Masihkah Islam dan demokrasi kompatibel di Indonesia ketika ormas muslim justru melemah di hadapan pemerintah?

Wednesday Forum Report

Ekspresi identitas Katolik Tionghoa di Muntilan merupakan bagian integral dari keberagaman pengalaman beragama dan telah melampaui doktrin kaku gereja.

Hafalan Shalat Delisa menghadirkan persoalan agama dan disabilitas di ruang publik, tetapi masih mengabaikan tantangan realitas penyandang disabilitas.

Sebuah diksi bukan hanya menjadi cerminan identitas pribadi maupun kelompok, melainkan juga menggemakan sikap eksklusivitas atau inklusivitas. Ketika digunakan dalam arena kontestasi politik, sosial maupun agama, bahasa dapat menjelma menjadi alat untuk menyatakan sekaligus menyingkirkan identitas tertentu.

Transformasi Modernitas yang Berlantas di Kanekes

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 15 Oktober 2024

Modernitas membawa tantangan bagi masyarakat Urang Kanekes. Namun, mereka punya cara tersendiri dalam menghadapinya.

Masyarakat adat Urang Kanekes—atau yang lebih populer dengan nama Baduy—di Banten selalu menarik perhatian para peneliti. Setidaknya ada 95 dokumen karya ilmiah yang memuat kata kunci “Baduy” dan 23 dokumen karya ilmiah dengan kata kunci “Kanekes” di situs Scopus. Ketertarikan ini muncul, di antaranya, karena masyarakat adat Kanekes sangat melestarikan ajaran tradisi leluhur sampai hari ini kendati wilayah adat mereka tidak jauh dari Jakarta, kota metropolitan serba modern.

Kedai kopi yang dianggap sekadar tempat transaksi ekonomi, ternyata menjadi ruang penting terciptanya sebuah dinamika relasi lintas etnis dan agama yang sarat akan luka masa lalu.

Keberagaman di Tengah Keberagamaan

Yohanes Leonardus Krismawan Anugrah Putra – 30 September 2024

“…because we believe the Indonesian voices need to be projected and amplified not just in Indonesia, but beyond as well”

Demikian sepenggal sambutan Brett G. Scharfis, Direktur International Center for Law and Religion Studies (ICRLS) dari Univeritas Brigham Young, dalam study visit bertajuk “Promoting Freedom of Religion or Belief in Indonesia: Challenges and Opportunities” di auditorium Pascasarjana UGM. Kunjungan belajar ini bukan sekadar visitasi institusional, melainkan juga ruang untuk membicarakan berbagai peluang maupun tantangan dalam membangun kebebasan beragama atau berkeyakinan (KBB) di Indonesia.

Dari Nurani Jadi Aksi

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 15 September 2024

Sebagian umat beragama menyadari gejala alam yang tidak menentu sebagai fenomena perubahan iklim. Lantas, sejauh mana pengetahuan agama mendorong umatnya melakukan kegiatan yang mendukung lingkungan?

“Agama memiliki efek ganda dalam membentuk perilaku ramah lingkungan,” jelas Iin Halimatusa’diyah, Direktur Riset Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat (PPIM) UIN Jakarta, lewat presentasinya bertajuk “From Belief to Action: Religious Values and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Indonesia” dalam Wednesday Forum (4/9).

Tanda-tanda kerusakan lingkungan ini sudah mulai terlihat. Erosi semakin sering terjadi, hasil panen menurun, dan banyak petani mulai bangkrut. Dalam situasi genting ini, alih-alih mengambil langkah konservasi lahan pertanian, para petani kentang terus memacu produksi kentang seolah tidak terjadi apa-apa. Masjid-masjid besar yang menjadi simbol kesejahteraan terus bermunculan, aktivitas keagamaan pun kian inten

berdasarkan data dari Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC), Bima merupakan daerah dengan rekam jejak aktivitas terorisme yang tinggi. Lantas, karakteristik keagamaan seperti apa yang tengah berkembang di antara masyarakat Bima? Sejauh mana karakteristik keagamaan itu mempengaruhi perkembangan terorisme di Bima?

Hijrah Minim Sampah:

Sebuah Ekolinguistik Islam ala Ibu Rumah Tangga

Nanda Tsani – 29 Juli 2024

Isu lingkungan tidak melulu berkutat pada hal-hal gigantis seperti krisis iklim, efek rumah kaca, kenaikan suhu bumi, mencairnya es Antartika, atau kepunahan massal. Bagi June Cahyaningtyas, isu lingkungan ialah juga tentang hal-hal keseharian yang tampak di pelupuk mata dan jangkauan tangan: wastafel mengilap yang kembali dipenuhi piring kotor, ember kosong yang penuh pakaian apek, hingga timbunan sisa makanan di tempat sampah dapur. Berangkat dari minat keamanan nontradisional dalam kajian Hubungan Internasional (HI), dosen HI Universitas Pembangunan Nasional “Veteran” ini meneroka dimensi keagamaan dalam praktik lingkungan berkelanjutan melalui pengalaman perempuan urban di Jawa. Hasil kajiannya itu ia presentasikan dalam Wednesday Forum, 15 Mei 2024, bertajuk “Sustainable Living Practice Among Urban Women in Java”.

Beradaptasi lewat Agama di Tengah Abrasi Pantai Utara Jawa

Rezza Prasetyo Setiawan – 20 Juli 2024

Salah satu dampak nyata krisis iklim ialah kenaikan air laut dan abrasi yang menenggelamkan daerah-daerah di kawasan garis pantai. Sebagai negara dengan garis pantai terpanjang di dunia, Indonesia menjadi salah satu wilayah yang paling terdampak. Lantas, bagaimana masyarakat Indonesia yang tinggal di kawasan terdampak beradaptasi dengan hal ini? Sejauh mana pemahaman dan praktik keagamaan mereka berperan dalam proses adaptasi tersebut?

Pertanyaan itu menjadi salah satu titik tolak disertasi Aliyuna Prastiti yang ia presentasikan dalam Wednesday Forum bertajuk “Making Sense of Religion in Adaptation Processes”, 8 Mei 2024. Dosen program studi Hubungan Internasional, Universitas Padjadjaran, ini meneliti dua komunitas masyarakat yang tinggal pesisir utara Pulau Jawa, yaitu Bedono, Kabupaten Demak, Jawa Tengah dan Pantai Bahagia, Bekasi, Jawa Barat.

Mempertahankan Agama Seadanya–Sebisanya di Negara Transit

Nanda Tsani – 16 Mei 2024

Pernahkah Anda transit di suatu bandara luar negeri? Transit selama 2 atau 3 jam mungkin tidak begitu terasa sembari menikmati fasilitas yang ada, tetapi bagaimana jika harus transit hingga puluhan jam? Betapapun berbagai aktivitas membunuh waktu dilakukan, tetap saja jemu itu datang, bukan? Sementara, para pengungsi dan pencari suaka di Indonesia rerata menjalani waktu transit antara 5 sampai 10 tahun penuh kegetiran.

Berangkat dari situasi yang dialami para pencari suaka ini, Realisa D. Massardi, Dosen Antropologi UGM, melakukan penelitian etnografi guna memahami manuver dan dinamika para remaja pengungsi dan pencari suaka dalam menavigasikan identitas keagamaan mereka di tanah transit. Selama kurang lebih 14 bulan dalam kurun 2016–2017, Dosen Antropologi UGM ini melakukan penelitian di empat lokasi pengungsian. Realisa memaparkan hasil penelitiannya dalam Wednesday Forum edisi 24 April 2024 bertajuk “Religion in Transit: Young Refugees Navigating Religious Sphere in Indonesia”.

Kendati lebih dari 90% responden di Indonesia mengatakan bahwa agama merupakan faktor penting bagi kebahagiaan mereka, agama bukanlah jawaban utama ketika mereka mengalami gangguan kesehatan mental.

Ketika terdesak oleh bencana yang sudah lugas di depan mata, masihkah faktor identitas sosial, politik, dan keagamaan menjadi penting? Apakah pertanyaan itu tidak lagi penting karena perbedaan sudah dilebur demi alasan kemanusiaan dan penderitaan bersama? Jangan-jangan, hilangnya pertanyaan itu justru adalah tanda marginalisasi terselubung yang justru makin tajam karena desakan keterbatasan sumber daya?

Agama dan spiritualitas seolah menjadi dua entitas yang berbeda. Di tengah zaman yang kian berpacu dan berkelindan, dinamika interaksi keduanya menjadi kunci untuk memahami hubungan antaragama di masa depan.

Pengalaman transendental nun di atas langit seringkali tidak bisa kita gapai dengan intelektual. Di sinilah humor bekerja. Dengan humor, agama yang adiluhung nan surgawi bisa menjadi sangat manusiawi dan membumi.

Membingkai Peristiwa, Menggali Imaji

Hanny Nadhirah – 17 November 2023

Bagaimana sebuah foto dapat memiliki pengaruh besar dalam membentuk pemahaman kita tentang suatu peristiwa?

Foto atau gambar yang sering kita lihat rupanya bukanlah sesuatu yang netral. Di dalamnya mengandung konstruksi makna dan kepentingan tersembunyi. Sebagai sebuah visualisasi atas peristiwa, foto berpengaruh besar pada cara kita memahami, merasakan, dan mengambil tindakan terkait peristiwa tersebut. Fenomena inilah yang Elis Zulianti Anis, dosen Universitas Ahmad Dahlan Yogyakarta, diskusikan pada Wednesday Forum (27/09) “Picturing Power: State Media, and Religious Representation in the 2015 Sumatra Forest Fires.” Elis memaparkan temuan penelitiannya terkait publikasi foto-foto media lokal saat kebakaran hutan dan lahan (karhutla) Sumatra tahun 2015.

Berebut Wacana Otoritas atas Tubuh Perempuan

Nanda Tsani – 17 November 2023

Bagaimana jika kelompok perempuan yang menyuarakan hak “tubuhku otoritasku” dibalas dengan “tubuhku otoritas tuhanku” oleh kelompok perempuan yang lain?

“The personal is political”. Slogan politis yang mencuat pada gerakan feminisme pada tahun 1960-an di Amerika Serikat ini sangat pas untuk menggambarkan dinamika pertarungan wacana atas tubuh dan otoritas perempuan. Pandangan perempuan mengenai otoritas tubuhnya tidak semata hal personal tetapi juga bagian dari gerakan politik yang terus dimobilisasi. Salah satu bentuknya ialah desakan kepada pemerintah untuk mengeluarkan kebijakan preventif maupun kuratif terkait kekerasan seksual yang banyak dialami oleh kaum perempuan.

Menggali Gaia

Hanny Nadhirah – 30 Oktober 2023

Bagaimana jika bumi yang kita sebut sebagai rumah, pada kenyataannya, adalah entitas hidup?

Pertanyaan di atas menjadi titik perbincangan pada peluncuran buku God and Gaia: Science, Religion, and Ethics on a Living Planet pada Wednesday Forum edisi spesial yang berlangsung di auditorium Sekolah Pascasarjana UGM (11/10). Peluncuran buku tersebut dihadiri oleh sang penulis, Michael S. Northcott yang kini menjadi adjunct professor di Universitas Gadjah Mada. Ia berbagi temuannya dalam mengonfigurasi ulang hubungan antara sains, agama, dan etika pada kehidupan di bumi ini.

Mewujudkan Hak Pendidikan Agama untuk Semua Siswa

Hanny Nadhirah – 24 Oktober 2023

“Setiap peserta didik pada sekolah berhak memperoleh pendidikan agama sesuai dengan agama yang dianutnya dan diajarkan oleh pendidik yang seagama.”

Amanat ini tercantum dalam Peraturan Menteri Agama Republik Indonesia No. 16 Tahun 2010 mengenai pengelolaan pendidikan agama di sekolah. Namun, dalam kenyataannya, apakah pendidikan agama telah diberikan kepada semua siswa dengan setara tanpa memandang latar belakang identitas mereka?

Pertanyaan ini menjadi pemantik diskusi Wednesday Forum (20/9) bertajuk “Fulfillment of Religious Education Rights for Minority Students” dengan narasumber Dody Wibowo dari Magister Perdamaian dan Resolusi Konflik UGM. Melalui studi kasus empat cabang Sekolah Sukma Bangsa, dosen yang akrab dipanggil Dody ini mengangkat dinamika implementasi pendidikan agama pada siswa nonmuslim di Provinsi Nangroe Aceh Darussalam dan Sulawesi Tengah.

Yang Terpenting Apa yang Ada di dalam Jiwaku:

Waria dalam Himpitan Normativitas Agama

Nanda Tsani – 04 Oktober 2023

Mungkin kita cukup familiar dengan dokumentasi keseharian religiusitas waria di Pulau Jawa, misal dari buku-buku Masthuriyah Sa’dan dan liputan dokumenter beberapa media yang berlatar Pesantren Alfatah Yogyakarta. Namun, tidak banyak yang mengulas dinamika pengalaman keagamaan waria di luar Jawa, utamanya di Indonesia bagian timur. Khanis Suvianita, alumnus program doktoral Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS) UGM, meneliti pengalaman keagamaan dari 57 waria di Gorontalo dan Maumere. Temuan tersebut ia diskusikan dalam Wednesday Forum, 13 September 2023, bertajuk “Lived Religion and Waria Religious Experiences in Eastern Indonesia”.

Apa yang terjadi jika tubuh manusia “dibebaskan” untuk bergerak?

Performa dan Polemik Kelompok Minoritas Agama di Ruang Digital

Maryolanda Zaini – 4 April 2023

Ucapan perayaan Hari Raya Nawruz dari Menteri Agama Yaqut Cholil Qoumas untuk pemeluk agama Baha’i beberapa tahun silam sempat menjadi polemik. Beberapa kelompok masyarakat menganggap Baha’i sebagai sebuah aliran sesat ketimbang sebuah agama. Polemik itu menunjukkan bahwa rekognisi terhadap kelompok minoritas agama masih menjadi persoalan serius di negeri ini. Tak dinyana, pandemi Covid-19 membuka peluang bagi kelompok minoritas agama untuk mengekspresikan keyakinannya, salah satunya melalui platform digital. Ruang di dunia maya ini menjadi ruang potensial bagi titik temu kebebasan beragama atau berkeyakinan di Indonesia. Namun, ekspektasi itu rupanya tidak selalu berbanding lurus dengan realita. Ujaran kebencian dan perlakuan diskriminatif rupanya masih juga ditemui dalam platform digital tersebut.

Rumah Sakit sebagai Ruang Perjumpaan Antaragama

Vikry Reinaldo Paais – 18 April 2023

Sakit adalah kerapuhan manusia yang tidak terhindarkan. Setiap orang apa pun agama, etnis, ras, dan status sosial, bahkan dokter sekalipun, tidak bebas dari sakit. Karenanya, kebutuhan akan kesehatan menjadi urgen dan harus segera dipenuhi. Fenomena inilah yang mendesak sebagian besar organisasi sosial nonpemerintah ikut serta dalam penyediaan layanan kesehatan, termasuk lembaga keagamaan. Banyak lembaga agama yang memprakarsai pendirian rumah sakit. Meski berbeda keyakinan, tujuan mereka sama: menyelamatkan nyawa manusia.

Menafsir Queer, Membuka Dialog Antaragama

Bibi Suprianto – 12 April 2023

Identitas queer di masyarakat terus mengalami dinamika sosial. Sebagian besar masyarakat masih menstigma identitas queer sebagai aneh dan tidak normal. Di saat yang sama, kelompok yang mengaku sebagai queer terus mengalami diskriminasi moral, sosial, maupun aktivitas keagamaan. Dinamika sosial ini telah terjadi di berbagai belahan dunia, tak terkecuali Indonesia. Di Aceh, Indonesia, misalnya. Pada 2017, pasangan queer di Kota Banda Aceh menjalani eksekusi berupa hukuman cambuk karena dianggap tidak bermoral dan hina. Kejadian ini membuat saya bertanya, apakah identitas queer tidak memiliki kebebasan dalam hak kehidupan sosial dan agama?

Melintasi Sarang Naga di Bawah Angin:

Ragam Pecinan di Nusantara

Refan Aditya – 20 Maret 2023

Memori nasional tentang masyarakat keturunan Tionghoa di Indonesia sering kali dibayangi oleh pengalaman pahit yang mereka alami. Yang paling kentara ialah pelarangan perayaan adat Tionghoa di ruang publik dan pelucutan identitas ketionghoaan melalui kebijakan asimilasi paksa di era Orde Baru. Sentimen antikomunis serta kecemburuan sosial terhadap masyarakat keturunan Tionghoa juga menjadi bahan bakar stigma yang getarnya masih terasa sampai hari ini. Klimaksnya, di titik akhir kekuasaan Soeharto, masyarakat keturunan Tionghoa di berbagai kota menjadi korban anarkisme massa yang tak terperi. Namun, sejarah membuktikan, betapapun dalam luka itu, selalu ada rumah tempat trauma kolektif tersebut disulih menjadi daya; tempat harapan masih bisa dianggit bersama: pecinan.

Menimbang Keberagaman di Bawah Raja Anglikan

m rizal abdi – 1 Maret 2023

Wafatnya Ratu Elizabeth II beberapa waktu silam tidak hanya menyisakan duka bagi warga Inggris dan keluarga kerajaan, tetapi juga menggurat pertanyaan besar: Apa yang akan terjadi dengan masa depan Kerajaan Inggris, pusat dunia bagi Gereja Anglikan?

Jemaat Gereja Anglikan patut berdebar soal ini. Mei 2023 nanti, Uskup Agung Canterbury akan mengurapi sang calon raja dengan minyak suci, memberkati, dan menahbiskannya sebagai raja baru Inggris. Saat itu, Raja Charles III bukan hanya menjadi pemimpin bagi Britania Raya, melainkan juga Gubernur Tertinggi bagi gereja induk Anglikan sedunia yang juga bergelar Fidei Defensor, ‘sang pembela agama’. Menariknya, jauh sebelum naik tahta, Charles III sudah menyatakan bahwa dirinya ingin dikenal sebagai “Defender of Faith” atau ‘pelindung agama’ alih-alih sebagai pembela agama tertentu (Defender of the Faith). Pernyataan Charles pada wawancara tahun 1994 tersebut tentu saja memancing kontroversi dan kegelisahan saat itu. Bahkan, muncul usulan penangguhan atas penobatannya jika suatu hari ia mewarisi tahta Inggris.

Menemukan Allah: Tantangan Menjadi Saint Queer di Tengah Arus Konservatisme Agama

Refan Aditya – 22 November 2022

Mengerasnya konservatisme agama di Sulawesi Selatan menjadi ancaman bagi komunitas Bissu sebagai pelestari dan pemimpin agama leluhur Bugis. Yang paling kentara adalah upaya untuk melucuti status gender nonbiner para Bissu. Namun, di tengah masifnya konservatisme tersebut, para Bissu tak berhenti mencari dan menggali ruang-ruang spiritualitas dalam dirinya dan tempatnya di masyarakat Bugis saat ini. Dinamika itu menjadi bahasan Wednesday Forum, 12 Oktober 2022 bertajuk “Queer Spiritual Space in Bissu Community South Sulawesi: In Search of Allah”. Diskusi ini disajikan oleh Petsy Jessy Ismoyo yang merupakan mahasiswa ICRS dan pengampu program studi Hubungan Internasional di Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana.

Otoritas Agama, Pengalaman Keseharian, dan Peran Ulama Perempuan

Andi Alfian – 20 Oktober 2022

Sebagai salah satu pemegang otoritas keagamaan, ulama tidak hanya bertugas membimbing, tetapi juga mengeluarkan pendapat berdasarkan prinsip-prinsip hukum Islam terkait persoalan yang dihadapi oleh umat, baik ritual keagamaan maupun aktivitas sosial kemasyarakatan. Pendapat-pendapat mereka inilah yang kemudian disebut sebagai fatwa.

Di Indonesia, dan banyak negara mayoritas muslim lain, perumusan fatwa nyaris semuanya dilakukan oleh ulama laki-laki. Padahal, sejumlah persoalan yang mereka diskusikan adalah hal-hal yang sangat dekat dan berimbas langsung dengan kehidupan dan pengalaman para perempuan muslim. Menanggapi situasi ini, gerakan kaderisasi ulama perempuan di Indonesia mulai tumbuh dan merebak dalam dekade terakhir. Salah satu tonggak pentingnya adalah Kongres Ulama Perempuan Indonesia (KUPI). Kongres yang diadakan di Pondok Pesantren Kebon Jambu, Cirebon, Jawa Barat, pada 2017 ini berupaya menggerakkan dan menguatkan kelompok ulama perempuan agar terlibat aktif dalam penyelesaian persoalan umat muslim di Indonesia. Kongres tersebut menginspirasi Nor Ismah, Kepala LPPM Universitas Nahdlatul Ulama Yogyakarta, untuk meneliti dan mengkaji persoalan ini lebih lanjut.

Sejauh mana keberadaan kecerdasan buatan mampu membantu agama menjawab tantangan zaman? Ataukah keberadaaanya justru membuat agama semakin tidak relevan dan menggantikannya?

Di kala kita sedang berdiskusi saat ini, atau membaca tulisan ini, ribuan bayi mati setiap hari dan puluhan ribu lainnya kekurangan air bersih. Lantas, apa yang bisa kita lakukan sebagai akademisi?

Pendekatan etika keagamaan adalah ruh yang menjiwai program revitalisasi gambut dan mangrove sekaligus memastikan keberlanjutan upaya pelestarian ini. Utamanya, ketika program ini usai.

Dua kelompok perempuan dari dua desa dan dua agama berbeda berkumpul untuk saling membacakan kitab suci lalu berbagi refleksi. Merekalah para perempuan pelintas batas yang membuka sekat-sekat dialog lintas agama.

Ruang ICU Covid-19 yang mulanya sebatas ruang perawatan kini bertransformasi menjadi ruang suci tempat dialog antaragama terjadi. Paramedis di sana merupakan agen yang mentransformasi ruang tersebut atas dorongan solidaritas dan empati.

Bicara masturbasi bukan hanya bicara tentang “diperbolehkan” atau “dilarang”, melainkan juga mengenai hierarki institusi bernama agama.

Meski sudah ratusan tahun hidup bersama, Tionghoa Kristen merupakan salah satu identitas masyarakat yang paling sering disalahpahami di Indonesia. Stereotip yang paling melekat—bahkan hingga hari ini—di antaranya eksklusif, punya hak istimewa dalam perekonomian, agen kristenisasi, bahkan diragukan nasionalismenya.

Madura merupakan mikrokosmos bagaimana Islam dan politik berbaur, berbentur, sekaligus berusaha membentuk hubungan yang saling menguntungkan.

Tidak mudah menjadi individu tak beragama di negara yang menjunjung ketuhanan sebagai salah satu dasarnya. Stigmatisasi dan diskriminasi terus membayangi. Lalu, bagaimana umat tak beragama di Indonesia menegosiasikan identitas tersebut?

Pasca-Reformasi, semangat generasi muda di berbagai daerah untuk menggali kebudayaan lokal mereka kembali muncul. Akan tetapi, jurang antargenerasi telah terjadi. Bertolak dari keresahan tersebut, Lakoat.Kujawas berusaha menjembatani keberadaan adat, modernitas, dan gereja di Mollo, Timor Tengah Selatan (TTS). Salah satunya melalui sastra lokal.

Rimpu telah menjadi simbol identitas dan keseharian masyarakat muslim Bima semenjak abad ke-17. Akan tetapi, pemaknaaan dan penggunaannya berkembang seiring dinamika masyarakat.

Religious Studies often gives much emphasis on written sources while neglecting the significance of sound in the identity formation of certain religious communities. The case of the Matua community, discussed in one of this month's Wednesday Forums, challenges that tendency.

In the Anthropocene, humans are the most complicit in rapid environmental degradation. What can religious traditions offer to resolve this problem? Michael Northcott discussed this issue at the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum.

A report on the Wednesday Forum lecture with Dr Zainal Abidin Bagir.

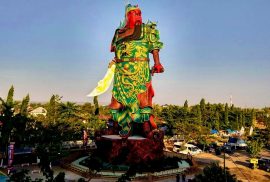

Liputan Wednesday Forum 20 Feb 2019 tentang kasus Patung Dewa Kwan Kong di Kelenteng Kwan Sing Bio, Tuban.

Komunitas berisi para pemuda Timor memberdayakan masyarakat lokal di sekitar Mollo, Timor Tengah Selatan, NTT, dengan mengembangkan literasi dan wirausaha sosial berbasis adat.

A report from the Wednesday Forum presentation by Elizabeth Inandiak.

A report of the Wednesday Forum talk by Dr Abd Gaffar Karim from FISIPOL UGM.

A report from the Wednesday Forum talk by Dr Achmad Munjid.

A report of the Wednesday Forum presentation by Barbara Andaya, professor of Asian Studies at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa.

A report from the Wednesday Forum presentation by Dr Magdy Behman on April 18, 2018.

A report from the Wednesday Forum presentation by Frans Wijsen on March 28, 2018.

A report on the Wednesday Forum presentation by Ihsan Ali-Fauzi, the director of PUSAD Paramadina.

A report from the Wednesday Forum presentation by Dr Wening Udasmoro.

A coverage of Mark Woodward's presentation at CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on the Muhammadiyah Association of Singapore.

Eight points of the Protestant Reformation's legacies to the modern world, as explained by Prof. Hans-Peter Grosshans at CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum.

A report on the presentation by Evi Sutrisno on Indonesian Confucianism at the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum.

A report of the Wednesday Forum presentation by Linda Yanti Sulistiawati, lecturer at the Faculty of Law, UGM.

A report of the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum presentation by Dr Haidar Bagir on the need for a paradigm shift in understanding Islam.

Wednesday Forum report of the presentation by Maria "Deng" Giguiento, a peacebuilding activist and trainer at Mindanao Peacebuilding Institute.

A report of Mun'im Sirry's presentation on Islamic christology at the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on September 27, 2017.

A report on Dr Hew Wai Weng's presentation at the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum, August 30, on the dakwah style of Chinese-Indonesia Felix Siauw.

Sharing her experience as a German woman converting to Islam, Dr Katrin Bandel gave a presentation at the Wednesday Forum.

Anna M. Maćkowiak, a doctoral student from Jagiellonian University presented her research in Wednesday Forum about how Islam has been perceived in her home country, Poland.

Anang G Alfian | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

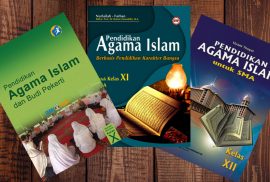

At the CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on April 12th, 2107, Sawyer Martin French, a research fellow at the Institute for International Studies at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Universitas Gadjah Mada, gave presentation on the government-mandated curricula of Islamic education in public high schools. He took several public high schools (Sekolah Menengah Atas, SMA) in the province of Yogyakarta, with the method of classroom observation, interviews with teachers, and student focus group discussions in a few schools. More importantly, he also presented his research on Islamic textbooks used in those high schools which he observed have undergone content changes.

In his presentation, French showed that each political period has a difference in the emphasis of the contents of the Islamic textbooks used in SMA. There are three political periods where curricula for Islamic education in SMA have evolved, from the 1994 curriculum, which was formed under the Suharto New Order’s regime; then replaced by the 2006 curriculum under the post-reformation period; and the latest, 2013 curriculum. French shows the content of the Islamic curricula has undergone several changes, three main of which are that related to tolerance, democracy and gender issues.

Regarding democracy, French mentioned an example of 1994 Islamic textbook mentioning the importance of “mushawarah” (lit. consultation to each other) as an Islamic teaching in managing Indonesian politics and governmental administrations. The 2003 textbook mentioned the importance of being a good citizen, meaning a democratic citizen, by further interpreting the meaning of mushawarah. This shows the change due to discourse on democracy generated by reformation. In the 2013 textbook, there is a reference to put more details of how Indonesia democracy should take the ideal shape, and that is to take the example set by the Medinan charter during the time of the Prophet.

Relating to tolerance, the textbooks show changes in the way Muslim should deal with other religions or Islamic sects. In the 1994 textbook, Pancasila was referred to as be the basis of harmony among religious communities while in the 2006 textbook, tolerance can be built along social matters but not along religious lines. The 2013 textbook mentioned that tolerance is a tool to unite the nation, but there are a few sentences which suggest intolerance against some Islamic sects, such as that some Sufi orders practice bid’ah or heretical rituals and that Shiites and Ahmadis are deviant and beyond the limit of tolerance.

As on gender issues, the dominant content of the 1994 textbook upholds the obligation of men as the leader of the family and women as the one who must be obedient to her husband. This was set as an example of a good family. In the 2013 textbook, the focus was more to a companionate marriage and mutual relationship. The notions of housewife and superiority of men which were mentioned in the previous textbooks are now gone and replaced by sentences suggesting a more equal relationship between the husband and the wife, though there is still an emphasis that, despite the same level, “their roles are different.”

*Anang G Alfian is CRCS student of the 2016 batch

Anthon Jason | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

In Indonesia, people can be called by their homeland’s name, such as orang Batak, orang Sunda, orang Manado and so on. The Indonesian concepts that are tied tightly to ideas of land, community, and cosmology referred to as adat have a dynamic and complex relationship to people’s religious identification and how they understand their identities. People can be emplaced or displaced in regard to how their religious identity relates to their cultural identification with particular places. While emplacement is the process by which people identify themselves with a place, displacement is a dislocation, removal, expropriation, takeover, or ideological process to refute claims of rights over land, the use of cultural symbols, or the ability of people and groups to self-identify.

Anang G Alfian | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

As a product of the globalized world, social media have created a virtual space of communication and interaction. Many people use it with enthusiasm as it helps humans build communication and connectivity much faster than ever before. On the other hand, many consider this phenomenon a challenge for living ethically and productively.

Dealing with this topic, Wednesday Forum on February 9th 2017 held a discussion on “wefies” (group self-portraits posted on social media) in relation to the Islamic concept of riya’ (showing off piety). The two speakers, Fatimah Husein, currently teaching at CRCS/ICRS as well as UIN Sunan Kalijaga, and Martin Slama of the Institute for Social Anthropology at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, presented the emerging phenomenon of online piety in Indonesia, especially on how Muslims rethink riya’ in today’s popular “wefie” culture. The presentation was based on Husein’s article titled “The Revival of Riya’: Displaying Muslim Piety Online in Indonesia” which has been submitted for a virtual issue of American Ethnologist and Slama’s research project on “Islamic (Inter)Faces of the Internet: Emerging Socialities and Forms of Piety in Indonesia” funded by the Austrian Science Fund.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | WedForum Report

Going to the cinema is a new social practice in modern society. To some extent it can also be perceived as a spiritual practice. Dr Nacim Pak-Shiraz, the Head of Persian Studies and a Senior Lecturer in Persian and Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh and guest speaker at the Wednesday Forum on February 9th, studies this paradox in the dynamics of Iranian cinema. She began by noting that there has been only a little academic attention to the movies based on Quranic epics, in contrast to what has happened with Biblical epics from Hollywood.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | WedForum Report

Jonathan Zilberg, a cultural anthropologist whose research and advocacy focuses on museum ethnography, argued that Indonesian museums face such problems as performance, transparency and accountability, but they have the potential power to promote pluralism to the public. In his February 1st Wednesday forum presentation, he raised questions as to how Indonesian museums can be a strong bond to serve Indonesia’s diversity.

Based on his research in National Museum of Indonesia in Central Jakarta, Zilberg argued that museums are an extension of culture and identity. He conducted his research by closely examining the activities of visitors of National Museum. He took photos from different angles and then reflected on how visitors interact with the objects on display. He stressed that a museum that functions well should be a place to learn and display democracy. Different people come to the museum with various interests. These differences can lead them to learn about pluralism in comfortable ways.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Al Makin, a lecturer from ICRS and Ushuluddin Faculty in UIN Sunan Kalijaga, gave a fascinating presentation about his newest book Challenging Islamic Orthodoxy (Springer, 2016). He began his presentation by commenting that his research on prophethood in Indonesia may not be very new to the ICRS and CRCS community, but discussion of the polemics of prophethood is interesting as Indonesia is home for both the largest Muslim population of any country in the world and to many movements led by self-proclaimed prophets after the Prophet Muhammad. In Al Makin’s perspective, we should see this phenomenon from a different perspective, as part of the creativity of Indonesian Muslim society.

In 1993, the Ministry of Religious Affairs issued a selection of characters of what constitutes religion, include the definition of the prophet, a requirement of recognized religions. According to the Ministry of Religious Affair, prophets are those who receive revelation from God and are acknowledged by the scripture. However, following Islamic teaching, Muhamad is the seal. God no longer directly communicates with humankind. In Al Makin’s definition, prophets are those who, first, have received God’s voice and, second, establish a community and attract followers. He also reported that the Indonesian government has listed 600 banned prophets that fit these criteria. Interestingly, Indonesian prophets tend to come from “modernist” backgrounds connected to Muhammadiyah, which rejects other kinds of traditional and prophetic religious leadership, like wali and kyai.

After two years of trying, Al Makin gained complete trust from one well-known prophet in Jakarta, Lia Eden, and her community of followers. The wife of a university professor, Lia Eden was famous as a flower arranger and close to members of President Suharto’s circle. She quit her career when she was visited by bright light she later identified as Habibul Huda, the archangel Gibril. After that, she became prolific in her prophecies. She found many skills that she had not had before, like healing therapy. Her circle become a movement called Salamullah, meaning “peace from God” but also referring to salam or bay leaves, used in her healing treatment.

In orthodox Islam, there are no women prophets and no prophets after the Prophet himself. The ulama declared her and her followers heretics. Lia Eden returned the criticism, accusing the ulama of being conservative and criticizing Islam as an institution, especially how the ulama council uses its political power and authority.

Al Makin closed his presentation by showing the way public has responded to Lia Eden. This movement can be considered a New Religious Movement sparks controversy because of how they attract followers. In Indonesia it is more about theology than political or economic interest like it is elsewhere. Ultimately, Al Makin argues that Indonesia’s prophets should be recognized as unstoppable—they usually become more active when in prison—but should be seen as part of the wealth of Indonesia pluralism.

Al Makin responded to a question from Mark Woodward about why Lia Eden’s community with only 30 members would become such a big problem for the government by citing Arjun Appadurai, who has argued that a small number becomes a threat to the majority in terms of its purity. It is true that she has a very small number of followers but she is also very bold and outspoken in deliver her messages constantly sending letters to many political leaders, including the ambassadors from other countries and issuing very public condemnations. Greg, another lecturer from CRCS, also asked why she is called bunda and whether she is making a gender-based critique. Al Makin answered that there have been a few other women prophets besides Lia Eden in Indonesia and that Lia Eden’s closest associates are women.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Akhmad Akbar Susamto, active lecturer in in the Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) started his presentation in Wednesday Forum about Islamic and Western economics by explaining the background behind the academic discipline of Islamic economics. Islamic economics has been developed based on a belief that Islam’s worldview differs from that of Western capitalism. Islamic economics has its own perspectives and values related to how decisions are made. According to Susanto, the boundaries of Islamic economics as a social science or a discipline are closer to economics than to theology or to fiqh.

There is a strong impression telling that Islamic economics is in complete opposition with the Western conventional economics. Susanto argued that such an impression is wrong: although the Islamic worldview does differ from the worldview of Western capitalism, Islamic economics as an academic discipline was established to realize the Islamic worldview and can stand together with conventional economics established in the West. Each can benefit from the other.

Susanto introduced a new framework for Islamic economic analysis that lays a foundation for the complementarity between Islamic and conventional or Western economics. This new framework can resolve the dilemma faced by Muslim economists and help to establish Islamic academic disciplines alongside their Western peers.

This new framework introduced by UGM economists to define the scope and methodology of Islamic economics. It is called the Bulak Sumur framework. The name is taken from the name of the place where UGM is located. Based on the framework, an economy can be considered Islamic as long as it constitutes visions and methods which are consistent with Islamic worldview and it is able to help and guide societies to transform their economy towards the achievement of welfare as Islamic worldview dictates. To be Islamic requires not only separating the sacred and profane but being able to depict both the current state and the ideal state. Thus, the Bulaksumur Framework includes:

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

The aim of this research is to examine the background of the rumors spread in Sumba especially in relation to “foreign intruders”. For Kabova, Sumbanese rumors in general are an effort to define themselves in opposition to outside forces and also a tool for maintaining the norms within the society. Rumors according to Kabova are uncertain knowledge that spread rapidly. She added also that rumors are stories which are believed by the community and transmitted to them because they resonate with their life circumstances and address their social and/or moral concerns. Rumors also are not something that needs to be proved or disproved.

In Sumba, Kabova focused her research in Waikabubak the west part of Sumba island. In her previous research, Kabova tried to find some pattern and relation in the motivation and imagination of the incoming tourists. In this project, she did some structured interview with local people as well as participant observation. In her efforts to gather information, Kabova also tried to gather some informal narratives to her time spent with the local people of Sumba.

One of the myths perceived by the Sumbanese is the myth about sacrifices for bridge construction. Resurfacing from time to time, these rumors say that victims’ heads and other parts of the body are used to help the building construction. They use the terms penyamun and djawa toris to refer to anyone trying to kidnap local people, especially children, and take their body parts. One of the participants told her: “In the past we recognized djawa toris immediately, because a djawa, unlike us, would wear long trousers.” Djawa in the Lali dialect is anyone whose immediate ancestry is not from Sumba; djawa toris are those looking for body parts.

Following that, another idea about djawa toris or penyamun also talk about suspiciousness. “Maybe during the day he is good, but inside he is rotten. He is alone, he has a machete and in the night we will slit our children’s throat”. (Sumbanese woman talking about an Australian tourist). Due to this suspiciousness, tourists who do something outside the norm are considered djawa toris. Some places that tourist normally don’t go to will invite suspicion for the locals; tourists should stay in the cities and villages, should not go to the forest. If they go somewhere outside the norm, they should explain where they are going, what they are going to do, how long, and why.

Another aspect of the rumors is the prominence of electricity. Kabova told her stories about how the old people are usually afraid of the electricity because they think it consists of human fresh blood. Blood in Sumbanese narrative is a symbol of power. In the context of Sumba, blood has duality. The cold blood and the hot blood. Hot blood is the blood where people die in a harmful way, like in violence. This hot blood believed to has ability to speak. By her explanation, the roots of the rumors could be traced back to the era of slave trade past centuries ago. The cultural memories remain in people’s remembrance through the narratives that have been told times to times. For example, she quoted Needham (one of the researchers in Sumba): “When I lived in Kodi , in the mid-fifties, the appearance of a strange vessel out at sea, or just a rumor of one, would provoke all the signs of a general panic; men look fiercely serious, and screaming women dashed to pick up their children.”

The scenario of the rumors happened in this way. The victims are the Sumbanese, Lolinese, Kabihu members, uma members. The offenders are outsiders: missionaries, colonizers, Indonesian incomers, tourists, and state agents. Rumors can also be understood as a form of protest against the loss of political autonomy. The last point Kabova made about the circulation of the rumors as the mechanism of social control. It is a way of the local people to maintain norms. Deviation is punished by with accusations and then ostracism. For example, a man (former prisoner) accused of being a penyamun was completely ostracized by the community and those around. Mentally ill people are also often accused of being penyamun. The other way this rumors also have been used perpetually by the thieves who want to steal the animals in their neighborhood.

Some fascinating questions came up in the Q and A session. One of them is the role of religious leaders in the rumors spreading and why people still believe it up to now? Kabova told that the reactions toward the rumors are different between people in the village and in town. People keep using the story for some reason like to educate their children even though they do not believe in it. Also, the social gap between the old and younger generation shows different reaction. Subandri also came up with the story that almost in every place of Indonesia we can find narratives of head hunters. And children are always the target. Kabova thinks it is because the children are the weakest among the society because they need protection from others.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

“Like the study of feminism, masculinity can be an important approach in religious studies. The study of masculinity emphasizes how man superiority has been graded or perceived from time to time that in turn it becomes a norm for society.”

“Like the study of feminism, masculinity can be an important approach in religious studies. The study of masculinity emphasizes how man superiority has been graded or perceived from time to time that in turn it becomes a norm for society.”

Rachmat Hidayat, a Project Director in Kalijaga Institute for Justice, State Islamic University Sunan Kalijaga, who shared his research in the weekly CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum, September 14, 2016, is and experiences about Muslim men from three Southeast Asia countries—Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia—living for years in Australia. His research questions are grounded in the problem of masculinity in Islamic studies.

In Muslim majority society, the figure of man is portrayed as the “imam” or, in a very general sense, the leader of the family. In the Muslim based society, the doctrine that male is the leader is embodied in the daily practices. The role as man in Muslim families anchors their responsibility in leading the household but, in contrast to the men living the non-Muslim society, the meanings and understandings change.

Building a framework that can help masculinity to be accepted in Islamic studies, Hidayat argued that just like the study of feminism, masculinity can be an important approach in religious studies. In general, the study of masculinity emphasizes how man superiority has been graded or perceived from time to time that in turn it becomes a norm for society.

The problem of masculinity in Muslim men living in Australia is in the sense of manhood within the family structure. In such context, the challenges are coming from the liberal and secular societies. Before explaining more about that problem, Hidayat described masculinity and how it works in the society. Masculinity is taking man as a gendered subject and perceiving men’s identity as related to but different to women. Men’s identity was constructed within certain historical, cultural, and social process. But this construction and the identity itself changes from time to time.

Furthermore, Hidayat asserted that gender construction and the meaning of the self is something that people define and negotiate every day because the discourse of the self is related to other. There are valves imply in Men’s identity. The gender construction adding the values such as bravery, toughness, rationality, to men’s identity and make people unconsciously define men in those values. In doing so, in Muslim community, being a man means being religious and strong at the same time. The practices of being a man in Muslim based society are included the practice of competition, dominance, and fathering. It shows that performance as a man cannot be separated to the relation with woman and kids.

Masculinity only can be defined and identified in the relationship therefore to study about masculinity in Islamic Studies, the approach must be done by examining men also as religious gender actors. In the context of secular of Australian society, the Muslim men identify challenges by some unfamiliar condition. Muslim men need to negotiate their position under the relation that lies between the Muslim women-Muslim brotherhood-the divine and the society itself.

With their various background, the 25 Muslim men in Australia whom he interviewed compromise and negotiate their position as Imam in their daily basis which relates to the men’s role as bread-winner in family. Facing the adversity and limitation, the Muslim men build their survival mechanism. In that survival mechanism, men need to share the authority, responsibility, and power to their partner who have more opportunity to get the money. Hence, some Muslim women replace the role of Men as bread-winner.

Responding to those facts, Samsul Maarif from CRCS asked whether women might also have masculinity and thus the term masculinity is not exclusive for men. “Masculinity, like feminine, is construction and it shows particular quality rather than embedded on sex,” said Hidayat. Within this framework, Muslim Southeast Asian women in Australia who perform their role as bread-winner also have masculine quality. However, as Hidayat underlined, men’s role as Imam is a non-negotiable status for men. Thus, responding to the challenges in every day live in Australia, Muslim men adopt some norm and apply it to the family as an act of negotiation. For example, the practice of partnership and individual freedom equality. Even when the wife becomes the bread-winner, the husband still has authority to manage the family. Furthermore, by giving permission to the wife for working, a husband serves their role as humble and just Imam because he aware of its limitation and humbly accept it. Hence, now Muslim men understand the role of Imam differently: as an act to love, to sacrifice, to share, and not being selfish with their family member.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

In a world so full of complexity, how does intimacy work? To Dian Arymami, it is very significant and important to revisit the understanding of intimacy because she observes the transformation of intimacy is connected to the transformation of society. The practice, the understanding of intimacy have been reconstructed from time to time. Usually people would think about intimacy as an act of loving, but up to now there are many cases show that intimacy could be something out of love, outside of committed relationship and, to be more precise, outside of marriage. Moreover personal needs and desires are also part of our religiosity. Religiosity and intimacy are not totally opposed to each other.

Dian Arymami’s ongoing research on new kinds of intimacy in the phenomenon of extradyadic or non-monogamous relationships that have quickly become widespread in urban areas of Indonesia is not advocacy on behalf of a group of people but she insists that she is studying the voices of the voiceless. Their emergence can be seen on a practical level as a rebellion against the structure and social fabric of Indonesian society but at the same time as part of an ongoing shift of ideological values and norms. Those who practice extradyadic relationships are a voice that could not be heard by the society because people would always claim that the problem is in person not society. We must think about this kind of intimacy as a social phenomenon and not a personal disease or failing.

Therefore, Dian came up with the signs of embodied practice of intimacy in the schizophrenic society. It related to something that material not representation. It is social not familial and she continue by saying that it multiplicity not personal. Many things transform relationships. According to the cases that Dian come up with, the social media is one of the biggest influence in transforming relationship in society. The discourse about intimacy embodied in the way people perceive things like divorce, sexuality, dating style, poly-amor trend and many others to follow. To define schizophrenic society, she refers to the theory of Gilles Delueze and Felix Guattari about the process of schizophrenia. Unlike Freud’s understanding about paranoia, the schizophrenic term in Delueze shows a condition of an experienced of being isolated, disconnected which fail to link up with a coherent sequence. She than continues that no one is born schizophrenic. Instead, schizophrenia is a process of being. In the schizophrenic society, everyone experiences diverse meanings in relation to other objects, and, in the other times or places, no meaning at all. In other words, meanings are based on the schizophrenic’s object experiences, but it is society itself that must be understood as schizophrenic.

By highlighting her respondents’ experiences, Dian shows that there are many consequences of the practice of intimacy or intimate relationships in (as) the schizophrenic society including “value crash,” double life, “time and place crash” and many others. In extradyadic relationship people become a substitution for something that they cannot fill.

In the question and answer session, there were many fascinating questions about this topic. Zoyer, a researcher concerned with on-line dating in Yogyakarta, offered the idea that the complexity of intimate relationships in urban areas in Indonesia is affected by the cultural expectation that young people marry by certain ages. That is why people are trying to free themselves by “jumping into the extraordinary.” The other question brings us to a reflection about what are the practitioners of these extradyadic relationships are becoming in society. Dian answered by changing the question: instead of questioning a person’s behavior, we must question society. Dian closed her remarkable presentation by stating that the idea of love is not exclusive and absolute.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Elizabeth Inandiak began her presentation in Wednesday Forum with the familiar fairy tale opening “once upon a time.” A distinguished French writer who has lived in Yogyakarta since 1989, she herself is a story teller. In her newest book Babad Ngalor Ngidul (Gramedia, 2016), she tells how she came to write her children’s book The White Banyan published in 1998, just at the end of the New Order. She explained that the book grew out of the tale of the “elephant tree” tale that she created herself after she “bumped” into a banyan tree while she was wandering in her afternoon walk back in 1991. Her story became reality when shemet Mbah Maridjan, the Guardian of Mt. Merapi, and was shown a sacred site at Kaliadem on the slopes of Mt. Merapi, a white banyan tree. Her new book about the conversation between the North and South areas of Yogyakarta takes its name from Babad (usually a royal chronicle, but here of two villages) and the phrase Ngalor-Ngidul, which in common Javanese means to speak nonsense but for her is about the lost primal conversation between Mount Merapi as the North and the sea as the South.

Quoting the great French novelist Victor Hugo’s remark that “Life is a compilation of stories written by God” Inandiak highlighted how meaning is found in stories which come before larger systems like religion. In her book and her talk, she told stories from her experiences with the victims of natural disasters in two communities, one, Kinahrejo, in the North and one, Bebekan,in the South. Inandiak explained that the process of recovery after a natural disaster is a process with and within the nature. It is about the reconciliation between human communities and nature. In natural disasters people mostly lose their belongings such houses, money, clothes and domesticated animals, but, she said, the most important thing is not to lose their identity. Houses can be rebuilt, but once people lose identity they don’t know how to rebuild anything else. Inandiak spoke about the disaster as a conversation between the North and the South. This is also a kind of stories that helps people deal with their situation, by accepting that disaster are part of natural cycles.

Inandiak also spoke about rituals. First there were the rituals enacted by Mbah Maridjan and Ibu Pojo, the shamaness who was his unacknowledged partner, to connect human communities and nature. The offering ritual they made to Merapi included three important layers that describes their own identities: ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam especially Sufism. Despite all the issues that Mbah Marijan and Ibu Pojo faced before they died in the 2010 eruption, they insisted what they were doing is an act of communicating with the nature that was their home. Second, in order to overcome the difficulties after a disaster, stories and ritual mean a lot for reestablishing the victims’ identity. By doing rituals like dancing or singing, they connect to the wishes that become true. The wishes that they made bring such a different in their perspectives in continuing life. Through ritual people want to get connected with nature and Inandiak told how she helped these villages rebuild their identities.

In the question and answer session, we were moved by many fascinating question about the relation of nature and person. One of them is how the three layers in Javanese ritual—reverence for ancestors, Hinduism and Buddhism, and Islam, particularly Sufism—deal with the interference of world religion. Inandiak responded that there must be many changes brings by the world religion, especially in Kinahrejo, where Mbah Maridjan faced pressure from fundamentalists. The way villagers perceive myth changes from time to time. Their Muslim-Javanese identity is something they need to maintain in negotiation. In answering the issues about participants in the rituals wearing hijab, Inandiak argued that these layers should be clearer. They are not rooted in one story. But to maintain the customs is also important.

Inandiak closed her presentation with a remarkable message that disasters come from the interaction of people and nature but no one should feel guilty or think that any disaster is the result of sin or human mistakes. The most important things are not to give up and to work to rebuild identity.

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Corruption is one of many problems that Indonesia as a nation faces. It is not only a law-related problem but also a cultural problem. As such, culture and the values it promotes could also in one way or another be a powerful weapon to fight corruption. These are the points that Subandri Simbolon emphasized in his presentation about a ritual of sharing meat as a value to prevent corruption in Toba Batak society.

Corruption is one of many problems that Indonesia as a nation faces. It is not only a law-related problem but also a cultural problem. As such, culture and the values it promotes could also in one way or another be a powerful weapon to fight corruption. These are the points that Subandri Simbolon emphasized in his presentation about a ritual of sharing meat as a value to prevent corruption in Toba Batak society.

To begin his presentation, Subandri showed a video about the process of sharing meat (membagi jambar) ritual at a wedding in Batak land. The video tells about how the meat is shared to certain groups of families as a symbol of acknowledgment and appreciation of their existence. In the video, family members circle around the meat as it is being cut into specific portions and one person lifts up a portion of the meat and calls out family names and gives the meat to them as other people can watch them clearly. The portion of the meat is given out based on the Batak system of family kinship called Dalinan No Tolu..

The process of sharing jambar is arranged in some parts. First, mengalap ari. Mengalap ari is the process of choosing a good day to begin the ritual. Secondly, the ritual begins by cutting the meat into certain portions while the audience can see it clearly. The leader will then share the meat to the people by calling their names. Here is the strong educational point by the sharing meat ritual happened. By sharing the meat and let everyone watch it, it teaches people about honesty, appreciation and acknowledgment of the relationships among families. The meat being shared in jambar juhut is a representative of “source of life”. By receiving the source of life, people are receiving blessings. Other than being a symbol of blessing, meat also a symbol of people’s rights. When they receive their portion, it means their existence and their rights to be involved and participate are being acknowledged.. Therefore, discussing blessing and rights in the Toba Batak context invites people to not be greedy and to say enough when it is enough.

Subandri highlighted the point that in the process of sharing meat there are strong and meaningful interpretations where the generations can learn about anti-corruption attitudes. Moreover he added, in the ritual of jambar juhut there is a strong relational concept shows that humans are connected to each other. Because this cultural conception is to some extent closer to Batak Toba people’s daily lives than the abstract legal definitions of fairness and government laws, Subandri argued that it can be more effective and powerful to turn people from corruption. In a relational framework, corruption is an activity that is detrimental because it violates and even negatesrelationshipsReflecting on this relational framework, Subandri revisited the meaning of sharing meat in Toba Batak tradition, arguing that it can be interpreted as an effort to strengthen relationships and promote honesty.

During the discussion session there were many fascinating questions that led people to deeper reflection on how humans sometimes are separated from their tradition to such an extent that they no longer think of it as a part of their existence or as a medium to learn from but merely as ceremony. One challenging question was about how, in many other traditions, instead of fulfilling the intention of renewing people’s understanding about relationships, this kind of ritual fails because it becomes a problem because of economic reasons. In order to answer that, Subandri encouraged the audience to think about the meat as a symbol of source of life: if it feels burdensome, people can replace the meat with something else like vegetables so that no one will be excluded. Subandri was also asked about the role of Christianity as the major religion in Toba land in this kind of ritual. He answered that while sometimes a priest or pastor is invited to begin the ceremony with prayer, there is not really any significant influence.

The discussion came to an end with a challenging invitation for all of us to find in our own culture the values that we can use to develop a cultural defense against corruption. Even though there is always to the possibility we might misinterpret the meaning of rituals such as this one, in the end, it is worth trying.

Negotiating Women’s Modesty in the Gendered Dynamics of Minang Society

M Rizal Abdi | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

The woman knelt down, supporting her body wrapped in traditional Minang cloth. She held a microphone that echoed her reedy singing and reverberated with the sound of flute from the man next to her. Suddenly, the sound of electronic music rushed in, disrupting the serene and heartbreaking melody with the upbeat dangdut rhythm. Still kneeling down and the female singer continued her sad singing with contradictory backsound as if it is synchronized to each other.

“Two decades ago, this wouldn’t be happening,” said Jennifer A. Fraser, Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology and Anthropology from Oberlin College, US. The contradictory yet fascinating scene above was shown during Fraser’s presentation in CRCS-ICRS Wednesday Forum on Wednesday, 8th August 2016. Entitling her presentation “Playing with Men: Female Singers, Porno Lyrics, and the Male Gaze in a Sumatran Vocal Genre”, Fraser shared her latest findings on Saluang Jo Dendang (literally flute with song), one of the Minangkabau music arts which is celebrated for its refined poetry based on allusions and its sad songs that induce tears in a listener. Using ethnographic research in West Sumatra dating from 1998, she tracked the gendered dynamics and increasingly sexualized interactions between female singers and their male audiences. In the 1960s, Saluang Jo Dendang was predominantly a male performance. Based on Minangkabau Islamic modesty, it was not considered appropriate for women to attend such an exclusively male event, let alone become the center of attention. The only possibility for a woman to participate as a performer was when her husband was the flute player. However, by the 1990’s, women started to displace men as the singer or pededang so that nowadays male pedendang are extremely rare. In fact, as one of male singers admitted, no one wants to listen to a male pedendang anymore.

Moreover, Fraser showed that there are shifting relations between the padendang and pagurau or attendees. In the past, with male singers, the pagurau usually listened to the song and fell into deep reflection on the lyrics. Sometimes the pagurau could also make song requests to the padendang directly. Nowadays, the pagurau usually tease or seduce the padendang by throwing some off-color jokes or requesting particular themes like divorce, asking for marriage, or other private matters. However, according to Fraser, the porno lyrics in the saluang performance refer to something different from the common understanding of pornography. Rather than explicitly using sexual vocabulary, most of lyrics categorized as porno by the audiences refer to anatomical description through allusion that tends to be not harmful but playful. For example,

Ali Jafar | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

The first CRCS/ICRS Wednesday Forum of 2016 welcomed Risnawati Utami, an activist for the human rights of persons with disabilities who recently played an important role in resolving a case concerning the rights of persons with disabilities in Bali to participate in their religion. . Together with her organization named OHANA (Organisasi Harapan Nusantara), she advocates for the human rights of persons with disabilities for shifting understanding about disabilities to ensure that persons with disabilities are treated as full and equal members of Indonesian society.

In her presentations, Risnawati said that “persons with disabilities constitute about 15% of the world’s population, meaning they are the largest minority in the world and mostly in the developing countries. Why persons with special needs required attention, it is because they are still discriminated against.” In religious model, Utami gave an example about persons with disabilities in Bali. Culturally in Bali, disabilities are understood as resulting from karma or actions done by the parents in their life or as punishment from bad behavior they did. When they have a disabled child, they will put their child in a different place, not in the main house. This happens not only in Bali, but also in many places.

Furthermore, Utami said that in Indonesia generally, the government looks on the person with disabilities as the object of charity, as a person who needs help and as object of development, it is kind of charity model happened. She told about disabled organizations which get a lot of rehabilitation programs, economic assistance, money, etc. ‘Can we see normality with disabilities?” said she. In medical model, Utami explained that she got polio when she was four, which has made her unable to walk. Her parents tried to make her normal. She completely disagrees with this model. It sees disability as not normal.

The term of disable is itself a problem. Utami explained that in Indonesia it is still common to use “penyandang cacat” which refers to a person with “special needs.” Meaning, we are still labelizing them. In the concept of humanity, we should not define people as “disabled,” but as “persons” because we are using concept of humanity in advocacy. According to the Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities, which Indonesia and most other countries have ratified, all people with disabilities can enjoy all the same human rights as everybody else, including religious freedom.

The third article of CRPD calls for the recognition of human rights and human diversity. Indonesia has not fulfilled this point, as can be seen from how LGBT (Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender) Indonesians cannot be religious leaders. A man who is gay and has a ‘disability’ , for example, cannot be a leader for other men in praying. He can be the leader only for woman.. Another related example is that according to marriage law in Indonesia, a man can be divorced or marry a second wife is his wife becomes disabled. Utami argued that this is discrimination against persons with disabilities.

Utami told a her story about when she was young. Her caretaker carried her to Mushola, and all the people there were asking why she was being carried. In Indonesia, public buildings are not designed to adequately accommodate persons with disabilities. In contrast, Risnawati told another story about a Muslim friend in England who is blind and can go everywhere with his seeing-eye dog, including the mosque. This situation would not be possible in Indonesia. Utami said that this is homework for Islamic leaders: can they learn to allow a blind Muslim into the mosque with a dog in order to pray?. Utami also told about her experience in America when a pastor invited her to go to his church, which was in a building is accessible for wheelchairs. She felt she could fully participate in life in America.

Utami continued that there is a custum, when a disable enters the temple and they fall down, the temple should be purified. It is quite debatable with religious organization in Bali. What Utami and her organization have done is creating mediation. In Indonesia generally, there are many deaf organizations in helping Muslim with disabilities. When they could not hear Khutbah (Jum’at prayer), they provide sign language for Muslim with disabilities. Utami mentioned UIN Yogyakarta’s mosque as an example about friendly institution over the person with disabilities. There is sign language during khutbah and the building was designed for disable also. Utami told how the building should be designed universally, it will reduce physical barrier over person with disabilities. Regarding to the freedom of religion, Utami said that it is about attitude and perspective, and how to eliminate ignorance and prejudice. It is also about how people like her can also have access to themosque.

In Discussion session, Samsul Ma’arif asked about the relation between religious freedom and universal design for persons with disabilities. It is because the way he understood religious freedom is about how we are not necessary to have similar though in religion. Utami responded the question saying that universal design is to accommodate people to come to that building. For Utami, the building is part of socialization, how people can get access to the accessible worship place like masques or church. Religious freedom is not about only about the same rights, but also about equal access.

Following Ma’arif, Mark Woodward asked about the most reason they rely on international organizations and Utami answered the Indonesian government responds to international pressure more than to lobbying from its own citizens. Thus the CRPD is an important tool for social change in Indonesia. Meta, a CRCS student, also asked about Utami’s opinion that religion also makes them as charity object? Utami answered that she has a quite liberal perspective, and sometimes still accepts the charity concept or uses several model on the time. “I advocated for persons with disabilities so they will not be underestimated.”

Editor: Greg Vanderbilt

Ali Jafar | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

In the beginning of her presentation, she drew a picture portraying goddesses of Nusantara (Indonesia Archipelago) on white board and told about narrative and myth over the mothers. She said that in humility paradigm of ecofeminism, all trees, animals, land and water have its own systems of thinking and communicating. How the stone whispers, why the water is raging, and how the land thinks. There is equality between human being and other non-human being. It was Dr. Phil. Dewi Candra Ningrum, the editor- in chief of Jurnal Perempuan (JP- Indonesian Feminist Journal) presenting in the CRCS’ Wednesday Forum on November 25th 2015.

Ali Jafar | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Maurisa, a CRCS alumna from the batch of 2011, presented her award-winning paper in Wednesday forum of CRCS-ICRS in 11th November 2015. Her paper entitled “The Rupture of Brotherhood, Understanding JI-Affiliated Group Over ISIS”, was awarded as best paper in IACIS (International Conference on Islamic Studies) in Manado, September. Maurisa was glad to share her paper with her younger batch. To all the audiences, Maurisa told that winning as best paper was not her high expectation, and it makes her proud.

The presentation began with Maurisa’s statement that the issue of ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) are quite to understand in relation to modern terrorism, because we always misread them and sometime we cannot differentiate between ISIS and Al-Qaeda. Maurisa continues her explanation that there are many groups in Iraq and Syria struggling for their power, terrorism is not single but many. ISIS also has supporters in Indonesia such as Jemaah Islamiyyah (JI-Islamic Group) which is considered as a big terrorist organization in Southeast Asia. This group (JI) has disappears from public consciousness, but actually its members have been spreading out. The most fascinating thing that she found is that JI in Indonesia. JI was separated into two, Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia (MMI) and Jama’ah Anshar at-Tauhid (JAT), and surprisingly JAT itself has internal conflict and divided into two; JAT and JAS (Jama’ah Anshar as Syari’ah).

Maurisa’s paper focused on questions about how does the conflict in Syria resonates with Jihadists in Indonesia, and how does political struggle within MMI show belief in a master narrative. Maurisa used Juergensmeyer’s perspective about cosmic war and the logic of religious violence. In the Juergensmeyer perspective, an ordinary conflict could become religious conflict when it is raised into cosmic level. One of the ways is demonization or Satan-ization of the enemy. In the context of Syria, the demon is Shia group which is blamed for chaotic situation within Sunni community. The master narrative was also about the same language. It is about sadness, it is about the sad feeling of being discriminated and persecuted by Shia.

According to Maurisa, not all jihadist groups support ISIS, indeed MMI was supporting Jabhat an-Nusra. The rupture of this affiliation was based on their differences in the perspective of takfirism (Apostasy). JAT and MMI have different perspectives in defining what Takfir Am (general apostasy) and takfir Muayyan (specific apostasy) is.

In seeing terrorist movements, although Maurisa saw that Jihad-ism is not monolithic, she revelas that there are five elements which are related each other. There are ideological resonance, strategic calculus, terrorist patron, escalation of conflict and the last is charismatic leadership. Terrorists also use social media, such as Facebook, Youtube and so on, to promote their propaganda, and as soft approach to other Muslims. Based on Maurisa’s research there are 50000 social media accounts to spread ISIS propaganda, but only 2000 are used to spread out propaganda. The most popular social media is Twitter, because a message can be retwited..

In the discussion session, Nida, a CRCS student asked about the current issues in which governments have banning Shi’a celebration in Indonesia, and whether there is any relation with ISIS, and how an Indonesian can be involved in the terrorism. Maurisa answered the question by explaining that Indonesia is about to change. It can be seen in Islamization created room for Islam in the public sphere. Indonesia is vulnerable since Wahabis and Iran have their political goals here and both want to establish their domination to spread out their agenda. Cases in Sampang, Madura, Pakistan and so on cannot be separated from international case. There are long story for transformation of Saudi and Iran. Our country is like something too. In talking about the entrance gate, Turkey is good entrance from Indonesia to go to Syria. If we see Turkey’s position is also questionable. They deny Isis, but they also support Isis.

Subandri also asked about the ways we interpret jihad are accessible. Therefore there are many interpretations of Jihad. That is what looks like for young Muslim now. Along with Subandri, Ruby also asked about the genealogy of Indonesian Jihadist movement. Like the connection between Indonesia and middle east that coming and potential realignment and the effect of JAT over ISIS.

In seeing connection and global phenomena, a relation between Islam and Middle East, Maurisa explained that in the United State for instance, there is relation if you wear jilbab, you are Muslim, and when you are Muslim, you are ISIS. “Here we can see the idea about securitization is like Islamophobia”, said Maurisa with showing slide about relation between Indonesia and Middle East. As she explained again “If we look at voice of Islam, we can see that there are solidarities for Syria. It is reported that medical mission in Indonesia, they have collected 1.6 million. For Syria suggesting support for the movement of mujahidin”. Maurisa also explained that globalization is the most responsible for this case. For example many Indonesia Muslims have easy access to Saudi, Iranian, Jihadist web, because of technology and so on. Young Indonesian have a lot of curiosity and they don’t ask to other.

In responding the interpretation of jihad, Maurisa gives a feedback, how do we interpret this? What makes cosmic war happen? And how to deal with them?. Maurisa began her explanation that in Islam, although there are many verses for killing, but it not necessary to do in violence. We have many steps in interpretation. There are many reasons for what make Muhammad approve of killing and in what context he did so. There are many possibilities to interpret jihad and there are many verses of good thing about Jihad. In talking about cosmic war, she said that “as long as we consider our enemy as Satan, or evil, meaning it is cosmic war”. At the end of discussion session, Maurisa concluded that the factor of jihad is not monolithic; there are many factors, even in ISIS and Al-Qaeda have different perspectives about jihad.

(Editor: Gregory Vanderbilt)

Ali Jafar | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

The discourse about “religion” “and” “science” has been long contested among scholars. Since the nineteenth century, religion and science have often been understood as in conflict with each other, science is human method for understanding nature using reason and religion relies on divine revelation. From different starting point, both religion and science have difficulties in finding common ground. But, starting from Ian Barbour, in the 1950s, a new discourse about the contemporary field of religion and science has proposed that integration is possible. Starting from this question at the Wednesday forum of CRCS/ICRS on 9th September 2015 , Zainal Abidin Bagir called for both side to re thinking the relation between science and religion.

The discourse about “religion” “and” “science” has been long contested among scholars. Since the nineteenth century, religion and science have often been understood as in conflict with each other, science is human method for understanding nature using reason and religion relies on divine revelation. From different starting point, both religion and science have difficulties in finding common ground. But, starting from Ian Barbour, in the 1950s, a new discourse about the contemporary field of religion and science has proposed that integration is possible. Starting from this question at the Wednesday forum of CRCS/ICRS on 9th September 2015 , Zainal Abidin Bagir called for both side to re thinking the relation between science and religion.

Bagir described the Barbourian discourse as sympathetic to religion, accepting of the basic theories and findings of modern science, and looking at scientists’ theories and theological beliefs to understand the relationship and its impact of the former on the latter. Barbour proposed a typology: conflict, independence, dialog- integration. In the conflict relation, we have to choose one. In the independent relation religion and science belong to separate world without contact. While in the dialog, we have to find similarities of them. The last is integration meaning that religion validate science each other.