meyakinkan mereka, itu berarti hujjah belum tegak, dan karena itu bukan kafir.” Dengan ini, ia mewanti-wanti agar kita tidak mudah mengobral tuduhan sesat dan kafir kepada orang yang berbeda mazhab atau beda keyakinan.

Menutup ceramahnya, Dr. Haidar menawarkan bahwa Islam paling baik diajarkan dengan memberikan penekanan pada aspek spiritualitas. Baginya, tasawuflah yang mewadahi aspek cinta dalam Islam. “Banyak umat Islam lupa kalau Islam bukan hanya terdiri dari rukun Islam dan rukun iman. Ada rukun yang merupakan puncak keimanan dan keislaman, yaitu rukun ihsan, yang ada dalam tasawuf. Ihsan inilah yang melahirkan cinta. Hilangnya ihsan membuat keislaman seseorang menjadi kering dan penuh kebencian,” pungkas Dr. Haidar.

Penulis, A.S. Sudjatna, adalah mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2015.

A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Berita

“Terpujilah Engkau, Tuhanku, karena Saudari kami, Ibu Pertiwi, yang menyuapi dan mengasuh kami, dan menumbuhkan aneka ragam buah-buahan, beserta bunga warna-warni dan rumput-rumputan. Saudari ini sekarang menjerit karena kerusakan yang telah kita timpakan kepadanya, karena tanpa tanggung jawab kita menggunakan dan menyalahgunakan kekayaan yang telah diletakkan Allah di dalamnya.”

Begitulah Paus Fransiskus memulai bait-bait awal ensiklik keduanya. Didahului dengan ucapan “Laudato Si’, mi’ Signore,” “Terpujilah Engkau, Tuhanku,” yang ia kutip dari ucapan Santo Fransiskus dari Asisi, pendahulunya ratusan tahun lalu, Paus Fransiskus memulai penegasan sikapnya yang lahir dari refleksi keimanan atas realitas dunia yang hadir saat ini. Dua ratus empat puluh enam paragraf dari keseluruhan ensiklik ini berbicara soal bagaimana seharusnya manusia beragama dan beriman bersikap atas alam dan lingkungannya.

Ensiklik Laudato Si ini sejatinya adalah seruan profetik pemimpin tertinggi Gereja Katolik yang disandarkan pada ajaran keimanan Katolik. Sebuah ensiklik tak hanya merespons realitas sosial, namun juga mengungkapkan basis teologisnya, sehingga aksi-aksi implementatif terhadap ensiklik bukan hanya merupakan gerakan sosial melainkan juga gerakan keagamaan.

Membahas relevansi ensiklik ini dalam konteks Indonesia, Muda-Mudi Katolik (MUDIKA) Paroki Santo Antonius Kotabaru Yogyakarta mengadakan diskusi dengan judul Memandang Petani Kendeng dengan Ensiklik Laudato Si pada Selasa, 4 april 2017, di GKS Widyamandala. Diskusi ini dilatarbelakangi antara lain oleh keprihatinan akan kurangnya perhatian kawan-kawan muda Katolik atas perlawanan para petani terhadap pendirian pabrik semen di pegunungan Kendeng, padahal Gereja Katolik memiliki Ensiklik Laudato Si yang dapat menjadi basis gerakan untuk merespons persoalan semacam itu.

Dalam acara tersebut, pemantik diskusi Lilik Krismantoro memulai pembahasan dengan latar sejarah ensiklik. Ada banyak ensiklik yang sudah dikeluarkan gereja. Salah satu ensiklik yang cukup dikenal dan berpengaruh adalah Ensiklik Rerum Novarum yang dikeluarkan oleh Paus Leo XIII. Ensiklik ini merespons perkembangan komunisme di Eropa pada abad ke-18 dan memicu terbentuknya gerakan buruh Katolik. Ensiklik ini membahas dukungan gereja atas hak-hak buruh namun juga mengukuhkan hak milik pribadi dan menolak sosialisme.

Ensiklik Laudato Si merupakan salah satu dari dokumen-dokumen serupa yang lahir kemudian. Ensiklik ini dapat dibaca sebagai lanjutan dari ensiklik serupa sebelumnya, Populorum Progressio, yang dikeluarkan oleh Paus Paulus VI pada 26 Maret 1967 yang hadir sebagai refleksi iman Katolik tentang pembangunan yang berpusat pada manusia. Di luar ensiklik ini, ada praksis-praksis teologis lain yang lahir dari Gereja Katolik, seperti teoologi pembebasan yang menemukan pengejawantahannya dalam perjuangan Uskup Agung San Salvador Mgr Oscar Arnulfo Romero—yang mengalami assasinasi dan belakangan telah ditahbiskan sebagai martir oleh Paus Fransiskus pada 2015.

Terkait persoalan lingkungan, menurut Lilik, Gereja Katolik di Indonesia sebenarnya sudah mulai terlibat aktif sejak lama. Ini tampak misalnya dari keterlibatan Gereja Ganjuran di Yogyakarta sebagai tuan rumah seminar pertanian se-Asia pada tahun 1990 yang diadakan oleh Federasi Konferensi-Konferensi Waligereja Asia (FABC). Dengan bekal beragam gerakan gereja dan ensiklik sebagai pijakan teologisnya, menghubungkan persoalan Kendeng dengan Katolik bukan hal yang sulit. Gereja dan umat Katolik memiliki modal dan alasan yang cukup untuk terlibat aktif dalam persoalan Kendeng.

Menegaskan hal ini, salah seorang peserta diskusi yang juga aktivis pertanian organik, Beni Pudyastanto, mengatakan bahwa secara khusus Ensiklik Laudato Si membahas persoalan air di bab pertama bagian kedua. Dikatakan dalam ensiklik itu bahwa air dapat menjadi sumber konflik. Dalam kasus Kendeng, isu seputar Cekungan Air Tanah (CAT) Watuputih Kendeng adalah salah satu persoalan kunci yang mengemuka dalam polemik kehadiran pabrik semen di Kendeng. Air di CAT akan hilang atau menyusut sebab aktivitas penambangan, yang pada gilirannya merusak suplai air untuk wilayah Rembang, Kudus, Pati, Blora dan sekitarnya.

Beni juga mengingatkan peserta diskusi bahwa Laudato Si mengatakan bahwa keberlanjutan (sustainability) suplai dan ketersediaan air adalah anugerah bagi semua makhluk, dan di level ini manusia dengan makhluk lain berposisi sejarah di hadapan Tuhan. Akal budi yang dimiliki manusia tidak serta merta memberinya hak mutlak untuk mengeksploitasi alam.

Beni juga menegaskan bahwa membicarakan Kendeng dari kaca mata Laudato Si bukan semata-mata berbicara perihal lingkungan, namun juga soal adanya kelompok masyarakat yang butuh dibela di hadapan arogansi kekuasan. Dalam hal ini, ajaran Katolik tentang menolong sesama dan kaum tertindas seharusnya dapat menjadi landasan aksi. Maka, lanjut Beni, Ensiklik Laudato Si ini harus digaungkan sampai ke paroki-paroki hingga akar rumput. Untuk memulai semua itu, menurut Beni, hal pertama harus dilakukan adalah sebagaimana dibahas pada bab enam bagian tiga Ensiklik Laudato Si: pertaubatan ekologis. Setiap penganut Katolik harus bertaubat dari dosa-dosa ekologisnya.

Terkait kelompok miskin tertindas, Lilik menambahkan bahwa saat terjadi ketidakadilan ekonomi dan ekologi, korban terbanyak dan paling utama itu sama: masyarakat miskin. Merekalah kelompok yang paling rentan terdampak bencana akibat rusaknya lingkungan. Lilik mengingatkan peserta bahwa kini telah hadir jenis pengungsi baru, pengungsi lingkungan, yakni pengungsi yang lahir dari kerusakan lingkungan. Menyitir Laudato Si, Lilik mengingatkan bahwa konsep hutang semestinya tak hanya dipahami dalam kerangka finansial, tetapi juga ekologis, yakni hutang negara-negara maju karena mereka mengakses sumber daya alam dan mengorbankan masyarakat miskin dunia ketiga.

Menutup diskusi, Lilik mengajak peserta untuk merenungi iman masing-masing dengan pertanyaan retorisnya: “Harus disadari bahwa hati yang kaugunakan untuk mengasihi itu adalah hati yang sama dengan yang kaugunakan untuk merusak lingkungan. Itu bukan hati yang terpisah. Jadi, bagaimana kita bisa mengasihi jika pada saat yang sama kita merusak alam?!”

Penulis, A.S. Sudjatna, adalah mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2015.

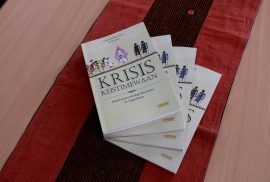

Yogyakarta telah lama menjadi rumah yang aman bagi berbagai tradisi, keyakinan, dan paham pemikiran yang beragam. Tetapi Daerah Istimewa ini belakangan disorot karena banyaknya aksi vigilantisme yang dilakukan sejumlah kelompok massa baik yang berlatar belakang agama atau politik. Aksi-aksi vigilantisme yang menyasar kelompok-kelompok sosial dan keagamaan minoritas menimbulkan pertanyaan apakah Yogyakarta, yang dikenal sebagai kota pendidikan dan pusat kebudayaan Jawa yang menekankan pada harmoni sosial, sudah berubah menjadi daerah yang intoleran? Laporan ini menunjukkan bahwa vigilantisme terhadap minoritas tidak cukup secara sederhana dipahami sebagai ekspresi konservatisme keagamaan dan intoleransi para pelaku terhadap minoritas, tetapi juga merupakan bagian dari proses perubahan sosial dan struktural yang diantaranya dipengaruhi oleh dinamika seputar status keistimewaan Yogyakarta. Tidak bisa dipungkiri, sektarianisme yang menguat belakangan ikut berpengaruh, tetapi seringkali kekerasan terhadap minoritas lebih tampak sebagai alat mobilisasi kelompok-kelompok kepentingan tertentu untuk mempertahankan basis sosial-politik yang menentukan kendali mereka atas ruang dan sumber daya.

_________________________

Judul: Krisis Keistimewaan: Kekerasan terhadap Minoritas di Yogyakarta

Penulis: Mohammad Iqbal Ahnaf & Hairus Salim

Penerbit: CRCS UGM

ISBN: 978-602-72686-7-8

Tebal: 134 halaman; 15×23 cm

Cetakan Pertama: April 2017

Harga: Rp60.000,00

__________________________

Narahubung untuk mendapatkan buku ini:

Divisi Marketing CRCS UGM

Gedung Lengkung Lantai 3

Sekolah Pascasarjana Lintas Disiplin Universitas Gadjah Mada

Jl. Teknika Utara, Pogung, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 55281

Telephone/Fax: 0274-544976

Atau melalui WA: 082141724150 (Bandri)

Lihat juga buku-buku publikasi CRCS yang lain di sini.

Anang G Alfian | CRCS | News

Universitas Gadjah Mada’s Faculty of Biology invited Whitney Bauman to present his on-going project at the Biology Hall on Monday, March 6th, 2017. Students and lecturers from various faculties came to hear his lecture. His specialization on the discourse of religion, science, and nature reflects his capacity as an associate professor at the Department of Religious Studies, Florida International University, as well as author of works including Theology, Creation, and Environmental Ethics (Routledge 2009) and Religion and Ecology: Developing a Planetary Ethics (2014). A longtime friend of CRCS who has taught intersession courses more than once, he is currently working to finish his third, single-authored book with a tentative title Truth, Beauty and Goodness: Ernst Haeckel and Religious Naturalism.

In his lecture, introduced by paleontology lecturer Donan Satria Yudha as the moderator, Bauman engaged religion and science in a contemporary discussion to look for a new way of understanding each through an evolutionary perspective. This perspective of religion-science relationship was inspired by the contemporary phenomenon in which religion has gained more spaces within science.

The emphasis Bauman made in the beginning of the lecture pointed out the direction of his topic of presentation. He started how historically the notion of religion has been discussed by different perspectives from dualism and reductionism to emergence theory. Along with the continuum of religion-science relationship, he challenged to look at the relation in a new way by focusing on the German scientist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) who formulated a new way of making sense out of the world through his studies of ecology and evolution. Bauman clearly stated his stance: “to place Haeckel’s Monism in continuity with this tradition of meaning-making.” He also emphasized that everything has undergone changes and the way we understand the relation between religion and science has always been a “relationship in constant flux.” He challenged the assumption of the previous models on religion-science relationship that views Religion and Science as two different traditions. “I argue that Religion and Science are always together, influencing one another,” Bauman continued, “there is no clear separation.”

As Bauman prefers to define “religion” through its meaning-making function, he observed that the way religion attains knowledge is also inseparable from the natural evolution perspective. Further, he explained that the relation involves not only human and nature as a traditional dichotomy but more as an interconnectedness of everything. This view triggered questions from the audience.

One member of the audience asked a question on a human special status over the rest of nature which challenged the way certain traditions or religions view the status of humans in their scriptures. “I am not sure if humans have a special status in nature,” Bauman answered, “In fact, not only humans have culture and language; many other creatures might have them too.” Because knowledge is always in process and moves together with history and experiences, he argued that it is normal for many traditions to have different understandings of nature and the Truth.

Another question posed was about whether the first human walking on earth was the one as narrated in the scripture. Baumann referred to “Adam” as mentioned in the Genesis as its literal meaning, i.e. a creature on the earth which did not refer to any specific gender. In addition, Donan Satria Yudha said that some Muslim scientists say that Homo sapiens may constitute the first human as mentioned in the scripture and it refers to the quality of being human in the evolution, and not to a specific figure.

The writer, Anang G Alfian, is CRCS student of the 2016 batch

Subandri Simbolon | CRCS | Berita

Agar tak salah arah, kebijakan seharusnya berdasar pada riset. Kesenjangan antara kebijakan dengan pengetahuan acapkali berujung pada kebijakan yang tak menyelesaikan masalah. Termasuk di sini kebijakan yang berkenaan dengan umat beragama.

Untuk menjembatani pemerintah dengan akademisi, pada 14 Februari 2017 Balitbang Kementerian Agama bekerja sama dengan Pusat Studi Agama dan Demokrasi (PUSAD) Paramadina mengadakan diskusi dengan topik mengenai definisi agama dan penodaan agama sebagai rangkaian dari serial diskusi “Analisis Kebijakan: Riset dan Kebijakan Terkait Kehidupan Beragama di Indonesia”. Serial diskusi ini direncanakan akan menghasilkan buku terkait tema-tema seperti intoleransi, konflik agama, kebebasan beragama dan berkeyakinan, dan kerukunan antarumat beragama. Forum diskusi itu dihadiri berbagai kalangan dari pihak Kemenag, termasuk Menteri Agama Lukman H. Saifuddin, para akademisi dan aktivis. Dua dosen Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (CRCS), Dr Samsul Maarif dan Dr Zainal Abidin Bagir, menjadi pembicara dalam forum itu.

Definisi Agama

Samsul Maarif memaparkan ulasannya dengan tajuk “Meninjau Ulang Definisi Agama, Agama Dunia, dan Agama Leluhur”. Ia menyampaikan bahwa definisi agama saat ini cenderung diskriminatif karena menggunakan paradigma “agama dunia” (world religion) untuk menilai agama lokal. Paradigma ini dalam diskursus klasik Barat prototipenya adalah Kristen sedangkan dalam konteks Indonesia adalah Islam. Agama-agama lokal, dalam paradigma ini, cenderung menempati posisi yang lebih rendah. Penggunaan paradigma agama dunia itu bukan saja menyusup ke dalam cara pengambilan kebijakan oleh pemerintah, melainkan juga telah menghantui dunia akademik di Indonesia.

Berdasar pada kritik itu, Samsul menyampaikan bahwa pemahaman mengenai agama yang cenderung esensialis harus dihindari, karena agama mesti dipahami secara diskursif berdasarkan konteks waktu, tempat, dan sejarahnya. Yang sebenarnya lebih diperlukan adalah mempertimbangkan definisi dari segi efektifitasnya dalam memecahkan masalah. Dalam hal ini, definisi yang dibuat seharusnya dapat membebaskan kelompok-kelompok tertentu, utamanya kalangan penganut agama leluhur, dari perlakukan diskriminatif.

Di samping itu, Samsul menegaskan bahwa kebijakan dan studi terhadap para penganut agama leluhur mesti dilakukan dalam konteks keragaman agama, yakni bahwa para penganut agama leluhur mendapat kebebasan untuk mendefenisikan agama mereka sendiri. Pemerintah diharapkan dapat memfasilitiasi self-determinism warganya dan melihat mereka sebagai warga negara yang setara. Definisi yang baik adalah definisi yang mampu memberikan hak-hak yang setara pada semua penganut agama, baik agama-agama dunia maupun agama-agama leluhur dan kepercayaan, di Indonesia.

Kebebasan Beragama dan Berkeyakinan

Dalam forum yang sama, Dr Zainal Abidin Bagir berbicara untuk tema “Kajian tentang Kebebasan Beragama dan Berkeyakinan di Indonesia dan Implikasinya untuk Kebijakan”.

Zainal memaparkan diskusi mutakhir tentang Kebebasan Beragama dan Berkeyakinan (KBB) baik di tingkat internasional maupun nasional serta tema-tema yang menonjol. Ia menegaskan bahwa dalam diskursus di tingkat internasional KBB bukanlah konsep yang sudah fixed dan statis, namun mengalami perkembangan hingga saat ini. Di antara masalah yang masih kerap muncul hingga kini dalam diskusi KBB adalah pertentangan antara mereka yang mengklaim universalitas KBB, sebagai bagian dari Deklarasi Universal Hak Asasi Manusia (DUHAM), dan negara-negara yang menggunakan sudut pandang partikularistik, yang merelatifkan KBB.

Terlepas dari itu, perkembangan yang menarik adalah regionalisasi HAM, yaitu diadopsinya HAM oleh beberapa regional, termasuk Uni Eropa, ASEAN, dan Organisasi Kerja Sama Islam (OKI). Lebih jauh, meskipun ada kecenderungan partikularistik itu, dalam perkembangannya HAM ASEAN dan OKI cenderung mengalami konvergensi ke HAM internasional.

Di Indonesia sendiri, Zainal melihat beberapa perkembangan penting HAM setelah 1998, termasuk ratifikasi beberapa kovenan, dan masuknya klausul khusus mengenai HAM dalam amandemen Undang-Undang Dasar. Selanjutnya, terjadi pengarusutamaan KBB dalam berbagai UU. Perkembangan ini menurut Zainal menjadi sebuah nilai plus bagi Indonesia jika dibandingkan dengan perkembangan regional, khususnya jika dibandingkan dengan banyak negara ASEAN dan OKI. Di Indonesia pun, partikularisasi KBB terjadi, yakni dalam menghadapkan HAM dengan apa yang dianggap sebagai kultur Indonesia dan aspirasi keagamaan sebagian kelompok beragama, khususnya muslim. Salah satu bentuk partikularitas itu diekspresikan dalam konsep “kerukunan”, yang hingga tingkat tertentu menjadi pembatas kebebasan.

Di bagian akhir paparannya, Zainal mengajukan beberapa rekomendasi untuk pengembangan kajian dan perumusan kebijakan terkait KBB. Pertama, “membumikan” KBB dalam tradisi kultural atau keagaman untuk memperluas tingkat penerimaan publik. Kedua, perlunya ada kajian komparatif dengan praktik-praktik kebijakan KBB di negara-negara lain untuk memperkaya perspektif dalam mengidentifikasi faktor-faktor yang menyumbang atau menghambat keberhasilan perumusan maupun implementasi kebijakan. Ketiga, perlunya ada perhatian pada best practices dari praktik-praktik yang sudah terjadi agar kajian kebijakan tak hanya melihat aspek legal secara abstrak namun juga situasi dan kondisi yang memungkinkan keberhasilan perumusan dan penerapan kebijakan.

Batas minimal?

Dalam sesi tanya jawab, Menteri Agama Lukman Hakim Saifuddin mengajukan satu pertanyaan tentang batas minimal yang harus dilakukan negara dalam Perlindungan Umat Beragama (PUB). Andreas Harsono, dari Human Rights Watch, menjawab bahwa batas minimal adalah tidak terjadinya kekerasan kepada kelompok keagamaan manapun. Zainal melanjutkan dengan menyampaikan bahwa hak-hak administrasi kependudukan, kebebasan beribadah harus dipenuhi bagi semua pemeluk agama, terlepas dari bagaimana agama didefinisikan.

Kasus-kasus yang acapkali terjadi adalah sulitnya sebagian kalangan untuk mendapatkan hal-hak konstitusionalnya. Di beberapa daerah, hak-hak dasar pemeluk agama leluhur belum terlayani secara penuh. Misalnya, seorang anak tidak bisa dimasukkan dalam Kartu Keluarga orang tuanya hanya karena perkawinan mereka berdasarkan agama leluhur dan tak dapat dicatat dalam pencatatan sipil. Hal ini para gilirannya berakibat pada hilang atau berkurangnya akses-akses dalam bidang lain seperti pendidikan, kesehatan dan hak politik.

Di akhir diskusi, Menteri Agama menyampaikan bahwa Kementerian Agama terbuka untuk menerima masukan dari semua pihak, khususnya dalam upaya merumuskan RUU Perlindungan Umat Beragama yang sedang diproses.

Abstract:

Urban people are always exposed to soundscape, to sounds and noises in their everyday life. With the aid of technology, the soundscape of Yogyakarta has dramatically changed in the last 30-40 years. The sounds which once gave certain characteristics to the city have changed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For most people it does not bother them if they do not pay attention to them. However, people accept certain sounds as acceptable sounds while some other may reject them as disturbing noises. The result of such perceptions create spsychologically different responses, either positively or negatively. Therefore, exploring how people in the City of Tolerance responding to the religious soundscape of the place where they live is an effort to see an interfaith relationship from a different perspective, the auditory angle.

Speaker:

Jeanny Dhewayani, Ph.D. is the Associate Director of Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS) Yogyakarta.She got her Master degree from University of New Mexico and Ph.D. from Australian National University, both in Anthropology. Now, She is also a professor of anthropology at Duta Wacana Christian University.

Anang G Alfian | CRCS | Event

Issues of environmental damage are becoming more pervasive recently. It was just a few months ago we hear the voices of Samin community, indigenous people in the slopes of Mount Kendheng advocating environmental justice against industrialization attack surrounding the mountain, the issue of which inspired Dian Adi M.R., one of CRCS students, to compose instrumental music and conceptualize arts performance at the event called “Sounds of The Indigenous”.

Through his experience in music performance, Dian initiated the event and collaborated with various musicians, environmental activists, and academia of religious and cultural studies. This innovative way of giving collaborative performance is purposively to raise an awareness among various professions to work together on preserving nature.

Held at Taman Budaya Yogyakarta, many visitors crowded the event on the eve of January 25th 2017 to see the performance, which was started by a documentary film about the semen factory against Samin people and other environmental issues happening recently. Some commentaries from local peoples, scholars, and villagers were narrating a number of environmental problems especially in dealing with actors of interests and exploitation of nature. There is a need of consolidation and urgent answer to avoid further consequence of human misconducts toward nature.

As the introduction to the theme was read, a theatrical performance began to tell narratives and stories, and the instrumental music slowly echoed and filled the air of the room. Visitors seemed to enjoy the mystical yet artistic nuances coming out of the cello playing. Throughout the performance, music and theatrical arts were integrated and made a harmonious blend.

Some instruments were used to represent different and rich sounds from different cultures and origins. Besides guitar, violin, and other common instruments, there were also Gambus, a Middle Eastern music instrument played in the end of the session with Arabic vocal. A Dayak instrument called Sape was also used to sing with a children song. It produced a nostalgic scene of happy life when children can play with nature before industrialization has polluted environment and water.

A theatrical narrative called “Hunger” was also enacted to convey indigenous voices demanding justice and prosperity. The story was meant to see how the man’s greed is always the cause of destruction. “Those local cultures are indeed real guardians of the nature, while ironically many intellectuals go with the interests of those people to build their projects ignoring the locals and the environment,” said Dian commenting on the theme of the performance.

Music can be a means to harmonize the relation between human and nature and awaken the awareness of the shared duty to preserve nature. Justitias Jellita, the Cello player, reflected on music as being in a harmony as she said, “The harmony is not only for musical tunes, but also for the self and the universe. Without harmony, journey of life will lose its meaning, and those who can return to his home is the ones that know where they come from. This Sounds of the Indigenous event is a valuable message and important warning that human will return to his home “Earth” anyway. Therefore, while alive, we’re responsible for our home.”

Music can be a means to harmonize the relation between human and nature and awaken the awareness of the shared duty to preserve nature. Justitias Jellita, the Cello player, reflected on music as being in a harmony as she said, “The harmony is not only for musical tunes, but also for the self and the universe. Without harmony, journey of life will lose its meaning, and those who can return to his home is the ones that know where they come from. This Sounds of the Indigenous event is a valuable message and important warning that human will return to his home “Earth” anyway. Therefore, while alive, we’re responsible for our home.”

Indigenous people of Dayak tribe have their own cosmology on their music as what Anang, the Sape player, said, “For Dayak people, they believe an old saying, ‘Sapeh Benutah tulaang to’awah,’ meaning Sape can crush the bones of evil ghosts.”

This event has given us a lesson on how to maintain the relation between man and nature as important elements in the harmony of life. And music is one of the languages the indigenous speak with. Now it is our turn whoever we might be; artists, scholars, or environmental practitioners; to know where we stand on and where we are going to return.

*Anang G Alfian is CRCS student of the 2016 batch

Abstract

Iranian cinema is one of the very few in the Muslim world to have employed this new medium in imagining and narrating stories of religious figures. The representation of religious figures in Islam has become particularly controversial in recent years. Therefore, it turned into a highly sensitive undertaking. In this talk I examine the complex socio-political context of Iran to study late emergence of the epic genre in Iranian cinema. In doing so I study the recent creation and development of ‘Qur’anic Films’ within Iranian cinema with specific reference to Kingdom of Solomon (Mulk-i Sulayman-i Nabi, Shahriar Bahrani, 2010), which I argue is the first Qur’anic epic in Iranian cinema if not in the Muslim world.

Speaker

Dr Nacim Pak-Shiraz is the Head of Persian Studies and Senior Lecturer in Persian and Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh. She is the author of Shi’i Islam in Iranian Cinema: Religion and Spirituality in Film (London, 2011) and a number of articles and chapters in the field of Iranian Film Studies. Dr. Pak-Shiraz also regularly collaborates with a number of film festivals, including the Edinburgh International Film Festival and The Edinburgh Iranian Festival.

Abstract:

In this discussion, Jonathan Zilberg will discuss problems fracing Indonesian museum in terms of performance, accountability and transparency. He will discuss the Goverment of Indonesia’s 2010-2014 museum revitalization program, the transformations that have been taking place in Indonesia museum over the last decade and the challenges posed for the future. He will look at museums as democracy machines and as postcolonial centers for advacing the ideology of pluralism in civil society. In particular he will address the integrated importance of museums, adchives and libraris for advacing the state of education at all levels including for countinuing adult education.

Speaker:

Jonathan Zilberg is a cultural anthropologist specializing in art and religion and in museum ethnography. He has been studying Indonesian museums for a decade and is particularly interested in museums as democracy machines and as post-colonial centers for advancing the ideology of pluralism in civil society. His immediate interests focus on Hindu-Buddhist heritage including the function of archaeological sites as open air museums as well as of museum collections and government depositories in terms of being under-utilized academic resources. For comparative purposes, he has studied museums in Aceh, Jambi, Jakarta and to a lesser extent observed select museums elsewhere in Indonesia. Currently he is CRCS UGM Visiting Scholar.

Abstract:

The Green Santri Network aims to be a socio-ecological movement by Indonesian Muslim groups, using Muslims’ own sensibility and ‘thought language’ to effectively disseminate messages about Islamic ecological values for survival and sustainability and to advance the idea of relocalization, or returning to a smaller scale, as self-reliant communities with simpler ways of living and with self-local governance. It comes out of my research into how Indonesian Muslim groups, including both the large-scale Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama and two examples of green intentional communities, Hidayatullah and An-Nadzir, can contribute toliving knowledge transmission or murabbias a way to make sustainability education relevant in the Islamic symbolic universe in the Indonesian context,based on the understanding that more than intellectual ability is needed to comprehend this knowledge; it must be made personal by living it.

Speaker:

Wardah Alkitiri earned her Ph.D. in Sociology at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, in 2016. Her dissertation was entitled “Muhammad’s Nation is called “The Potential for Endogenous Relocalisation in Muslim Communities in Indonesia”. She is founder of AMANI, a not-for-profit organization that aims to promote ecological sustainability through entrepreneurial creativity in Jabodetabek and Central Java.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Al Makin, a lecturer from ICRS and Ushuluddin Faculty in UIN Sunan Kalijaga, gave a fascinating presentation about his newest book Challenging Islamic Orthodoxy (Springer, 2016). He began his presentation by commenting that his research on prophethood in Indonesia may not be very new to the ICRS and CRCS community, but discussion of the polemics of prophethood is interesting as Indonesia is home for both the largest Muslim population of any country in the world and to many movements led by self-proclaimed prophets after the Prophet Muhammad. In Al Makin’s perspective, we should see this phenomenon from a different perspective, as part of the creativity of Indonesian Muslim society.

In 1993, the Ministry of Religious Affairs issued a selection of characters of what constitutes religion, include the definition of the prophet, a requirement of recognized religions. According to the Ministry of Religious Affair, prophets are those who receive revelation from God and are acknowledged by the scripture. However, following Islamic teaching, Muhamad is the seal. God no longer directly communicates with humankind. In Al Makin’s definition, prophets are those who, first, have received God’s voice and, second, establish a community and attract followers. He also reported that the Indonesian government has listed 600 banned prophets that fit these criteria. Interestingly, Indonesian prophets tend to come from “modernist” backgrounds connected to Muhammadiyah, which rejects other kinds of traditional and prophetic religious leadership, like wali and kyai.

After two years of trying, Al Makin gained complete trust from one well-known prophet in Jakarta, Lia Eden, and her community of followers. The wife of a university professor, Lia Eden was famous as a flower arranger and close to members of President Suharto’s circle. She quit her career when she was visited by bright light she later identified as Habibul Huda, the archangel Gibril. After that, she became prolific in her prophecies. She found many skills that she had not had before, like healing therapy. Her circle become a movement called Salamullah, meaning “peace from God” but also referring to salam or bay leaves, used in her healing treatment.

In orthodox Islam, there are no women prophets and no prophets after the Prophet himself. The ulama declared her and her followers heretics. Lia Eden returned the criticism, accusing the ulama of being conservative and criticizing Islam as an institution, especially how the ulama council uses its political power and authority.

Al Makin closed his presentation by showing the way public has responded to Lia Eden. This movement can be considered a New Religious Movement sparks controversy because of how they attract followers. In Indonesia it is more about theology than political or economic interest like it is elsewhere. Ultimately, Al Makin argues that Indonesia’s prophets should be recognized as unstoppable—they usually become more active when in prison—but should be seen as part of the wealth of Indonesia pluralism.

Al Makin responded to a question from Mark Woodward about why Lia Eden’s community with only 30 members would become such a big problem for the government by citing Arjun Appadurai, who has argued that a small number becomes a threat to the majority in terms of its purity. It is true that she has a very small number of followers but she is also very bold and outspoken in deliver her messages constantly sending letters to many political leaders, including the ambassadors from other countries and issuing very public condemnations. Greg, another lecturer from CRCS, also asked why she is called bunda and whether she is making a gender-based critique. Al Makin answered that there have been a few other women prophets besides Lia Eden in Indonesia and that Lia Eden’s closest associates are women.

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Class Journal

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

As an American lecturer who has been working with CRCS since 2014 through Eastern Mennonite University, Virginia, he is a very well-experienced educator as he previously spent some years teaching in Japan. Moreover, his interest in following up the up-dated global issues including religious nuances, made him familiar with framing the methods of studying religion and globalization.

Global ethics is one of the topics we discussed in the class, the last material before the end of the class. Previously, we talked a lot about globalization as a phenomenon affecting religions as well as several religious responses toward globalization. Despite the supporters of globalization, many religions seem to fearfully reject it, some even proclaiming their resistance and becoming more radical.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Therefore, to foster the stabilization of the world order from war and disputes, it is necessary to rethink globalization in ways that are more ethical and friendly to the world. On the topic discussion of global ethics, we learned about attempts by world organizations like the United Nations in generating international agreements including the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Besides, other agreements such as the Cairo and Bangkok Declarations represent local voices which to some points define human rights differently.

The difference in worldviews among international actors is interesting because each organization tries to define a global value within their own relativities. Moreover, some theories think that UN Declaration on Human Right is a Western domination over other cultures without considering cultural relativities, including religions, each of which inherits different theological and structures while at the same time sharing common values like peace, humanity, equality, and justice.

World issues indeed became valuable perspective in this class. Students are meant to not only understand theories but also keep updating their knowledge on what is happening in the recent international world. While negative influences of globalization such as war, religious radicalization, and other world disputes were discussed in the class, there is also a hope for a global agreement and bright future by sharing noble values like cooperation, justice, human dignity, and peace on global scale. The existence of world organizations and religious representatives in fostering global ethics proves the progress made towards creating world peace. The duty of students, in this case, is to contribute academically to spreading such values without neglecting the variety of cultural and religious perspectives.

*The writer is CRCS’s student of the 2016 batch.

Anang G. Alfian* | CRCS | Class Journal

Salah satu mata kuliah yang diajarkan di CRCS adalah Religion, Violence, and Peace Building (Agama, Kekerasan, dan Perdamaian). Tiga kata kunci ini menjadi variabel dan titik tolak diskusi tentang hubungan agama dan konflik sosial dan bagaimana upaya untuk membangun perdamaian.

Diampu oleh Dr. Iqbal Ahnaf, mata kuliah ini membahas, antara lain, persoalan relasi antara agama dan konflik. Ini dibahas di pertemuan pertama untuk membuka wawasan tentang perdebatan yang terjadi mengenai hubungan kausalitas antara agama dan kekerasan.

Pada pertemuan ini, satu dari dua bacaan yang dipakai sebagai bahan readings adalah artikel dari Andreas Hasenclever dan Volker Rittberger, Does Religion Make a Difference?: Theoretical Approaches to the Impact of Faith on Political Conflict (Journal of International Studies, 2000).

Dalam artikel itu, Hasenclever dan Rittberger memaparkan tiga mazhab dalam dunia akademik dalam membaca hubungan agama dan konflik, yaitu (1) primordialis, (2) instrumentalis, dan (3) konstruktivis.

Kaum primordialis berpandangan bahwa agama dalam dirinya sendiri memiliki unsur inheren yang dapat menyebabkan konflik. Ketika terjadi “konflik agama”, agama dibaca oleh kaum primordialis sebagai variabel yang independen, unsur yang tidak bergantung pada aspek-aspek lain, dan perbedaan identitas keagamaan itu sendiri bisa cukup sebagai penyebab konflik.

Kaum instrumentalis melihat peran agama dalam “konflik agama” sebagai instrumen saja, dan tidak memiliki peran objektif dalam dirinya sendiri. Menurut kaum instrumentalis, penyebab utama konflik adalah kepentingan politik dan ekonomi. Bagi kaum instrumentalis, agama hanya berperan dalam retorika saja, dan relasinya dengan konflik bersifat semu belaka.

Kaum konstruktivis tampak berada di tengah-tengah antara kedua kelompok di atas. Konstruktivis bersetuju dengan instrumentalis dalam hal bahwa penyebab fundamental konflik bukanlah agama, melainkan kepentingan politik dan ekonomi. Namun konstruktivis juga bersepakat dengan primordialis dalam hal bahwa agama memiliki peran nyata objektif, namun bukan sebagai penyebab utama, melainkan eskalator konflik. Agama, ketika terlibat dalam konflik, dapat membuat konflik semakin mematikan, deadly. Juga, berbeda dari primordialis yang berpandangan bahwa agama menjadi variabel independen dalam konflik, bagi kaum konstruktivis agama berperan secara dependen, tergantung pada faktor-faktor ekonomi dan politik lain yang melingkupi konflik tersebut; seberapa besar peran agama mengeskalasi konflik tergantung pada seberapa akut benturan antar kepentingan politik dan ekonomi dalam konflik itu.

Ketiga cara pandang di atas tidak bisa diperlakukan secara universal. Tapi ketiganya bisa dijadikan lensa analitis dan ditempatkan dalam suatu spektrum. Bagaimana menentukan peran agama dalam suatu konflik mestilah dimulai dari detil kasus konfliknya, lalu naik melihat lensa-lensa analitis yang ada, kemudian menentukan di antara yang tersedia manakah penjelasan yang lebih tepat.

Dalam “kasus Sunni-Syiah” Sampang, misalnya, dimensi konflik yang terjadi bukan hanya karena faktor perbedaan ideologis semata, namun juga karena adanya instrumentalisasi agama oleh elite politik, karena konflik ternyata bereskalasi pada masa perebutan kekuasaan menjelang pemilu daerah, sehingga narasi-narasi agama di legitimasi sedemikian rupa untuk suatu tujuan politik. Dalam melihat hal ini, kita tak bisa berhenti pada pandangan kaum primordialis—inilah pandangan yang diadopsi oleh mereka yang memercayai bahwa konflik Sampang itu adalah konflik Sunni-Syiah. Dimensi sosial politik dalam konflik itu wajib dihitung, mulai dari yang kecil seperti persengkataan internal keluarga, perebutan umat, hingga yang lebih makro seperti instrumentalisasi konflik untuk mendulang dukungan dalam pemilu.

Dalam perspektif konstruktivis, intervensi terhadap konflik dengan menyuarakan nilai-nilai kebajikan agama, kearifan lokal, dan slogan-slogan orang Madura Sampang sangat membantu upaya rekonsiliasi konflik, yakni untuk melakukan deskalasi terhadap konflik itu dengan mengajukan narasi tandingan primordialis. Penelitian Dr. Iqbal Ahnaf beserta peneliti yang lain dalam serial laporan CRCS tentang kehidupan beragama di Indonesia yang bertajuk Politik Lokal dan Konflik Keagamaan menunjukkan instrumentalisasi agama oleh elit politik di Sampang menjelang pilkada. Tesis S2 terkait kasus Sampang ini juga ditulis oleh mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2010 Muhammad Afdillah yang kini telah dijadikan buku dengan judul Dari Masjid ke Panggung Politik.

Kasus Sampang merupakan contoh yang bagus untuk membaca seberapa besar peran agama dalam konflik, dan ini membutuhkan data dan analisis yang cermat. Contoh-contoh lain dari yang terjadi di Indonesia yang bisa diambil ialah kasus Ambon dan Poso, atau yang belum lama ini terjadi seperti di Tolikara, Tanjungbalai, atau bahkan kasus dugaan “penodaan agama” dalam pilkada Jakarta.

*Penulis adalah mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2016

Ilham Almujaddidy & A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Event Report

Dialog antaragama sebagai upaya penyelesaian konflik bukan hal yang mudah dilakukan. Tidak jarang terjadi, dialog yang dimaksudkan untuk menjembatani perbedaan dan meminimalisasi konflik tidak berjalan sesuai tujuan awal, atau bahkan kontraproduktif dan menimbulkan masalah baru.

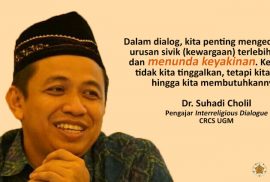

Dalam diskusi Forum Umar Kayam, Pusat Kebudayaan Koesnadi Hardjosoemantri (PKKH) UGM, pada Senin 25 Juli 2016, dosen CRCS Dr. Suhadi Cholil membahas persoalan ini. Dalam diskusi bertajuk “Menunda Keyakinan: Refleksi Membangun Pluralisme dari Bawah” itu, pengajar matakuliah Interreligious Dialogue di CRCS ini memberikan identifikasi-identifikasi penyebab dialog gagal mencapai tujuannya.

Pertama, kurangnya pemahaman substantif tentang fungsi dan metode dialog antaragama yang menyaratkan, antara lain, adanya saling percaya. Adanya praduga-praduga negatif terhadap mitra dialog dapat menimbulkan tiadanya saling percaya itu, dan pada gilirannya menjadi hambatan utama bagi efektivitas proses dialog.

Kedua, dialog antaragama yang semestinya menjadi interaksi untuk saling mengakomodasi masing-masing pihak yang terlibat, dalam prosesnya, malah terjebak dalam upaya untuk mendominasi.

Ketiga, dialog antaragama diandaikan sebagai penuntas konflik. Yang jarang dipahami, dialog dalam praksisnya tidak serta merta bisa menyelesaikan konflik. Beberapa konflik, apalagi konflik agama yang melibatkan klaim-klaim teologis yang sulit untuk dijembatani, tidak mudah dimediasi dengan dialog semata, dan karena itu memerlukan alternatif resolusi konflik yang lain.

Dengan menyadari hal-hal yang menghambat dialog antaragama itu, pemahaman yang tepat mengenai fungsi dan metode dialog antaragama bagi para pihak yang terlibat di dalamnya mutlak diperlukan, termasuk mensinergikan pengetahuan teoretis dan praksis.

Yang kerap menjadi problem di lapangan ialah banyak akademisi yang hanya fokus pada persoalan-persoalan teoretis atau teologis semata, namun abai pada ranah praktis. Sementara di sisi lain, ada banyak aktivis yang kurang reflektif secara teoretis maupun teologis, namun begitu aktif di pelbagai aktivitas dan advokasi perdamaian. Ketika kedua belah pihak ini terlibat dalam sebuah dialog, kerap kali muncul kesalahpahaman yang dapat memicu timbulnya permasalahan baru, dan karena itu kontraproduktif.

Hal lain untuk meminimalisasi hambatan dalam dialog antaragama ialah dengan mendudukkan isu teologis secara tepat. Tidak dapat dimungkiri, isu teologis merupakan isu sensitif, dan karena itu, jika tak hati-hati, justru dapat merusak proses dialog itu sendiri. Dalam proses dialog antaragama, isu teologis berada dalam ketegangan antara klaim eksklusifitas dan kehendak untuk menerima adanya keyakinan yang berbeda.

Dalam persoalan yang terakhir ini, Dr. Suhadi tidak mengusulkan untuk membuang eksklusivitas itu. Baginya, eksklusivitas itu sendiri tidak salah dalam dirinya sendiri. Ia akan menjadi masalah ketika tidak diterjemahkan dengan proporsi yang tepat di ruang publik. Banyak dari yang terlibat dalam proses dialog tidak membedakan antara ruang privat untuk ranah teologis dan ruang publik untuk pencarian titik temu guna menyelesaikan konflik. Karena kurangnya pemahaman untuk melokalisir klaim-klaim teologis pada ranah pikiran dan hati, dialog antaragama, alih-alih menjembatani perbedaan, justru rawan menjadi adu klaim teologis.

Merespons isu eksklusivitas teologis dalam dialog antaragama ini, Dr. Suhadi menawarkan gagasan bahwa untuk mengembangkan dialog antaragama yang lebih produktif, perspektif yang terbaik adalah dengan mendahulukan urusan sivik (kewargaan) dan menunda keyakinan. Hal ini tentu tidak berarti keyakinan ditinggalkan. Keyakinan ditunda, tidak dikedepankan, dan baru ditengok kembali ketika dibutuhkan dalam proses dialog.

*Laporan ini ditulis oleh mahasiswa CRCS, dan disunting oleh pengelola website.

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Article

“Jesus as an infant fled with his family into exile. During his public life, he went about doing good and healing the sick, with nowhere to lay his head”.

We were finally in the next to last meeting of Religion and Globalization class. Having studied religion and globalization through the whole sessions, we have come to understand a lot about what role of religions play in accord to globalization and how globalization affects the way religions are concerned with humanitarian issues.

On Monday, November 21, 2016, we had a field trip to one faith-based-NGO to understand how such religious organization works for humanity. Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is one of the well-known international organizations and it was a good place to learn the working field of faith-based organizations. Together with Gregory Vanderbilt as the lecturer of the class, we visited the national office of JRS in Yogyakarta and had a great time meeting Fr. Maswan, S.J., and learning directly from a member of the community

Our visit began with Fr. Maswan’s presentation about the organization. Firstly established in Indonesia in 1999, Jesuit Refugees Services has been accompanying, advocating, and giving services to forcibly displaced people. Therefore, this organization has actually been well experienced in dealing with the issues. As we listen to his presentation, we come to realize that this problem of refugees and asylum seekers cannot be ignored for it belongs to international concern. The perpetuation of war, disasters, racial conflict, and many other causes make refugees seek for their safety life by migrating to other national boundaries.

Our visit began with Fr. Maswan’s presentation about the organization. Firstly established in Indonesia in 1999, Jesuit Refugees Services has been accompanying, advocating, and giving services to forcibly displaced people. Therefore, this organization has actually been well experienced in dealing with the issues. As we listen to his presentation, we come to realize that this problem of refugees and asylum seekers cannot be ignored for it belongs to international concern. The perpetuation of war, disasters, racial conflict, and many other causes make refugees seek for their safety life by migrating to other national boundaries.

However, it has never been easy for refugees because they have to face the legal and often difficult administrative regulations of the government where they are staying. This is exactly what happens to refugees in Indonesia. Because Indonesia has not ratified the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, refugees in Indonesia are not recognized as such by the Indonesian government—instead they are considered undocumented aliens—while they wait for recognition from the UNHCR which will allow them to resettle in another country. In some districts, refugees have to stay in detention center while waiting for their legal refugee status to be acknowledged by the law.

As recorded in JRS monitoring, refugees in Indonesia have reached a number of 4.344 people of whom 540 are female and 905 are children with 96 being unaccompanied minors and seperated children. So far, JRS has been accompanying two detention centers in Surabaya and Manado and being involved in other areas as well. In Aceh, JRS has advocated for protection over 625 people and has given psychosocial accompaniement to over 1558 refugees. In Yogyakarta, they are serving the refugees, mostly from Afghanistan, housed in the Ashrama Haji. They listen, accompany, and make activities to give hope for those people who had been separated from their family and their mother land.

So, where is exactly the religion to deal with this? This question come out of students trying to figure out the role of religion in this humanity organization. Then, the community member continued the presentation stating that the mission of JRS is intimately connected with the mission of Society of Jesus to serve faith and promote the justice of God’s kingdom in dialogues with cultures and religions. Yet, another student comes up with another concern, “Does it mean that JSR proselytize Christianity?” Well. This is very important because in the previous meeting, we read through Philip Fountain’s “Proselytizing Development” and he himself attended our class for discussing this topic. In sort, the religion has been inspired by the development organization as precedent in history while, vice versa, religion brings universal ethics to be put in dialogue with cultures and religion.

In the last session of our discussion in JRS offices, Fr. Maswan emphasized some points such as it is the problem of humanity that we have to be concerned about and not at all concerned in religious kind of missionary work altough it might inspired the organization in its underlying ethics, building cooperation with other cultural, faith-based, and other types of organization. We also read the paper Fredy Torang (2013 batch) presented in Singapore about how JRS acts as an agent of “humanitarian diplomacy” between the refugees and the local communities and government. In 2017, JRS will continue lobbying local government to allow refugees to live in a community and not in detention and also monitoring the migration all over the world to help assisting the displaced people and consistently gives concern to human right and dignity.

In the last session of our discussion in JRS offices, Fr. Maswan emphasized some points such as it is the problem of humanity that we have to be concerned about and not at all concerned in religious kind of missionary work altough it might inspired the organization in its underlying ethics, building cooperation with other cultural, faith-based, and other types of organization. We also read the paper Fredy Torang (2013 batch) presented in Singapore about how JRS acts as an agent of “humanitarian diplomacy” between the refugees and the local communities and government. In 2017, JRS will continue lobbying local government to allow refugees to live in a community and not in detention and also monitoring the migration all over the world to help assisting the displaced people and consistently gives concern to human right and dignity.

Komunitas tangguh adalah prasyarat utama bagi pembangunan sosial ekonomi yang berkeadilan. Bangunan komunitas tangguh selalu dilandasi dengan pondasi modal sosial yang kuat. Indonesia, termasuk Papua diketahui memiliki ragam modal sosial atau sering disebut dengan kearifan lokal yang diwariskan leluhur. Modal sosial/kearifan tersebut tidak hanya menguatkan ikatan komunitas, tetapi juga antar komunitas. Hanya saja, modal sosial warisan leluhur sering dianggap sudah kurang efektif karena kuatnya tantangan globalisasi. Di tengah kompleksitas fenomena globalisasi, modal sosial/kearifan lokal kembali dilirik dan dipercayai memiliki potensi dan efektivitas untuk kembali membangun komunitas yang tangguh. Ia bahkan dipercayai sebagai cara utama untuk menjamin pembangunan sosial, budaya, ekonomi yang berkeadilan: pembangunan berbasis komunitas.

Pelatihan ini bertujuan untuk memperkuat jejaring kader/fasilitator dalam membangun komunitas tangguh dengan merevitalisasi atau mereproduksi modal-modal sosial/kearifan lokal “hidup bersama” melalui program-program pengembangan komunitas di Papua, khususnya Jayapura dan Merauke.

Pelatihan ini diselenggarakan oleh Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (CRCS) UGM, Yogyakarta bekerjasama dengan Ilalang Institut, Jayapura. Pelatihan akan berlangsung selama 5 hari, pada:

Tanggal : 20 – 24 Februari 2017

Tempat : Kota Jayapura

Persyaratan:

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

“Like the study of feminism, masculinity can be an important approach in religious studies. The study of masculinity emphasizes how man superiority has been graded or perceived from time to time that in turn it becomes a norm for society.”