Abstract:

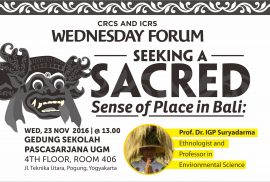

Every tradition in the world employs symbolism, but symbolism reaches acme in Hinduism. However, modern communities seem to be missing the meaning of symbolism. Most of Indonesian ethnicities, especially the Balinese, hold certain views about reality of the world, including the interconnection between the reality of the world and metaphysical world, setting aside days and ceremonies to honor plants, animals, and even inanimate objects have extrinsic and intrinsic value of sacredness. Balinese Hindus are very practical in their religion, striving for the realization of God in daily life, creating oneness and unity with all life on our physical plane and seeking to become sources of light and ambasador of peace.

Speaker:

Prof. Dr. I Gusti Putu Suryadarma is an ethnologist and professor in environmental sciences. He earned his PhD at Bogor Agricultural University on Natural Resources Management. Currently he teaches at Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Science, Yogyakarta State University.

Berita

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

In a world so full of complexity, how does intimacy work? To Dian Arymami, it is very significant and important to revisit the understanding of intimacy because she observes the transformation of intimacy is connected to the transformation of society. The practice, the understanding of intimacy have been reconstructed from time to time. Usually people would think about intimacy as an act of loving, but up to now there are many cases show that intimacy could be something out of love, outside of committed relationship and, to be more precise, outside of marriage. Moreover personal needs and desires are also part of our religiosity. Religiosity and intimacy are not totally opposed to each other.

Dian Arymami’s ongoing research on new kinds of intimacy in the phenomenon of extradyadic or non-monogamous relationships that have quickly become widespread in urban areas of Indonesia is not advocacy on behalf of a group of people but she insists that she is studying the voices of the voiceless. Their emergence can be seen on a practical level as a rebellion against the structure and social fabric of Indonesian society but at the same time as part of an ongoing shift of ideological values and norms. Those who practice extradyadic relationships are a voice that could not be heard by the society because people would always claim that the problem is in person not society. We must think about this kind of intimacy as a social phenomenon and not a personal disease or failing.

Therefore, Dian came up with the signs of embodied practice of intimacy in the schizophrenic society. It related to something that material not representation. It is social not familial and she continue by saying that it multiplicity not personal. Many things transform relationships. According to the cases that Dian come up with, the social media is one of the biggest influence in transforming relationship in society. The discourse about intimacy embodied in the way people perceive things like divorce, sexuality, dating style, poly-amor trend and many others to follow. To define schizophrenic society, she refers to the theory of Gilles Delueze and Felix Guattari about the process of schizophrenia. Unlike Freud’s understanding about paranoia, the schizophrenic term in Delueze shows a condition of an experienced of being isolated, disconnected which fail to link up with a coherent sequence. She than continues that no one is born schizophrenic. Instead, schizophrenia is a process of being. In the schizophrenic society, everyone experiences diverse meanings in relation to other objects, and, in the other times or places, no meaning at all. In other words, meanings are based on the schizophrenic’s object experiences, but it is society itself that must be understood as schizophrenic.

By highlighting her respondents’ experiences, Dian shows that there are many consequences of the practice of intimacy or intimate relationships in (as) the schizophrenic society including “value crash,” double life, “time and place crash” and many others. In extradyadic relationship people become a substitution for something that they cannot fill.

In the question and answer session, there were many fascinating questions about this topic. Zoyer, a researcher concerned with on-line dating in Yogyakarta, offered the idea that the complexity of intimate relationships in urban areas in Indonesia is affected by the cultural expectation that young people marry by certain ages. That is why people are trying to free themselves by “jumping into the extraordinary.” The other question brings us to a reflection about what are the practitioners of these extradyadic relationships are becoming in society. Dian answered by changing the question: instead of questioning a person’s behavior, we must question society. Dian closed her remarkable presentation by stating that the idea of love is not exclusive and absolute.

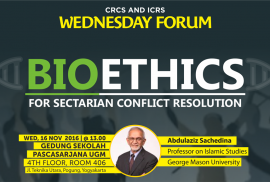

Abstract

Although secular bioethics avoids any entanglement with religious issues, bioethics has the goal of advancing the relationship between the physician, the patient and the patient’s family in medical practice and research, even in tense moments of disagreements in the clinical situation. My involvement in Islamic bioethics, which asserts principles like asserting that bio-ethical principles like “No harm, no harassment” and maslaha or public interest, makes me confident in asserting that two universal principles, which are already operative in the healthcare institutions around the world, can establish peaceful coexistence between members of various communities. These are the value that demands acknowledgment of human equality based in inherent human dignity and the value that teaches humans to relate to one another in sincerity, sensitivity, and a deep sense of sacrifice. I argue they must be applied across all levels of interpersonal relations and interactions.

Speaker

Abdulaziz Sachedina, Ph.D., is Professor and IIIT Chair in Islamic Studies at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. Dr. Sachedina, who has studied in India, Iraq, Iran, and Canada, obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. He has been conducting research and writing in the field of Islamic Law, Ethics, and Theology (Sunni and Shiite) for more than two decades. In the last ten years he has concentrated on social and political ethics, including Interfaith and Intra-faith Relations, Islamic Biomedical Ethics and Islam and Human Rights.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Quoting the great French novelist Victor Hugo’s remark that “Life is a compilation of stories written by God” Inandiak highlighted how meaning is found in stories which come before larger systems like religion. In her book and her talk, she told stories from her experiences with the victims of natural disasters in two communities, one, Kinahrejo, in the North and one, Bebekan,in the South. Inandiak explained that the process of recovery after a natural disaster is a process with and within the nature. It is about the reconciliation between human communities and nature. In natural disasters people mostly lose their belongings such houses, money, clothes and domesticated animals, but, she said, the most important thing is not to lose their identity. Houses can be rebuilt, but once people lose identity they don’t know how to rebuild anything else. Inandiak spoke about the disaster as a conversation between the North and the South. This is also a kind of stories that helps people deal with their situation, by accepting that disaster are part of natural cycles.

Inandiak also spoke about rituals. First there were the rituals enacted by Mbah Maridjan and Ibu Pojo, the shamaness who was his unacknowledged partner, to connect human communities and nature. The offering ritual they made to Merapi included three important layers that describes their own identities: ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam especially Sufism. Despite all the issues that Mbah Marijan and Ibu Pojo faced before they died in the 2010 eruption, they insisted what they were doing is an act of communicating with the nature that was their home. Second, in order to overcome the difficulties after a disaster, stories and ritual mean a lot for reestablishing the victims’ identity. By doing rituals like dancing or singing, they connect to the wishes that become true. The wishes that they made bring such a different in their perspectives in continuing life. Through ritual people want to get connected with nature and Inandiak told how she helped these villages rebuild their identities.

In the question and answer session, we were moved by many fascinating question about the relation of nature and person. One of them is how the three layers in Javanese ritual—reverence for ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam, particularly Sufism—deal with the interference of world religion. Inandiak responded that there must be many changes brings by the world religion, especially in Kinahrejo, where Mbah Maridjan faced pressure from fundamentalists. The way villagers perceive myth changes from time to time. Their Muslim-Javanese identity is something they need to maintain in negotiation. In answering the issues about participants in the rituals wearing hijab, Inandiak argued that these layers should be clearer. They are not rooted in one story. But to maintain the customs is also important.

Inandiak closed her presentation with a remarkable message that disasters come from the interaction of people and nature but no one should feel guilty or think that any disaster is the result of sin or human mistakes. The most important things are not to give up and to work to rebuild identity.

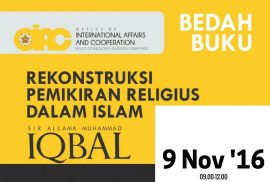

Dinamisme Pemikiran Sir Allama Muhammad Iqbal

Sir Allama Muhammad Iqbal adalah salah satu pemikir Islam papan atas abad 20. Rekontruksi adalah buku filsafat Iqbal yang paling penting. Dia memaparkan serangkaian refleksi mendalam tentang persinggungan antara sains, agama dan filsafat. Iqbal menjadi jembatan timur dan barat, antara Islam dan agama-agama lain. Antara tradisi dan modernitas, wahyu dan akal, spiritualitas dan intelektualitas. Antar seni, ilmu pengetahuan, dan agama.

Penerbit : Mizan 2016

Tempat : Auditorium Fakultas Filsafat UGM, Gedung C lantai 3

Waktu : Rabu, 9 November 2016, Jam 09.00-12.00 wib,

Pembicara : Dr Haidar Bagir, Dr. Mukhtasar Syamsudin, Ammar Fauzi Ph.D

Panitia : Riset STFI Sadra dan Fakultas Filsafat UGM

Abstract

The Islamic Otaku Community (IOC) is an Islamic fan-based community, which encourages young Muslims—male and female—who are actively engaged in otaku fandom to stay committed to Islamic norms and values. Hijab Cosplay can be perceived as a unique site which brings together two worlds, the sacred/ascetic activities of being a Muslimah and the secular/hedonistic activities of the otaku, in which young Muslimah not only choose, appropriate and reproduce characters from Japanese anime, manga and games, but also (re)claim their femininity as Muslimah in relation to it. In this talk, I aim to discuss how Muslim femininity is remediated through the practice of hijab cosplay, which is posted and circulated on the IOC fansite, and how the female dressed body as a mediation of femininity is actively mediated in another medium. Since the goal of remediation is to refashion or reform the earlier version of the medium, I consider the ways in which young Muslimah attempt to refashion and reclaim Muslim femininity through fandom practices. Since cosplay is not confined to the act of costuming, but is also immersed in wider fan practices, I also look at the remediation of Muslim femininity in Islamic Mangaka (fan arts and fans writing produced and posted by IOC members).