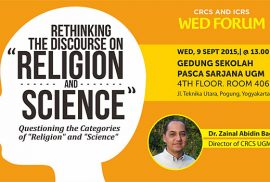

Perdebatan tentang sains, agama, dan tradisi merupakan pergulatan yang sangat panjang dalam sejarah peradaban manusia. Upaya merefleksikan dan memosisikan diri menjadi bagian penting dalam memahami makna dan hakikat pengetahuan bagi kehidupan manusia.

News

Kemunculan kredit pada film bukanlah sebuah akhir, melainkan sebuah ajakan bagi kita, yang ada di seberang layar, untuk menyambung apa yang film itu perjuangkan.

Narasi sejarah sering menghilangkan peran perempuan, kaum trans, dan masyarakat adat. Padahal, mereka berkontribusi besar dalam perjuangan sosial, budaya, dan kemanusiaan.

Industri, korporasi, bahkan lembaga negara berlomba-lomba membingkai diri sebagai bagian dari gerakan hijau. Seolah, dengan menyebut sesuatu yang hijau, seluruh proses di baliknya otomatis menjadi ekologis nan lestari.

Segregasi antara kerja akademik dan aktivisme seringkali digambarkan terpisah oleh garis batas yang saling mengelakkan. Kerja akademik dianggap harus objektif dan netral, sementara aktivisme bersifat subjektif dan politis. Karakteristik yang berlawanan itu membuat anggapan keduanya mesti dipisahkan dalam ruang lingkupnya masing-masing. Anggapan ini coba dikritisi oleh para alumni CRCS UGM berdasar kiprah mereka dalam dunia aktivisme dari berbagai latar belakang.

Program Studi Agama Lintas Budaya, Sekolah Pascasarjana, Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) menorehkan prestasi internasional dengan meraih akreditasi dari Foundation for International Business Administration Accreditation (FIBAA) pada level tertinggi: Premium Quality Seal.

Kendati berbeda cara, tiap doa dari masing-masing pemuka agama bertujuan sama: pemulihan bangsa Indonesia dari konflik berkepanjangan serta harapan akan kondisi yang lebih baik lagi. Selama prosesi tersebut, massa aksi duduk tenang seraya mengindahkan tiap untaian doa. Agama dengan caranya sendiri tengah mengadvokasi berbagai isu yang terjadi di masyarakat.

When faith meets extraction, what or whose priority comes first: communities, organizations, or the environment?

Fellowship KBB 2025 kali ini menghadirkan kelas Klinik dan Advokasi KBB sebagai bagian dari luaran yang tidak hanya menghasilkan gagasan tertulis, tetapi juga aksi nyata.

Melindungi KBB bukan hanya soal agama atau keyakinan, melainkan juga memastikan semua orang, terutama kelompok rentan, dapat hidup dan berkembang tanpa diskriminasi.

Jauh sebelum “religion” diperkenalkan kolonialis Eropa, masyarakat Nusantara telah memiliki pengertian “agama” dengan mengikuti konsep dīn.

Cara masyarakat Dondong menghidupi tradisi merefleksikan sebuah relasi yang erat antara manusia dan alam. Melalui pengetahuan lokal yang terwariskan secara temurun, semua entitas saling terhubung di dalam telaga dondong, mulai dari tanah, akar, air, manusia, hingga hewan. Masing-masing memiliki peran untuk saling bersinergi.

Selama ini KUHP 2023 yang akan efektif berlaku tahun depan ini jarang dibicarakan di akar rumput. Padahal, masyarakat awamlah—terutama dari kelompok rentan keagamaan—yang akan terpengaruh secara signifikan.

Karakter dari KUHP itu adalah membatasi hak. Yang menjadi perhatian ialah bagaimana pembatasan itu tidak melanggar hak warganegara, terutama dalam hal beragama atau berkeyakinan.

Meski diwanti-wanti sebagai kemajuan setengah jalan, KUHP 2023 menjanjikan terbuka luasnya ruang tafsir untuk melindungi hak beragama dan berkeyakinan.

Sebagai daerah khusus yang memiliki hukum tersendiri, integrasi KUHP 2023 dan qanun diperlukan untuk menjaga kebebasan beragama atau berkeyakinan (KBB) di Aceh.

Betapa pun berbeda pengalaman dan pandangan religius dengan generasi pendahulunya, anak muda Khonghucu tak akan pernah tercerabut dari “tulang” leluhurnya.

Transpuan dan Hak Demokrasi yang Terabaikan

Nita Amriani – 11 November 2024

Apakah seorang transpuan lahir hanya untuk mengecap pedihnya bayang-bayang persekusi dan menjadi pelengkap suara pemilu?

Diskriminasi dan stigma berlapis menyingkirkan kelompok transpuan dari hak-hak dasar sebagai warga negara. Banyak transpuan sulit mengakses pekerjaan dan hidup dalam ancaman persekusi. Di sisi lain, mereka juga tak lagi punya ruang aman di rumah karena keluarga mereka tidak lagi mau menerimanya. Bagi kelompok transpuan, konsep keadilan dalam sila ke-5 Pancasila masih jauh api dari panggang.

Suara Masyarakat Adat di Tengah Bayang-Bayang Demokrasi

Vikry Reinaldo Paais – 06 November 2024

Pembangunan nasional yang diklaim oleh pejabat pemerintahan sebagai sarana untuk meningkatkan kesejahteraan sosial justru merampas, mengkriminalisasi, serta mengeksklusi hak-hak hidup masyarakat adat dan penganut agama leluhur. Hutan dan tanah mereka dirampas oleh negara untuk dijadikan kawasan produksi maupun konservasi. Ketika masyarakat adat berjuang mempertahankan hak atas tanahnya, mereka justru dikriminalisasi oleh aparat negara. Dalam konteks sosio-religius, sebagian besar masyarakat maupun pemimpin agama menstigma masyarakat adat sebagai belum beradab, masih primitif, serta belum beragama sehingga harus dimodernkan dan diagamakan. Problematika ini adalah tantangan serius dalam konteks Indonesia yang mengumandangkan demokrasi sebagai sistem pemerintahan dan prinsip hidup berbangsa dan bernegara. Isu-isu krusial ini menjadi bahasan utama dalam perhelatan International Conference and Consolidation on Indigenous Religion (ICIR) ke-6 pada 22-25 Oktober 2024 di Ambon.

Transformasi Modernitas yang Berlantas di Kanekes

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 15 Oktober 2024

Modernitas membawa tantangan bagi masyarakat Urang Kanekes. Namun, mereka punya cara tersendiri dalam menghadapinya.

Masyarakat adat Urang Kanekes—atau yang lebih populer dengan nama Baduy—di Banten selalu menarik perhatian para peneliti. Setidaknya ada 95 dokumen karya ilmiah yang memuat kata kunci “Baduy” dan 23 dokumen karya ilmiah dengan kata kunci “Kanekes” di situs Scopus. Ketertarikan ini muncul, di antaranya, karena masyarakat adat Kanekes sangat melestarikan ajaran tradisi leluhur sampai hari ini kendati wilayah adat mereka tidak jauh dari Jakarta, kota metropolitan serba modern.

Kedai kopi yang dianggap sekadar tempat transaksi ekonomi, ternyata menjadi ruang penting terciptanya sebuah dinamika relasi lintas etnis dan agama yang sarat akan luka masa lalu.

Keberagaman di Tengah Keberagamaan

Yohanes Leonardus Krismawan Anugrah Putra – 30 September 2024

“…because we believe the Indonesian voices need to be projected and amplified not just in Indonesia, but beyond as well”

Demikian sepenggal sambutan Brett G. Scharfis, Direktur International Center for Law and Religion Studies (ICRLS) dari Univeritas Brigham Young, dalam study visit bertajuk “Promoting Freedom of Religion or Belief in Indonesia: Challenges and Opportunities” di auditorium Pascasarjana UGM. Kunjungan belajar ini bukan sekadar visitasi institusional, melainkan juga ruang untuk membicarakan berbagai peluang maupun tantangan dalam membangun kebebasan beragama atau berkeyakinan (KBB) di Indonesia.

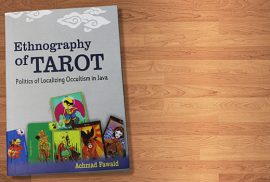

Ambiguitas dan Toleransi dalam Tradisi Masyarakat Muslim

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 25 September 2024

Sepanjang sejarah peradaban Islam, perdebatan tafsir selalu hadir dengan saling menghargai perbedaan pendapat.

Realitas pemahaman dan praktik ajaran Islam sebagai aturan universal masih ambigu. Meski tuntunannya termaktub dalam pegangan dasar—Al-Qur’an dan hadis—interpretasinya selalu terbuka untuk dibahas dari perspektif dan ideologi tertentu. Cendekiawan dan ulama kerap berbeda paham atas interpretasi ajaran Islam sehingga mendorong terbentuknya ragam tafsir dan tarekat dalam Islam.

Dari Nurani Jadi Aksi

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 15 September 2024

Sebagian umat beragama menyadari gejala alam yang tidak menentu sebagai fenomena perubahan iklim. Lantas, sejauh mana pengetahuan agama mendorong umatnya melakukan kegiatan yang mendukung lingkungan?

“Agama memiliki efek ganda dalam membentuk perilaku ramah lingkungan,” jelas Iin Halimatusa’diyah, Direktur Riset Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat (PPIM) UIN Jakarta, lewat presentasinya bertajuk “From Belief to Action: Religious Values and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Indonesia” dalam Wednesday Forum (4/9).

Tanda-tanda kerusakan lingkungan ini sudah mulai terlihat. Erosi semakin sering terjadi, hasil panen menurun, dan banyak petani mulai bangkrut. Dalam situasi genting ini, alih-alih mengambil langkah konservasi lahan pertanian, para petani kentang terus memacu produksi kentang seolah tidak terjadi apa-apa. Masjid-masjid besar yang menjadi simbol kesejahteraan terus bermunculan, aktivitas keagamaan pun kian inten

berdasarkan data dari Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC), Bima merupakan daerah dengan rekam jejak aktivitas terorisme yang tinggi. Lantas, karakteristik keagamaan seperti apa yang tengah berkembang di antara masyarakat Bima? Sejauh mana karakteristik keagamaan itu mempengaruhi perkembangan terorisme di Bima?

Meneroka Diplomasi Buddhis dalam Sejarah Asia Modern

Yulianti – 20 Agustus 2024

Dalam sejarah kolonialisme di Asia modern, jejaring dan aliansi tidak hanya terjadi melalui jaringan negara kolonial, tetapi juga aliansi kelompok masyarakat yang ada di dalamnya. Salah satu bentuk aliansi yang berperan penting dalam geopolitik tersebut ialah diplomasi buddhis.

Dinamika tersebut menjadi bahasan utama dalam panel “Friends in Dharma: Buddhist Diplomacy and Transregional Connection in Modern Asia”. Panel ini merupakan bagian dari kluster tema Inter Area/Border Crossing pada “AAS in ASIA Conference”di Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia pada 9–11 Juli 2024. Mengambil latar belakang sejarah Asia modern, panel Buddhist Diplomacy ini memfokuskan kajian pada kiprah komunitas agama yang berasal dari kalangan yang berbeda-beda dalam membentuk jaringan, aliansi, dan kerja sama di Asia pada pertengahan abad ke-20 sampai ke-21. Jaringan dan hubungan-hubungan kelompok inilah yang kemudian dimaknai sebagai buddhist diplomacy (diplomasi buddhis) yang melibatkan individu, kelompok, dan negara-negara buddhis di Asia. Keberadaan diplomasi buddhis ini mempengaruhi hubungan transregional dan pertukaran budaya dari abad ke-20 hingga abad ke-21 di Asia.

Hijrah Minim Sampah:

Sebuah Ekolinguistik Islam ala Ibu Rumah Tangga

Nanda Tsani – 29 Juli 2024

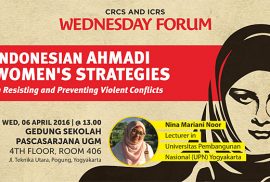

Isu lingkungan tidak melulu berkutat pada hal-hal gigantis seperti krisis iklim, efek rumah kaca, kenaikan suhu bumi, mencairnya es Antartika, atau kepunahan massal. Bagi June Cahyaningtyas, isu lingkungan ialah juga tentang hal-hal keseharian yang tampak di pelupuk mata dan jangkauan tangan: wastafel mengilap yang kembali dipenuhi piring kotor, ember kosong yang penuh pakaian apek, hingga timbunan sisa makanan di tempat sampah dapur. Berangkat dari minat keamanan nontradisional dalam kajian Hubungan Internasional (HI), dosen HI Universitas Pembangunan Nasional “Veteran” ini meneroka dimensi keagamaan dalam praktik lingkungan berkelanjutan melalui pengalaman perempuan urban di Jawa. Hasil kajiannya itu ia presentasikan dalam Wednesday Forum, 15 Mei 2024, bertajuk “Sustainable Living Practice Among Urban Women in Java”.

Beradaptasi lewat Agama di Tengah Abrasi Pantai Utara Jawa

Rezza Prasetyo Setiawan – 20 Juli 2024

Salah satu dampak nyata krisis iklim ialah kenaikan air laut dan abrasi yang menenggelamkan daerah-daerah di kawasan garis pantai. Sebagai negara dengan garis pantai terpanjang di dunia, Indonesia menjadi salah satu wilayah yang paling terdampak. Lantas, bagaimana masyarakat Indonesia yang tinggal di kawasan terdampak beradaptasi dengan hal ini? Sejauh mana pemahaman dan praktik keagamaan mereka berperan dalam proses adaptasi tersebut?

Pertanyaan itu menjadi salah satu titik tolak disertasi Aliyuna Prastiti yang ia presentasikan dalam Wednesday Forum bertajuk “Making Sense of Religion in Adaptation Processes”, 8 Mei 2024. Dosen program studi Hubungan Internasional, Universitas Padjadjaran, ini meneliti dua komunitas masyarakat yang tinggal pesisir utara Pulau Jawa, yaitu Bedono, Kabupaten Demak, Jawa Tengah dan Pantai Bahagia, Bekasi, Jawa Barat.

Mempertahankan Agama Seadanya–Sebisanya di Negara Transit

Nanda Tsani – 16 Mei 2024

Pernahkah Anda transit di suatu bandara luar negeri? Transit selama 2 atau 3 jam mungkin tidak begitu terasa sembari menikmati fasilitas yang ada, tetapi bagaimana jika harus transit hingga puluhan jam? Betapapun berbagai aktivitas membunuh waktu dilakukan, tetap saja jemu itu datang, bukan? Sementara, para pengungsi dan pencari suaka di Indonesia rerata menjalani waktu transit antara 5 sampai 10 tahun penuh kegetiran.

Berangkat dari situasi yang dialami para pencari suaka ini, Realisa D. Massardi, Dosen Antropologi UGM, melakukan penelitian etnografi guna memahami manuver dan dinamika para remaja pengungsi dan pencari suaka dalam menavigasikan identitas keagamaan mereka di tanah transit. Selama kurang lebih 14 bulan dalam kurun 2016–2017, Dosen Antropologi UGM ini melakukan penelitian di empat lokasi pengungsian. Realisa memaparkan hasil penelitiannya dalam Wednesday Forum edisi 24 April 2024 bertajuk “Religion in Transit: Young Refugees Navigating Religious Sphere in Indonesia”.

Kendati lebih dari 90% responden di Indonesia mengatakan bahwa agama merupakan faktor penting bagi kebahagiaan mereka, agama bukanlah jawaban utama ketika mereka mengalami gangguan kesehatan mental.

Ketika terdesak oleh bencana yang sudah lugas di depan mata, masihkah faktor identitas sosial, politik, dan keagamaan menjadi penting? Apakah pertanyaan itu tidak lagi penting karena perbedaan sudah dilebur demi alasan kemanusiaan dan penderitaan bersama? Jangan-jangan, hilangnya pertanyaan itu justru adalah tanda marginalisasi terselubung yang justru makin tajam karena desakan keterbatasan sumber daya?

Agama dan spiritualitas seolah menjadi dua entitas yang berbeda. Di tengah zaman yang kian berpacu dan berkelindan, dinamika interaksi keduanya menjadi kunci untuk memahami hubungan antaragama di masa depan.

Pengalaman transendental nun di atas langit seringkali tidak bisa kita gapai dengan intelektual. Di sinilah humor bekerja. Dengan humor, agama yang adiluhung nan surgawi bisa menjadi sangat manusiawi dan membumi.

Memulihkan Literasi Agama-Agama Tionghoa

Rezza Maulana – 12 Januari 2024

By breadth of reading and the ties of courtesy, a gentleman is kept, too, from false paths (Confucius)

Eksistensi dan kiprah masyarakat keturunan Tionghoa dalam derap sejarah Nusantara seakan tenggelam oleh stigma negatif yang menyelimutinya. Padahal, dinamika pemikiran dan pergulatan mereka ikut menyumbang batu bata dalam bangunan negeri yang bernama Indonesia ini. Salah satu penyebabnya ialah minimnya kajian yang bersumber dari sudut pandang masyarakat keturunan Tionghoa itu sendiri. Kebijakan asimilasi, represi, dan aksi amuk massa yang kerap menyasar komunitas keturunan Tionghoa ikut menyumbang hilangnya berbagai dokumen penting dan sumber sejarah. Untungnya, di samping koleksi pribadi atau perorangan, beberapa arsip sejarah yang tersimpan di klenteng atau rumah ibadah masih terselamatkan.

Menuntut Keadilan Lingkungan Antargenerasi Melalui Konstitusionalisme Iklim

Rezza P. Setiawan – 8 November 2023

Hak Asasi Manusia tidak hanya dimiliki oleh generasi manusia yang hidup di hari ini, tetapi juga generasi yang akan datang. Salah satunya akses terhadap lingkungan hidup yang baik dan sehat.

Istilah ‘konstitusionalisme iklim’ (Climate Constitutionalism) dibawa oleh Dr. Herlambang Perdana Wiratraman dalam diskusi pleno ketiga pada acara The 6th International Conference for Human Rights yang diadakan (26/10) di Fisipol UGM. Dalam presentasi berjudul “Climate Constitutionalism: A Search for Eco Social Justice in Indonesia’s Autocratic Legalism”, Dosen Hukum Tata Negara UGM ini menjabarkan konstitusionalisme iklim sebagai kerangka untuk memahami secara kritis hubungan tidak terpisahkan antara iklim dan hukum. Singkatnya, kerangka pikir ini menelisik apakah sistem hukum yang ada berpihak pada perusakan atau restorasi lingkungan. Konstitusionalisme iklim ini juga menjadi jembatan hukum untuk pemenuhan hak asasi manusia Indonesia, baik generasi saat ini maupun yang akan datang, atas lingkungan hidup. Lebih lanjut, Wiratraman juga menyoroti secara kritis narasi “politik hijau” yang ditawarkan kapitalisme global sebagai ancaman terhadap pemenuhan hak asasi antargenerasi.

Melawan Perdagangan Orang, Agama Bisa Apa?

Rezza P. Setiawan – 30 Oktober 2023

Realitas perbudakan nyatanya tidak pernah sungguh-sungguh kita tinggalkan. Pakaian, sepatu, laptop, ataupun gawai yang kita gunakan untuk membaca artikel ini boleh jadi hasil dari perbudakan yang tidak (ingin) kita sadari. Kerja paksa itu tidak hanya ada di zaman kolonial, tetapi juga di era milenial. Ia berganti rupa dalam bentuk perdagangan orang. Para sindikat perdagangan orang mencari korban di daerah asal dengan iming-iming gaji besar. Para korban kemudian dibawa ke negara lain dan diperkerjakan tanpa legalitas yang jelas. Akibatnya, mereka tidak bisa menuntut haknya sebagai manusia, apalagi sebagai pekerja. Tak jarang dari para korban itu pulang hanya tinggal nama dan jasadnya. Data BP2MI menunjukkan setidaknya ada 1.900 jenazah WNI yang dipulangkan sebagai korban Tindak Pindana Perdagangan Orang (TPPO).

Fellowship KBB 2023: Merajut Kolaborasi untuk Advokasi

Hanny Nadhirah – 30 Oktober 2023

“Kebebasan Beragama atau Berkeyakinan adalah ilmu (dan upaya) yang tiada habisnya. Harapannya, teman-teman bisa terlibat dalam gerakan ini,” ungkap Asfinawati, advokat hak asasi manusia dan pengajar di Sekolah Tinggi Hukum Indonesia Jentera yang menjadi fasilitator program Fellowship Kebebasan Beragama atau Berkeyakinan (KBB) 2023.

Sejak diinisiasi pada 2019, Fellowship KBB merupakan wadah bagi para dosen lintas studi untuk mengembangkan pengajaran dan penelitian mengenai KBB. Program kolaborasi CRCS UGM; Yayasan Lembaga Bantuan Hukum Indonesia; Centre for Human Rights, Multiculturalism and Migration, Universitas Jember; Serikat Pengajar Hak Asasi Manusia (Sepaham); dan Sekolah Tinggi Hukum Indonesia Jentera ini melibatkan para akademisi dan praktisi sebagai fasilitator. Dalam fellowship ini para peserta mengeksplorasi berbagai dimensi isu KBB melalui beragam studi kasus di Indonesia secara lintas disiplin.

Sehari bersama Ari Gordon: Mengenal Yahudi dan Yudaisme

Vikry Reinaldo Paais – 25 Mei 2023

Apa itu Yahudi (Jewish), apa itu Yudaisme (Judaism), apa itu Israel? Masih banyak orang awam, bahkan akademisi, yang salah kaprah terhadap istilah-istilah tersebut. Yahudi cenderung diasosiasikan dengan sebuah agama sekaligus suku bangsa, bahkan negara dalam konteks modern. Secara terminologi, ketiga istilah tersebut memiliki makna yang berbeda. Yahudi merujuk pada suku, etnis, atau kelompok masyarakat; sedangkan Yudaisme adalah nama agama yang dipeluk oleh mayoritas orang Yahudi. Sementara, Israel adalah nama negara di kawasan Timur Tengah yang mendeklarasikan kemerdekaannya pada 14 Mei 1949 dan memiliki penduduk dengan suku yang beragam (tidak hanya dari etnis Yahudi, tetapi juga Arab, Druze, hingga suku-suku dari Afrika) dan agama yang bermacam pula (Yudaisme 73,6%, Islam 18,1%, Kristen 1,9%, dll.).

Salah satu isu mendasar yang penting untuk diklarifikasi mengenai KBB adalah bahwa yang dilindungi oleh KBB adalah manusia sebagai subjek hak, bukan agama.

Sasi Haruku: Ruang Sanding dan Tanding Antara Adat dan Gereja

Haris Fatwa Dinal Maula – 14 Juni 2022

Pengetahuan adat sering kali disisihkan ketika berhadapan dengan isu-isu kontemporer. Stigma primitif, tertinggal, dan animis menjadi tembok besar sehingga pengetahuan adat seakan-akan tidak relevan dan terpinggirkan. Namun, tesis itu tidak sepenuhnya benar. Masyarakat Negeri Haruku, Kepulauan Lease, Maluku Tengah telah membuktikannya. Berkat praktik sasi yang telah turun-temurun mereka lakukan, masyarakat Haruku mendapat penghargaan nasional Kalpataru kategori penyelamat lingkungan pada 1985.

Salah satu kunci penting dalam mencegah kerusakan alam dan mewujudkan keadilan sosial justru bertumpu pada sosok yang paling kerap disisihkan: perempuan adat.

Di tengah kondisi bumi yang darurat ini, pengetahuan adat bisa menjadi antitesis dari agrikultur modern yang bersifat merusak. Agama leluhur memainkan peran sentral di dalamnya.

The course will combine lectures from multidisciplinary professors of Universitas Gadjah Mada, cultural practices and exchanges between Japanese and Indonesian university students using both English and Japanese. The short course is a collaboration between Tsukuba University, CRCS, Graduate School-UGM, and the Faculty of Cultural Science, UGM.

This 3rd conference invites researchers, academics, CSO activists, practitioners, and community members to share ideas, insights, knowledge, experience, and wisdom on issues relative to access to justice.

Meskipun kunjungan lapangan (fieldtrip) ke berbagai tempat dan komunitas yang multikultur dari waktu ke waktu semakin populer dipakai di kelas-kelas pendidikan formal di kampus, sayangnya belum ada panduan akademik yang memadai. Panduan ini berusaha mengisi kekosongan itu.

Dibandingkan disiplin keilmuan lain, studi agama memang datang agak “terlambat“ dalam menanggapi isu lingkungan. Di sisi lain, para sarjana studi agama seringkali berfokus pada hubungan interpersonal seperti hubungan antara umat Islam dan Kristen, ekstremisme dan fundamentalisme, dan sebagainya. Perspektif hubungan harmonis antara kita dan alam seolah-olah terpinggirkan. Lantas, seberapa penting agama dan ekologi untuk dikaji dalam studi agama?

Peluncuran Buku Varieties of Religion and Ecology in Indonesia

Wacana mengenai agama dan ekologi/lingkungan dewasa ini makin berkembang pesat di dunia, termasuk di Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (CRCS) UGM. Selain menawarkan mata kuliah Religion and Ecology selama beberapa tahun terakhir, tidak sedikit mahasiswa CRCS UGM menulis tesisnya dalam bidang ini. Beberapa ringkasan tesis yang terbit dalam beberapa tahun terakhir kini diterbitkan dalam buku Varieties of Religion and Ecology: Dispatches from Indonesia. Buku tersebut disunting oleh Zainal A. Bagir, Michael S. Northcott, dan Frans Wijsen.

Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (CRCS), Sekolah Pascasarjana Universitas Gadjah Mada; Yayasan Lembaga Bantuan Hukum Indonesia; Centre for Human Rights, Multiculturalism and Migration—Universitas Jember, dan Serikat Pengajar Hak Asasi Manusia (Sepaham) menyelenggarakan Program Fellowship Kebebasan Beragama atau Berkeyakinan (KBB) untuk Angkatan Ketiga pada tahun 2021.

Program ini bermisi membangun basis pengetahuan akademik bagi KBB dan memberikan landasan yang lebih kokoh untuk advokasi KBB. Tujuan utama program ini adalah meningkatkan riset-riset multidisiplin mengenai KBB, dan diadakannya pengajaran mengenai KBB (baik sebagai mata kuliah tersendiri atau bagian dari mata kuliah) di perguruan tinggi, dalam disiplin hukum, syariah, filsafat, studi agama, dan ilmu-ilmu sosial dan politik.

CRCS’ Admission 2021 Extended

Admission to the Center for Religious and Cross-Cultural Studies (CRCS) in the 2021/2022 academic year has been extended until 6 July. CRCS’ tuition-free scholarship is still available!

For more information click Admission 2021 and for scholarship

CRCS welcomes graduate students and the public to enroll in the three intersession courses on religious and cross-cultural studies for credit or as auditors.

Dialog sebagai modus perjumpaan antargama dan etika global sebagai tanggung jawab agama-agama dalam merambah masalah sosial, ekonomi, dan politik inilah dua dari sekian buah pikiran yang ditinggalkan Hans Küng.

Buku ini menghimpun esai-esai foto yang memotret praktik ekologi adat komunitas Ammatoa yang mengejawantah dalam kehidupan sehari-hari termasuk berbagai ritual, seni dan tradisi, serta berbagai aturan adat.

An open recruitment for Public Education division at CRCS UGM

Kamis, 4 Februari 20212. DIselenggarakan atas kerja sama Indonesian Pluralities (CRCS UGM, Pardee School of Global Studies - Boston University, dan Watchdoc) dan Yayasan Cahaya Guru.

Online screening and discussion of the third film of the Indonesian Pluralities series, Oct 14, 2020

Acara hari Kamis 12 Maret di Fisipol UGM. Terbuka untuk umum dan gratis.

Peluncuran film kedua seri Indonesian Pluralities di IAIN Ambon, Rabu, 29 Jan 2020, bekerja sama dengan Ambon Reconciliation & Mediation Center (ARMC).

Peluncuran "Beta Mau Jumpa", film kedua seri Indonesian Pluralities, di IAKN Ambon, Selasa, 28 Januari 2020, bekerja sama dengan Pusat Studi antar-Budaya dan Agama (PSaBA), IAKN Ambon.

Selasa, 10 Desember 2019, di Universitas Paramadina. Memperingati hari Hak Asasi Manusia.

Peluncuran dan diskusi film pertama dari seri Indonesian Pluralities, di Goethe-Institut, Jakarta, 30 Nov 2019.

Peluncuran dan diskusi film pertama dari seri Indonesian Pluralities, di Pasar sepaHAM, Fisipol UGM, 23 Nov 2019.

Intersession courses: Religion and Human Rights; and Comparative Mysticism: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Foto-foto dari Pekan Budaya Tionghoa Yogyakarta (PBTY) di kampung pecinan Ketandan, pada 13-19 Februari 2019.

Pemutaran dan Diskusi Film "Our Land is the Sea", 10 Oktober 2018.

Liputan dari kegiatan KKN PPM UGM dan CaRED UGM di Organda, Jayapura.

CRCS welcomes graduate students and the public to enroll in our 2018 intersession courses.

A prayer recited in conclusion of UGM's "Act of Concern Confronting Terrorism" event held at Balairung UGM on 14 May 2018.

Konferensi Pendidikan Agama Inklusif III di Universitas Kristen Duta Wacana, Yogyakarta, pada 8 Mei 2018.

Diskusi buku "Islam dan Kebebasan", bersama Kaprodi CRCS Dr Zainal Abidin Bagir, pada Jumat, 27 April 2018.

CRCS UGM menyelenggarakan lokakarya tentang masyarakat sadar ekowisata bersama masyarakat adat Ammaota serta Dispar dan DLHK Kabupaten Bulukumba, Sulawesi Selatan.

In commemoration of the World Water Day 2018, CRCS UGM presents these free, open-to-the-public events.

Dosen dan alumnus CRCS UGM menjadi saksi ahli dalam uji materi UU Penodaan Agama di Mahkamah Konstitusi, 20 Februari 2018.

Wednesday Forum, December 6, 2017. Speaker: Rudolf Dethu, founder of Muda Berbuat Bertanggung Jawab.

Wednesday Forum, 29 Nov 2017. Speaker: Farsijana Adeney-Risakotta, grantee of the Contending Modernities project.

Wednesday Forum, 22 November 2017. Speaker: Wening Udasmoro, the dean of the Faculty of Cultural Sciences, UGM.

CRCS, Kampung Halaman dan Satunama menyelenggarakan pemutaran film dan diskusi buku pada Kamis, 16 Nov 2017, pukul 13.00.

Wednesday Forum, 15 November 2017. Speaker: Mark Woodward, Associate Professor at Arizona State University.

Mahkamah Konstitusi: Pengosongan Kolom Agama bagi Penghayat Kepercayaan Bertentangan dengan UUD 1945

MK mengabulkan permohonan uji materi terkait aturan pengosongan kolom agama bagi penghayat kepercayaan di KK dan KTP.

Wednesday Forum, 8 November, 2017. Speaker: Prof. Dr. Hans-Peter Grosshans from Germany.

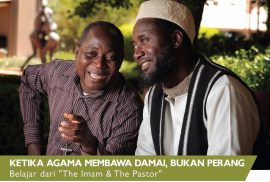

A report of the first day of the workshop on the institutionalization of interfaith mediation with Imam Ashafa and Pastor Wuye at UGM.

Liputan dari hari ketiga bersama Jacky Manuputty dalam rangkaian kuliah umum "Imam & Pastor" dan lokakarya Pelembagaan Mediasi Antariman.

Liputan acara kuliah umum bersama Imam Ashafa dan Pastor Wuye dari Nigeria di Gadjah Mada University Club, 10 Oktober 2017.

Wednesday Forum, Nov 1, 2017. Speaker: Evi Sutrisno, PhD candidate in Anthropology at the University of Washington.

Wednesday Forum report of the presentation by Maria "Deng" Giguiento, a peacebuilding activist and trainer at Mindanao Peacebuilding Institute.

Wednesday Forum, October 25, 2017. Speaker: Prof. Bernard Adeney-Risakotta, the founding director of ICRS, Yogyakarta.

Wednesday Forum, October 18, 2017. Speaker: Prof. Gerrit Singgih from Duta Wacana Christian University, Yogyakarta.

A report of Mun'im Sirry's presentation on Islamic christology at the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on September 27, 2017.

Wednesday Forum, Oct 11, 2017, with Maria (Deng) Gigiento from the Philippines.

Kuliah umum bersama Imam Muhammad Ashafa dan Pastor James Wuye di Gadjah Mada University Club, 10 Oktober 2017, pukul 18.30-21.00 WIB.

Wednesday Forum, October 4, 2017, with Linda Yanti Sulistiawati from the Faculty of Law, UGM.

A student's reflection on the Talentime movie watched in the CRCS's Religion and Film course.

CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum, Sept 27, 2017, with Dr Mun'im Sirry of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

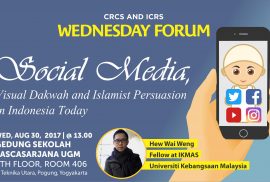

A report on Dr Hew Wai Weng's presentation at the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum, August 30, on the dakwah style of Chinese-Indonesia Felix Siauw.

Mengkaji agama-agama secara interreligius tidak bertujuan untuk mencari persamaan esensial dari semua agama, tetapi untuk memahami suatu agama dari perspektif agama itu sendiri.

Wednesday Forum, September 20, learning experiences of Mitra Wacana. Speaker: Arif Sugeng Widodo.

Pengumumaan 15 peserta SPK Tingkat Lanjut di Yogyakarta 2-8 Oktober 2017.

Tentang macam-macam kelompok Muslim di Myanmar, isu kewarganegaraan, konflik etnoreligius, dan munculnya gerakan ekstrem yang makin menajamkan perseteruan Buddhis-Muslim. Bacaan pengantar dari Prof. Imtiyaz Yusuf.

This presentation will argue for the need for a paradigm shift in the understanding of Islam from a religion oriented to law (nomos) to one oriented to love (eros), from prioritizing orthodoxy to orthopraxy.

Bagaimana hubungan agama dan kekerasan dalam tragedi Rohingya? Refleksi mahasiswa dari matakuliah Religion, Violence and Peacebuiliding di CRCS.

Setelah kasus "penodaan agama" mantan gubernur Jakarta, persekusi banyak terjadi di daerah. Tulisan ini membahas kasus dokter Otto Rajasa di Balikpapan.

CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum, Sept 6, 2017. Speaker: Dr. Mohammad Iqbal Ahnaf.

"Pelaksanaan syariat Islam" mendapat payung dari undang-undang, yang memanifes dalam qanun-qanun, dan telah menjadi wacana hegemonik di Aceh. Bagaimana advokasi toleransi beragama dapat dilakukan dalam konteks demikian?

CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum, August 30, 2017, at the Graduate School, Universitas Gadjah Mada, on the dakwah method of a young Hizbut Tahrir-affiliated preacher.

Berbagai kebijakan mengenai masyarakat, sejak masa kolonial hingga kini, telah kerap berubah. Namun pertanyaan utamanya tetap sama: sudahkah masyarakat adat berdaulat?

Wednesday Forum on August 23, 2017, discussing the relationship between Indonesia's New Order government and Muslim groups. The speaker: Gde Dwitya Arief Metera from Northwestern University.

After being dissolved, members of Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia have choices to be ideologically consistent or to make compromise. Each has its own consequences.

The fraught election of a new leader for Jakarta has triggered reactions from regions across Indonesia and influenced the dynamics of local identity politics. As will be discussed in this essay, adat organizations promoting local identity as grounded in ethnic customs, in Minahasa, a Christian majority region of North Sulawesi, have gained momentum from controversies in Jakarta to reassert their existence by protesting against organizations they identify as intolerant towards Indonesian pluralism. Specifically, they have turned their attention to those groups pushing the position that, as a Christian, former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaha Purnama (known as Ahok), was not permitted (according to one reading of the Quran) to serve as the governor of a majority Muslim province.

Setelah dibubarkan, anggota Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia memiliki dua pilihan: tetap bersikukuh dengan prinsip ideologinya atau berkompromi dengan realitas politik. Masing-masing punya konsekuensi.

Selamat kepada mahasiswa baru CRCS UGM TA 2017/2018.

The overly optimistic view regarding the prospects for Indonesia's religious democracy needs to be qualified.

Empat tautan bacaan tentang HTI, Pancasila, dan isu terkait di situsweb CRCS.

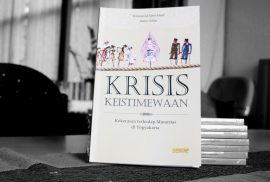

Review buku Krisis Keistimewaan: Kekerasan terhadap Minoritas di Yogyakarta (CRCS 2017)

Konservatisme tak perlu menjadi sumber kecemasan. Isu yang lebih penting bersifat sangat praktis: bagaimana negara, khususnya aparat penegak hukum, mampu menjaga ruang deliberasi yang aman.

CALL FOR APPLICATIONS. The Institutionalization of Interfaith Mediation: A Workshop with Imam Muhammad Ashafa & Pastor James Wuye. Deadline: July 15, 2017.

Hadirnya kelompok-kelompok radikal-intoleran yang kerap melakukan kekerasan atas nama agama adalah suatu tantangan iman. Dalam menghadapi kelompok ini, umat beriman semestinya tidak membalasnya dengan kekerasan yang serupa, tetapi harus dengan cara-cara yang selayaknya dilakukan orang beriman, yakni cara yang penuh kasih dan kelembutan.

Itulah di antara yang diungkapkan Kardinal Julius Darmaatmadja, SJ, dalam seminar nasional bertajuk Merajut Persaudaraan, Mengikis Sikap Intoleran yang dihelat di Fakultas Teologi Universitas Sanata Dharma pada 16 Mei 2017. “Yang paling membuat tantangan iman semakin besar di dalam diri kita adalah kalau yang menjadi marah besar itu kita sendiri. Itu tantangan iman untuk diri kita sendiri,” ungkapnya

The secularists must learn to accommodate religion in the public sphere while the religious leaders must help balance the public role of religion with spirituality.

Beasiswa bebas SPP di CRCS untuk alumni perguruan tinggi non-Islam.

“Gereja-gereja memahami perdamaian secara sempit, sekadar sebagai negative peace. Perdamaian dianggap tercapai apabila tidak ada konflik.”

Sebagai salah satu pusat iman Kekristenan, Kenaikan Yesus selaiknya menjadi momen refleksi. Salah satunya tentang pesan Yesus sebelum naik meninggalkan para murid-Nya.

Pada hari Senin, 22 Mei 2017, Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) mengumandangkan deklarasi meneguhkan kembali Pancasila. Termasuk dalam rangkaian acara adalah sarasehan dan FGD bersama akademisi dan budayawan.

The government’s reason in its move to disband Hizbut Tahir Indonesia, claimed to have an ideology that contradicts Pancasila, should remind us of the “Pancasila as the sole foundation” politics of the authoritarian New Order regime.

Pilkada Jakarta berimbas pada dinamika politik lokal berbasis identitas dari ormas-ormas adat-Kristen di Tanah Minahasa.

Perayaan Waisak adalah salah satu hari besar umat Buddha untuk memperingati tiga peristiwa: hari lahir Sidharta Gotama (calon Buddha Gautama), momen Sidharta mendapatkan pencerahan ilmu, dan hari mangkatnya Buddha. Ketiga peristiwa ini terjadi pada bulan Waisak saat purnama.

Waisak dirayakan dalam berbagai bentuk dengan skala yang beragam. Denyut perayaan Waisak tidak hanya terasa di negara-negara berpenduduk mayoritas Buddha seperti Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, atau wilayah mainland Asia Tenggara lain. Negara-negara di mana agama Buddha tidak dipeluk mayoritas penduduknya seperti Indonesia pun menggemakan Waisak melalui acara-acara besar.

Sharing her experience as a German woman converting to Islam, Dr Katrin Bandel gave a presentation at the Wednesday Forum.

Anna M. Maćkowiak, a doctoral student from Jagiellonian University presented her research in Wednesday Forum about how Islam has been perceived in her home country, Poland.

Abstract

The architectural form is one indicator that reflects religious practices evolve over long periods of time. There are scholars who do not accept that religions and religious architecture have a history. These scholars prefer to believe that religious practices emerge fully formed and that they are static (i.e. they do not change). Most scholars, however, view the practice of religion as an evolving phenomenon based upon cultural symbolism. Furthermore, religious practices can be influenced by contact with external groups and often reflect shared histories between different religions. This is an idea that is frequently in conflict with political sensitivities, but may also offer opportunities for inter-faith dialogue.

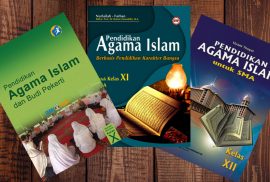

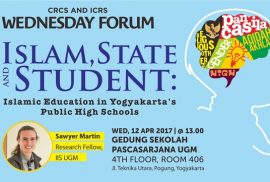

At the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on April 12th, 2107, Sawyer Martin French, a research fellow at the Institute for International Studies at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Universitas Gadjah Mada, gave presentation on the government-mandated curricula of Islamic education in public high schools. He took several public high schools (Sekolah Menengah Atas, SMA) in the province of Yogyakarta, with the method of classroom observation, interviews with teachers, and student focus group discussions in a few schools. More importantly, he also presented his research on Islamic textbooks used in those high schools which he observed have undergone content changes.

In his presentation, French showed that each political period has a difference in the emphasis of the contents of the Islamic textbooks used in SMA. There are three political periods where curricula for Islamic education in SMA have evolved, from the 1994 curriculum, which was formed under the Suharto New Order’s regime; then replaced by the 2006 curriculum under the post-reformation period; and the latest, 2013 curriculum. French shows the content of the Islamic curricula has undergone several changes, three main of which are that related to tolerance, democracy and gender issues.

Dalam aturan perundang-undangan, para penghayat kepercayaan atau penduduk yang agamanya “belum diakui” diminta untuk tidak mengisi kolom agama dalam Kartu Tanda Penduduk (KTP), “tetapi tetap dilayani dan dicatat dalam database kependudukan”.

Namun pada kenyataannya di lapangan, para penghayat kepercayaan yang mengosongkan kolom agama di KTP tidak mendapatkaan pelayanan yang setara sebagaimana warga negara pada umumnya, bahkan mengalami diskriminasi.

Last week Ian Wilson wrote in a New Mandala article—subsequently republished at the Jakarta Post and a number of other English Language publications, as well as being translated into Bahasa Indonesia by Tirto—about issues of inequality and poverty that didn’t feature prominently in discourses surrounding Jakarta’s gubernatorial election, either in local or international mainstream media.

The critical content of Wilson’s article was largely aimed at the campaigns of both sides in the second round of the election. I agree with the main goal of the article, namely to oppose the dominant narratives in the Jakarta election, which have been framed in binary terms (‘diversity vs. sectarian populism’), and express the issues of inequality and poverty that are of paramount importance and therefore ought to be a priority of political programs. But my agreement is accompanied by two corrections and one additional note.

Allow me to quote one sentence that summarises the article’s content and forms its main thesis. Wilson says:

While the campaigns present, at one level of analysis, a stark contrast between ‘diversity’ on the one hand and sectarian populism on the other, a shared point of commonality is the respective silence regarding a significant shaping force in Jakarta, and arguably the election: rising levels of economic inequality.

Abstract

In the late-15th to mid-16th century, Europe experienced three revolutions: a geographical revolution (“voyages of discovery” and colonial expansion); a religious revolution (the Protestant Reformation) and a Scientific Revolution. Within the religion and science discourse, the relationship between two of these revolutions—the Protestant Reformation and the Scientific Revolution—has been much studied, while the third revolution has been ignored. As a result, the ghosts of colonialism still haunt us. This presentation will explore the ways considerations of the third revolution—and postcolonial perspectives—broaden out understanding and expand the discourse, with special attention to the contributions of postcolonial Science Fictions.

A tourist is half a pilgrim, if a pilgrim is half a tourist. (Turner and Turner, 1978:20)

There is an old man who is preoccupied with his rosary, praying devoutly in silence. There is also a family putting flowers on the altar and picking up holy water after doing a particular ritual. The shady trees, and the warm, soft sunlight pass through the leaves. There is silence in the air, people with calm expressions. All of these components give space for a peaceful and serene feeling, filling up the atmosphere around the place. On the other side of the park, a devout middle-aged couple is praying in small voices in front of the big cross with the high tower of a mosque visible in the background creates a unique religious nuance. This was the scene we encountered at Gua Maria at Ambarawa on our field visit to observe the intersection of religion and tourism.

“Tidak banyak orang yang berpikir bahwa ada ‘Islam Tuhan’ dan ada ‘Islam manusia’. Kebanyakan orang selama ini berpikir bahwa Islam itu, ya, hanya Islamnya Tuhan.” Demikian ungkap Dr. Haidar Bagir di awal peluncuran buku terbarunya yang berjudul Islam Tuhan Islam Manusia: Agama dan Spiritualitas di Zaman Kacau (Mizan, 2017) pada Jumat, 7 April 2017. Acara bedah buku ini diadakan oleh Laboratorium Studi al-Quran dan Hadis (LSQH) di Convention Hall UIN Sunan Kalijaga

“Terpujilah Engkau, Tuhanku, karena Saudari kami, Ibu Pertiwi, yang menyuapi dan mengasuh kami, dan menumbuhkan aneka ragam buah-buahan, beserta bunga warna-warni dan rumput-rumputan. Saudari ini sekarang menjerit karena kerusakan yang telah kita timpakan kepadanya, karena tanpa tanggung jawab kita menggunakan dan menyalahgunakan kekayaan yang telah diletakkan Allah di dalamnya.”

Begitulah Paus Fransiskus memulai bait-bait awal ensiklik keduanya. Didahului dengan ucapan “Laudato Si’, mi’ Signore,” “Terpujilah Engkau, Tuhanku,” yang ia kutip dari ucapan Santo Fransiskus dari Asisi, pendahulunya ratusan tahun lalu, Paus Fransiskus memulai penegasan sikapnya yang lahir dari refleksi keimanan atas realitas dunia yang hadir saat ini. Dua ratus empat puluh enam paragraf dari keseluruhan ensiklik ini berbicara soal bagaimana seharusnya manusia beragama dan beriman bersikap atas alam dan lingkungannya.

Abstract

Positionality is an important issue in the humanities and social sciences today. What is the relationship of the researcher to the topic she/he is discussing? From what position does she/he speak? To me personally as European living and working in Indonesia, this has always been challenging question. It has become even more complex and challenging since I converted to Islam. Only one essay in my newest book (2016) is explicitly about this, but basically the book is written from the perspective of someone in the process of crossing over (converting) and reflects on the ambivalence of this process.

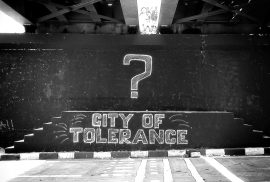

Yogyakarta telah lama menjadi rumah yang aman bagi berbagai tradisi, keyakinan, dan paham pemikiran yang beragam. Tetapi Daerah Istimewa ini belakangan disorot karena banyaknya aksi vigilantisme yang dilakukan sejumlah kelompok massa baik yang berlatar belakang agama atau politik. Aksi-aksi vigilantisme yang menyasar kelompok-kelompok sosial dan keagamaan minoritas menimbulkan pertanyaan apakah Yogyakarta, yang dikenal sebagai kota pendidikan dan pusat kebudayaan Jawa yang menekankan pada harmoni sosial, sudah berubah menjadi daerah yang intoleran? Laporan ini menunjukkan bahwa vigilantisme terhadap minoritas tidak cukup secara sederhana dipahami sebagai ekspresi konservatisme keagamaan dan intoleransi para pelaku terhadap minoritas, tetapi juga merupakan bagian dari proses perubahan sosial dan struktural yang diantaranya dipengaruhi oleh dinamika seputar status keistimewaan Yogyakarta. Tidak bisa dipungkiri, sektarianisme yang menguat belakangan ikut berpengaruh, tetapi seringkali kekerasan terhadap minoritas lebih tampak sebagai alat mobilisasi kelompok-kelompok kepentingan tertentu untuk mempertahankan basis sosial-politik yang menentukan kendali mereka atas ruang dan sumber daya.

_________________________

Abstract

The EU countries have been inefficiently managing the latest European migrant crisis, among them Poland was particularly unsuccessful. Contemporary discourse on refugees from the Middle East in Poland revolves around the following issues: the danger of altering Polish culture, the increase of the likelihood of terrorism, and the postulate of empathy towards people threatened by war. The religious factor plays a significant role in this discourse, since refugees who come from predominantly Muslim countries from a group of special interest in this Catholic-majority state. Halina Grzymała-Moszczyńska, Adam Anczyk, and Anna M. Maćkowiak have examined, qualitatively, how Poles perceive Islam, and how this image may be associated with attitudes towards refugees. The aim of this study was to analyze narratives about Islam and the religious Other, emerging from partially structured interviews. The questionnaire, containing citations from the Bible, the Quran, and the Bhagavad Gita served as the trigger for interviews conducted after filling it out.

In Indonesia, people can be called by their homeland’s name, such as orang Batak, orang Sunda, orang Manado and so on. The Indonesian concepts that are tied tightly to ideas of land, community, and cosmology referred to as adat have a dynamic and complex relationship to people’s religious identification and how they understand their identities. People can be emplaced or displaced in regard to how their religious identity relates to their cultural identification with particular places. While emplacement is the process by which people identify themselves with a place, displacement is a dislocation, removal, expropriation, takeover, or ideological process to refute claims of rights over land, the use of cultural symbols, or the ability of people and groups to self-identify.

Indonesia is home to many environmental movements, either led by established environmental activists or by groups of indigenous people. The reclamation project in Benoa Bay, cement mining in Kendeng area, Central Java, and the Save Aru movement are just a few recent examples. Does religion play a role in these movements? Are these local movements related to the growing global environmental movement?

The local and global is a crucial element of environmental movements, because environmental problems defy boundaries. Our rapidly-changing climate poses an urgent challenge that is both global and local. As national governments slowly acknowledge their role in reducing carbon emissions (with some exceptions), local communities in Indonesia are living with the problems of rising temperatures and sea levels, increases in natural disasters, and increasing pollution of our air and water.

Local-global connections in religious environmental movements

In 2016 at the climate summit in Morocco, governments met to affirm their adoption of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Signed by 111 countries (as of November 2016), the agreement commits to reducing carbon emissions and recognizes the human impact on climate change. At the same climate summit in Marrakech, hundreds of religious leaders and environmental activists launched the Interfaith Climate Statement.

The Interfaith Climate Statement included these words:

Throughout history, our religious traditions have provided support and inspiration during times of great challenge or transformation. We must commit to new ways of living that honor the dynamic relationships between all forms of life to deepen awareness and the spiritual dimension of our lives. We must draw on courage, hope, wisdom and spiritual reflection to enable our young and future generations to inherit a more caring and sustainable world.

Abstract

One of the most significant ways the Indonesian state plays an active role in the country’s religious life is through education: Muslim students at all levels are required to take Islamic education classes, for which the government writes curricula and employs teachers. Therefore, the state—from the center at the Ministry of Religious Affairs to the periphery at individual teacher at public schools—has considerable power to shape religious perspectives of each new generation. His ongoing research is an ethnographic study of Islamic education in public high schools (Sekolah Menengah Atas Negeri) in the province of Yogyakarta, carried out through classroom observation, teacher interviews, and student focus groups. He will present the characteristics and effects of Islamic education in three fields: (a) perspective of religious diversity within Islam; (b) the valorization of the democratic nation-state as Islamic; and (c) the gender ideologies promoted as normatively Islamic. It is also noted how these phenomena vary in and among schools, noting the influence of socio-economic class, education, gender and religious background.

As a product of the globalized world, social media have created a virtual space of communication and interaction. Many people use it with enthusiasm as it helps humans build communication and connectivity much faster than ever before. On the other hand, many consider this phenomenon a challenge for living ethically and productively.

Dealing with this topic, Wednesday Forum on February 9th 2017 held a discussion on “wefies” (group self-portraits posted on social media) in relation to the Islamic concept of riya’ (showing off piety). The two speakers, Fatimah Husein, currently teaching at CRCS/ICRS as well as UIN Sunan Kalijaga, and Martin Slama of the Institute for Social Anthropology at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, presented the emerging phenomenon of online piety in Indonesia, especially on how Muslims rethink riya’ in today’s popular “wefie” culture. The presentation was based on Husein’s article titled “The Revival of Riya’: Displaying Muslim Piety Online in Indonesia” which has been submitted for a virtual issue of American Ethnologist and Slama’s research project on “Islamic (Inter)Faces of the Internet: Emerging Socialities and Forms of Piety in Indonesia” funded by the Austrian Science Fund.

Fatimah Husein and Martin Slama observed that media are central to the articulation of Indonesian Muslims’ pious life. They further gave examples of online communities such as ODOJ (One Day One Juz) and wefies practices among Muslims during religious rituals, traveling, or pengajian (religious gathering). This phenomenon, they argued, requires Muslims to deal with the riya’ question, because during the last two decades showing off one’s Islamic piety mediated by smartphones and the Internet has become widespread.

The United States and Indonesia are both plural societies that struggle to understand how to live together in diversity and with the meaning of pluralism itself. From its beginnings seventeen years ago, CRCS has had strong ties with American academia. Pioneers in inter-religious studies from the U.S., including John Raines, Mahmud Ayoub and Paul Knitter, were present at our founding and have been followed by a number of visiting lecturers who have stayed for a few weeks, months, or years, and by generations of English teachers. In addition, more than thirty CRCS alumni/ae have continued their studies for MA and PhD degrees in American universities. As we followed the news of the U.S. election within the context of the anti-pluralist turns across Asia and Europe, we wanted to know what our American friends are thinking and so we invited them to contribute their reflections to this page. This article, written by Laine Berman, is the second of the Voices from America series. To read the Indonesian translation of this article, click here

Abstract

In post-conflict Maluku, there has been renewed interest in redeveloping the Banda Islands as a major tourist attraction for the region, and as a world heritage site. As practices of tourism represent culture for diverse audiences, they also inform how local inhabitants conceptualize their identities, as well as influence the processes of collective memory. The Indonesian concepts of culture draw on relationships to land, community and cosmology referred to as adat that have a dynamic and complex relationship to people’s religious identifications. In this talk, I’ll explore how Christians displaced from the Banda islands during the conflict are being “re-membered” as outsiders in the process of reconstructing culture for the consumption of tourists, and consider how representations of culture for the tourism industry can potentially strengthen exclusive versions of local identity.

Universitas Gadjah Mada’s Faculty of Biology invited Whitney Bauman to present his on-going project at the Biology Hall on Monday, March 6th, 2017. Students and lecturers from various faculties came to hear his lecture. His specialization on the discourse of religion, science, and nature reflects his capacity as an associate professor at the Department of Religious Studies, Florida International University, as well as author of works including Theology, Creation, and Environmental Ethics (Routledge 2009) and Religion and Ecology: Developing a Planetary Ethics (2014). A longtime friend of CRCS who has taught intersession courses more than once, he is currently working to finish his third, single-authored book with a tentative title Truth, Beauty and Goodness: Ernst Haeckel and Religious Naturalism.

Abstract

As suggested by Ben Anderson, media is a powerful means in creating imagined community and accordingly in establishing a sense of cosmopolitanism. Taking this insight, the presentation will explore the rethoric represented in the series of comic under the title Baladeva, published by Tantraz Comiks (/Comics) Bali, Denpasar. The comic will be framed within the notion of micro-cosmopolitanism—a cosmopolitanism from below (Cronin, 2006)—through which the pressing questions of imagination of nationalism and cosmopolitanism, counter-transnational religious discourse, and religious minority are played out. Contemplating the present day contestation between nationalism and transnationalism discourse, understanding contemporary comics to a degree might illuminate the shift in the present Indonesia, notably from the perspective of popular culture.

The United States and Indonesia are both plural societies that struggle to understand how to live together in diversity and with the meaning of pluralism itself. From its beginnings seventeen years ago, CRCS has had strong ties with American academia. Pioneers in inter-religious studies from the U.S., including John Raines, Mahmud Ayoub and Paul Knitter, were present at our founding and have been followed by a number of visiting lecturers who have stayed for a few weeks, months, or years, and by generations of English teachers. In addition, more than thirty CRCS alumni/ae have continued their studies for MA and PhD degrees in American universities. As we followed the news of the U.S. election within the context of the anti-pluralist turns across Asia and Europe, we wanted to know what our American friends are thinking and so we invited them to contribute their reflections to this page. This is the first of the Voices from America series. To read the Indonesian translation of this article, click here

Abstract

The presenters examine popular forms of online piety in Indonesia. They are particularly concerned how Indonesian Muslims try to cope with the ambivalences that their social media practices inevitably generate. These practices range from taking wefies (selfies of a group of people) at religious events that are posted on social media platforms, participating in online Quran reading groups, various form of online da’wah (proselytization) to documenting one’s pilgrimages and meetings with Islamic figures online. Given the importance of visibility that these social media practices entail, the presentation has a special focus on the concept of riya’ (showing off one’s piety) reminding Muslims to avoid that behavior. Arguing that discussions about riya’ have experienced a kind of revival in today’s social media age, the presenters attempt to point out that online piety is inherently ambiguous eliciting a dynamic of discourses and practices that considerably informs the current field of Islam in Indonesia today.

Abstract

Since 2011, 5 million Syrians have fled civil war in their country. Most of these refugees live in local communities in neighboring countries. Local faith communities and global humanitarian actors regularly work together to provide assistance for Syrian refugees. This talk presents research about Arab and Western Christians providing support for Syrian refugees living in Jordan, based on fieldwork conducted in 2015-16. The talk addresses three questions raised in literature about faith-based organizations working in humanitarian and development projects: 1) Do religious groups approach aid differently from non-religious (secular) organizations?; 2) What is the role of local faith communities in providing humanitarian aid?; 3) How do religious groups providing aid manage religious difference and deal with challenges of proselytization?

Agar tak salah arah, kebijakan seharusnya berdasar pada riset. Kesenjangan antara kebijakan dengan pengetahuan acapkali berujung pada kebijakan yang tak menyelesaikan masalah. Termasuk di sini kebijakan yang berkenaan dengan umat beragama.

Untuk menjembatani pemerintah dengan akademisi, pada 14 Februari 2017 Balitbang Kementerian Agama bekerja sama dengan Pusat Studi Agama dan Demokrasi (PUSAD) Paramadina mengadakan diskusi dengan topik mengenai definisi agama dan penodaan agama sebagai rangkaian dari serial diskusi “Analisis Kebijakan: Riset dan Kebijakan Terkait Kehidupan Beragama di Indonesia”. Serial diskusi ini direncanakan akan menghasilkan buku terkait tema-tema seperti intoleransi, konflik agama, kebebasan beragama dan berkeyakinan, dan kerukunan antarumat beragama. Forum diskusi itu dihadiri berbagai kalangan dari pihak Kemenag, termasuk Menteri Agama Lukman H. Saifuddin, para akademisi dan aktivis. Dua dosen Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya (CRCS), Dr Samsul Maarif dan Dr Zainal Abidin Bagir, menjadi pembicara dalam forum itu.

Abstract

Conflict between Sunni and Shia Muslims has taken place in Madura, particularly in Sampang, for many years, triggered typically not in relation to different interpretations of the Islamic faith but rather by clashes between the various personal and political interests of the local religious elites. This study examines the opinions, beliefs, and experiences of the communities of Sunni and Shia adherents in Madura using a communication-cultural studies perspective in order to explore the contestation of meanings of local religious and ethnic identities. This perspective can provide an alternative for unpacking the everyday lives of the Sunni and Shiites and understanding the conflict through their local cultural backgrounds and religious experiences.

Sebanyak 16 peserta, yakni 8 orang dari Jayapura dan 8 orang dari Merauke, mengikuti pelatihan yang diadakan CRCS dan Ilalang Institute.

Abstract

Until 1935, the Dutch Protestant mission (zending) in Indonesia was officially run by male missionaries. Women were considered to be supplementary rather than essential actors. Despite the fact that there is only limited information available about them, women were involved in the Dutch Protestant mission from the early nineteenth century. This talk presents a study about the experience and role of Dutch women in the Protestant mission, with particular reference to the existing letters written between 1855 and 1931 by four missionary wives who lived in Sulawesi and North Sumatra. The letters of the four women reveal their domestic and social activities, as well as their perceptions of their role in the mission and the society in which they lived. This talk explores gendered notions in missionary practices and points out the lack of attention to the study of women in Christian missions within the broader framework of Indonesian colonial history.

Speaker

Maria Ingrid Nabubhoga is now a Ph.D. candidate at the Faculty of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies at Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands, in the project ‘Indonesia Mirrors’, jointly organized by Radboud University Nijmegen, The Nijmegen Institute for Mission Studies Radboud University and Duta Wacana Christian University (UKDW). Her Ph.D. project explores the perception of contemporary Indonesian immigrants on religion and modernity in the Netherlands, in continuity with the Dutch colonial past in Indonesia.

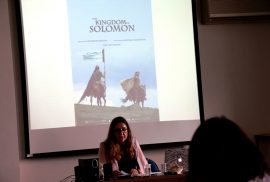

Going to the cinema is a new social practice in modern society. To some extent it can also be perceived as a spiritual practice. Dr Nacim Pak-Shiraz, the Head of Persian Studies and a Senior Lecturer in Persian and Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh and guest speaker at the Wednesday Forum on February 9th, studies this paradox in the dynamics of Iranian cinema. She began by noting that there has been only a little academic attention to the movies based on Quranic epics, in contrast to what has happened with Biblical epics from Hollywood.

For a long time, the study of the Quran has been focused on the text and its interpretation. Pak-Shiraz explained that movies lead us to cultural contexts and deeper understanding of Islamic arts. Therefore, more attention should be given to the dynamics of Quran and its representation in the creative industry.

Jonathan Zilberg, a cultural anthropologist whose research and advocacy focuses on museum ethnography, argued that Indonesian museums face such problems as performance, transparency and accountability, but they have the potential power to promote pluralism to the public. In his February 1st Wednesday forum presentation, he raised questions as to how Indonesian museums can be a strong bond to serve Indonesia’s diversity.

Based on his research in National Museum of Indonesia in Central Jakarta, Zilberg argued that museums are an extension of culture and identity. He conducted his research by closely examining the activities of visitors of National Museum. He took photos from different angles and then reflected on how visitors interact with the objects on display. He stressed that a museum that functions well should be a place to learn and display democracy. Different people come to the museum with various interests. These differences can lead them to learn about pluralism in comfortable ways.

Abstract:

Urban people are always exposed to soundscape, to sounds and noises in their everyday life. With the aid of technology, the soundscape of Yogyakarta has dramatically changed in the last 30-40 years. The sounds which once gave certain characteristics to the city have changed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For most people it does not bother them if they do not pay attention to them. However, people accept certain sounds as acceptable sounds while some other may reject them as disturbing noises. The result of such perceptions create spsychologically different responses, either positively or negatively. Therefore, exploring how people in the City of Tolerance responding to the religious soundscape of the place where they live is an effort to see an interfaith relationship from a different perspective, the auditory angle.

Speaker:

Jeanny Dhewayani, Ph.D. is the Associate Director of Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS) Yogyakarta.She got her Master degree from University of New Mexico and Ph.D. from Australian National University, both in Anthropology. Now, She is also a professor of anthropology at Duta Wacana Christian University.

Issues of environmental damage are becoming more pervasive recently. It was just a few months ago we hear the voices of Samin community, indigenous people in the slopes of Mount Kendheng advocating environmental justice against industrialization attack surrounding the mountain, the issue of which inspired Dian Adi M.R., one of CRCS students, to compose instrumental music and conceptualize arts performance at the event called “Sounds of The Indigenous”.

Through his experience in music performance, Dian initiated the event and collaborated with various musicians, environmental activists, and academia of religious and cultural studies. This innovative way of giving collaborative performance is purposively to raise an awareness among various professions to work together on preserving nature.

Agama dan negara memiliki relasi yang erat dalam kehidupan bernegara di Indonesia. Pembukaan Undang-Undang Dasar 1945 alinea ketiga menyatakan kemerdekaan Indonesia adalah “atas berkat rahmat Allah Yang Maha Kuasa.” Kalimat dalam alinea ketiga Pembukaan UUD 1945 itu adalah salah satu representasi pengakuan negara terhadap eksistensi agama, meskipun Indonesia menyatakan dirinya sebagai negara kesatuan yang mengakui keragaman melalui semboyan bhinneka tunggal ika. Indonesia merupakan suatu bangsa yang multietnis dan multireligius, dan rakyatnya memiliki multiidentitas.

Abstract

Iranian cinema is one of the very few in the Muslim world to have employed this new medium in imagining and narrating stories of religious figures. The representation of religious figures in Islam has become particularly controversial in recent years. Therefore, it turned into a highly sensitive undertaking. In this talk I examine the complex socio-political context of Iran to study late emergence of the epic genre in Iranian cinema. In doing so I study the recent creation and development of ‘Qur’anic Films’ within Iranian cinema with specific reference to Kingdom of Solomon (Mulk-i Sulayman-i Nabi, Shahriar Bahrani, 2010), which I argue is the first Qur’anic epic in Iranian cinema if not in the Muslim world.

Speaker

Dr Nacim Pak-Shiraz is the Head of Persian Studies and Senior Lecturer in Persian and Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh. She is the author of Shi’i Islam in Iranian Cinema: Religion and Spirituality in Film (London, 2011) and a number of articles and chapters in the field of Iranian Film Studies. Dr. Pak-Shiraz also regularly collaborates with a number of film festivals, including the Edinburgh International Film Festival and The Edinburgh Iranian Festival.

Bertebarannya hoax, provokasi, dan ujaran kebencian berbasis agama akhir-akhir ini merupakan fenomena yang sangat memprihatinkan. Untuk mengatasi hal ini, dengan tujuan yang berjangka panjang, pendidikan adalah hal yang tak bisa diabaikan.

Menyoroti hal itu, pada pertengahan Januari 2017, Jokowi memanggil Menag, Mendikbud, dan Menristekdikti. Sebagaimana diberitakan kemudian, menurut keterangan Menteri Agama Lukman Hakim Saifuddin, Presiden Jokowi antara lain memberikan pesan tentang pentingnya pengembangan pendidikan karakter bangsa terutama melalui pendidikan agama. Dengan bahasa lugas, Presiden berharap tiga menteri tersebut memberikan perhatian pada pengembangan pendidikan agama yang tidak konfrontatif, tapi “promotif”, yakni pendidikan yang mempromosikan religiositas dan sekaligus menghargai kebinekaan.

Dua aspek dari bangsa Indonesia menjadi pertimbangan dari upaya itu: di satu sisi, masyarakat Indonesia adalah masyarakat yang religius, atau setidaknya memiliki identitas keagamaan yang kuat; dan di sisi lain Indonesia memiliki kemajemukan agama yang sangat tinggi baik antaragama maupun intraagama. Kuatnya identitas agama di Indonesia itu diperkuat oleh hasil survei Pew Research Institute 2015 yang menyebutkan 95% orang Indonesia menyatakan agama penting bagi kehidupan mereka.

Temuan Penelitian

Penelitian tentang peran agama dan/atau pendidikan agama di sekolah dan pembentukan karakter siswa telah banyak dilakukan. CRCS UGM sendiri setidaknya telah mempublikasikan dua buku hasil penelitian dalam bidang ini.

Pertama, penelitian dengan judul Politik Ruang Publik Sekolah: Negosiasi dan Resistensi di SMUN di Yogyakarta (Hairus Salim HS, dkk, 2011). Buku ini menyajikan etnografi tiga sekolah negeri, dari yang toleran, “biasa”, dan kurang toleran terhadap kemajemukan. Penelitian ini tidak secara khusus mengkaji pendidikan agama dalam ruang kelas, tetapi tentang proses pembentukan ruang publik sekolah dan pengaruhnya terhadap relasi antar siswa.

Kedua, penelitian dengan judul Politik Pendidikan Agama: Kurikulum 2013 dan Ruang Publik Sekolah (Suhadi, dkk, 2014). Terbitan penelitian ini membahas genealogi atau asal usul pendidikan agama dalam sistem pendidikan nasional di Indonesia serta aspek politik pendidikannya dari satu rezim ke rezim lain setelah Indonesia merdeka. Penelitian ini juga mengkaji persoalan “kompetensi spiritual” dalam Kurikulum 2013.

Penelitian lain tentang pendidikan agama terkini juga telah dilakukan oleh Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat (PPIM) UIN Syarif Hidayatullah yang fokus pada content analysis buku-buku teks ajar Pendidikan Agama Islam (PAI) dari SD sampai SMA yang diterbitkan oleh Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan (Kemendikbud). Policy brief dari riset ini diterbitkan pada September 2016 dengan judul Tanggung Jawab Negara terhadap Pendidikan Agama Islam.

Latar dari penelitian tersebut adalah fenomena protes dari masyarakat di beberapa daerah yang menemukan pernyataan intoleransi dan kekerasan dalam buku-buku dan Lembar Kerja Siswa (LKS) PAI. Salah satu dari pernyataan itu, misalnya, dapat ditemukan dalam sebuah LKS PAI Kelas XI SMA di beberapa daerah sekaligus (Jombang, Depok, Jakarta, Bandung) yang memuat kalimat “yang boleh dan harus disembah hanyalah Allah SWT, dan orang yang menyembah selain Allah, telah menjadi musyrik dan boleh dibunuh.” Meskipun pernyataan itu tak mengacu secara khusus ke suatu agama, tim PPIM mengkhawatirkan pernyataan itu dalam konteks Indonesia dapat disalahpahami merujuk pada pemeluk agama tertentu di luar Islam (PPIM 2016:4)

Sebagaimana disebutkan dalam policy brief PPIM itu, setelah ditelusuri LKS tersebut ternyata menyalin secara utuh buku Pendidikan Agama Islam dan Budi Pekerti Kelas XI SMA yang dipublikasikan oleh Kemendikbud (Mustahdi dan Mustakim 2014; PPIM 2016: 4). Walhasil, sinyalemen bahwa ada potensi intoleransi dan kekerasan dalam buku teks PAI bukanlah mengada-mengada.

Ketika diwawancarai tim peneliti PPIM, pejabat Kemendikbud menyebutkan mengapa hal tersebut bisa terjadi. Menurutnya, proses penyusunan dan penerbitan buku-buku tersebut bersifat kejar tayang atau terpepet dari sisi waktu, sehingga hasilnya tidak maksimal. Namun peneliti PPIM memandang buku-buku PAI bisa dimasuki pernyataan seperti di atas karena pemerintah tidak memiliki visi menjadikan PAI sebagai bagian dari politik kebudayaan nasional atau bagian dari upaya memperkuat Islam rahmatan lil’alamin (PPIM 2016: 6).

Berpikir Lebih Mendasar

Banyak pihak telah lama menyarankan pemerintah secara serius memikirkan dan mengupayakan perbaikan PAI yang kontekstual dengan keindonesiaan dengan ragam agama, paham kegamaan, dan etniknya. Persoalan memperbaiki kurikulum PAI tidaklah semudah membalikkan tangan. Untuk hasil yang lebih maksimal ada perlu perubahan pola pikir dalam memandang pendidikan agama yang lebih mendasar.

Pertama, Pendidikan Agama (PA) secara umum, tidak terkecuali PAI, dalam sejarahnya memuat beban ideologis. Sebelum tahun 1966, Pendidikan Agama (PA) bukan mata pelajaran wajib, tetapi pilihan. Namun instruksi TAP MPRS No. XXVII/MPRS/1966 tentang Agama, Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan kemudian menetapkan PA sebagai mata pelajaran wajib bagi semua siswa. Pewajiban tersebut, pada waktu itu, berkaitan dan berhubungan dengan bias anti-komunisme. Artinya, ada aspek semangat penegasian sang liyan. Karena sentimen anti-komunisme ini dan agama yang diakui oleh perundang-undangan saat itu (masih berlaku hingga saat ini) hanya enam agama, maka pendidian agama di luar enam agama tersebut tidak pernah ditawarkan sepanjang sejarah.

Untuk konteks saat ini, hal yang penting adalah bagaimana menggeser paradigma tersebut ke arah yang lebih positif. Saya tidak sedang ingin mengusulkan kembali PA menjadi tidak wajib lagi, tetapi bagaimana keberadaannya yang wajib kini lebih memiliki semangat positif. PAI harus keluar dari perspektif negatif menuju perspektif yang lebih positif dalam melihat perbedaan agama dan paham. Tanpa perubahan paradigma yang mendasar, harapan terhadap PAI, bahkan juga pendidikan agama lain, untuk menjadi “promotif” dan tidak konfrontatif akan sulit tercapai.

Kedua, kurikulum terbaru yang berlaku saat ini, yakni Kurikulum 2013 (selanjutnya disingkat K-13), tidak lagi menjadikan Pendidikan Agama sebagai satu-satunya ruang untuk menanamkan nilai-nilai keagamaan/spiritualitas. K-13 memperkenalkan konsep Kompetensi Inti (KI) dan Kompetensi Dasar (KD). KI kemudian diturunkan ke dalam empat kompetensi: kompetensi spiritual (KI-1), kompetensi sosial (KI-2), kompetensi pengetahuan (KI-3) dan kompetensi keterampilan (KI-4). Oleh karena itu kompetensi agama/spiritual tidak lagi hanya menjadi tanggung-jawab PA, tapi semua mata pelajaran. Artinya, agenda perbaikan terhadap kurikulum dan buku teks PAI tidak niscaya menyelesaikan masalah yang diprihatinkan di atas. Maka kita sekaligus juga harus memeriksa rumusan KI-1 yang tersebar di semua mata pelajaran.

Ketiga, banyak di antara pemerhati dan praktisi pendidikan sering terjebak menyederhakan tujuan pendidikan dalam kaitannya dengan tanggung jawab mata pelajaran tertentu. Misalnya, ketika dalam UU No. 20 tahun 2003 tentang Sisdiknas disebutkan bahwa tujuan pendidikan adalah mendorong peserta didik agar menjadi “manusia yang beriman dan bertakwa kepada Tuhan Yang Maha Esa”, tujuan itu dianggap menjadi tanggung jawab mata pelajaran PA. Sementara itu tujuan pendidikan untuk mendorong “menjadi warga negara yang demokratis serta bertanggung jawab” seringkali dianggap menjadi beban Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan (PPKn). Paradigma semacam ini mengakibatkan adanya ambiguitas, yaitu PPKn mengajarkan keterbukaan sosial kebangsaan, sementara PA mengajarkan ketertutupan sosial kebangsaan.

Pemahaman ambigu tersebut seharusnya diakhiri. Mendorong lahirnya generasi bangsa yang “demokratis”, “bertanggung jawab”, “mandiri”, dan seterusnya, juga merupakan tanggung jawab pendidikan agama. Oleh karena itu, kurikulum PA seharusnya tidak saja berkutat pada keimanan dan ketakwaan, tapi juga hal-hal yang menyangkut sosial dan kebangsaan.

Perbaikan kurikulum terhadap buku teks yang konfrontatif memang menjadi agenda mendesak yang perlu segera dilakukan. Lebih dari itu, kita perlu memperbaiki hal-hal mendasar yang menyangkut paradigma dan pola pikir kita tentang pendidikan agama apabila mengharapkan pendidikan agama menjadi mata pelajaran yang lebih promotif terhadap nilai-nilai kebinekaan bangsa Indonesia.

*Penulis, Suhadi, adalah dosen Program Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga dan associate researcher di Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS), Sekolah Pascasarjana UGM.

Abstract:

In this discussion, Jonathan Zilberg will discuss problems fracing Indonesian museum in terms of performance, accountability and transparency. He will discuss the Goverment of Indonesia’s 2010-2014 museum revitalization program, the transformations that have been taking place in Indonesia museum over the last decade and the challenges posed for the future. He will look at museums as democracy machines and as postcolonial centers for advacing the ideology of pluralism in civil society. In particular he will address the integrated importance of museums, adchives and libraris for advacing the state of education at all levels including for countinuing adult education.

Speaker:

Jonathan Zilberg is a cultural anthropologist specializing in art and religion and in museum ethnography. He has been studying Indonesian museums for a decade and is particularly interested in museums as democracy machines and as post-colonial centers for advancing the ideology of pluralism in civil society. His immediate interests focus on Hindu-Buddhist heritage including the function of archaeological sites as open air museums as well as of museum collections and government depositories in terms of being under-utilized academic resources. For comparative purposes, he has studied museums in Aceh, Jambi, Jakarta and to a lesser extent observed select museums elsewhere in Indonesia. Currently he is CRCS UGM Visiting Scholar.

Secara historis dan genealogis, Yahudi, Kristen, dan Islam mengklaim memiliki hulu yang sama, yakni dari Ibrahim atau Abraham. Ketiga agama ini kerap mendaku dirinya masing-masing sebagai agama penerus dari tradisi Ibrahimiah, Abrahamic religion, atau millah Ibrahim. Karenanya, tak heran jika sampai saat ini, ketiga agama ini kerap bersaing dalam klaim kebenaran sebagai yang paling Abrahamic, atau sebagai pewaris paling sah atas millah Ibrahim yang mendakwahkan monoteisme sebagai inti ajarannya.

Abstract:

The Green Santri Network aims to be a socio-ecological movement by Indonesian Muslim groups, using Muslims’ own sensibility and ‘thought language’ to effectively disseminate messages about Islamic ecological values for survival and sustainability and to advance the idea of relocalization, or returning to a smaller scale, as self-reliant communities with simpler ways of living and with self-local governance. It comes out of my research into how Indonesian Muslim groups, including both the large-scale Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama and two examples of green intentional communities, Hidayatullah and An-Nadzir, can contribute toliving knowledge transmission or murabbias a way to make sustainability education relevant in the Islamic symbolic universe in the Indonesian context,based on the understanding that more than intellectual ability is needed to comprehend this knowledge; it must be made personal by living it.

Speaker:

Wardah Alkitiri earned her Ph.D. in Sociology at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, in 2016. Her dissertation was entitled “Muhammad’s Nation is called “The Potential for Endogenous Relocalisation in Muslim Communities in Indonesia”. She is founder of AMANI, a not-for-profit organization that aims to promote ecological sustainability through entrepreneurial creativity in Jabodetabek and Central Java.