Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Al Makin, a lecturer from ICRS and Ushuluddin Faculty in UIN Sunan Kalijaga, gave a fascinating presentation about his newest book Challenging Islamic Orthodoxy (Springer, 2016). He began his presentation by commenting that his research on prophethood in Indonesia may not be very new to the ICRS and CRCS community, but discussion of the polemics of prophethood is interesting as Indonesia is home for both the largest Muslim population of any country in the world and to many movements led by self-proclaimed prophets after the Prophet Muhammad. In Al Makin’s perspective, we should see this phenomenon from a different perspective, as part of the creativity of Indonesian Muslim society.

In 1993, the Ministry of Religious Affairs issued a selection of characters of what constitutes religion, include the definition of the prophet, a requirement of recognized religions. According to the Ministry of Religious Affair, prophets are those who receive revelation from God and are acknowledged by the scripture. However, following Islamic teaching, Muhamad is the seal. God no longer directly communicates with humankind. In Al Makin’s definition, prophets are those who, first, have received God’s voice and, second, establish a community and attract followers. He also reported that the Indonesian government has listed 600 banned prophets that fit these criteria. Interestingly, Indonesian prophets tend to come from “modernist” backgrounds connected to Muhammadiyah, which rejects other kinds of traditional and prophetic religious leadership, like wali and kyai.

After two years of trying, Al Makin gained complete trust from one well-known prophet in Jakarta, Lia Eden, and her community of followers. The wife of a university professor, Lia Eden was famous as a flower arranger and close to members of President Suharto’s circle. She quit her career when she was visited by bright light she later identified as Habibul Huda, the archangel Gibril. After that, she became prolific in her prophecies. She found many skills that she had not had before, like healing therapy. Her circle become a movement called Salamullah, meaning “peace from God” but also referring to salam or bay leaves, used in her healing treatment.

In orthodox Islam, there are no women prophets and no prophets after the Prophet himself. The ulama declared her and her followers heretics. Lia Eden returned the criticism, accusing the ulama of being conservative and criticizing Islam as an institution, especially how the ulama council uses its political power and authority.

Al Makin closed his presentation by showing the way public has responded to Lia Eden. This movement can be considered a New Religious Movement sparks controversy because of how they attract followers. In Indonesia it is more about theology than political or economic interest like it is elsewhere. Ultimately, Al Makin argues that Indonesia’s prophets should be recognized as unstoppable—they usually become more active when in prison—but should be seen as part of the wealth of Indonesia pluralism.

Al Makin responded to a question from Mark Woodward about why Lia Eden’s community with only 30 members would become such a big problem for the government by citing Arjun Appadurai, who has argued that a small number becomes a threat to the majority in terms of its purity. It is true that she has a very small number of followers but she is also very bold and outspoken in deliver her messages constantly sending letters to many political leaders, including the ambassadors from other countries and issuing very public condemnations. Greg, another lecturer from CRCS, also asked why she is called bunda and whether she is making a gender-based critique. Al Makin answered that there have been a few other women prophets besides Lia Eden in Indonesia and that Lia Eden’s closest associates are women.

News

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Class Journal

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

As an American lecturer who has been working with CRCS since 2014 through Eastern Mennonite University, Virginia, he is a very well-experienced educator as he previously spent some years teaching in Japan. Moreover, his interest in following up the up-dated global issues including religious nuances, made him familiar with framing the methods of studying religion and globalization.

Global ethics is one of the topics we discussed in the class, the last material before the end of the class. Previously, we talked a lot about globalization as a phenomenon affecting religions as well as several religious responses toward globalization. Despite the supporters of globalization, many religions seem to fearfully reject it, some even proclaiming their resistance and becoming more radical.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Therefore, to foster the stabilization of the world order from war and disputes, it is necessary to rethink globalization in ways that are more ethical and friendly to the world. On the topic discussion of global ethics, we learned about attempts by world organizations like the United Nations in generating international agreements including the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Besides, other agreements such as the Cairo and Bangkok Declarations represent local voices which to some points define human rights differently.

The difference in worldviews among international actors is interesting because each organization tries to define a global value within their own relativities. Moreover, some theories think that UN Declaration on Human Right is a Western domination over other cultures without considering cultural relativities, including religions, each of which inherits different theological and structures while at the same time sharing common values like peace, humanity, equality, and justice.

World issues indeed became valuable perspective in this class. Students are meant to not only understand theories but also keep updating their knowledge on what is happening in the recent international world. While negative influences of globalization such as war, religious radicalization, and other world disputes were discussed in the class, there is also a hope for a global agreement and bright future by sharing noble values like cooperation, justice, human dignity, and peace on global scale. The existence of world organizations and religious representatives in fostering global ethics proves the progress made towards creating world peace. The duty of students, in this case, is to contribute academically to spreading such values without neglecting the variety of cultural and religious perspectives.

*The writer is CRCS’s student of the 2016 batch.

Samsul Maarif | CRCS | Perspektif

Ibu Bumi wis maringi (Ibu Bumi sudah memberi)

Ibu Bumi dilarani (Ibu Bumi disakiti)

Ibu Bumi kang ngadili (Ibu Bumi yang mengadili)

La ilaha illallah, Muhammadun rasulullah (3x)

Pada 20 Mei 2016, “Doa Nusantara” ini dilantunkan oleh ribuan warga Pati sebelum dan saat melakukan aksi jalan kaki (long march) sepanjang 20 kilometer dari Petilasan Nyai Ageng Ngerang di Kecamatan Tambakromo menuju alun-alun Kota Pati untuk mengajak semua pihak melestarikan pegunungan Kendeng. Lantunan doa itu kembali menggema pada aksi long march berikutnya yang menempuh 150 kilometer dari Rembang ke Semarang pada 5-8 Desember 2016.

Mereka datang menuntut Gubernur Jawa Tengah Ganjar Pranowo untuk mematuhi putusan Mahkamah Agung yang pada 5 Oktober 2016 telah mengabulkan Peninjuan Kembali (PK) gugatan mereka atas izin lingkungan kepada PT Semen Gresik (kemudian menjadi PT Semen Indonesia). Doa itu terlantun kembali oleh Gunretno, koordinator Jaringan Masyarakat Peduli Pegunungan Kendeng (JMPPK), pada acara MetroTV, “Mata Najwa: Bergerak Demi Hak”, 21 Desember 2016. Sebelumnya, pada 11-13 April 2016, sembilan “Kartini Kendeng” menyemen kakinya di depan Istana Negara.

Rangkaian unjuk rasa yang tidak biasa itu adalah bukti bahwa para petani sungguh merasa terancam oleh pembangunan pabrik semen di wilayah tempat mereka tinggal di sekitar pergunungan Kendeng—dan mereka sudah menolak pembangunan pabrik semen sejak 2006. Kesungguhan itu lahir dari tradisi yang mengakar di masyarakat lokal, yang di dunia akademik biasa disebut “ekologi adat”.

Praktik Ekologi Adat Kendeng

Ekologi adat adalah rangkaian praktik dan pengetahuan adat yang menekankan kesatuan dan kesaling-tergantungan manusia dan lingkungan, yang mencakup berbagai wujud seperti tanah, hutan, batu, air, gunung, binatang, dan lain-lain. Dalam ekologi adat, eksistensi dan jati diri manusia bergantung dan hanya dapat dipahami dalam konteks relasinya dengan lingkungannya. Keberlanjutan hidup manusia identik dengan kelestarian lingkungan, dan kerusakan lingkungan adalah kehancuran manusia.

Ekologi adat adalah penyesuaian dengan istilah-istilah yang sudah berkembang dalam literatur akademis, seperti indigenous ecology, local ecology, traditional ecology, dan seterusnya. Salah satu inti dari bangunan pengetahuan tersebut adalah bahwa ekologi bukan hanya rangkaian pengetahuan (body of knowledge), melainkan juga cara hidup (way of life) (McGregor 2004). Wajar saja jika Komisi Dunia untuk Lingkungan dan Pembangunan (World Commission on Environment and Development/WCED) sejak 30 tahun lalu menegaskan pentingnya masyarakat modern belajar dari pengetahuan dan pengalaman masyarakat lokal/adat terkait pengelolaan lingkungan (WCED 1987).

Anang G. Alfian* | CRCS | Class Journal

Salah satu mata kuliah yang diajarkan di CRCS adalah Religion, Violence, and Peace Building (Agama, Kekerasan, dan Perdamaian). Tiga kata kunci ini menjadi variabel dan titik tolak diskusi tentang hubungan agama dan konflik sosial dan bagaimana upaya untuk membangun perdamaian.

Diampu oleh Dr. Iqbal Ahnaf, mata kuliah ini membahas, antara lain, persoalan relasi antara agama dan konflik. Ini dibahas di pertemuan pertama untuk membuka wawasan tentang perdebatan yang terjadi mengenai hubungan kausalitas antara agama dan kekerasan.

Pada pertemuan ini, satu dari dua bacaan yang dipakai sebagai bahan readings adalah artikel dari Andreas Hasenclever dan Volker Rittberger, Does Religion Make a Difference?: Theoretical Approaches to the Impact of Faith on Political Conflict (Journal of International Studies, 2000).

Dalam artikel itu, Hasenclever dan Rittberger memaparkan tiga mazhab dalam dunia akademik dalam membaca hubungan agama dan konflik, yaitu (1) primordialis, (2) instrumentalis, dan (3) konstruktivis.

Kaum primordialis berpandangan bahwa agama dalam dirinya sendiri memiliki unsur inheren yang dapat menyebabkan konflik. Ketika terjadi “konflik agama”, agama dibaca oleh kaum primordialis sebagai variabel yang independen, unsur yang tidak bergantung pada aspek-aspek lain, dan perbedaan identitas keagamaan itu sendiri bisa cukup sebagai penyebab konflik.

Kaum instrumentalis melihat peran agama dalam “konflik agama” sebagai instrumen saja, dan tidak memiliki peran objektif dalam dirinya sendiri. Menurut kaum instrumentalis, penyebab utama konflik adalah kepentingan politik dan ekonomi. Bagi kaum instrumentalis, agama hanya berperan dalam retorika saja, dan relasinya dengan konflik bersifat semu belaka.

Kaum konstruktivis tampak berada di tengah-tengah antara kedua kelompok di atas. Konstruktivis bersetuju dengan instrumentalis dalam hal bahwa penyebab fundamental konflik bukanlah agama, melainkan kepentingan politik dan ekonomi. Namun konstruktivis juga bersepakat dengan primordialis dalam hal bahwa agama memiliki peran nyata objektif, namun bukan sebagai penyebab utama, melainkan eskalator konflik. Agama, ketika terlibat dalam konflik, dapat membuat konflik semakin mematikan, deadly. Juga, berbeda dari primordialis yang berpandangan bahwa agama menjadi variabel independen dalam konflik, bagi kaum konstruktivis agama berperan secara dependen, tergantung pada faktor-faktor ekonomi dan politik lain yang melingkupi konflik tersebut; seberapa besar peran agama mengeskalasi konflik tergantung pada seberapa akut benturan antar kepentingan politik dan ekonomi dalam konflik itu.

Ketiga cara pandang di atas tidak bisa diperlakukan secara universal. Tapi ketiganya bisa dijadikan lensa analitis dan ditempatkan dalam suatu spektrum. Bagaimana menentukan peran agama dalam suatu konflik mestilah dimulai dari detil kasus konfliknya, lalu naik melihat lensa-lensa analitis yang ada, kemudian menentukan di antara yang tersedia manakah penjelasan yang lebih tepat.

Dalam “kasus Sunni-Syiah” Sampang, misalnya, dimensi konflik yang terjadi bukan hanya karena faktor perbedaan ideologis semata, namun juga karena adanya instrumentalisasi agama oleh elite politik, karena konflik ternyata bereskalasi pada masa perebutan kekuasaan menjelang pemilu daerah, sehingga narasi-narasi agama di legitimasi sedemikian rupa untuk suatu tujuan politik. Dalam melihat hal ini, kita tak bisa berhenti pada pandangan kaum primordialis—inilah pandangan yang diadopsi oleh mereka yang memercayai bahwa konflik Sampang itu adalah konflik Sunni-Syiah. Dimensi sosial politik dalam konflik itu wajib dihitung, mulai dari yang kecil seperti persengkataan internal keluarga, perebutan umat, hingga yang lebih makro seperti instrumentalisasi konflik untuk mendulang dukungan dalam pemilu.

Dalam perspektif konstruktivis, intervensi terhadap konflik dengan menyuarakan nilai-nilai kebajikan agama, kearifan lokal, dan slogan-slogan orang Madura Sampang sangat membantu upaya rekonsiliasi konflik, yakni untuk melakukan deskalasi terhadap konflik itu dengan mengajukan narasi tandingan primordialis. Penelitian Dr. Iqbal Ahnaf beserta peneliti yang lain dalam serial laporan CRCS tentang kehidupan beragama di Indonesia yang bertajuk Politik Lokal dan Konflik Keagamaan menunjukkan instrumentalisasi agama oleh elit politik di Sampang menjelang pilkada. Tesis S2 terkait kasus Sampang ini juga ditulis oleh mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2010 Muhammad Afdillah yang kini telah dijadikan buku dengan judul Dari Masjid ke Panggung Politik.

Kasus Sampang merupakan contoh yang bagus untuk membaca seberapa besar peran agama dalam konflik, dan ini membutuhkan data dan analisis yang cermat. Contoh-contoh lain dari yang terjadi di Indonesia yang bisa diambil ialah kasus Ambon dan Poso, atau yang belum lama ini terjadi seperti di Tolikara, Tanjungbalai, atau bahkan kasus dugaan “penodaan agama” dalam pilkada Jakarta.

*Penulis adalah mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2016

Ilham Almujaddidy & A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Event Report

Dialog antaragama sebagai upaya penyelesaian konflik bukan hal yang mudah dilakukan. Tidak jarang terjadi, dialog yang dimaksudkan untuk menjembatani perbedaan dan meminimalisasi konflik tidak berjalan sesuai tujuan awal, atau bahkan kontraproduktif dan menimbulkan masalah baru.

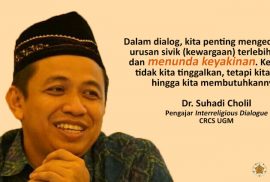

Dalam diskusi Forum Umar Kayam, Pusat Kebudayaan Koesnadi Hardjosoemantri (PKKH) UGM, pada Senin 25 Juli 2016, dosen CRCS Dr. Suhadi Cholil membahas persoalan ini. Dalam diskusi bertajuk “Menunda Keyakinan: Refleksi Membangun Pluralisme dari Bawah” itu, pengajar matakuliah Interreligious Dialogue di CRCS ini memberikan identifikasi-identifikasi penyebab dialog gagal mencapai tujuannya.

Pertama, kurangnya pemahaman substantif tentang fungsi dan metode dialog antaragama yang menyaratkan, antara lain, adanya saling percaya. Adanya praduga-praduga negatif terhadap mitra dialog dapat menimbulkan tiadanya saling percaya itu, dan pada gilirannya menjadi hambatan utama bagi efektivitas proses dialog.

Kedua, dialog antaragama yang semestinya menjadi interaksi untuk saling mengakomodasi masing-masing pihak yang terlibat, dalam prosesnya, malah terjebak dalam upaya untuk mendominasi.

Ketiga, dialog antaragama diandaikan sebagai penuntas konflik. Yang jarang dipahami, dialog dalam praksisnya tidak serta merta bisa menyelesaikan konflik. Beberapa konflik, apalagi konflik agama yang melibatkan klaim-klaim teologis yang sulit untuk dijembatani, tidak mudah dimediasi dengan dialog semata, dan karena itu memerlukan alternatif resolusi konflik yang lain.

Dengan menyadari hal-hal yang menghambat dialog antaragama itu, pemahaman yang tepat mengenai fungsi dan metode dialog antaragama bagi para pihak yang terlibat di dalamnya mutlak diperlukan, termasuk mensinergikan pengetahuan teoretis dan praksis.

Yang kerap menjadi problem di lapangan ialah banyak akademisi yang hanya fokus pada persoalan-persoalan teoretis atau teologis semata, namun abai pada ranah praktis. Sementara di sisi lain, ada banyak aktivis yang kurang reflektif secara teoretis maupun teologis, namun begitu aktif di pelbagai aktivitas dan advokasi perdamaian. Ketika kedua belah pihak ini terlibat dalam sebuah dialog, kerap kali muncul kesalahpahaman yang dapat memicu timbulnya permasalahan baru, dan karena itu kontraproduktif.

Hal lain untuk meminimalisasi hambatan dalam dialog antaragama ialah dengan mendudukkan isu teologis secara tepat. Tidak dapat dimungkiri, isu teologis merupakan isu sensitif, dan karena itu, jika tak hati-hati, justru dapat merusak proses dialog itu sendiri. Dalam proses dialog antaragama, isu teologis berada dalam ketegangan antara klaim eksklusifitas dan kehendak untuk menerima adanya keyakinan yang berbeda.

Dalam persoalan yang terakhir ini, Dr. Suhadi tidak mengusulkan untuk membuang eksklusivitas itu. Baginya, eksklusivitas itu sendiri tidak salah dalam dirinya sendiri. Ia akan menjadi masalah ketika tidak diterjemahkan dengan proporsi yang tepat di ruang publik. Banyak dari yang terlibat dalam proses dialog tidak membedakan antara ruang privat untuk ranah teologis dan ruang publik untuk pencarian titik temu guna menyelesaikan konflik. Karena kurangnya pemahaman untuk melokalisir klaim-klaim teologis pada ranah pikiran dan hati, dialog antaragama, alih-alih menjembatani perbedaan, justru rawan menjadi adu klaim teologis.

Merespons isu eksklusivitas teologis dalam dialog antaragama ini, Dr. Suhadi menawarkan gagasan bahwa untuk mengembangkan dialog antaragama yang lebih produktif, perspektif yang terbaik adalah dengan mendahulukan urusan sivik (kewargaan) dan menunda keyakinan. Hal ini tentu tidak berarti keyakinan ditinggalkan. Keyakinan ditunda, tidak dikedepankan, dan baru ditengok kembali ketika dibutuhkan dalam proses dialog.

*Laporan ini ditulis oleh mahasiswa CRCS, dan disunting oleh pengelola website.

Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Article

“Jesus as an infant fled with his family into exile. During his public life, he went about doing good and healing the sick, with nowhere to lay his head”.

We were finally in the next to last meeting of Religion and Globalization class. Having studied religion and globalization through the whole sessions, we have come to understand a lot about what role of religions play in accord to globalization and how globalization affects the way religions are concerned with humanitarian issues.

On Monday, November 21, 2016, we had a field trip to one faith-based-NGO to understand how such religious organization works for humanity. Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is one of the well-known international organizations and it was a good place to learn the working field of faith-based organizations. Together with Gregory Vanderbilt as the lecturer of the class, we visited the national office of JRS in Yogyakarta and had a great time meeting Fr. Maswan, S.J., and learning directly from a member of the community

Our visit began with Fr. Maswan’s presentation about the organization. Firstly established in Indonesia in 1999, Jesuit Refugees Services has been accompanying, advocating, and giving services to forcibly displaced people. Therefore, this organization has actually been well experienced in dealing with the issues. As we listen to his presentation, we come to realize that this problem of refugees and asylum seekers cannot be ignored for it belongs to international concern. The perpetuation of war, disasters, racial conflict, and many other causes make refugees seek for their safety life by migrating to other national boundaries.

Our visit began with Fr. Maswan’s presentation about the organization. Firstly established in Indonesia in 1999, Jesuit Refugees Services has been accompanying, advocating, and giving services to forcibly displaced people. Therefore, this organization has actually been well experienced in dealing with the issues. As we listen to his presentation, we come to realize that this problem of refugees and asylum seekers cannot be ignored for it belongs to international concern. The perpetuation of war, disasters, racial conflict, and many other causes make refugees seek for their safety life by migrating to other national boundaries.

However, it has never been easy for refugees because they have to face the legal and often difficult administrative regulations of the government where they are staying. This is exactly what happens to refugees in Indonesia. Because Indonesia has not ratified the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, refugees in Indonesia are not recognized as such by the Indonesian government—instead they are considered undocumented aliens—while they wait for recognition from the UNHCR which will allow them to resettle in another country. In some districts, refugees have to stay in detention center while waiting for their legal refugee status to be acknowledged by the law.

As recorded in JRS monitoring, refugees in Indonesia have reached a number of 4.344 people of whom 540 are female and 905 are children with 96 being unaccompanied minors and seperated children. So far, JRS has been accompanying two detention centers in Surabaya and Manado and being involved in other areas as well. In Aceh, JRS has advocated for protection over 625 people and has given psychosocial accompaniement to over 1558 refugees. In Yogyakarta, they are serving the refugees, mostly from Afghanistan, housed in the Ashrama Haji. They listen, accompany, and make activities to give hope for those people who had been separated from their family and their mother land.

So, where is exactly the religion to deal with this? This question come out of students trying to figure out the role of religion in this humanity organization. Then, the community member continued the presentation stating that the mission of JRS is intimately connected with the mission of Society of Jesus to serve faith and promote the justice of God’s kingdom in dialogues with cultures and religions. Yet, another student comes up with another concern, “Does it mean that JSR proselytize Christianity?” Well. This is very important because in the previous meeting, we read through Philip Fountain’s “Proselytizing Development” and he himself attended our class for discussing this topic. In sort, the religion has been inspired by the development organization as precedent in history while, vice versa, religion brings universal ethics to be put in dialogue with cultures and religion.

In the last session of our discussion in JRS offices, Fr. Maswan emphasized some points such as it is the problem of humanity that we have to be concerned about and not at all concerned in religious kind of missionary work altough it might inspired the organization in its underlying ethics, building cooperation with other cultural, faith-based, and other types of organization. We also read the paper Fredy Torang (2013 batch) presented in Singapore about how JRS acts as an agent of “humanitarian diplomacy” between the refugees and the local communities and government. In 2017, JRS will continue lobbying local government to allow refugees to live in a community and not in detention and also monitoring the migration all over the world to help assisting the displaced people and consistently gives concern to human right and dignity.

In the last session of our discussion in JRS offices, Fr. Maswan emphasized some points such as it is the problem of humanity that we have to be concerned about and not at all concerned in religious kind of missionary work altough it might inspired the organization in its underlying ethics, building cooperation with other cultural, faith-based, and other types of organization. We also read the paper Fredy Torang (2013 batch) presented in Singapore about how JRS acts as an agent of “humanitarian diplomacy” between the refugees and the local communities and government. In 2017, JRS will continue lobbying local government to allow refugees to live in a community and not in detention and also monitoring the migration all over the world to help assisting the displaced people and consistently gives concern to human right and dignity.