Anang G Alfian | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

At the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on April 12th, 2107, Sawyer Martin French, a research fellow at the Institute for International Studies at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Universitas Gadjah Mada, gave presentation on the government-mandated curricula of Islamic education in public high schools. He took several public high schools (Sekolah Menengah Atas, SMA) in the province of Yogyakarta, with the method of classroom observation, interviews with teachers, and student focus group discussions in a few schools. More importantly, he also presented his research on Islamic textbooks used in those high schools which he observed have undergone content changes.

In his presentation, French showed that each political period has a difference in the emphasis of the contents of the Islamic textbooks used in SMA. There are three political periods where curricula for Islamic education in SMA have evolved, from the 1994 curriculum, which was formed under the Suharto New Order’s regime; then replaced by the 2006 curriculum under the post-reformation period; and the latest, 2013 curriculum. French shows the content of the Islamic curricula has undergone several changes, three main of which are that related to tolerance, democracy and gender issues.

Regarding democracy, French mentioned an example of 1994 Islamic textbook mentioning the importance of “mushawarah” (lit. consultation to each other) as an Islamic teaching in managing Indonesian politics and governmental administrations. The 2003 textbook mentioned the importance of being a good citizen, meaning a democratic citizen, by further interpreting the meaning of mushawarah. This shows the change due to discourse on democracy generated by reformation. In the 2013 textbook, there is a reference to put more details of how Indonesia democracy should take the ideal shape, and that is to take the example set by the Medinan charter during the time of the Prophet.

Relating to tolerance, the textbooks show changes in the way Muslim should deal with other religions or Islamic sects. In the 1994 textbook, Pancasila was referred to as be the basis of harmony among religious communities while in the 2006 textbook, tolerance can be built along social matters but not along religious lines. The 2013 textbook mentioned that tolerance is a tool to unite the nation, but there are a few sentences which suggest intolerance against some Islamic sects, such as that some Sufi orders practice bid’ah or heretical rituals and that Shiites and Ahmadis are deviant and beyond the limit of tolerance.

As on gender issues, the dominant content of the 1994 textbook upholds the obligation of men as the leader of the family and women as the one who must be obedient to her husband. This was set as an example of a good family. In the 2013 textbook, the focus was more to a companionate marriage and mutual relationship. The notions of housewife and superiority of men which were mentioned in the previous textbooks are now gone and replaced by sentences suggesting a more equal relationship between the husband and the wife, though there is still an emphasis that, despite the same level, “their roles are different.”

*Anang G Alfian is CRCS student of the 2016 batch

Headline

Redaktur Web | CRCS | Berita

Dalam aturan perundang-undangan, para penghayat kepercayaan atau penduduk yang agamanya “belum diakui” diminta untuk tidak mengisi kolom agama dalam Kartu Tanda Penduduk (KTP), “tetapi tetap dilayani dan dicatat dalam database kependudukan”.

Namun pada kenyataannya di lapangan, para penghayat kepercayaan yang mengosongkan kolom agama di KTP tidak mendapatkaan pelayanan yang setara sebagaimana warga negara pada umumnya, bahkan mengalami diskriminasi.

Kenyataan itu mendorong sejumlah pemohon mengajukan pengujian undang-undang (judicial review) ke Mahkamah Konstitusi (MK). Para pemohon yang berasal dari kepercayaan Marapu (Sumba Timur), Parmalim (Sumatera Utara), Ugamo Bangsa Batak (Sumatera Utara), dan Sapto Darmo (Jawa) memohon judicial review terhadap Undang-Undang Nomor 23 Tahun 2006 tentang Administrasi Kependudukan (UU Adminduk) jo. Undang-Undang Nomor 24 Tahun 2013 tentang Perubahan atas UU Adminduk 2006.

Beberapa dari perlakuan diskriminatif yang menimpa para pemohon berupa ketidaksetaraan dalam akses terhadap pekerjaan, akses terhadap hak atas jaminan sosial, dan tidak diakuinya perkawinan adat mereka yang berimbas pada akta kelahiran anak dan pendidikannya. Dalam beberapa kasus juga ditemukan stigma-stigma negatif dalam kehidupan sosial mereka. Dalam kasus lain ditemukan ada yang terpaksa mengisi kolom agama dengan agama yang bukan kepercayaannya agar administrasi pembuatan KTP “lebih mudah”.

Para pemohon menilai bahwa pengosongan kolom agama untuk pemeluk agama yang “belum diakui” bertentangan dengan prinsip kesetaraan warga negara di depan hukum. Para pemohon juga menekankan bahwa kebebaasan dari perlakuan diskriminatif telah dijamin oleh Undang-Undang Dasar, UU Hak Asasi Manusia Tahun 1999, dan Kovenan Internasional Hak-hak Sipil dan Politik yang telah diratifikasi Indonesia.

Dalam rangkaian judicial review di MK itu, salah satu dosen Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (CRCS), Dr. Samsul Maarif, hadir sebagai salah satu saksi ahli pada Rabu 3 Mei 2017. Alumnus dan kini pengajar di CRCS ini meraih gelar Ph.D. dari Arizona State University pada 2012 dengan disertasi tentang praktik keagamaan masyarakat Ammatoa di Sulawesi Selatan.

Di hadapan 9 hakim konstitusi, Samsul menguraikan hubungan negara, agama, dan kepercayaan yang tidak bisa dilepaskan dari konteks sejarah politik Indonesia. “Sejarah relasi negara, agama, dan kepercayaan senantiasa berada dalam konteks politik rekognisi,” demikian ujarnya sebagaimana terkutip dalam Risalah Sidang MK.

Presentasi Samsul memaparkan bahwa pada era Orde Lama, agama didefinisikan dengan sangat eksklusif, yaitu yang memiliki kitab suci, nabi, dan pengakuan internasional. Definisi ini menjadi penentu siapa yang dilayani (penganut agama “resmi”) dan siapa yang tak dilayani (penganut kepercayaan). Pemerintah Orde Lama bahkan membentuk Pengawas Aliran Kepercayaan (PAKEM) pada 1953.

Meski mendapat pengawasan, para penganut aliran kepercayaan berhasil berkonsolidasi. Departemen Agama pada waktu itu melaporkan bahwa pada 1953 telah ada 360 organisasi Kebatinan/Kepercayaan. Terwadahi dalam Badan Koordinasi Kebatinan Indonesia (BKKI), organisasi-organisasi kebatinan itu berhasil menyelenggarakan kongres pertama pada 1955 dengan ketuanya Mr. Wongsonegoro, salah satu perumus UUD 1945.

Pergolakan politik sempat terjadi pada 1965. Pada tahun ini lahir Penetapan Presiden (yang nantinya menjadi UU PNPS 1/1965 tentang Penodaan Agama) yang ingin melindungi agama dari penodaan oleh aliran kepercayaan. Setelah peristiwa 30 September 1965, aliran kepercayaan mendapat tekanan besar: mereka dicurigai sebagai bagian dari komunisme.

Nasib penghayat kepercayaan sempat membaik ketika pada 1970 Golkar membentuk Sekretariat Kerja Sama Kepercayaan (SKK). BKKI lalu bertransformasi menjadi Badan Kongres Kepercayaan Kejiwaan Kerohanian Kebatinan Indonesia (BK5I). Pada 1973 TAP MPR tentang GBHN menyatakan bahwa agama dan kepercayaan adalah ekspresi kepercayaan terhadap Tuhan YME yang sama-sama “sah”, dan keduanya “setara”.

Momen yang paling berimbas terhadap nasib aliran kepercayaan terjadi pada 1978. Pada tahun ini keluar Ketetapan MPR yang menyatakan bahwa kepercayaan bukanlah agama, melainkan kebudayaan. TAP MPR Nomor 4 Tahun 1978 ini juga mengharuskan adanya kolom agama (yang wajib diisi dengan salah satu dari 5 agama) dalam formulir pencatatan sipil. Mulai tahun inilah kolom agama tercantum dalam KTP. “Pada periode kedua Orde Baru, mulai 1978, agama mulai ‘diresmikan’—saya pakai tanda kutip, [karena] ini politik,” ujar Samsul, yang mengajar mata kuliah Indigenous Religions (Agama-agama Lokal) di CRCS.

Pada era pascareformasi, dengan masuknya klausul-klausul HAM dalam instrumen legal negara, para penganut kepercayaan kembali mendapat pengakuan. Dengan instrumen HAM, para penganut kepercayaan terlindungi dari pemaksaan untuk pindah ke agama “resmi”. Namun diskriminasi masih ada, yaitu dengan adanya Pasal 61 UU Adminduk 2006: identitas kepercayaan tidak dicatatkan dalam kolom agama.

Dengan peraturan semacam itu, menurut Samsul, negara telah melanggengkan ‘politik rekognisi’. “[Maksud politik rekognisi itu] agama dipakai untuk membedakan warga negara.”

Lebih dari itu, lanjut Samsul, “[Dengan UU Adminduk itu] negara masih melanggengkan stigma sosial terhadap penganut kepercayaan.” Stigma-stigma yang dimaksud adalah tuduhan sesat, ateis, penganut animisme, dan orang-orang belum beragama yang sah sebagai target konversi.

Mengakhiri presentasinya, Samsul merekomendasikan agar permohonan perbaikan UU Adminduk diterima. “Kepercayaan perlu dicatatkan sebagai identitas, sebagaimana kelompok agama lain… Pembedaan tersebut adalah diskriminasi.”

“Saya sadar masalah yang dihadapi kelompok penghayat ini besar, banyak sekali. Yang untuk ini saja sebenarnya saya membayangkan tidak mampu mengatasi semuanya, tetapi akan mengatasi secara signifikan sebagian besar yang dihadapi oleh penghayat kepercayaan.”

Dalam sidang, hampir semua hakim mengajukan pertanyaan. Di antara satu yang paling krusial adalah pertanyaan mengenai kompatibilitas “agama” dan “kepercayaan”. Menurut hakim yang mempertanyakan hal ini, agama perlu dipahami secara teologis dan eskatologis, bukan sosiologis, dan karena itu agama bukan sekadar persoalan administrasi.

Menanggapi pertanyaan ini, Samsul menjawab bahwa konsep agama yang teologis itu pun bukan tak mengalami konstruksi politik, dan karena itu tak bisa dilepaskan dari konteks sejarah kemunculannya sebagai diskursus. “Agama, yang merupakan terjemahan literal dari religion,” ungkap Samsul, “dipahami dengan menjiplak konsep religion di Eropa.” Para intelektual Eropa menjadikan Kristen sebagai prototype untuk menilai apakah praktik-praktik yang mereka temui di wilayah kolonial layak disebut religion atau tidak. Model konstruksi agama di Barat yang didasarkan pada (teologi) Kristen dijiplak di Indonesia, tetapi prototype-nya adalah (teologi) Islam.

“Jika definisi agama di Eropa dulu adalah untuk menegaskan superioritas Barat atas non-Barat, definisi agama di Indonesia adalah untuk menegaskan politik rekognisi: mengistimewakan kelompok warga negara tertentu dan sekaligus mendiskriminasi kelompok warga negara lain, seperti penghayat kepercayaan,” demikian Samsul menjawab pertanyaan hakim. [CRCS/aaf]

Last week Ian Wilson wrote in a New Mandala article—subsequently republished at the Jakarta Post and a number of other English Language publications, as well as being translated into Bahasa Indonesia by Tirto—about issues of inequality and poverty that didn’t feature prominently in discourses surrounding Jakarta’s gubernatorial election, either in local or international mainstream media.

The critical content of Wilson’s article was largely aimed at the campaigns of both sides in the second round of the election. I agree with the main goal of the article, namely to oppose the dominant narratives in the Jakarta election, which have been framed in binary terms (‘diversity vs. sectarian populism’), and express the issues of inequality and poverty that are of paramount importance and therefore ought to be a priority of political programs. But my agreement is accompanied by two corrections and one additional note.

Allow me to quote one sentence that summarises the article’s content and forms its main thesis. Wilson says:

Abstract

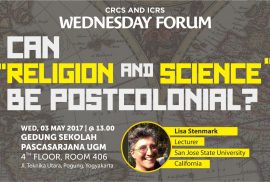

In the late-15th to mid-16th century, Europe experienced three revolutions: a geographical revolution (“voyages of discovery” and colonial expansion); a religious revolution (the Protestant Reformation) and a Scientific Revolution. Within the religion and science discourse, the relationship between two of these revolutions—the Protestant Reformation and the Scientific Revolution—has been much studied, while the third revolution has been ignored. As a result, the ghosts of colonialism still haunt us. This presentation will explore the ways considerations of the third revolution—and postcolonial perspectives—broaden out understanding and expand the discourse, with special attention to the contributions of postcolonial Science Fictions.

Speaker

Lisa Stenmark is author of Religion, Science and Democracy: A Disputational Friendship, and co-editor (with Whitney Bauman) of Religion, Science and Queer Theory, part of a series Religion and Science as a Critical Discourse. She teaches at San Jose University and, in her spare time, she practices Aikido (in which she has a Black Belt) and other martial arts, trains triathlons and is an avid Science Fiction fan.

Look at the full poster of the event here.

Anthon Jason | CRCS | Report

A tourist is half a pilgrim, if a pilgrim is half a tourist. (Turner and Turner, 1978:20)

There is an old man who is preoccupied with his rosary, praying devoutly in silence. There is also a family putting flowers on the altar and picking up holy water after doing a particular ritual. The shady trees, and the warm, soft sunlight pass through the leaves. There is silence in the air, people with calm expressions. All of these components give space for a peaceful and serene feeling, filling up the atmosphere around the place. On the other side of the park, a devout middle-aged couple is praying in small voices in front of the big cross with the high tower of a mosque visible in the background creates a unique religious nuance. This was the scene we encountered at Gua Maria at Ambarawa on our field visit to observe the intersection of religion and tourism.

On Sunday, April 9th, 2017, as part of our course on Religion and Tourism at CRCS, we visited two sites, Gua Maria in Ambarawa and Makam Sunan Pandanaran in Klaten. This field trip was important in the sense that CRCS has committed to always being up-to-date on the actual reality of religious phenomenon in Indonesia. By doing so, CRCS as an educational establishment was never meant to be an ivory tower of knowledge, but to contribute to the good of society in real life. The field trip was also an important method for comparing what we have learned in the class to the direct experience we observed in everyday life.

Led by our lecturer Dr. Kelli Swazey, and M. Rizal Abdi, a student from the CRCS 2015 batch who is currently doing research on one of the sites, we got many insights how tourism, religion, and even politics are intertwined with the tourism industry. At the two tourism sites we visited, we could not only see how the theory we learned in class fit with the phenomena that we saw at the sites, but it also showed us that the validity of the theories we have studies can be challenged in the context of the tourism sites that we visited.

Led by our lecturer Dr. Kelli Swazey, and M. Rizal Abdi, a student from the CRCS 2015 batch who is currently doing research on one of the sites, we got many insights how tourism, religion, and even politics are intertwined with the tourism industry. At the two tourism sites we visited, we could not only see how the theory we learned in class fit with the phenomena that we saw at the sites, but it also showed us that the validity of the theories we have studies can be challenged in the context of the tourism sites that we visited.

Before undertaking our field visits, we had a short lesson on how to do participant observation as a method of social research. Participant observation is defined as a method in which a researcher takes part in the daily activities, rituals, interactions, and events of a group of people as one of the means of learning the explicit and tacit aspects of their life routines and culture. The main goal of participant observation is that we attempt to observe, try and see patterns, and figure out what we can say from those observations, without imposing a particular framework.

At our first destination, the Gua Maria at Ambarawa, most of the space in the parking area was filled with private cars, and I noticed there were only a few tourist buses there. From our observation, we noted that the visitors who come to Goa Maria Ambarawa are quite varied in terms of ethnic identity. There is a family with around ten members we met enjoying their time in the garden. They had traveled from Maluku and were staying in Salatiga where one of the family members was studying at the local university. We also met a Chinese family of four doing a ritual and praying in front of the Maria statue. Not all the visitors came with their own cars, as we also spoke to a woman who had reached the site by public transportation. She sharing her experience about partaking of the holy water from the Goa Maria with us.

Another interesting point that we understood from our observation was that visitors came to the Gua Maria to obtain a kind of sanctified ‘holy’ water that flowed from faucets installed in the cave. We learned that when the site was newly inaugurated, the statue and the wellspring in Gua Maria Ambarawa was blessed with holy water from Lourdes. This was the most compelling evidence that from the beginning, the Gua Maria Ambarawa was trying to imitate the sacredness of the Marian Grotto in Lourdes. The similarity of the Mary statue between this two places has also demonstrated this. This is mentioned in the site’s official website: “Nampak sekali bahwa Gua Maria Kerep Ambarawa sejak semula diusahakan agar bisa meniru kesakralan Gua Maria di Lourdes. Hal ini tampak pada kemiripan patung Perawan Maria di Lourdes” (It is apparent that Gua Maria Kerep Ambarawa was since its beginning built to imitate the sacredness of the Marian Grotto in Lourdes as evidenced by the similarity of the Mary statue in both sites).

These phenomena display what we have learned in class about the four meanings of authenticity from Edward M. Bruner (1994). For whatever reason people visit these kinds of sites, either for tourism or pilgrimage, both can be seen as quests for an authentic experience. Dealing with this premise, the authority of the Gua Maria site as a religious space relies on a sense of ‘authentic reproduction,’ as explained by Bruner in his definitions of four types of authenticity. In this case, the site is authentic in that it is is credible and convincing. Additionally, it also fulfills Bruner’s fourth definition of authenticity related to authority or a matter of power (1994:399-400). The Catholic church, in this case, has the authority to authenticate Gua Maria to become a religious site for believers.

At the second destination on our field trip, Makam Sunan Pandanaran, we had to pass a crowded traditional market and climb a number of stairs to reach the site. For those who are not in fit condition, climbing the stairs to reach the site could be hard. At the gate, we have to abandon our footwear to enter the site, just like when we are entering a mosque. Barefoot, we entered the site to find it was well-preserved. There are many small tombs spread around the site. Somehow, I felt a similar atmosphere to when one enters Hindu or Buddhist temples. Visitors to Makam Sunan Pandanaran can do ‘wudhu’ before entering the site, but it was optional, not obligatory for visitors.

Most of the visitors at Makam Sunan Pandanaran arrive by bus, and come in large groups to the site. From the transportation used to reach the site, we can assume there is a difference in social class with these visitors than those we saw at Gua Maria. Generally speaking, we could see the social class of the visitors was rather different with the visitors of Makam Sunan Pandanaran. It is interesting to note that for some visitors, the journey to Makam Sunan Pandanaran was considered as an alternative pilgrimage for those who cannot afford to go on the required Islamic pilgrimage or Hajj in Mecca. Thus, we could see many tourism buses coming from rural areas around Java with the phrase ‘wisata religi’ on the banner clinging to the front of their buses.

Our experience at the Makam Pandaranan provided a new perspective in seeing the relationship between tourism and religion in Indonesia. Although we did not find any explicit rules about behavior or the kinds of visitors to expect at the site on the tomb’s website or any other advertisement, due to our experience we realized that there were some implicit assumptions at play in people’s behavior around the site. Tourist sites should by nature be visitors. However, when we arrived at the makam, it seemed that the site actually meant for a Muslim visitor. It is not explicitly stated, but we assumed that by observing the behavior from the people around the site.

One of the most obvious examples of this implicit rule was when our lecturer was not allowed by one of the tour guides from an outside tour agency to enter the central tomb area of Makam Sunan Pandanaran. We assumed that it was because our lecturer is a ‘bule’ with white skin and blonde hair and not using hijab, that her presence would decrease the sacred value of the space, in his perspective. In class, we have learned that exclusion is one strategy to protect and increase the sacred value of a place. This incident was valuable data in the eyes of a researcher. From this incident, we could see the paradox in ‘wisata religi’, when exclusionary tactics are applied in a tourism site. Moreover, it becomes a comprehensive example of what Justine Digance (2003) defines as ‘Contested sites’. Digance describes ‘Contested sites’ as “sacred locations where there is contest over access and usage by any number of groups or individuals who have an interest in being able to freely enter and move around the site” (2003: 144).

Another kind of contestation could be observed within the ranks of the visitors themselves. Although most of the visitors were Muslim, the religious practices they were performing at the site varied. There were some groups that recited tahlil, and other groups recited shalawat. The space within the central building of the site felt not only crowded with people, but also full of voices of praying that seemed to be competing with one another. This phenomenon demonstrates what Simon Coleman’s 2002 article criticizes about the theory of communitas in pilgrimage argued by Victor Turner. The Turneruan definition of communitas in anthropological usage claims that people at pilgrimage sites are equal, or that they share a spirit of community. In this theory, each member of the community shares a common experience, usually through a rite of passage. This phenomenon shows us the theoretical overlap between the communitas and ‘contestation’ paradigms.

One last point that emerged from our discussion in class after the field visits is that the general situation in Indonesia, where there is tension between and within religious believers, has the potential to influence the tourism industry and tourist behavior. As religious studies scholars, we are challenged to investigate the connection between religion and the other systems, such as tourism industry; as well as how religion intersects with politics, capitalism, and so on. Through the experience of this field trip and the discussion in the class, we are trained to be more alert to these connections.

*The writer Anthon Jason is CRCS student of the 2016 batch.

A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Liputan

“Tidak banyak orang yang berpikir bahwa ada ‘Islam Tuhan’ dan ada ‘Islam manusia’. Kebanyakan orang selama ini berpikir bahwa Islam itu, ya, hanya Islamnya Tuhan.” Demikian ungkap Dr. Haidar Bagir di awal peluncuran buku terbarunya yang berjudul Islam Tuhan Islam Manusia: Agama dan Spiritualitas di Zaman Kacau (Mizan, 2017) pada Jumat, 7 April 2017. Acara bedah buku ini diadakan oleh Laboratorium Studi al-Quran dan Hadis (LSQH) di Convention Hall UIN Sunan Kalijaga.

Membuka diskusi, Dr. Haidar Bagir menjelaskan dua dari sekian alasan yang membuatnya memilih judul bagi karya yang menjadi penanda ulang tahunnya yang keenampuluh itu. Pertama, menurutnya, Islam yang kini dipahami oleh seluruh muslim adalah “Islamnya manusia”, bukan Islamnya Tuhan. Artinya, apa yang dipahami oleh setiap muslim saat ini sebagai Islam atau ajaran Islam adalah keislaman yang sudah melalui proses tertentu, yakni melewati saringan otak dan hati masing-masing individu, yang tentu saja tidak kosong dari beragam faktor, termasuk nafsu di dalamnya. Karenanya, ia berbeda dengan Islam yang seutuhnya dikehendaki Tuhan. Dalam hal ini, manusia hanyalah berupaya untuk memahami Islam untuk sedapat mungkin mendekati yang dimaui Tuhan.

Dengan memahami hal ini, menurut Dr. Haidar, siapapun akan sadar bahwa setiap muslim, sepintar dan sealim apa pun, tetap memiliki peluang kesalahan sekecil apa pun di dalam pehamanan keislamannya. Tidak ada seorang pun—selain Rasulullah Saw.—dari barisan umat Islam yang pemahaman keislamannya itu mutlak betul. Dalam pandangan Dr. Haidar, jika ada orang yang menganggap bahwa hanya pemahaman keislamannyalah yang mutlak benar sedangkan yang lain mutlak salah, dia telah menempatkan dirinya sebagai Tuhan atau wakil Rasulullah.

Seharusnya, lanjut Dr. Haidar, kita belajar kepada para imam mazhab seperti Imam Syafi’i atau Imam Malik yang secara sadar mengatakan bahwa pendapatnya adalah pendapat yang benar namun tetap berpeluang salah; dan pendapat yang lain salah namun tetap berpeluang benar. Dengan begitu, siapapun tak akan berupaya memonopoli kebenaran. “Sekarang enggak; kalau melawan pendapat saya, berarti melawan Tuhan!” ujar Dr. Haidar mengungkapkan kesedihannya atas sekelompok umat Islam yang kerap menuduh sesat muslim lain dari luar golongannya.

Dr. Haidar juga menjelaskan bahwa ada kemungkinan untuk muncul lebih dari satu tafsir yang sama-sama benar dalam memahami kitab suci. Ini karena adanya sudut pandang atau pendekatan yang berbeda dalam membacanya. Menjelaskan ini, Dr. Haidar menggunakan analogi piramida: “Kalau kita lihat sejajar mata, maka tampak segitiga; kalau lihat dasarnya, maka segi empat; kalau dari atas lurus, maka jadilah seperti titik.” Perbedaan pandangan ini bukanlah sebentuk kekeliruan, namun parsialitas. Menguatkan pandangannya, Dr. Haidar menyitir ucapan Rumi bahwa kebenaran itu laiknya cermin yang jatuh ke bumi dan pecah berkeping-keping, lalu setiap orang mengambil satu kepingannya.

Alasan kedua memilih judul tersebut adalah bahwa Islam, menurut Dr. Haidar, diturunkan untuk manusia, bukan untuk Tuhan. Agama adalah seperangkat ajaran yang diturunkan demi kebaikan manusia. Di antara cara untuk itu, Dr. Haidar menekankan, adalah dengan menginternalisasi sifat Tuhan yang secara khusus tercantum dalam ucapan basmalah: ar-Rahman dan ar-Rahim. Orang Islam yang baik adalah orang yang menghabiskan hidupnya menebar kasih sayang ke semua manusia, menjadi agen rahman-rahim. Dan adalah keanehan, jika ada orang yang mendaku membela Tuhan namun begitu bernafsu membinasakan manusia, seolah-olah semakin banyak membunuh semakin ia mendapat rida Tuhan.

Di tengah-tengah diskusi, Dr. Haidar mengutarakan beberapa hal terkait isi buku setebal 288 halaman itu. Di antara yang sempat ditekankannya ialah tentang sejarah perang Nabi. Karena ada banyak narasi peperangan tertulis dalam literatur sirah Nabi, beberapa orang mengira bahwa perang adalah bagian esensial dari agama Islam. Padahal, jika dijumlah hari-hari yang digunakan Nabi untuk berperang, paling hanya dua tahun lebih sedikit saja dari total 23 tahun kerasulan beliau. “Bahkan,” lanjut Dr. Haidar, “ada penelitian yang minimalis, yang tidak memasukkan sariyyah, sehingga jika dijumlah perangnya Nabi hanya delapan puluh hari saja.” (Catatan redaksi: Dalam terminologi literatur sirah Nabi, sariyyah adalah ekspedisi pasukan tanpa dipimpin dan tak didampingi Nabi; ini yang membedakannya dari ghazwah yang dipimpin langsung oleh Nabi.)

Jika diajarkan dengan benar, Islam sebetulnya adalah agama yang menekankan perdamaian dan cinta kasih, bukan agama peperangan dan kebencian. Menegaskan hal ini, Dr. Haidar mengutip Imam Ja’far Shadiq yang secara retoris pernah berucap, “Hal al-din illa al-hubb?” (Apalagi agama itu kalau bukan cinta?) Sejalan dengan ini ialah sabda Nabi, “Cinta adalah asas(agama)ku” (al-hubb asasi). Kalau ada perintah mempersiapkan diri untuk berperang, seperti ditemukan dalam QS al-Anfal [8]:60, menurut Dr. Haidar, itu adalah tindakan preventif menghadapi serangan kelompok lain, dan bukan ditujukan untuk tindakan ofensif.

Hal lain yang juga sempat ditekankan Dr. Haidar dalam diskusi buku ini adalah tentang istilah yang populer dipakai untuk menyebut non-muslim, yaitu “kafir”. Dr. Haidar lugas menuturkan bahwa tidak seluruh non-muslim dapat dikategorikan kafir. Non-muslim yang dapat dikategorikan kafir hanyalah non-muslim yang telah menerima dakwah Islam dan telah sangat jelas memahaminya sebagai suatu kebenaran tetapi dengan sadar memilih untuk mengingkarinya karena vested interest atau alasan lain. Hal ini berdasar pada argumen-argumen dari nash al-Quran, hadis, dan pendapat para ulama lampau yang lebih detail dijelaskan di buku itu. “Untuk menyatakan non-muslim sebagai kafir itu harus ada qiyamul-hujjah,” ungkap Dr. Haidar, “Kalau Islam yang sampai kepada mereka tidak cukup meyakinkan mereka, itu berarti hujjah belum tegak, dan karena itu bukan kafir.” Dengan ini, ia mewanti-wanti agar kita tidak mudah mengobral tuduhan sesat dan kafir kepada orang yang berbeda mazhab atau beda keyakinan.

Menutup ceramahnya, Dr. Haidar menawarkan bahwa Islam paling baik diajarkan dengan memberikan penekanan pada aspek spiritualitas. Baginya, tasawuflah yang mewadahi aspek cinta dalam Islam. “Banyak umat Islam lupa kalau Islam bukan hanya terdiri dari rukun Islam dan rukun iman. Ada rukun yang merupakan puncak keimanan dan keislaman, yaitu rukun ihsan, yang ada dalam tasawuf. Ihsan inilah yang melahirkan cinta. Hilangnya ihsan membuat keislaman seseorang menjadi kering dan penuh kebencian,” pungkas Dr. Haidar.

Penulis, A.S. Sudjatna, adalah mahasiswa CRCS angkatan 2015.