Sebanyak 16 peserta, yakni 8 orang dari Jayapura dan 8 orang dari Merauke, mengikuti pelatihan yang diadakan CRCS dan Ilalang Institute.

News

Abstract

Until 1935, the Dutch Protestant mission (zending) in Indonesia was officially run by male missionaries. Women were considered to be supplementary rather than essential actors. Despite the fact that there is only limited information available about them, women were involved in the Dutch Protestant mission from the early nineteenth century. This talk presents a study about the experience and role of Dutch women in the Protestant mission, with particular reference to the existing letters written between 1855 and 1931 by four missionary wives who lived in Sulawesi and North Sumatra. The letters of the four women reveal their domestic and social activities, as well as their perceptions of their role in the mission and the society in which they lived. This talk explores gendered notions in missionary practices and points out the lack of attention to the study of women in Christian missions within the broader framework of Indonesian colonial history.

Speaker

Maria Ingrid Nabubhoga is now a Ph.D. candidate at the Faculty of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies at Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands, in the project ‘Indonesia Mirrors’, jointly organized by Radboud University Nijmegen, The Nijmegen Institute for Mission Studies Radboud University and Duta Wacana Christian University (UKDW). Her Ph.D. project explores the perception of contemporary Indonesian immigrants on religion and modernity in the Netherlands, in continuity with the Dutch colonial past in Indonesia.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | WedForum Report

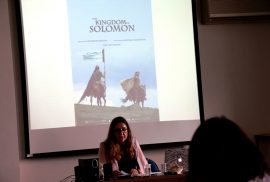

Going to the cinema is a new social practice in modern society. To some extent it can also be perceived as a spiritual practice. Dr Nacim Pak-Shiraz, the Head of Persian Studies and a Senior Lecturer in Persian and Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh and guest speaker at the Wednesday Forum on February 9th, studies this paradox in the dynamics of Iranian cinema. She began by noting that there has been only a little academic attention to the movies based on Quranic epics, in contrast to what has happened with Biblical epics from Hollywood.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | WedForum Report

Jonathan Zilberg, a cultural anthropologist whose research and advocacy focuses on museum ethnography, argued that Indonesian museums face such problems as performance, transparency and accountability, but they have the potential power to promote pluralism to the public. In his February 1st Wednesday forum presentation, he raised questions as to how Indonesian museums can be a strong bond to serve Indonesia’s diversity.

Based on his research in National Museum of Indonesia in Central Jakarta, Zilberg argued that museums are an extension of culture and identity. He conducted his research by closely examining the activities of visitors of National Museum. He took photos from different angles and then reflected on how visitors interact with the objects on display. He stressed that a museum that functions well should be a place to learn and display democracy. Different people come to the museum with various interests. These differences can lead them to learn about pluralism in comfortable ways.

Abstract:

Urban people are always exposed to soundscape, to sounds and noises in their everyday life. With the aid of technology, the soundscape of Yogyakarta has dramatically changed in the last 30-40 years. The sounds which once gave certain characteristics to the city have changed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For most people it does not bother them if they do not pay attention to them. However, people accept certain sounds as acceptable sounds while some other may reject them as disturbing noises. The result of such perceptions create spsychologically different responses, either positively or negatively. Therefore, exploring how people in the City of Tolerance responding to the religious soundscape of the place where they live is an effort to see an interfaith relationship from a different perspective, the auditory angle.

Speaker:

Jeanny Dhewayani, Ph.D. is the Associate Director of Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS) Yogyakarta.She got her Master degree from University of New Mexico and Ph.D. from Australian National University, both in Anthropology. Now, She is also a professor of anthropology at Duta Wacana Christian University.

Anang G Alfian | CRCS | Event

Issues of environmental damage are becoming more pervasive recently. It was just a few months ago we hear the voices of Samin community, indigenous people in the slopes of Mount Kendheng advocating environmental justice against industrialization attack surrounding the mountain, the issue of which inspired Dian Adi M.R., one of CRCS students, to compose instrumental music and conceptualize arts performance at the event called “Sounds of The Indigenous”.

Through his experience in music performance, Dian initiated the event and collaborated with various musicians, environmental activists, and academia of religious and cultural studies. This innovative way of giving collaborative performance is purposively to raise an awareness among various professions to work together on preserving nature.

Held at Taman Budaya Yogyakarta, many visitors crowded the event on the eve of January 25th 2017 to see the performance, which was started by a documentary film about the semen factory against Samin people and other environmental issues happening recently. Some commentaries from local peoples, scholars, and villagers were narrating a number of environmental problems especially in dealing with actors of interests and exploitation of nature. There is a need of consolidation and urgent answer to avoid further consequence of human misconducts toward nature.

As the introduction to the theme was read, a theatrical performance began to tell narratives and stories, and the instrumental music slowly echoed and filled the air of the room. Visitors seemed to enjoy the mystical yet artistic nuances coming out of the cello playing. Throughout the performance, music and theatrical arts were integrated and made a harmonious blend.

Some instruments were used to represent different and rich sounds from different cultures and origins. Besides guitar, violin, and other common instruments, there were also Gambus, a Middle Eastern music instrument played in the end of the session with Arabic vocal. A Dayak instrument called Sape was also used to sing with a children song. It produced a nostalgic scene of happy life when children can play with nature before industrialization has polluted environment and water.

A theatrical narrative called “Hunger” was also enacted to convey indigenous voices demanding justice and prosperity. The story was meant to see how the man’s greed is always the cause of destruction. “Those local cultures are indeed real guardians of the nature, while ironically many intellectuals go with the interests of those people to build their projects ignoring the locals and the environment,” said Dian commenting on the theme of the performance.

Music can be a means to harmonize the relation between human and nature and awaken the awareness of the shared duty to preserve nature. Justitias Jellita, the Cello player, reflected on music as being in a harmony as she said, “The harmony is not only for musical tunes, but also for the self and the universe. Without harmony, journey of life will lose its meaning, and those who can return to his home is the ones that know where they come from. This Sounds of the Indigenous event is a valuable message and important warning that human will return to his home “Earth” anyway. Therefore, while alive, we’re responsible for our home.”

Music can be a means to harmonize the relation between human and nature and awaken the awareness of the shared duty to preserve nature. Justitias Jellita, the Cello player, reflected on music as being in a harmony as she said, “The harmony is not only for musical tunes, but also for the self and the universe. Without harmony, journey of life will lose its meaning, and those who can return to his home is the ones that know where they come from. This Sounds of the Indigenous event is a valuable message and important warning that human will return to his home “Earth” anyway. Therefore, while alive, we’re responsible for our home.”

Indigenous people of Dayak tribe have their own cosmology on their music as what Anang, the Sape player, said, “For Dayak people, they believe an old saying, ‘Sapeh Benutah tulaang to’awah,’ meaning Sape can crush the bones of evil ghosts.”

This event has given us a lesson on how to maintain the relation between man and nature as important elements in the harmony of life. And music is one of the languages the indigenous speak with. Now it is our turn whoever we might be; artists, scholars, or environmental practitioners; to know where we stand on and where we are going to return.

*Anang G Alfian is CRCS student of the 2016 batch