Anang G. Alfian | CRCS | Class Journal

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

One of the exciting courses at CRCS is “Religion and Globalization”. Dr. Gregory Vanderbilt, the lecturer, has approached the study in an active and critical manner involving all the students in class activities. According to him, throughout the class students are expected to increase their capability to raise questions concerning the relation between religion and globalization as he himself prefer framing the class in series of discussions with world-wide ranges of topic.

As an American lecturer who has been working with CRCS since 2014 through Eastern Mennonite University, Virginia, he is a very well-experienced educator as he previously spent some years teaching in Japan. Moreover, his interest in following up the up-dated global issues including religious nuances, made him familiar with framing the methods of studying religion and globalization.

Global ethics is one of the topics we discussed in the class, the last material before the end of the class. Previously, we talked a lot about globalization as a phenomenon affecting religions as well as several religious responses toward globalization. Despite the supporters of globalization, many religions seem to fearfully reject it, some even proclaiming their resistance and becoming more radical.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Given the case of the famous forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an issue which is widely spread even in Japan (as well as Indonesia) is that Jews are the scary ghost behind a world conspiracy that can eventually make Japan as its next target. At least, this is what had affected Aum Shinrikyo, a radical religious sect, to declare war on Jews conspiracy and blaming them for brain-washing Japanese people. In 1995, this sect even became more radical and went wild killing tens of people in the Tokyo subway by poisoning them with deadly gas and injuring thousands of victims. Their resistance is, in fact, affected by global issues brought by high velocity of information through media and technology which successfully landed in the minds of traditional society. In this case, Aum Shinrikyo shows the same fundamentality as that of the terrible bombing of 9/11 in New York City by international terrorist network, Osama Bin Laden. In Rethinking Fundamentalism, a book we discussed in the class, we could see the influences of globalization toward religious community attitudes caused apparently by their fear, and their will for religious purification from distortion they see as brought by globalization.

Therefore, to foster the stabilization of the world order from war and disputes, it is necessary to rethink globalization in ways that are more ethical and friendly to the world. On the topic discussion of global ethics, we learned about attempts by world organizations like the United Nations in generating international agreements including the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Besides, other agreements such as the Cairo and Bangkok Declarations represent local voices which to some points define human rights differently.

The difference in worldviews among international actors is interesting because each organization tries to define a global value within their own relativities. Moreover, some theories think that UN Declaration on Human Right is a Western domination over other cultures without considering cultural relativities, including religions, each of which inherits different theological and structures while at the same time sharing common values like peace, humanity, equality, and justice.

World issues indeed became valuable perspective in this class. Students are meant to not only understand theories but also keep updating their knowledge on what is happening in the recent international world. While negative influences of globalization such as war, religious radicalization, and other world disputes were discussed in the class, there is also a hope for a global agreement and bright future by sharing noble values like cooperation, justice, human dignity, and peace on global scale. The existence of world organizations and religious representatives in fostering global ethics proves the progress made towards creating world peace. The duty of students, in this case, is to contribute academically to spreading such values without neglecting the variety of cultural and religious perspectives.

*The writer is CRCS’s student of the 2016 batch.

CRCS-UGM

Ilham Almujaddidy & A.S. Sudjatna | CRCS | Event Report

Dialog antaragama sebagai upaya penyelesaian konflik bukan hal yang mudah dilakukan. Tidak jarang terjadi, dialog yang dimaksudkan untuk menjembatani perbedaan dan meminimalisasi konflik tidak berjalan sesuai tujuan awal, atau bahkan kontraproduktif dan menimbulkan masalah baru.

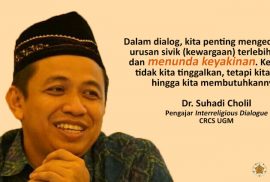

Dalam diskusi Forum Umar Kayam, Pusat Kebudayaan Koesnadi Hardjosoemantri (PKKH) UGM, pada Senin 25 Juli 2016, dosen CRCS Dr. Suhadi Cholil membahas persoalan ini. Dalam diskusi bertajuk “Menunda Keyakinan: Refleksi Membangun Pluralisme dari Bawah” itu, pengajar matakuliah Interreligious Dialogue di CRCS ini memberikan identifikasi-identifikasi penyebab dialog gagal mencapai tujuannya.

Pertama, kurangnya pemahaman substantif tentang fungsi dan metode dialog antaragama yang menyaratkan, antara lain, adanya saling percaya. Adanya praduga-praduga negatif terhadap mitra dialog dapat menimbulkan tiadanya saling percaya itu, dan pada gilirannya menjadi hambatan utama bagi efektivitas proses dialog.

Kedua, dialog antaragama yang semestinya menjadi interaksi untuk saling mengakomodasi masing-masing pihak yang terlibat, dalam prosesnya, malah terjebak dalam upaya untuk mendominasi.

Ketiga, dialog antaragama diandaikan sebagai penuntas konflik. Yang jarang dipahami, dialog dalam praksisnya tidak serta merta bisa menyelesaikan konflik. Beberapa konflik, apalagi konflik agama yang melibatkan klaim-klaim teologis yang sulit untuk dijembatani, tidak mudah dimediasi dengan dialog semata, dan karena itu memerlukan alternatif resolusi konflik yang lain.

Dengan menyadari hal-hal yang menghambat dialog antaragama itu, pemahaman yang tepat mengenai fungsi dan metode dialog antaragama bagi para pihak yang terlibat di dalamnya mutlak diperlukan, termasuk mensinergikan pengetahuan teoretis dan praksis.

Yang kerap menjadi problem di lapangan ialah banyak akademisi yang hanya fokus pada persoalan-persoalan teoretis atau teologis semata, namun abai pada ranah praktis. Sementara di sisi lain, ada banyak aktivis yang kurang reflektif secara teoretis maupun teologis, namun begitu aktif di pelbagai aktivitas dan advokasi perdamaian. Ketika kedua belah pihak ini terlibat dalam sebuah dialog, kerap kali muncul kesalahpahaman yang dapat memicu timbulnya permasalahan baru, dan karena itu kontraproduktif.

Hal lain untuk meminimalisasi hambatan dalam dialog antaragama ialah dengan mendudukkan isu teologis secara tepat. Tidak dapat dimungkiri, isu teologis merupakan isu sensitif, dan karena itu, jika tak hati-hati, justru dapat merusak proses dialog itu sendiri. Dalam proses dialog antaragama, isu teologis berada dalam ketegangan antara klaim eksklusifitas dan kehendak untuk menerima adanya keyakinan yang berbeda.

Dalam persoalan yang terakhir ini, Dr. Suhadi tidak mengusulkan untuk membuang eksklusivitas itu. Baginya, eksklusivitas itu sendiri tidak salah dalam dirinya sendiri. Ia akan menjadi masalah ketika tidak diterjemahkan dengan proporsi yang tepat di ruang publik. Banyak dari yang terlibat dalam proses dialog tidak membedakan antara ruang privat untuk ranah teologis dan ruang publik untuk pencarian titik temu guna menyelesaikan konflik. Karena kurangnya pemahaman untuk melokalisir klaim-klaim teologis pada ranah pikiran dan hati, dialog antaragama, alih-alih menjembatani perbedaan, justru rawan menjadi adu klaim teologis.

Merespons isu eksklusivitas teologis dalam dialog antaragama ini, Dr. Suhadi menawarkan gagasan bahwa untuk mengembangkan dialog antaragama yang lebih produktif, perspektif yang terbaik adalah dengan mendahulukan urusan sivik (kewargaan) dan menunda keyakinan. Hal ini tentu tidak berarti keyakinan ditinggalkan. Keyakinan ditunda, tidak dikedepankan, dan baru ditengok kembali ketika dibutuhkan dalam proses dialog.

*Laporan ini ditulis oleh mahasiswa CRCS, dan disunting oleh pengelola website.

Gregory Vanderbilt | CRCS UGM | Perspective

The kyai switched to English for just one sentence as he joined other village leaders in welcoming CRCS’s Eighth Diversity Management School or Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragaman (SPK) to the village of Mangundadi, 23 km west of Magelang, at the foot of Mt. Sumbing. Perhaps his choice was to honor the diversity present in this group—or that the chasm from ivory tower to mountain village had been bridged for an afternoon—as we tried to absorb the dance performance based on the carved reliefs of Borobudur we had just experienced. Though the village is 24km away from the 10th-century sacred site, and Muslim, it and its arts are part of the Ruwat-Rawat Festival movement that seeks to re-sacralize the great Buddhist monument from the disenchantment of the tourism industry and the weight of the busloads that climb it each day to snap selfies and admire in passing the craftsmanship of a millenium ago.

We were there because of the friendship with Ruwat-Rawat founder Pak Sucoro that has developed over the last year thanks to CRCS alumna Wilis Rengganiasih. Owner of the counter-narrative-producing Warung Info Jagad Cleguk across from the gates to the Borobudur parking lot and instigator of the eight-week festival each April-May, he had arranged an amazing afternoon for the excursion that has become an important change-of-page for SPK members after a week of ideas and passionate discussion. On the Saturday of the ten-day long school, the twenty-five members of SPK plus facilitators and friends departed by bus the school’s venue at the Disaster Oasis in Kaliurang, heading first to the warung at Borobudur to meet our guides and then heading another hour west from Magelang.

The road to the village of Mangundadi was too steep for our bus and so we were met at the main road by the pickups and motorcycles of the young men of the village. Having climbed on board, off we went to Mangundadi, the motorcycles revving their engines in a chorus of welcome. Afterwards SPK staffer Subandri admitted that he has now a tinge of positive feeling when he hears the youth gangs disrupt the city streets with their noisy machines, because what a welcome it was! When we reached the village, women lined the lane to shake our hands as we were ushered into one house to catch our breath, and then to process around the village’s new mosque with the genungan ritual mountain of vegetables, followed by the groups of performers, children, youth, adults, already in gorgeous costume and make-up. By the time we had feasted in another house, the performers were ready and, as the rain fell, they danced scenes from the stone reliefs. In the end, Pak Sucoro pulled some of us onto the stage to move with them and then they offered their salims and went back to their villages.

In the evening we returned to the Omah Semar retreat house near the monument-park for a discussion with Pak Sucoro about his vision of Borobudur as a universal spiritual heritage and as a place of spiritual significance for local culture, a place for Indonesian society to make a new choice, to live in harmony with God, nature, and each other. The Ruwat-Rawat has incorporated and re-ignited local traditions by focusing them on a global question, the question I asked the Advanced Study of Buddhism students who met Pak Sucoro back in May: who owns Borobudur? The next morning, walking across the lawns where his village once stood, we could see the stupa-monument in a new way.

In the evening we returned to the Omah Semar retreat house near the monument-park for a discussion with Pak Sucoro about his vision of Borobudur as a universal spiritual heritage and as a place of spiritual significance for local culture, a place for Indonesian society to make a new choice, to live in harmony with God, nature, and each other. The Ruwat-Rawat has incorporated and re-ignited local traditions by focusing them on a global question, the question I asked the Advanced Study of Buddhism students who met Pak Sucoro back in May: who owns Borobudur? The next morning, walking across the lawns where his village once stood, we could see the stupa-monument in a new way.

This was my third SPK since I came to CRCS in 2014. For me, it is an opportunity to meet the activists, academics, government workers, and media people who come to participate and see how change is happening across Indonesia. Each SPK may have its own character—this one, for example, was quicker to start singing than put on a mop of cringe-worthy joke telling—but the greater tone of excitement at being among others as serious of purpose and as ready to be challenged to greater intellectual depth is constant. The participants are excited by guest insights from Bob Hefner and Dewi Candraningrum but even more by the well-developed program from a core of facilitators devoted to teaching “civic pluralism” as a paradigm for just co-existence in the contexts of Indonesian diversity, one basing access in the three Re-‘s of recognition, representation, and redistribution, combined with thinking systematically about such core CRCS emphases as taking apart religion as lived and governed in Indonesia, digging into research for advocacy and putting into practice the theories and methods of conflict resolution. Equally important, they stay up late sharing their work, from teaching to preaching to activating NGOs to working conscientiously from inside government. Some know of the program because they have heard about CRCS while visiting or studying in Yogyakarta; others, following friends and co-workers who applied previously; and others still from searching online for “pluralism school” in order to serve better as religious and social leaders.

Visiting SPK alumni in their homeplaces—Jakarta, Aceh, West Sumatra, and Jambi, so far—has also shown me glimpses of grass-roots possibility across Indonesia. Trainings and workshops are regular features of Indonesian civil society, but it appears SPK leaves a more lasting impression on its participants. This is perhaps because of the intensity of their twelve days in the aptly named Disaster Oasis and perhaps because it challenges them more to take an intellectually grounded, hopeful framework to the places they are working and asks them to return with a research project, on how a pluralistically civil society is being made in soccer clubs and local studies movements and activism for gender (five from SPK-VIII work against domestic violence) and ethnic equality and film festivals and women’s economic literacy programs in villages and so on. In that way, the village kyai is right.

*The writer, Gregory Vanderbilt, is a lecturer at CRCS, teaching courses, among others, on religion and globalization; and advanced study of Christianity.

Jekonia Tarigan | CRCS UGM | SPK News

Pada hari keempat Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragamaan (SPK) angkatan ke-VIII tahun 2016 ini, tampak para peserta mulai dapat melihat muara dari upaya pendidikan yang dilakukan dalam SPK ini. Setelah beberapa hari bergaul dengan materi-materi yang menjadi landasan pembangunan kesadaran akan keberagaman dan penghargaan subjektifitas semua entitas dalam keberagaman, seperti teori identitas, reifikasi agama di Indonesia, dan lain sebagainya, para peserta dibawa ke ranah upaya mempraktikkan apa yang telah dipelajari.

Hal ini terwujud dalam topik “Advokasi Berbasis Riset” yang disampaikan oleh Kharisma Nugroho, seorang peneliti dan konsultan kebijakan-kebijakan publik dari KSI (Knowledge Sector Initiative) sebuah lembaga riset kerjasama Indonesia dan Australia yang bergerak dalam upaya mengangkat pengetahuan atau kearifan lokal dalam pembuatan kebijakan-kebijakan di tingkat daerah maupun nasional.

Dalam sesi ini disampaikan, semua peserta SPK perlu sampai pada titik di mana mereka terpanggil untuk melalukan sebuah upaya advokasi, yang secara sederhana dapat diartikan sebagai upaya memperjuangkan nilai-nilai atau ideal-ideal yang diyakini kebenarannya, misalnya mengadvokasi hak-hak masyarakat adat terhadap tanah adat mereka yang ingin dicaplok oleh perusahaan multinasional.

Namun fasilitator menekankan bahwa kerja advokasi bukanlah kerja otot (kerja keras) semata, sehingga basisnya bukan hanya emosi dan pemaksaan kehendak. Lebih dari itu, kerja advokasi adalah kerja otak (kerja cerdas), yang berarti bahwa orang-orang yang mengadvokasi harus tahu benar apa yang ia bela dan bagaimana cara membuat pembelaan dan perjuangannya itu berhasil.

Untuk itu, fasilitator menjelaskan ada tiga pengetahuan penting yang harus dimiliki oleh setiap peserta SPK, yakni: pertama, scientific knowledge, yaitu pengetahuan atau riset yang berbasis teori sebagaimana yang dapat diperoleh dalam kehidupan akademik di kampus; kedua, financial knowledge, yaitu pengetahuan atau riset yang didorong oleh lembaga-lembaga donor tertentu yang menghendaki adanya kajian tentang sebuah topik atau kejadian sebelum mereka memberikan bantuan, dll; dan yang ketiga, bureaucratic knowledge, yaitu pengetahuan terkait pemahaman pemerintah atas sebuah hal atau peristiwa yang ingin diadvokasi oleh satu lembaga swadaya masyarakat tertentu. Ini karena pemerintah mempunyai logikanya tersendiri terkait sebuah kebijakan yang akan diambil yang membuat mereka tidak hanya perlu fokus pada satu hal yang diadvokasi oleh satu LSM atau lembaga riset, tetapi juga melihat urgensi dan keberlangsungan pelaksanaan kebijakan yang akan dibuat nantinya.

Dalam SPK ini dijelaskan pula bahwa para advokator perlu menjaga kredibilitas, dengan menjaga kualitas riset. Fasilitator mengingatkan bahwa advokasi berbasis riset atau penelitian harus benar-benar teliti dan mencari terus hal-hal yang ada di balik fenomena, dan bukan hanya melihat kulit luarnya saja.

Fasilitator memberikan contoh, ada sebuah penelitian tentang program BPJS di tahun 2015 yang menyatakan bahwa pelaksanaan BPJS buruk, terjadi antrian panjang, masyarakat bingung dan kebutuhan perempuan kurang diperhatikan. Informasi ini jelas baik, namun tidak menjawab pertanyaan “apa yang menyebabkannya fenomena tersebut terjadi?” Secara sederhana, fasilitator kemudian membuat penelitian dengan memperhatikan data-data bidang kesehatan sepuluh tahun terakhir. Dari data yang dimiliki, fasilitator menemukan bahwa dalam sebuah penelitian dengan metode wawancara ditemukan bahwa masyarakat yang merasa sakit selama satu bulan hanya sekitar 25%, namun setelah adanya BPJS masyarakat menjadi lebih mudah mengakses layanan kesehatan, sehingga permintaan layanan kesehatan naik hingga 60%.

Sebelum adanya BPJS mungkin masyarakat tidak terlalu banyak mengakses layanan kesehatan dikarenakan biaya yang mahal, namun setelah ada BPJS permintaan layanan kesehatan naik hampir 100% sementara jumlah fasilitas kesehatan dan tenaga medis tidak bertambah secara signifikan. Dari hasi penelitian ini penting sekali untuk menemukan akar dari sebuah persoalan, sehingga saat dilakukan upaya advokasi isu yang dibahas adalah isu yang esensial dan dapat menjadi landasan bagi pengambilan kebijakan.

Hal lain yang juga sangat penting dari sebuah upaya advokasi adalah perubahan paradigma dari para pelaku advokasi. Advokasi tidak selalu soal mengubah undang-undang atau sebuah kebijakan. Lebih dari itu, bukti dari perubahan itu tidak pula selalu soal pendirian lembaga tingkat nasional sampai daerah yang dimaksudkan untuk menangani satu isu tertentu, sebab belum tentu perubahan undang-undang dan pendirian lembaga itu merupakan jaminan terjadinya perubahan. Bisa jadi ini justru adalah jebakan baru (institutional trap) yang menjadikan perubahan semakin lambat terjadi. Oleh karena itu, fasilitator mengingatkan ada beberapa aspek yang menandai terjadinya perubahan setelah upaya advokasi yaitu:

Meta Ose Ginting | CRCS | Wednesday Forum Report

Akhmad Akbar Susamto, active lecturer in in the Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) started his presentation in Wednesday Forum about Islamic and Western economics by explaining the background behind the academic discipline of Islamic economics. Islamic economics has been developed based on a belief that Islam’s worldview differs from that of Western capitalism. Islamic economics has its own perspectives and values related to how decisions are made. According to Susanto, the boundaries of Islamic economics as a social science or a discipline are closer to economics than to theology or to fiqh.

There is a strong impression telling that Islamic economics is in complete opposition with the Western conventional economics. Susanto argued that such an impression is wrong: although the Islamic worldview does differ from the worldview of Western capitalism, Islamic economics as an academic discipline was established to realize the Islamic worldview and can stand together with conventional economics established in the West. Each can benefit from the other.

Susanto introduced a new framework for Islamic economic analysis that lays a foundation for the complementarity between Islamic and conventional or Western economics. This new framework can resolve the dilemma faced by Muslim economists and help to establish Islamic academic disciplines alongside their Western peers.

This new framework introduced by UGM economists to define the scope and methodology of Islamic economics. It is called the Bulak Sumur framework. The name is taken from the name of the place where UGM is located. Based on the framework, an economy can be considered Islamic as long as it constitutes visions and methods which are consistent with Islamic worldview and it is able to help and guide societies to transform their economy towards the achievement of welfare as Islamic worldview dictates. To be Islamic requires not only separating the sacred and profane but being able to depict both the current state and the ideal state. Thus, the Bulaksumur Framework includes:

Abstract

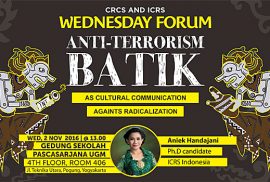

Acknowledged by UNESCO in 2009 as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, batik is produced through an introspective creative process in which the artist uncovers a truth and presents local wisdom and beauty. In this way, it can be an effective means to communicate symbols, ideas and messages about peace, respect and interreligious tolerance in order to counter the growing radicalism in Indonesian society. Aniek Handajani will present her new book Batik Antiterorisme Sebagai Media Komunikasi Upaya Kontra – Radikalisasi Melalui Pendidikan dan Budaya (co-written with Eri Ratmanto and published by UGM Press, 2016) as well as several works of batik she has commissioned in order to encourage public discussion about terrorism and peace.

Speaker

Aniek Handajani is a staff at the East Java provincial office of the Ministry of Education and an English lecturer at the Faculty of Education, Islamic University, Lamongan. She earned her Masters in Education at Flinders University in Australia and is an educator and activist for inter-religious peace. Currently, she is a Ph.D. candidate at Inter-Religious Studies (ICRS), UGM, researching terrorism and deradicalization.