"Terrorism is born out of an identity crisis as a result of a complex situation that has made the terrorists unable to behave like normal people."

Terrorism

Abstract

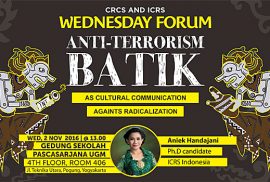

Acknowledged by UNESCO in 2009 as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, batik is produced through an introspective creative process in which the artist uncovers a truth and presents local wisdom and beauty. In this way, it can be an effective means to communicate symbols, ideas and messages about peace, respect and interreligious tolerance in order to counter the growing radicalism in Indonesian society. Aniek Handajani will present her new book Batik Antiterorisme Sebagai Media Komunikasi Upaya Kontra – Radikalisasi Melalui Pendidikan dan Budaya (co-written with Eri Ratmanto and published by UGM Press, 2016) as well as several works of batik she has commissioned in order to encourage public discussion about terrorism and peace.

Speaker

Aniek Handajani is a staff at the East Java provincial office of the Ministry of Education and an English lecturer at the Faculty of Education, Islamic University, Lamongan. She earned her Masters in Education at Flinders University in Australia and is an educator and activist for inter-religious peace. Currently, she is a Ph.D. candidate at Inter-Religious Studies (ICRS), UGM, researching terrorism and deradicalization.

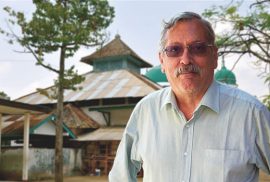

Two of the most challenging questions faced by those promoting freedom of speech is to what extent speech is free and whether there are kinds of speech which should be restricted. Very often this brings about a dilemma, since restriction can be seen as the opposite of freedom. This is partly because there are people who can utilize the freedom of speech to spread hatred or incite harm to other people or to the well-being of society in general. The question: Is there room for hate speech within free speech? How should hate speech be defined? On February 15, 2016, CRCS student Azis Anwar Fachrudin interviewed Mark Woodward on the question of religious hate speech. Woodward is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Arizona State University (ASU) and is also affiliated with the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict there. He was a Visiting Professor, teaching at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS), Gadjah Mada University, for several years. He has written books related to Islam in Java and Indonesian Islam in general, as well as more than fifty scholarly journal articles, including “Hate Speech and the Indonesian Islamic Defenders Front” co-authored with several others including CRCS alumnus Ali Amin and ICRS alumna Inayah Rohmaniyah and published by the ASU Center for Strategic Communication in 2012. On February 17, 2016, he presented in the CRCS/ICRS Wednesday Forum, on the subject of “Hate Speech and Sectarianism.”

Two of the most challenging questions faced by those promoting freedom of speech is to what extent speech is free and whether there are kinds of speech which should be restricted. Very often this brings about a dilemma, since restriction can be seen as the opposite of freedom. This is partly because there are people who can utilize the freedom of speech to spread hatred or incite harm to other people or to the well-being of society in general. The question: Is there room for hate speech within free speech? How should hate speech be defined? On February 15, 2016, CRCS student Azis Anwar Fachrudin interviewed Mark Woodward on the question of religious hate speech. Woodward is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Arizona State University (ASU) and is also affiliated with the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict there. He was a Visiting Professor, teaching at the Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS), Gadjah Mada University, for several years. He has written books related to Islam in Java and Indonesian Islam in general, as well as more than fifty scholarly journal articles, including “Hate Speech and the Indonesian Islamic Defenders Front” co-authored with several others including CRCS alumnus Ali Amin and ICRS alumna Inayah Rohmaniyah and published by the ASU Center for Strategic Communication in 2012. On February 17, 2016, he presented in the CRCS/ICRS Wednesday Forum, on the subject of “Hate Speech and Sectarianism.”

***

Hate speech is quite complex to define, but if someone asks you about it, how would you first define and explain it?

There is no any academic or political consensus on what is and what is not hate speech. It varies considerably from one country to the next when we’re thinking about it in political or legal ways. I think though that we can say that hate speech does two things. It treats or defines people as being less human and in higher level involves demonization. And that’s sometimes quite literal. One of the reasons why I use FPI [Islamic Defenders Front; in Indonesian, Front Pembela Islam, abbreviated as FPI] as an example is that it is so clear when they say, for example, Azyumardi is iblis [the devil]…

Or Ahok is kafir [an infidel] … this counts as hate speech?

Yes, calling people iblis is one level up. At its highest level, hate speech is defining people as archetype of evil. Once you define people in these ways, then you’re just defied, at least in your mind, in calling for the organization to be outlawed. Sometimes, [you’re called] to kill them. We’ve seen that.

So, there are scales of hate speech…

Ya, scales. Lower level of hate speech would be simply saying that a group or an individual is sesat or deviant, and it moves up from there… at the highest level it calls “kill them!” Literally calling for violence. In almost any level it can be used to justify violence; it can be used for purposes of political mobilization. That’s particularly powerful when it’s used by either large NGOs or by governments.

Your paper is opened by a quite provocative statement. It says, “FPI is a domestic Indonesian terrorist organization.” How can you say that it’s terrorist?

It is a terrorist organization; it deliberately seeks to terrorize people. Terror is a state of mind; it is a psychological and sociological term. It is spreading extreme fear in people. This is what FPI does…

But they would certainly reject to be called terrorist…

Most certainly they reject it, so does Jamaah Islamiyah; they would respond that they weren’t terrorist; they were mujahidin. No one, or very few people, will say “I am a terrorist.” But look at what they do, though. They threaten people; they terrify, beat and sometimes kill them. I have no problem calling them terrorist at all.

So you’re prepared to take the risk of saying that.

I’m perfectly prepared to call them terrorists. This is an academic judgment. I know that there are people who for political reason would restrict the use of terrorism, to think like suicide bombing. But that’s a political judgment, not an academic judgment.

To support your thesis, you’re collecting data from what FPI has done to particularly Ahmadis and those who are considered to be deviant…

Anyone they consider to be deviant… and people who don’t fast during Ramadan, or gay and lesbian people, and increasingly Shia…

But I think there’s one thing quite important from [FPI founder] Habib Rizieq as he was once giving a sermon, I watched it on Youtube, in which he’s making three categories of Shiites (Ghulat, Rafidah, Mu’tadilah). Have you made a note about this?

I have not seen that. I very much like to. Habib Rizieq has been somewhat more reluctant to be critical of Shia than he has of Ahmadiyah and liberals. Most of the examples that we use in that paper are about liberals. It has been successful to the extent that people are now very reluctant to call themselves liberals. If you’re calling yourself a liberal, you’re putting yourself at risk.

Actually the attackers of Shiites in Sampang were not FPI, right? And this is particularly because FPI has a view on Shia that is different from theirs.

There are a lot of different organizations that are behind anti-Shia, as well as anti-Ahmadiyah. One of the alarming features of this is that hatred toward Shia has brought people who normally would not be on the same side. Very good example of that is, if you look at Forum Umat Islam and their publication called Suara Islam, then you look at the editorial board… you have Habib Rizieq, and you have [Jamaah Ansharut Tauhid’s leader] Abu Bakar Baasyir. And Baasyir is Salafi-Wahabi.

Salafi-Wahabi?

It’s clear from what he has written; it’s clear from the people he denounces. He speaks frequently and forcefully about concepts like bid’ah, khurafat, syirik, denouncing ziarah kubur, and things like that. And Habib Rizieq is… habib… (who likes to gather people to do) salawat…

Closer to NU in terms of rituals…

Closer to NU, and to other habibs [a title typically referring to Prophet Muhammad’s descendants]. I’ve been to events at the masjid and bazaar near FPI and you have salawat, you have maulid, all the things… If you went to see Habib Luthfi, you would see the same sort of ritual. So this is a new development in political Islam in Indonesia. You would find those groups on the same side; it is really only hatred of someone else that brings them together.

A common enemy creates a new alliance…

That’s right. “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

One of your main theses in that paper is that the government cannot stop FPI violence because it fears appearing non-Islamic. Does that imply that what FPI has done is actually in accordance with the common will of the people they’re trying or pretending to defend?

That’s a very difficult question. It does seem to be clear that at least at the beginning—maybe no longer true—FPI was linked to elements within the police and military. I don’t think that the majority of Indonesians support the sweepings. We haven’t seen these recently as much as we had; they were for a while. But there are many people who are afraid to oppose them publicly because there are threats.

Because of threats or because what FPI is doing is Islamic?

Well, there are people who would agree with what they say, but not agree with their methods. There are people who would be very strong political opponent of Shia and Ahmadiyah on religious ground, but they would not consider violence to be justified. We need to be very clear on those differences. The issue is not whether or not you agree with someone’s religion. I may not agree with Salafi-Wahabi teachings, but I’m not going to go and say that they should be killed. It’s criminality, not theology. It’s actions that are important… or inciting violence. That’s very complicated and you’ll question. There is a paradox, between controlling hate speech and defending free speech. This is a paradox that has no clear resolution; no easy answer.

I think one of the political strategies to minimize or to stop FPI violence is to cut the ties between FPI and the police.

Well, that’s definitely one thing that needs to be done. I don’t even know whether this still operates. Certainly the police are not willing to clamp down on them very hard. There are some people who think that if they did, it would only get worse. There are other people who think they don’t have the power to do that. But I don’t believe that. Because the Indonesian security forces have proven themselves to be extremely effective in cracking down groups like Jamaah Islamiyah. If they wanted… if they decided to shutdown FPI, they could. I don’t have any doubt about that. FPI does have a much broader basis of support than Jemaah Islamiyah. Because they are not talking about things like establishing a caliphate…

They are talking more about amar ma’ruf nahy munkar [Quranic injunction to “enjoin what is right and forbid what is wrong”]…

Yeah, and they are talking about aliran sesat [heretical movements].

And basically it doesn’t have a problem with Pancasila, right?

No, it doesn’t have a problem with Pancasila. Honestly, groups like FPI and partly MMI are more difficult to deal with than Jamaah Islamiyah…

Because they can operate within the government…

Because they can operate within the government… and they can operate basically within the framework of things that are considered to be religiously acceptable. Being habib has a great deal of prestige.

Rizieq’s “habib-ness” makes a great deal…

His habib-ness is part of what gives him religious authority for many people. This is certainly true of many of his followers…. preman [gangsters], and some mantan preman.

Coming back to the topic of hate speech. Do you think Indonesia should have a law banning hate speech, such as calling others as kafir or…?

There are some regulations that were issued by the national police; no one pays any attention to them. But I think this is a political choice that only the people of Indonesia can make. No matter what choice they make, there will be people who will be critical. And again, if you look at this in a world wide way, in functioning democracies, you’ll find, for example, in the United States you can say the most terrible thing you want. But in Germany, if you say anything good about Nazis or if you display Nazi symbols, you get arrested. There is a wide range of strategies.

Yeah, limits on free speech create new dilemmas…

Right, that’s absolutely right. A strong government would not tolerate hate speech. On the other hand, maybe there are other people who would say this is a price we have to pay for democracy. This is where the paradox comes. Democracy is always messy and noisy.

Would you prefer to say that, for example, [rising FPI leader] Sobri Lubis who was saying that it is lawful to shed the blood of Ahmadis should not be punished?

He probably crosses the line, because he very clearly says kill the people and directly incites a crime. I don’t think it causes problem with free speech to prosecute people who encourage others to kill people. This is probably the line. Actively encouraging violence is probably the line.

So, one line that, I think, can be agreed on by all people is inciting physical violence, right?

I think so. I think you could have a broad consensus of opinion that says that this (encouraging violence) is too much.

One last question. Since you’re mostly dealing with FPI, would you further your research to reach other cases such as, the most recent, Gafatar in Kalimantan Barat and Ahmadiyah in Bangka? They are not done by FPI, but people around them.

Yes. An important question here is, what are the social processes at work? In the last ten years, there has been a climate that promotes or indirectly promotes this kind of thing; that it becomes socially acceptable in ways that it probably would not have been before. Ahmadis have been in Indonesia peacefully for more than a hundred years. Both Muhammadiyah and NU have issued fatwa that said this is sesat. Nobody did encourage any kind of violence. Shia? No one cared at all, because the Shia didn’t bother any body. All these have been an invented crisis in the last ten years. Who is kambing hitam here? Belum jelas.

Do you think that it has something to do with, like some would say, Wahhabism?

Well, partly. It’s definitely a global phenomenon. The paper that we’re talking about is part of a global research project. And we have seen the same thing in Nigeria, which is a country where there are no Ahmadis and Shia. People there are going around, talking about the danger of the Shia… even though there are no Shias! It is in one way a global phenomenon.

Ok, Pak Mark. That’s all. Thank you so much.

Azis Anwar Fachrudin | CRCS | Interviews

Ali Jafar | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Maurisa, a CRCS alumna from the batch of 2011, presented her award-winning paper in Wednesday forum of CRCS-ICRS in 11th November 2015. Her paper entitled “The Rupture of Brotherhood, Understanding JI-Affiliated Group Over ISIS”, was awarded as best paper in IACIS (International Conference on Islamic Studies) in Manado, September. Maurisa was glad to share her paper with her younger batch. To all the audiences, Maurisa told that winning as best paper was not her high expectation, and it makes her proud.

The presentation began with Maurisa’s statement that the issue of ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) are quite to understand in relation to modern terrorism, because we always misread them and sometime we cannot differentiate between ISIS and Al-Qaeda. Maurisa continues her explanation that there are many groups in Iraq and Syria struggling for their power, terrorism is not single but many. ISIS also has supporters in Indonesia such as Jemaah Islamiyyah (JI-Islamic Group) which is considered as a big terrorist organization in Southeast Asia. This group (JI) has disappears from public consciousness, but actually its members have been spreading out. The most fascinating thing that she found is that JI in Indonesia. JI was separated into two, Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia (MMI) and Jama’ah Anshar at-Tauhid (JAT), and surprisingly JAT itself has internal conflict and divided into two; JAT and JAS (Jama’ah Anshar as Syari’ah).

Maurisa’s paper focused on questions about how does the conflict in Syria resonates with Jihadists in Indonesia, and how does political struggle within MMI show belief in a master narrative. Maurisa used Juergensmeyer’s perspective about cosmic war and the logic of religious violence. In the Juergensmeyer perspective, an ordinary conflict could become religious conflict when it is raised into cosmic level. One of the ways is demonization or Satan-ization of the enemy. In the context of Syria, the demon is Shia group which is blamed for chaotic situation within Sunni community. The master narrative was also about the same language. It is about sadness, it is about the sad feeling of being discriminated and persecuted by Shia.

According to Maurisa, not all jihadist groups support ISIS, indeed MMI was supporting Jabhat an-Nusra. The rupture of this affiliation was based on their differences in the perspective of takfirism (Apostasy). JAT and MMI have different perspectives in defining what Takfir Am (general apostasy) and takfir Muayyan (specific apostasy) is.

In seeing terrorist movements, although Maurisa saw that Jihad-ism is not monolithic, she revelas that there are five elements which are related each other. There are ideological resonance, strategic calculus, terrorist patron, escalation of conflict and the last is charismatic leadership. Terrorists also use social media, such as Facebook, Youtube and so on, to promote their propaganda, and as soft approach to other Muslims. Based on Maurisa’s research there are 50000 social media accounts to spread ISIS propaganda, but only 2000 are used to spread out propaganda. The most popular social media is Twitter, because a message can be retwited..

In the discussion session, Nida, a CRCS student asked about the current issues in which governments have banning Shi’a celebration in Indonesia, and whether there is any relation with ISIS, and how an Indonesian can be involved in the terrorism. Maurisa answered the question by explaining that Indonesia is about to change. It can be seen in Islamization created room for Islam in the public sphere. Indonesia is vulnerable since Wahabis and Iran have their political goals here and both want to establish their domination to spread out their agenda. Cases in Sampang, Madura, Pakistan and so on cannot be separated from international case. There are long story for transformation of Saudi and Iran. Our country is like something too. In talking about the entrance gate, Turkey is good entrance from Indonesia to go to Syria. If we see Turkey’s position is also questionable. They deny Isis, but they also support Isis.

Subandri also asked about the ways we interpret jihad are accessible. Therefore there are many interpretations of Jihad. That is what looks like for young Muslim now. Along with Subandri, Ruby also asked about the genealogy of Indonesian Jihadist movement. Like the connection between Indonesia and middle east that coming and potential realignment and the effect of JAT over ISIS.

In seeing connection and global phenomena, a relation between Islam and Middle East, Maurisa explained that in the United State for instance, there is relation if you wear jilbab, you are Muslim, and when you are Muslim, you are ISIS. “Here we can see the idea about securitization is like Islamophobia”, said Maurisa with showing slide about relation between Indonesia and Middle East. As she explained again “If we look at voice of Islam, we can see that there are solidarities for Syria. It is reported that medical mission in Indonesia, they have collected 1.6 million. For Syria suggesting support for the movement of mujahidin”. Maurisa also explained that globalization is the most responsible for this case. For example many Indonesia Muslims have easy access to Saudi, Iranian, Jihadist web, because of technology and so on. Young Indonesian have a lot of curiosity and they don’t ask to other.

In responding the interpretation of jihad, Maurisa gives a feedback, how do we interpret this? What makes cosmic war happen? And how to deal with them?. Maurisa began her explanation that in Islam, although there are many verses for killing, but it not necessary to do in violence. We have many steps in interpretation. There are many reasons for what make Muhammad approve of killing and in what context he did so. There are many possibilities to interpret jihad and there are many verses of good thing about Jihad. In talking about cosmic war, she said that “as long as we consider our enemy as Satan, or evil, meaning it is cosmic war”. At the end of discussion session, Maurisa concluded that the factor of jihad is not monolithic; there are many factors, even in ISIS and Al-Qaeda have different perspectives about jihad.

(Editor: Gregory Vanderbilt)