Jika kolonialisme Eropa dulu datang membawa gold, glory, dan gospel; Indonesia tampaknya meluncurkan spin-off lokalnya: gold, glory, dan gus.

Perspective

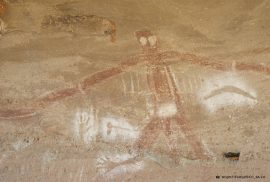

Lebih dari seribu salib kayu berwarna merah berdiri di pelbagai titik tanah ulayat suku Awyu di Boven Digoel, Papua Selatan. Salib itu bukan sekadar penanda wilayah ulayat suku Awyu, melainkan juga sebagai bahasa keagamaan dan kultural yang melindungi mereka dari ancaman rencana pembangunan perkebunan sawit.

Di samping mengandung unsur-unsur protektif yang dapat menurunkan gejala depresi, agama juga dekat dengan risiko-risiko tertentu yang berpotensi memperburuk kesehatan mental

Masuknya kekristenan di Asmat tidak hanya membawa pesan keselamatan rohani, tetapi juga membawa sistem makna baru yang berpotensi memutus ingatan spiritual.

Bagaimana bila pemuka agama yang tadinya berperan sebagai penjaga moral justru dianggap sebagai ancaman terhadap moral masyarakat?

Bagi para perempuan Sudan, mungkin ada lebih banyak harapan bagi mereka ketika bertemu langsung dengan Tuhan daripada menderita dan menyerah kepada perbuatan biadab pemerkosa.

Masyarakat Adat Bayan telah lama dikunci oleh label kolonial sebagai “Islam Wetu Telu”. Bahkan istilah ini kerap direduksi menjadi “Islam Waktu Tiga”, yakni anggapan keliru bahwa mereka hanya salat tiga kali sehari.

Makco bukan saja fenomena global yang terabadikan sebagai warisan dunia, melainkan juga merupakan fenomena kosmopolit yang selalu direproduksi dan mewarnai kebudayaan lokal. Kirab Makco telah membuka ruang artikulasi kosmopolitanisme di Indonesia

Agama tidak mengekang apa yang seharusnya kita lepaskan. Agama ada sebagai pelipur saat kita harus bersabar dalam berjihad menentang tirani dengan berbagai cara dan kemampuan kita, termasuk, dengan energi marah yang menggerakan kita

Mengingat masih kuatnya kontrol negara terhadap kehidupan beragama atau berkeyakinan, pergeseran paradigma dari kerukunan dan moderasi beragama ke kebebasan beragama atau berkeyakinan tampaknya masih perlu menempuh perjalanan jauh dan berliku.

Sebagai bagian dari hak asasi manusia (HAM), kebebasan beragama atau berkeyakinan (KBB) selalu terhubung dengan hak-hak yang lain. Oleh karena itu, pelanggaran terhadap KBB seringkali berdampak pada pelanggaran hak-hak yang lain.

Alih-alih sebuah pengetahuan takhayul tak berdasar, Maquwoli adalah sebuah gagasan dan praktek hidup yang sangat kontekstual secara sosial-ekologis, yang berakar dari analisis empirik yang mendalam

Keberadaan delik terkait agama atau kepercayaan dalam Kitab Undang-Undang Hukum Pidana (KUHP) 2023 membawa angin segar bagi kebebasan beragama atau berkeyakinan (KBB) di Indonesia. Namun, hukum pidana tak selalu menjadi solusi atas kasus intoleransi dan diskriminasi yang terjadi.

Di mata pihak-pihak intoleran, teks-teks hukum “yang tidak jelas” dapat diterjemahkan secara intoleran juga.

Pemerintah dengan percaya diri menyatakan bahwa Kitab Undang-Undang Hukum Pidana (KUHP) baru yang disahkan 2023 silam memberikan jaminan kehidupan beragama atau berkeyakinan (KBB) yang lebih baik. Pasal 300–305 KUHP 2023 yang bertajuk Tindak Pidana terhadap Agama, Kepercayaan, dan Kehidupan Beragama atau Kepercayaan secara khusus mengatur delik keagamaan. Namun, pasal-pasal tersebut rupanya berpotensi kuat menjadi “pasal karet” yang rentan untuk ditafsirkan menurut kepentingan pihak-pihak intoleran. Jika demikian, perlindungan terhadap masyarakat yang berasal dari kelompok-kelompok rentan keagamaan akan makin terciderai.

Ketidakjelasan hukum dapat berakibat pada penegakan hukum yang diskriminatif. Ketidakjelasan ini kerap bermuara pada ketidakjelasan rumusan hukum itu sendiri. Akibatnya, hukum yang harusnya menjadi pelindung, malah jadi perundung.

Meskipun Indonesia telah merdeka secara fisik, konstruksi cisgender ala kolonial masih berkembang hingga saat ini. Ajaran keagamaan yang kian patriarkis turut merawatnya sampai kini.

Semasa kolonial, pemerintah Hindia Belanda menerapkan politik agama dengan menjadikan ajaran di luar Kristen, Katolik, dan Islam sebagai geen goddienst atau nonagama (Yulianti, 2022). Politik agama tidak hanya memaksa masyarakat adat untuk mengikuti ajaran agama-agama yang diakui pemerintah, tetapi juga konstruksi gender yang dibawanya. Contohnya bisa kita lihat pada kasus komunitas bissu. Pemerintah kolonial menjadikan tradisi dan identitas seksual komunitas bissu sebagai “amoral”. Alhasil, komunitas tersebut menjadi objek utama konversi agama (Gouda, 1995).

Menelusuri Kembali Jejak Marginalisasi Gender di Indonesia

Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer – 07 Januari 2025

Perempuan dan lelaki memang memiliki tubuh biologis yang berbeda. Namun, perbedaan ini tidak serta-merta secara alamiah menggariskan peran dan ekspresi gendernya di kebudayaan masyarakat tertentu.

Banyak ahli sejarah dan antropolog berpendapat bahwa kebudayaan patriarki bermula sejak manusia masih dalam peradaban berburu dan meramu. Salah satu yang menonjol ialah antropolog Richard B. Lee dan Irven DeVore. Keduanya menginisiasi simposium internasional terkait fase peradaban manusia tersebut dan menghasilkan kumpulan esai berjudul Man the Hunter (1968). Di antara simpulannya, masyarakat peradaban berburu dan meramu menentukan peran gender berdasarkan fitur biologis laki-laki dan perempuan. Perempuan, pemilik rahim dan payudara, berperan menjaga keberlangsungan populasi komunitas dan mengurusi domestik. Sementara laki-laki, dengan fisik yang lebih sederhana dan berpenis, menjadi penyedia keberlangsungan komunitas.

Ketika organisasi keagamaan menerima pengelolaan tambang, masih ada harapan kepedulian lingkungan yang terus bertumbuh

Dinamika Keagamaan Talang Mamak: Sebuah Catatan Lapangan

Miftha Khalil Muflih – 10 Juni 2024

“Kau siapo, kok baru tetengok di siko?”

Pertanyaan itu meluncur dari salah seorang penjual di salah satu pasar yang ada di Kabupaten Tebo, Provinsi Jambi. Melihat ada orang yang tampak asing, sang penjual sedang bertanya siapa gerangan saya. Dengan penduduk yang terhitung sedikit, masyarakat memang akan mudah untuk menandai orang asing yang datang ke lingkungan tersebut. Merespon pertanyaan tersebut, saya mengenalkan diri sebagai mahasiswa Jogja yang sedang magang dan riset di masyarakat adat Talang Mamak. “Oh Talang Mamak yo, mereka di sano animisme kan, yang menyembah sungai, pohon,” tukasnya. Salah seorang masyarakat Talang Mamak yang membersamai saya lalu menyahut, “Awak la punyo agama, Kristen agama awak”. Ia merespons sambil tersenyum kecut.

Memperluas Makna Pentakosta Melalui Unduh-Unduh

Rezza Prasetyo Setiawan, Eikel Karunia Ginting – 14 Mei 2024

Ada banyak cara umat kristiani di Indonesia merayakan Pentakosta, hari ke-50 masa Paskah yang menjadi momen turunnya Roh Kudus, salah satunya dengan ritual unduh-unduh. Tradisi akulturasi umat Kristen yang tinggal di kawasan agraris ini biasanya dilaksanakan pada musim panen padi. Namun, Gereja Kristen Jawa Tengah Utara (GKJTU) Bukit Hermon di Desa Kopeng, Kabupaten Semarang, Jawa Tengah, melaksanakan ritual unduh-unduh untuk menyambut momen Pentakosta. Keberadaan ritual unduh-unduh di desa ini sempat terhenti puluhan tahun karena anggapan sesat dari misi ajaran kristen yang menolak kebudayaan. Upaya revitalisasi pun muncul pada 2019 seiring dengan kondisi lingkungan desa yang semakin rusak.

Interseksionalitas Akbattasa Jera dalam Masyarakat Ammatoa

Zulfikarni Bakri – 03 Mei 2024

Pemakaman di Dusun Benteng, Tanah Toa, Kajang penuh dengan susunan daun sirih, pinang, dan tembakau, serta beberapa bambu muda berisi tuak. Perempuan maupun laki-laki berpakaian serba hitam saling bertegur sapa bersama sanak keluarga yang baru pulang ke kampung halaman jelang lebaran. Pada 4 April 2024, tepat hari ke-23 Ramadan, masyarakat Ammatoa Kajang yang tinggal di Kawasan Adat Dalam dan Luar melakukan tradisi akbattasa jera.

Akbattasa jera berarti ‘membersihkan makam’ (Maarif, 2012). Ritual ini dilakukan sekali dalam satu tahun seminggu menjelang lebaran. Menurut Ammatoa (pemangku adat tertinggi), akbattasa jera ini ada dua macam yaitu akbattasa jera di hutan keramat dan akbattasa jera ke semua pemakaman di kawasan Kajang. Pada hari ke-22 Ramadan, Ammatoa bersama beberapa orang kepercayaannya terlebih dahulu mengunjungi makam di Jera Tunggala yang berada dalam hutan karrasayya (hutan keramat). Bagi masyarakat Ammatoa, kuburan ini tidak hanya menjadi simbol makam manusia pertama (Ammatoa pertama), tetapi juga situs peninggalan leluhur dari berbagai macam ras di bumi sekaligus merupakan tempat manusia pertama kali bermukim. Tidak semua orang dapat mengikuti ziarah ke area hutan adat ini. Di samping Ammatoa, hanya orang-orang tua dengan ilmu spiritual tinggi yang dapat turut serta dalam ritual tersebut. Akbattasa jera di Jera Tunggala ini membuka semua aktivitas ziarah makam di hari-hari selanjutnya oleh masyarakat Ammatoa Kajang. Ritual tersebut kemudian disusul dengan baca doang (membaca doa) di rumah masing-masing.

Kasus penelantaran bongpay di Semarang memancing pertanyaan, masihkah pemakaman ala tradisi Tionghoa menjadi urusan penting dalam kehidupan keagamaan orang Tionghoa?

Misa Imlek kerap dianggap sebagai simbol akomodasi gereja Katolik terhadap identitas ketionghoaan. Di sisi lain, tak sedikit umat dan pemuka Katolik yang mempertanyakan keberadaannya.

Kabupaten Sumba Timur ialah satu-satunya kabupaten yang mengatur secara resmi eksistensi pendidikan kepercayaan melalui regulasi daerah. Sebagai program rintisan, keberadaannya patut diapresiasi sekaligus dicermati agar tidak sekadar memperpanjang kolonialisasi agama lewat pendidikan.

Menggayuh Kebangsaan dalam Keimanan:

Rabu Abu, Pemilu, dan Politik Identitas

Teresa Astrid Salsabila – 14 Februari 2024

“Karena itu perlu saya tegaskan bahwa kita semua yang sudah memiliki hak pilih dan sudah terdaftar sebagai pemilih tetap, wajib datang ke tempat pemungutan suara (TPS) dan dengan bebas penuh sukacita memberikan hak pilih atau hak suara kita. Jangan Golput!”

Itulah sepenggal pesan Mgr. Robertus Rubiyatmoko, Uskup Agung Semarang, dalam Surat Gembala menyongsong masa Prapaskah. Selama 40 hari sebelum Paskah, umat Katolik menghayati sengsara Yesus Kristus dengan berpuasa, berpantang, dan bertobat. Momen Prapaskah tahun ini cukup istimewa. Hari pertama Prapaskah jatuh pada 14 Februari 2024. Ini artinya hari raya Rabu Abu bersamaan dengan dua momen penting lainnya yaitu Hari Kasih Sayang dan Pemilihan Umum 2024. Sebagai bagian dari masyarakat Indonesia, Gereja Katolik turut merespons pesta demokrasi ini dengan berbagai cara.

Luka sejarah tak lantas menyurutkan umat Konghucu untuk mengekspresikan religiusitasnya di ruang publik. Meski mengalami kemerosotan jumlah persentase umat, perjalanan agama Konghucu pasca-Orde Baru tidak sesuram proyeksi data itu

Queer Nyantri, Ga Bahaya Ta?

Nanda Tsani – 27 Januari 2024

Queer muslim ngaji kitab, salat, zikir berjamaah, ziarah kubur, menabuh rebana, dan berselawat kepada Rasulullah. Namun, tetap saja muncul pertanyaan, apakah keberagamaan queer muslim ala Nusantara ini valid dalam Islam?

Jumat, 20 Oktober 2023. Waktu menunjukkan pukul 19:52 saat kereta kami berhenti di Stasiun Cirebon. Saya bersama rombongan santri kilat dari Yogyakarta akan menuju Kampus Transformatif Pondok Pesantren Luhur Manhajiy Fahmina. Bersama kontingen lain dari berbagai kota di Indonesia, kami akan mengikuti Nyantri Kilat, sebuah program yang diinisiasi IQAMAH (Indonesian Queer Muslims and Allies), di pesantren ini selama 2 hari.

Agama, Kekerasan Seksual, dan Ketidakadilan Epistemik

Yohanes Babtista Lemuel Christandi – 19 Januari 2024

Keterkaitan agama dan ketidakadilan tidak selamanya dalam relasi oposisi. Agama memang dapat menjadi landasan untuk memberantas ketidakadilan, tetapi nyatanya agama juga merupakan tanah subur terjadinya ketidakadilan.

Selama dua tahun laporan Monthly Update on Religious Issue in Indonesia (MURII), ada satu isu keagamaan yang hampir muncul di tiap edisi yaitu kekerasan seksual di institusi pendidikan berbasis keagamaan. Fakta ironis ini menunjukkan bahwa agama bukanlah tempat yang steril dari ketidakadilan. Malah, ketidakadilan kerap menyamar dalam bungkus narasi keagamaan atau bersembunyi di balik ketiak otoritas keagamaan sehingga sukar dikenali. Miranda Fricker dalam bukunya Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing (2007) menyebut fenomena semacam ini sebagai ketidakadilan epistemik.

Mengapa Mati Pun Harus Beragama?

Teresa Astrid Salsabila – 1 Desember 2023

Setiap kematian di Indonesia sulit untuk lepas dari pengaruh agama. Ia mengikat siapa pun hingga ke ujung hayat: tak peduli apa pun yang ia yakini.

Hari itu adalah hari yang muram bagi saya. Orang yang saya kenal dan kasihi wafat. Berpisah dengan yang terkasih karena kematian selalu menyisakan kesedihan mendalam. Namun, duka kali ini berbeda. Inilah pertama kalinya saya terlibat mengurusi prosesi kematian seseorang yang menyatakan diri tidak beragama. Jika merujuk pada kartu identitas, tidak ada agama yang tercantum di sana karena mendiang tercatat sebagai warga negara asing. Pasangannya juga meminta prosesi tersebut tidak menggunakan unsur agama apa pun sebagai bentuk penghormatan atas pilihan hidupnya. Di sinilah dilema dimulai.

Sebuah Jalan untuk Pengakuan:

Negosiasi dan Rekognisi dalam Festival Cheng Ho

Refan Aditya – 19 Oktober 2023

Tambur ditabuh, gemuruh perkusi memenuhi Kelenteng Tay Kak Sie dan memecah langit pecinan Semarang 19 Agustus 2023. Orang-orang mulai memadati halaman kelenteng. Beberapa kelompok seni Tionghoa sudah bersiap sejak dini hari. Mereka akan mengarak arca (kong co) Laksamana Cheng Ho atau Sam Poo Tay Djien menuju Kelenteng Sam Poo Kong. Arak-arakan ini, yang juga disebut Kirab Sam Poo, merupakan rangkaian acara “Festival Cheng Ho 2023”. Kirab Sam Poo dirayakan setiap tanggal 29 bulan enam penanggalan Imlek sebagai peringatan ke-618 kedatangan Laksamana Cheng Ho ke Semarang.

Silek di Rantau:

Membela Diri, Merawat Tradisi

Bibi Suprianto – 29 September 2023

Beberapa pekan silam kita dihebohkan dengan bentrok antarperguruan silat Indonesia di Taiwan yang berujung pada korban meninggal dunia. Fakta memalukan sekaligus memilukan ini secara tidak langsung membentuk citra negatif pencak silat sebagai ajang baku hantam. Padahal, bagi beberapa masyarakat adat di Indonesia, pencak silat bukan sekadar seni bela diri, melainkan bagian dari identitas dan tradisi.

Silat, Rantau, dan Minangkabau

Salah satu kelompok masyarakat yang dekat dengan tradisi silat ialah Minangkabau di Sumatra Barat. Dalam tradisi Minangkabau, silat—yang disebut dengan silek—erat kaitannya dengan tradisi merantau. Silek merupakan bekal wajib bagi para lelaki yang akan meninggalkan kampung halamannya untuk mencari pengalaman hidup. Sebelum merantau, mereka harus belajar silek untuk membela diri dan melatih jasmani. Dalam tradisi Minangkabau, silek berbeda dengan mancak kendati bentuk gerakannya hampir serupa. Gerakan silek cenderung melumpuhkan lawan, sementara gerakan mancak untuk kepentingan hiburan dan pertunjukan seni. Sebagai bagian dari tradisi, silek diajarkan dan diwariskan turun-temurun melalui guru yang disebut tuo silek. Para pemuda Minang ini berlatih silek di surau biasanya saat malam hari sebelum jam 12 malam, ada juga beberapa latihan yang dilakukan di tengah terik siang. Pengajaran silek selalu dibarengi dengan pengajaran agama agar para pesilat tidak menyalahgunakan ilmu yang ia pelajari. Berbekal silek, para pemuda Minang diharapkan punya kemampuan untuk menjaga dirinya (panjago diri) di tanah perantauan.

Melampaui Materialisme Kultural:

Relasi Anjing dan Manusia dalam Perspektif Orang Huaulu

Vikry Reinaldo Paais – 20 September 2023

Pernah nonton film Hachiko: A Dog’s Story? Film yang terinspirasi dari kisah nyata ini bercerita tentang seekor anjing bernama Hachiko di Jepang yang sangat setia kepada tuannya. Hachiko akan selalu pergi ke statsiun kereta untuk menanti kedatangan tuannya yang sehabis bekerja. Akhir film ini begitu mengharukan. Hachiko yang tidak tahu bahwa tuannya telah lama meninggal terus menanti kedatangan sang tuan di stasiun kereta. Hachiko terus menanti sampai akhirnya meninggal di tempat yang sama ia biasa menunggu tuannya. Saya sendiri sampai meneteskan air mata menonton akhir kisah Hachiko. Saking fenomenalnya kisah tersebut, orang Jepang sampai membuatkan patung anjing di depan stasiun Shibuya untuk mengenangnya. Kisah Hachiko adalah contoh relasi manusia dan hewan yang sangat intim.

Analisis Wacana Kritis: Ilmu Sosial Kuantum?

Rezza Prasetyo Setiawan – 21 Agustus 2023

“Saya itu tidak ada—yang ada hanya wacana.”

Ujaran itu diulang hampir setiap minggu oleh Prof. Frans Wijsen, dosen pengampu mata kuliah Discursive Study of Religion (Studi Diskursif tentang Agama). Namun, yang justru kerap terlintas dalam pikiran saya malah Prinsip Ketidakpastian Heisenberg, salah satu prinsip yang populer dan berpengaruh dalam diskursus fisika kuantum.

Kesannya memang tidak nyambung. Akan tetapi, tidak sedikit akademisi yang sudah membangun jembatan pengetahuan antara fisika kuantum dan ilmu-ilmu sosial (social sciences). Karen Barad dalam bukunya, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (2007), menggunakan prinsip-prinsip fisika kuantum seperti difraksi dan keterikatan kuantum (quantum entanglement) untuk melawan esensialisme dalam pola pikir modern. Dalam artikel lain, Ben Klemens (2020) menyoroti keterbatasan ilmu sosial dalam mengukur aspek-aspek yang harus diperhatikan sehingga model-model penelitian tidak akan pernah sepenuhnya tepat. Dari sini, senyampang prinsip ketidakpastian dalam fisika kuantum menemukan kesejajarannya dengan ranah keilmuan sosial.

Puja Waisak Lintas Negeri:

Tradisi Thudong, Waisak, dan Umat Buddha Indonesia

Candra Dvi Jayanti – 04 Juni 2023

“Berkelanalah, O, Para bhikkhu, demi kesejahteraan banyak makhluk, demi kebahagiaan banyak makhluk, demi belas kasih terhadap dunia, demi kebaikan, kesejahteraan, dan kebahagiaan para dewa dan manusia. …” (Dutiyamārapāsa Sutta; Samyutta Nikaya 4.5)

Menjelang peringatan hari raya Waisak 2023, masyarakat Indonesia begitu antusias menyambut kehadiran rombongan istimewa para bhikkhu dari Thailand yang berjalan kaki ribuan kilometer dalam sebuah perjalanan spiritual menuju Candi Borobudur. Istilah bhikkhu thudong kemudian akrab di telinga masyarakat setelah perilisan berbagai berita di media massa dan media sosial yang mewarnai sepanjang perjalanan para bhikkhu tersebut. Euforia ini terasa di tiap kota yang dilewati oleh para bhikkhu ini. Masyarakat dari berbagai lapisan dan golongan berjejer di pinggir jalan untuk melihat sekaligus menyemangati 32 bhikkhu ini. Keberadaan mereka kerap menjadi simbol aksi toleransi umat beragama di Indonesia. Di tengah euforia tersebut, bagi umat Buddha di Indonesia sendiri, perjalanan bhikkhu thudong ke Borobudur menjadi momentum untuk memaknai kembali hari trisuci Waisak dan mendalami ajaran agama.

Indonesia sebagai Ketua ASEAN 2023: Mempromosikan Harmoni Antaragama di Wilayah ASEAN

Harry Myo Lin – 26 Mei 2023

Seiring terpilihnya Indonesia sebagai ketua ASEAN 2023, Indonesia memiliki peluang unik untuk memperkenalkan sejarahnya yang kaya akan keragaman agama serta keberhasilannya dalam mengelola kerukunan antarumat beragama.

Sebagaimana Indonesia, kawasan ASEAN adalah permadani dengan beragam keyakinan dan praktik keagamaan. Ini dapat kita lihat dari negara-negara yang mayoritas penduduknya beragama Buddha seperti Thailand dan Myanmar; negara-negara mayoritas Islam seperti Indonesia, Malaysia dan Brunei; dan negara-negara mayoritas Kristen seperti Filipina; serta hampir semua negara ASEAN memiliki populasi minoritas yang signifikan seperti Hindu, Sikh, Yahudi, Baha’i, dan tradisi-tradisi agama lokal. Kemajemukan agama ini menjadi tantangan sekaligus peluang bagi kohesi dan stabilitas regional. Menyadari keberagaman ini, Indonesia dapat memainkan peran penting dalam mempromosikan kerukunan antarumat beragama sebagai Ketua ASEAN pada tahun 2023.

Menjadi Wong Gunungkidul Bersama Komunitas Resan

Ronald Adam dan Jonathan D. Smith – 17 April 2023

Di tengah terkikisnya budaya dan tradisi lokal yang beriringan dengan krisis lingkungan, suatu kelompok di Gunungkidul bernama Komunitas Resan mencoba menguatkan kembali identitas lokal mereka sebagai “orang Gunungkidul”.

Wilayah Gunungkidul, D.I. Yogyakarta, seringkali mendapatkan stigma peyoratif sebagai tempat miskin di pedalaman yang selalu dilanda kekeringan, marginal, dan banyak kasus orang bunuh diri (pulung gantung). Di samping itu, tradisi budaya dan kearifan lokal Gunungkidul dalam memuliakan alam sering dipandang sebagai mistis atau klenik. Tak jarang, sebagian kelompok mencap mereka sebagai “penyembah pohon”.

Catatan dari Negeri Huaulu, Maluku

Vikry Reinaldo Paais – 6 April 2023

Pulau Seram adalah pulau terbesar di Provinsi Maluku. Tidak diketahui pasti mengapa pulau ini disebut Pulau Seram. Namun, yang pasti, istilah “Seram” tidak ada kaitannya dengan angker. Dalam narasi lokal, Pulau Seram dikenal sebagai Nusa Ina alias ‘Pulau Ibu’. Jika ditanya dari mana asal-usul manusia, orang Seram—dan beberapa pulau di sekitarnya—dengan bangga akan menyebut Nunusaku dan juga Supa Maraina sebagai tempat asal mula kehidupan manusia. Keduanya—dalam kosmogini orang Maluku—terletak di Pulau Seram. Dengan kata lain, Pulau Seram-lah tempat lahir manusia pertama. Dari pulau ini, masyarakat Maluku kemudian terpencar ke pulau-pulau di sekitarnya dan mendirikan negeri-negeri. Narasi ini yang melegitimasi Seram sebagai tasalsul nenek moyang orang Maluku. Seram dianggap sebagai “ibu” yang melahirkan peradaban, adat, dan kebudayaan.

“Beragama” dengan Sepak Bola

Maryolanda Zaini – 4 April 2023

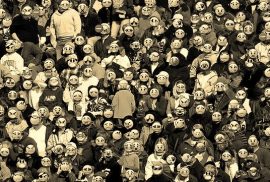

Sepak bola telah menjadi salah satu tontonan olahraga terpopuler di planet ini. Mulai dari perhelatan Piala Dunia hingga Liga Inggris, miliaran penonton dari seluruh dunia menyaksikan tim favoritnya berkompetisi di lapangan. FIFA mencatat setidaknya 1,5 miliar orang menonton final Piala Dunia 2022. Sepak bola memang tidak hanya menawarkan atraksi adu olah bola di lapangan, tetapi juga menyediakan rangkaian ritual dan euforia kebersamaan bagi para penontonnya: mulai dari berjamaah datang ke stadion, berkumpul bersama dengan seragam klub/federasi, hingga kompak bernyanyi mengobarkan yel-yel bagi tim kesayangannya. Di sinilah sepak bola dan agama beririsan.

Hewan sebagai Warga Negara: Refleksi atas Kewargaan Ekologis

Andi Alfian – 24 Maret 2023

Beberapa waktu silam, jagat media sosial dihebohkan oleh satu video aksi Afni Zulkifli, seorang Tenaga Ahli dari Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan (KLHK) Provinsi Riau, yang membela kawanan gajah dari tuntutan warga. Pasalnya, warga merasa terganggu karena para gajah tersebut melintasi area pemukiman mereka. Di video itu, Afni Zulkifli justru tegas mengingatkan warga bahwa bukan kawanan gajahlah yang melintasi kebun para warga, “Tapi desa dan kebun bapak-bapak yang masuk ke rumah gajah!” Selama puluhan tahun, kawanan gajah secara naluriah selalu melewati jalur yang sama, sementara pembangunan kawasan hunian manusia dan perkebunan terus berkembang.

Masyarakat Adat dan Ideologi Pembangunan yang Gagal

Andi Alfian – 20 Februari 2023

Masyarakat adat adalah salah satu komunitas yang telah (dan terus akan) menjadi sasaran berbagai program pembangunan di Indonesia, baik dari institusi pemerintah maupun oleh lembaga nonpemerintahan. Berdasarkan catatan Christopher R. Duncan, dalam Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities (2008), program pembangunan pemerintah Indonesia yang menyasar masyarakat adat—atau dalam bahasa Duncan, “isolated tribes” atau “isolated communities”—mulai marak sejak 1970-an. Meski berbagai persoalan dan kritik terus bermunculan, proyek pembangunan tersebut terus berlanjut hingga hari ini.

Idealnya Borobudur merupakan kawasan yang subur dan terhindar dari krisis ekologi. Namun, krisis air kerap melanda desa-desa di sekitarnya saat musim kemarau. Masyarakat desa sekitar Borobudur berupaya merawat sumber mata air yang tersisa melalui jalan tradisi.

Kitab Undang-undang Hukum Pidana (KUHP) baru yang disahkan pada awal Januari 2023 telah memancing kontroversi di media dalam dan luar negeri. Salah satu perubahan yang belum banyak dibahas adalah pasal-pasal terkait agama. Dalam tulisannya di harian Kompas (5 Januari 2023), Rumadi Ahmad menunjukkan adanya beberapa kemajuan. Namun, tak sedikit media internasional yang justru mengkritik keras dan mengklaim adanya pasal-pasal bermasalah, termasuk perluasan pasal tentang kriminalisasi blasphemy (penodaan agama), bahkan apostasy (meninggalkan agama).

Konversi Agama dalam Tarik Ulur Universalitas dan Relativitas HAM

Vikry Reinaldo Paais – 25 Oktober 2022

Praktik konversi agama atau berpindah agama cenderung menjadi isu sensasional dan hangat diperbincangkan. Fenomena ini terjadi di setiap kalangan, entah itu figur publik—seperti para artis dan elite politik, masyarakat awam, terlebih lagi jika dilakukan oleh petinggi agama. Tak pelak, isu konversi agama menuai pro dan kontra. Beberapa mendukungnya atas nama hak asasi manusia (HAM). Ada pula yang menampiknya atas dalil ketidaktaatan dan pembangkangan terhadap ajaran agama. Padahal, tak bisa dimungkiri, konversi agama akan selalu ada sepanjang agama-agama itu eksis.

Di Balik Jilbabmu: Pergulatan Ekspresi, Represi, dan Otoritas Diri

Linda Zuarnum – 06 Oktober 2022

September 2022 lalu, media dihebohkan dengan aksi bakar jilbab perempuan Iran sebagai bentuk protes terhadap tindakan polisi moralitas di Iran yang mengakibatkan Mahsa Amini meninggal. Amini, yang juga dikenal dengan Zhina Amini (ژینا امینی), sedang berlibur ke Tehran saat ditangkap dan dianiaya oleh polisi moral. Perempuan asal Saqez, Khurdistan, itu dianggap tidak menggunakan jilbab sebagaimana mestinya karena sedikit dari rambutnya terlihat. Dalam aksi protes tersebut, perempuan di Iran membakar jilbabnya dan memotong rambut sebagai ekspresi kebebasan. Sambil menari dan berteriak “azaadi”, yang artinya kebebasan, perempuan di Iran menuntut penghapusan hukum wajib jilbab dan keberadaan polisi moral. Lambat laun, gerakan ini makin meluas ke berbagai daerah. Hingga pekan ketiga, sebanyak 92 orang meninggal dunia dalam gelombang aksi protes tersebut.

Teologi Kristen Barat yang eurosentris dan sangat tekstual ternyata kurang sesuai dengan konteks beragama di Indonesia. Gereja pun mengupayakan reinterpretasi terhadap teologinya melalui kontekstualisasi. Namun, seberapa inklusifkah teologi kontekstual?

Pola ketimpangan dan kesenjangan kekuatan antara kelompok dominan dan marginal tecermin dari bagaimana media membingkai berita. Salah satunya tentang berita persekusi Ahmadiyah di media siber lokal.

Peran media tidak sekadar mengamplifikasi pesan atau konten keagamaan, tetapi juga merekonstruksi agama di ruang publik.

Dunia hari ini membutuhkan mitos-mitos yang membantu kita mengenali sesama ciptaan dan bukan hanya manusia. Melalui mitos, pengenalan tersebut melampaui pragmatisme ekonomi yang melihat ciptaan lain hanya sejauh komoditas produktif dan menguntungkan bagi kepentingan manusia.

Laiknya hitam dan putih, agama dan kejahatan kerap dipahami sebagai elemen yang bertolak belakang. Padahal, tidak sedikit kejahatan terjadi atas nama agama.

Perdebatan mengenai mitos kerap terjebak pada pertanyaan apakah ia mengandung kebenaran atau kerancuan. Padahal, mitos dan sains adalah dua entitas berbeda yang memiliki cara kerja dan fungsinya masing-masing.

Pohon kerap menjadi simbol yang mampu mencairkan dan menjembatani relasi antaragama.Tak jarang, simbol pohon yang sama digunakan bersama oleh beberapa agama. Salah satunya Batang Garing. Pohon kehidupan masyarakat Dayak Ngaju di Kalimantan Tengah ini tidak hanya dapat ditemui di balai Kaharingan tetapi juga bertengger di puncak masjid dan menjadi ornamen sakral di altar gereja.

Kemunculan diskursus indigenous religion atau ‘agama leluhur’ dalam studi agama dan antropologi tak lepas dari kesadaran untuk melepaskan berbagai asumsi peyorasi—seperti animisme dan primitif—pada tradisi dan praktik masyarakat adat. Akan tetapi, penggunaan “indigenous” untuk merepresentasikan tradisi dan praktik adat ini juga tidak absen dari masalah.

“Honor killing” merupakan praktik yang mengakar pada banyak tradisi di dunia. Akan tetapi, isu kesetaraan gender dan perlindungan perempuan yang datang bersama dengan modernitas mengusik keberadaan tradisi tersebut. Salah satunya melalui CEDAW.

Meski mengundang kontroversi dan diskriminasi, masyarakat Hindu di India mempertahankan keberadaan kasta atas nama agama. Di sisi lain, konsep kasta yang nonegaliter tampak bertentangan dengan doktrin ajaran Hindu vasudaiva katumbhakam 'seisi bumi adalah saudara'. Lalu dari mana muasal kepercayaan kasta yang hierarkis itu?

The Marapu people who have been deprived from their lands have to deal with a coalition of corporations, the government, and the people who support the sugar plantation project. The Marapu people's religious worldview of land is being clashed with the perspective of a secularized society, which sees land to the extent that it provides financial benefits.

Monoteisme sering dianggap sebagai puncak dari pengalaman keagamaan manusia. Tak heran, dalam studi antropologi agama, monoteisme sering disandingkan dengan gerak evolusi peradaban manusia. Karenanya, keberadaaan temuan monoteisme pada masyarakat purba menjadi antitesis dalam teori evolusi agama. Akan tetapi, ada yang alpa dalam hiruk-pikuk perdebatan tersebut.

Sejak dua dekade terakhir, perjuangan dan pertarungan umat Baha'i melawan stigma kian tampak: mulai dari upaya mendapatkan hak-hak administrasi yang memadai hingga menegaskan eksistensi mereka sebagai agama independen, bukan aliran sempalan dari agama tertentu.

Tersebarnya agama-agama besar dunia dan terkucilnya agama-agama lokal bukanlah perkara agama lokal itu primitif sehingga perlu berevolusi menjadi agama modern atau monoteisme.

Masyarakat Marapu yang telah dicerabut hubungannya dengan tanah mereka harus berhadapan dengan koalisi korporasi dan pemerintah sekaligus masyarakat yang mendukung proyek perkebunan tersebut. Pandangan dunia religius masyarakat Marapu tentang tanah dibenturkan dengan perspektif masyarakat yang sudah tersekularisasi, yang melihat tanah sejauh itu memberikan keuntungan finansial.

Menurut Eliade, agama tidak bisa direduksi sebagai fenomena sampingan semata, yang mengandaikan agama sebagai variabel yang dependen atau akibat dari struktur sosial tertentu. Baginya, agama merupakan sesuatu yang 'sui generis': ia memiliki aspek-aspek esensial yang otonom, dan karena itu harus didekati dengan fenomenologi.

Bila melihat bahwa tujuan dari dialog antaragama bukan saja menyangkut isu teologis melainkan juga pemecahan masalah bersama terkait isu sosial, ekonomi, politik dan isu ekologis, eksklusi terhadap agama lokal dalam dialog antaragama berarti pengabaian terhadap mitra dialog yang amat berharga.

Durkheim berpendapat bahwa cara terbaik untuk memahami agama bukanlah melalui individu, melainkan melalui masyarakat, karena masyarakatlah yang membentuk individu. Sejalan dengan Marx dan Weber, Durkheim menempatkan agama pertama-tama bukan sebagai gejala psikologis individu, melainkan sebagai kenyataan sosial di masyarakat.

Bagaimana mestinya kita memposisikan beragam argumentasi keagamaan dan non-keagamaan dalam sistem demokrasi? Sejumah teoritisi demokrasi menawarkan adanya konsensus (rasional) berdasarkan penalaran publik. Namun, seberapa inklusifkah konsensus ini?

Istilah “paganisme” umum digunakan untuk merujuk pada praktik dan tradisi para penyembah berhala. Dalam sejarah, istilah ini lazim digunakan oleh komunitas Kristen awal di Romawi pada abad ke-4 guna membedakan keimanan mereka dari praktik dan tradisi para pemuja dewa. Namun, benarkah pemaknaan ini?

Sebelum gerakan ekologi modern diteorisasi, komunitas-komunitas adat atau agama lokal di pelbagai penjuru dunia merupakan kelompok yang menerjemahkan kesadaran ekologis dalam kehidupan sehari-hari dan berbasis pada kepercayaan religius yang melekat erat dalam kepercayaan mereka serta mendorong lahirnya aksi perlawanan terhadap para perusak alam. Salah satunya ialah gerakan Chipko di Uttar Pradesh, India.

Fransiscus van Lith mengupayakan akulturasi Katolik dengan budaya Jawa, memisahkan misi Katolik dari kepentingan kolonial, dan mendirikan sekolah yang melahirkan tokoh-tokoh Katolik pro-nasionalis, seperti Soegijapranata, yang terkenal dengan jargonnya "100 persen Katolik, 100 persen Indonesia".

Seturut pola yang terjadi di banyak wilayah lain di Nusantara, sejarah perubahan agama di Batak juga merupakan sejarah penyebaran agama dunia yang ditopang oleh kekuasaan dengan kepentingan ‘memperadabkan masyarakat yang primitif’.

Bagi orang Aceh dulu, adat dan agama bukanlah dua entitas dengan garis pemisah yang tegas. Adat bagi orang Aceh merupakan tata hidup masyarakat yang mencakup aturan agama, pembagian kekuasaan pemerintahan, perpajakan, distribusi ekonomi dan pertahanan. Pengertian ini berganti makna setelah Snouck Hurgronje mengubahnya.

Tentang gerakan Kristen Kang Mardika yang didirikan Kiai Sadrach: kemerdekaan untuk mengekspresikan Kekristenan berdasarkan pengalaman lokal orang Jawa dan kemerdekaan dari subordinasi oleh kaum kolonial.

Pembatasan terhadap kebebasan menjalankan agama dalam rangka menghadapi pandemi global COVID-19 dapat dijustifikasi oleh hukum HAM internasional. Namun secara prinsip, pembatasan ini tidak boleh menjadi alat untuk melakukan diskriminasi.

Perempuan rentan mengalami lebih banyak macam persekusi dibanding lelaki ketika menghadapi tindakan intoleransi. Namun, perempuan Ahmadiyah bisa memberdayakan diri untuk sadar dan memperjuangkan hak-hak mereka yang terdiskriminasi.

Ketegangan antara perlindungan keamanan nasional dan pemenuhan HAM dalam kasus eks-ISIS memang bukan hal yang mudah untuk dijembatani. Tetapi, benarkah tidak ada opsi-opsi untuk mengakomodasi keduanya?

Biasanya rekonsiliasi di Ambon menonjolkan ranah formalnya. Film "Beta Mau Jumpa" menyoroti ranah-ranah informalnya di akar rumput, di ranah lingkungan sekitar, di ranah fungsional, dan di ranah narasi.

With the loss of indigenous religions and language, there is loss of life. With loss of biological life comes loss of indigenous religions and languages.

Di kampung Ilawe, Alor, NTT, Muslim ikut membangun gereja, dan Kristen ikut membangun masjid. Hari besar keagamaan dirayakan bersama. Pernikahan beda agama biasa terjadi.

Dikotomi santri-abangan, juga istilah seperti ‘agama Jawa’ atau ‘Islam Jawa’, merupakan terusan dari konstruksi antropologis era kolonial. Penggunaan istilah ini mesti dibarengi dengan catatan kritis.

Pasca-Putusan MK 2017, regulasi pernikahan penghayat masih menyisakan masalah di tataran teknis administratif dan di tataran norma hukum, yang problemnya bisa ditarik hingga ke UU Perkawinan 1974.

Pidato pembuka Robert Hefner di International Conference on Indigenous Religions pada 1 Juli 2019 di UGM.

Liputan konferensi internasional tentang agama lokal di University Club UGM, 1 July 2019.

Ahmad Najib Burhani’s piece in The Jakarta Post (May 9) on the Ma’ruf Amin factor in Joko Widodo’s reelection success made two points worth reexamining.

UBN membingkai kontestasi pilpres 2019 dalam narasi perang: Quick Count dianggapnya 'sihir' dan ajang pemilu sebagi perang antara haq dan batil, antara tentara Thalut dan pasukan Jalut.

Respons terhadap terorisme di Sri Lanka tidak bisa dituntut sama dengan respons terhadap terorisme di Selandia Baru. Namun demikian, sudah semestinya kita mendukung gerakan solidaritas lintas iman Sri Lanka.

Manifesto pelaku teror di Christchurch, yang berjudul "The Great Replacement", berpandangan bahwa gelombang imigrasi dan tingginya angka kelahiran Muslim mengancam eksitensi ras kulit putih.

A review of Nahdlatul Ulama's call for an end to addressing non-Muslims as "kafir", an appeal arising from its recent national conference in West Java.

The attempt to understand the Islamists’ reasoning of Pancasila is important. Yet one should ask, what were the conditions that enabled and constrained such reasoning?

Rizieq Shihab, who condemned the New Order regime, has called the Soeharto's children-led Berkarya Party a "nationalist, Pancasilaist" party.

Yang tidak bisa diraih semuanya, jangan tinggalkan semuanya.

Six month after his appointment, Ma'ruf Amin appears to confirm the inclusion-moderation theory. But a closer look suggests it has yet to be the case.

Jika aplikasi Smart Pakem, sebagai upaya Bakor Pakem mengawasi aliran "sesat", dilanjutkan, maka amat mungkin kita justru akan menyaksikan lebih banyak kasus persekusi dan konflik alih-alih menciptakan kerukunan.

Catatan dari diskusi temuan survei nasional opini publik Lembaga Survei Indonesia di Perpustakaan Pusat, Universitas Gadjah Mada, 26 September 2018.

Review film "Our Land is the Sea", film tentang tiga generasi keluarga Bajau, di harian Kompas.

Demokrasi tak bisa bebas dari politik identitas. Maka yang diperlukan adalah penegakan mekanisme yang memastikan bahwa praktik politik identitas dilakukan secara beradab.

Tolerance, i.e. real and sincere tolerance, is not cheap. It costs; it has a price that we must pay if we really intend to be tolerant.

Catatan dari pengalaman personal, tentang Nazisme, anti-Semitisme, dan sekilas sejarah Yahudi di Indonesia.

"Terrorism is born out of an identity crisis as a result of a complex situation that has made the terrorists unable to behave like normal people."

What kind of parents could strap bombs onto their children’s bodies and lead them to commit suicide together? What kind of logic implanted in their minds?

A newly UN-recognized international day, proposed by Algeria, initiated by the International Association of the Sufi Alawiyya.

In insisting that “animist” faiths be given a lower status than “religion”, Islamic leaders ignore how the false divide between them was constructed in the first place.

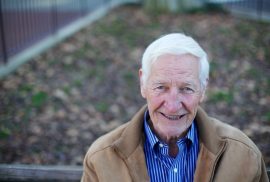

In memoriam John Raines, an inspiring professor, a pastor, an activist, who invaluably contributed to the founding of CRCS and taught the first generations of its students.

Bagaimana memaknai Reformasi Protestan dalam konteks kepelbagaian agama di zaman kiwari?

NU mengalami pergulatan yang dinamis dengan Pancasila. Di awal perumusan Pancasila, NU menginginkan Islam sebagai dasar negara. Sikap ini berubah seiring perubahan rezim dan konfigurasi politik.

A reflection by Kelli Swazey from the Seren Taun event in West Java, on how for indigenous communities religion and culture are in an intertwined relation.

Tentang macam-macam kelompok Muslim di Myanmar, isu kewarganegaraan, konflik etnoreligius, dan munculnya gerakan ekstrem yang makin menajamkan perseteruan Buddhis-Muslim. Bacaan pengantar dari Prof. Imtiyaz Yusuf.

Bagaimana hubungan agama dan kekerasan dalam tragedi Rohingya? Refleksi mahasiswa dari matakuliah Religion, Violence and Peacebuiliding di CRCS.

Setelah kasus "penodaan agama" mantan gubernur Jakarta, persekusi banyak terjadi di daerah. Tulisan ini membahas kasus dokter Otto Rajasa di Balikpapan.

Refleksi dari pertemuan lintas agama dan masyarakat adat untuk pelestarian hutan hujan dalam acara Interfaith Rainforest Initiative (IRI) di Oslo, Norwegia, pada Juni 2017.

"Pelaksanaan syariat Islam" mendapat payung dari undang-undang, yang memanifes dalam qanun-qanun, dan telah menjadi wacana hegemonik di Aceh. Bagaimana advokasi toleransi beragama dapat dilakukan dalam konteks demikian?

Berbagai kebijakan mengenai masyarakat, sejak masa kolonial hingga kini, telah kerap berubah. Namun pertanyaan utamanya tetap sama: sudahkah masyarakat adat berdaulat?

After being dissolved, members of Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia have choices to be ideologically consistent or to make compromise. Each has its own consequences.

Denni H.R. Pinontoan | CRCS | Perspective

The fraught election of a new leader for Jakarta has triggered reactions from regions across Indonesia and influenced the dynamics of local identity politics. As will be discussed in this essay, adat organizations promoting local identity as grounded in ethnic customs, in Minahasa, a Christian majority region of North Sulawesi, have gained momentum from controversies in Jakarta to reassert their existence by protesting against organizations they identify as intolerant towards Indonesian pluralism. Specifically, they have turned their attention to those groups pushing the position that, as a Christian, former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaha Purnama (known as Ahok), was not permitted (according to one reading of the Quran) to serve as the governor of a majority Muslim province.

However, we shouldn’t rush to characterize the reactions of these organizations based in adat and (Christian) religion as primordial or sectarian. There is a wider context that must be understood in the examination of these symptoms. The presence of these adat organizations and their self-declarations in the process of rejecting intolerance and political turmoil must also be read as an expression of politicized identities in the context of the dynamics of local politics.

Minahasan Identity in the Era of National Political Transition from the New Order to Reformasi and Democracy

Studies of the local politics in Indonesia which unfolded in a relatively new context during the transitional period from 1998 through the early 2000s have shown that local conflicts over religion and adat were not divorced from turbulent national politics. The conflicts in Ambon and Poso starting in 1998 through the early 2000s, and the efforts of “Islamic politics” groups in Jakarta lobbying for their political agenda in the national parliament provided the context through which regional/local communities understood their position within the so-called Unified State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI).

In Minahasa, various responses emerged to the threat of Islamicized politics. For example, a discourse of “Independent Minahasa” was heard at the first two Great Minahasa Congresses (Kongres Minahasa Raya). The implications of these statements should not be exaggerated as they were seen as reactionary and failed to find a wide reception with the Minahasan public. Instead, a discussion of federalism emerged, in connection with its well known supporter, Dr. Bert Supit, drawing on the ideas of national hero of the movement for independence from the Dutch Dr. G.S.S.J Sam Ratulangi. The idea of Minahasa as a unified political entity taking the form of a special autonomous province was also part of the conversation. These discourses originally only circulated amongst intellectual and political elites, and even they did not agree among themselves.

The early emergence of this discourse in the early 2000s therefore cannot be said to have had any significant impact. The point, however, is that the disconnected symbols of adat and culture used to represent Minahasan identity were drawn into political contestation for the first time since the Permesta conflict (1957-1962), when several generals from Minahasa sought to consolidate the regional public to challenge the central government in Jakarta.

Adat Organizations and Local Politics in Minahasa

The first adat organization to play a role in post-New Order local politics in Minahasa or North Sulawesi was the Manguni Brigade (Brigade Manguni or BM), formed in the year 2000 as response to violent conflicts in two regions not far from North Sulawesi: Ambon and Poso. The organization’s founders declared that it was created to protect the adat lands of Minahasa from the threat of conflict. Throughout its growth, BM consistently claimed to be organization dedicated to protecting the stability of Minahasa within the framework of “Indonesian-ness“. Yet the Manguni Brigade also reminded the Minahasan public of the period of Permesta, as its name and symbol (an indigenous owl (Otus manadensis) that is sacred in local tradition) were taken from one of Permesta’s military units.

Another notable organization is the Waraney (Warrior) Militia (Milisi Waraney or MW), a group with a more robust Christian identity. The orientation of the Waraney Militia is clearly portrayed in its logo depicting a yellow manguni owl with a blue Star of David in the background and a red cross above its head. The phrase “I Yayat U Santi” (loosely meaning “lift up and point your sword“) is written in color at its feet. This logo signals that, for the Waraney Militia, Minahasan identity references relations of (ethnic) descent and (Christian) religion. The Manguni Brigade uses the same image of the manguni owl and the slogan “I Yayat U Santi“.

In Minahasan tradition, the manguni is a sacred bird and “I Yayat U Santi” is commonly understood as the battle cry of the waraney (warrior).

Other civil society organizations that emerged in the early post-New Order years are the Christi Militia (unofficially affiliated with the Evangelical Church of Minahasa or GMIM), and the Legium Christum, associated with the Roman Catholic Church in the region. A number of other organizations with relatively similar aims were also formed in the late 2000s, well after violence in Ambon and Poso had ended. Their logos do not differ much from the one used by the Manguni Brigade, a blend of symbols for Minahasan local culture and Christianity.

In connecting these phenomena, it is increasingly clear that these organizations have responded on the basis of (Christian) religion. Since Christianity is perceived of as inseparable from local culture, the two identities are fused.

In 2014, these organizations found their platform when they united in response to the proposed renovation of the Al Khairiyah Mosque, one of the larger mosques located in the former Texas Village in the center of Manado, the capital city of the province. The organizations consolidated in an alliance they called the Alliance of the Kawanua Community for Tolerance (Makapetor). With this development, it was clear that the polarization of Christianity and Islam that began in the early post-New Order years had become the main context motivating the political actions of these organizations.

There are, in fact, many local Minahasan organizations based on adat and religion and many of these adat organizations have a different stance. the Mawale Cultural Center (MCC) is a network of cultural groups and Minahasan intellectuals that takes a critical position towards state intervention in cultural revival efforts in Minahasa. They express the same view towards adat activism by churches and towards the Christian identity that serves as a dominant force in local politics.

Leaders of such groups in the MCC network as the arts and culture organizations Waraney Wuaya and Pinaesaan Tontemboan (PITON) took a different perspective on the mosque renovation in Texas Village from those organizations based in a Christian identity. Although these two organizations were repeatedly invited to join the Makapetor Alliance, they remained loyal to MCC’s idealism that all people whatever their background have a right to live in Minahasa, as long as they honor the obligation to protect Minahasa as safe place to live together.

After the Jakarta Election, What Then?

The actions of Islamic groups to influence the Jakarta election, particularly the 411 and 212 “demonstrations to defend Islam,” infuriated many Christians in Minahasa. This gave Minahasan adat organizations the momentum to express their views.

In November 2016, several adat organizations in Minahasa organized an event calling for the disbanding of the Islamic Defender’s Front (FPI) regional branch in North Sulawesi’s provincial capital city of Manado. The main reason given for their demand was that FPI is a radical organization that threatens Indonesia’s diversity. They also emphasized that the national ideology of Pancasila, the founding laws of 1945, the national motto of Unity in Diversity and the concept of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI) are incontestable principles. The support of North Sulawesi’s Regional Leadership Coordination Forum (Forkopidma) for the participation of the adat organizations in the Unified Nusantara Parade scheduled for December 1st, 2016, gave the impression of the state’s recognition of the existence of these groups. On the other hand, perhaps they were not aware that recognition is also part of the state’s effort to maintain control.

Going along with the state’s doctrine and methods of ensuring stability through supporting the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia campaign appears to be a way for these Christian-adat organizations to negotiate the politics of Minahasan-ness and religiousness (identity politics) through the politics of the state in the local sphere. The actions of Islamic groups in Jakarta served as real and factual proof for their belief that “Islamic politics” poses a serious threat to the existence of Minahasan identity and Christianity.

Previous events, such as the appearance of local shariah-based policies in several other regions including in South Sulawesi, as well as the forced closure of a number of churches in Java, have successfully been reconstructed by elite members of these organizations to assure their members (primarily young people) that their participation is part of a noble struggle for the continued existence of Minahasa and freedom of religion as Christians.

In my view, it is this vision of “noble struggle” that will ensure the continued existence of these organizations in local politics in Minahasa. Yet I predict that these organizations will never become a unified group. The case of the Manguni Brigade can serve as a precedent. Around ten years after its creation, the group split, with an offshoot organization arising called Laskar Manguni Indonesia. Shortly afterward another offshoot emerged called Laskar Adat Manguni Indonesia (LAMI). Other organizations are experiencing the same fate, not primarily due to matters of leadership, but because the basis of their struggle is repeatedly reassessed as generations, political contexts, and interests change. Even the Makapetor Alliance is prone to division as it basically a short-term partnership between independent groups.

Focusing more on study, revitalization and discussion, MCC and its network have to some degree served as a stabilizing force in the discourse of local politics in Minahasa. During the response to the Jakarta election in the region, MCC intellectuals and activists, along with their wide networks across Minahasa, were more involved in peace activism with interfaith groups and other civil communities and were always cautious not to get cornered into campaigns for nationalism.

These events display the active dynamics of local politics in Minahasa. The adat organizations themselves are prone to dissolution because there is no single unifying ideology among them, and there is always space for differing opinions. This means that these groups inhabit a dialectical position in Minahasan local politics. Although they often give the impression of being ‘frightening’ or ‘extreme’ due to their militia or paramilitary character, these political dynamics will continue to prevent them from becoming more involved in physical violence towards the groups they identify as their enemies. In fact, these groups are still open to discussions about diversity with Muslim organizations like the Nahdlatul Ulama Paramilitary (Banser NU).

In addition to local dynamics, national political unrest also influences the movements undertaken by these adat organizations. The response towards the events surrounding the Jakarta election that spurred the consolidation the Christian adat organizations is one effect of these politics of the center that have spread to the outer regions.

Denni H.R. Pinontoan, a lecturer in Religious Studies in the Faculty of Theology at the Indonesian Christian University of Tomohon (UKIT) in North Sulawesi, is an alumnus of the School of Diversity Management IV held by CRCS in 2014.

This article is a translation by Kelli Swazey from its original version in Indonesian:Pilkada Jakarta dan Ormas Adat dalam Politik Lokal Minahasa.

Setelah dibubarkan, anggota Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia memiliki dua pilihan: tetap bersikukuh dengan prinsip ideologinya atau berkompromi dengan realitas politik. Masing-masing punya konsekuensi.

The overly optimistic view regarding the prospects for Indonesia's religious democracy needs to be qualified.

Konservatisme tak perlu menjadi sumber kecemasan. Isu yang lebih penting bersifat sangat praktis: bagaimana negara, khususnya aparat penegak hukum, mampu menjaga ruang deliberasi yang aman.

A “Pancasila Reinterpreted” project is needed to answer an important question: Can Pancasila be more inclusive toward human rights and religious freedom?

In memoriam for Taliesin Myrddin Namkai-Meche, a graduate of Reed College in Portland, Oregon, who was attacked on a commuter train in Portland on May 26th, 2017.

Sebagai salah satu pusat iman Kekristenan, Kenaikan Yesus selaiknya menjadi momen refleksi. Salah satunya tentang pesan Yesus sebelum naik meninggalkan para murid-Nya.

CRCS lecturer Greg Vanderbilt shares his reflections while visiting Christians in Indonesian peripheries observing their religious commemorations.

Pilkada Jakarta berimbas pada dinamika politik lokal berbasis identitas dari ormas-ormas adat-Kristen di Tanah Minahasa.

Yulianti | CRCS | Perspektif

Perayaan Waisak adalah salah satu hari besar umat Buddha untuk memperingati tiga peristiwa: hari lahir Sidharta Gotama (calon Buddha Gautama), momen Sidharta mendapatkan pencerahan ilmu, dan hari mangkatnya Buddha. Ketiga peristiwa ini terjadi pada bulan Waisak saat purnama.

Waisak dirayakan dalam berbagai bentuk dengan skala yang beragam. Denyut perayaan Waisak tidak hanya terasa di negara-negara berpenduduk mayoritas Buddha seperti Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, atau wilayah mainland Asia Tenggara lain. Negara-negara di mana agama Buddha tidak dipeluk mayoritas penduduknya seperti Indonesia pun menggemakan Waisak melalui acara-acara besar.

Sebagian dampak Pilkada DKI tak berhenti setelah pilkada usai. Meski berjalan sukses tanpa gugatan kecurangan, dan hasilnya diterima semua pihak, sulit merayakan keberhasilan itu dengan suka cita. Ia memang demokrasi, tapi dengan kualitas rendah, yang meninggalkan luka-luka serius.

Last week Ian Wilson wrote in a New Mandala article—subsequently republished at the Jakarta Post and a number of other English Language publications, as well as being translated into Bahasa Indonesia by Tirto—about issues of inequality and poverty that didn’t feature prominently in discourses surrounding Jakarta’s gubernatorial election, either in local or international mainstream media.

The critical content of Wilson’s article was largely aimed at the campaigns of both sides in the second round of the election. I agree with the main goal of the article, namely to oppose the dominant narratives in the Jakarta election, which have been framed in binary terms (‘diversity vs. sectarian populism’), and express the issues of inequality and poverty that are of paramount importance and therefore ought to be a priority of political programs. But my agreement is accompanied by two corrections and one additional note.

Allow me to quote one sentence that summarises the article’s content and forms its main thesis. Wilson says:

Jonathan D Smith | CRCS | Essay

Indonesia is home to many environmental movements, either led by established environmental activists or by groups of indigenous people. The reclamation project in Benoa Bay, cement mining in Kendeng area, Central Java, and the Save Aru movement are just a few recent examples. Does religion play a role in these movements? Are these local movements related to the growing global environmental movement?

The local and global is a crucial element of environmental movements, because environmental problems defy boundaries. Our rapidly-changing climate poses an urgent challenge that is both global and local. As national governments slowly acknowledge their role in reducing carbon emissions (with some exceptions), local communities in Indonesia are living with the problems of rising temperatures and sea levels, increases in natural disasters, and increasing pollution of our air and water.

Local-global connections in religious environmental movements

In 2016 at the climate summit in Morocco, governments met to affirm their adoption of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Signed by 111 countries (as of November 2016), the agreement commits to reducing carbon emissions and recognizes the human impact on climate change. At the same climate summit in Marrakech, hundreds of religious leaders and environmental activists launched the Interfaith Climate Statement.

The Interfaith Climate Statement included these words:

Laine Berman | CRCS | Voices from America

The United States and Indonesia are both plural societies that struggle to understand how to live together in diversity and with the meaning of pluralism itself. From its beginnings seventeen years ago, CRCS has had strong ties with American academia. Pioneers in inter-religious studies from the U.S., including John Raines, Mahmud Ayoub and Paul Knitter, were present at our founding and have been followed by a number of visiting lecturers who have stayed for a few weeks, months, or years, and by generations of English teachers. In addition, more than thirty CRCS alumni/ae have continued their studies for MA and PhD degrees in American universities. As we followed the news of the U.S. election within the context of the anti-pluralist turns across Asia and Europe, we wanted to know what our American friends are thinking and so we invited them to contribute their reflections to this page. This article, written by Laine Berman, is the second of the Voices from America series. To read the Indonesian translation of this article, click here. To read the first of the series, click here.

Kate Wright | CRCS | Voices from America

The United States and Indonesia are both plural societies that struggle to understand how to live together in diversity and with the meaning of pluralism itself. From its beginnings seventeen years ago, CRCS has had strong ties with American academia. Pioneers in inter-religious studies from the U.S., including John Raines, Mahmud Ayoub and Paul Knitter, were present at our founding and have been followed by a number of visiting lecturers who have stayed for a few weeks, months, or years, and by generations of English teachers. In addition, more than thirty CRCS alumni/ae have continued their studies for MA and PhD degrees in American universities. As we followed the news of the U.S. election within the context of the anti-pluralist turns across Asia and Europe, we wanted to know what our American friends are thinking and so we invited them to contribute their reflections to this page. This is the first of the Voices from America series. To read the Indonesian translation of this article, click here. To read the second of the series, click here.

Setelah Kunjungan Raja Saudi: Melawan Ekstremisme?

Azis Anwar Fachrudin – 7 Maret 2017

Di mata banyak orang, kunjungan Raja Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud boleh jadi menampakkan gestur yang positif. Namun satu hal yang tetap tak boleh terlupa ialah bahwa beberapa janji menunggu untuk segera dipenuhi. Satu pernyataan juga penting mendapat respons serius.

Setidaknya dua janji layak disebut di sini. Pertama, kompensasi terhadap korban cedera (42 orang) dan kelurga korban yang meninggal (12 orang) dari jamaah haji Indonesia dalam tragedi jatuhnya derek (crane) di Masjidil Haram pada 2015. Kedua, jaminan perlindungan terhadap Tenaga Kerja Indonesia di Arab Saudi, khususnya yang bekerja di sektor informal, serta penyelesaian dialogis dua negara untuk kasus 25 WNI yang terjerat pidana dengan ancaman hukuman mati.

Suhadi | CRCS | Perspektif

Bertebarannya hoax, provokasi, dan ujaran kebencian berbasis agama akhir-akhir ini merupakan fenomena yang sangat memprihatinkan. Untuk mengatasi hal ini, dengan tujuan yang berjangka panjang, pendidikan adalah hal yang tak bisa diabaikan.

Menyoroti hal itu, pada pertengahan Januari 2017, Jokowi memanggil Menag, Mendikbud, dan Menristekdikti. Sebagaimana diberitakan kemudian, menurut keterangan Menteri Agama Lukman Hakim Saifuddin, Presiden Jokowi antara lain memberikan pesan tentang pentingnya pengembangan pendidikan karakter bangsa terutama melalui pendidikan agama. Dengan bahasa lugas, Presiden berharap tiga menteri tersebut memberikan perhatian pada pengembangan pendidikan agama yang tidak konfrontatif, tapi “promotif”, yakni pendidikan yang mempromosikan religiositas dan sekaligus menghargai kebinekaan.

Dua aspek dari bangsa Indonesia menjadi pertimbangan dari upaya itu: di satu sisi, masyarakat Indonesia adalah masyarakat yang religius, atau setidaknya memiliki identitas keagamaan yang kuat; dan di sisi lain Indonesia memiliki kemajemukan agama yang sangat tinggi baik antaragama maupun intraagama. Kuatnya identitas agama di Indonesia itu diperkuat oleh hasil survei Pew Research Institute 2015 yang menyebutkan 95% orang Indonesia menyatakan agama penting bagi kehidupan mereka.

Temuan Penelitian

Penelitian tentang peran agama dan/atau pendidikan agama di sekolah dan pembentukan karakter siswa telah banyak dilakukan. CRCS UGM sendiri setidaknya telah mempublikasikan dua buku hasil penelitian dalam bidang ini.

Pertama, penelitian dengan judul Politik Ruang Publik Sekolah: Negosiasi dan Resistensi di SMUN di Yogyakarta (Hairus Salim HS, dkk, 2011). Buku ini menyajikan etnografi tiga sekolah negeri, dari yang toleran, “biasa”, dan kurang toleran terhadap kemajemukan. Penelitian ini tidak secara khusus mengkaji pendidikan agama dalam ruang kelas, tetapi tentang proses pembentukan ruang publik sekolah dan pengaruhnya terhadap relasi antar siswa.

Kedua, penelitian dengan judul Politik Pendidikan Agama: Kurikulum 2013 dan Ruang Publik Sekolah (Suhadi, dkk, 2014). Terbitan penelitian ini membahas genealogi atau asal usul pendidikan agama dalam sistem pendidikan nasional di Indonesia serta aspek politik pendidikannya dari satu rezim ke rezim lain setelah Indonesia merdeka. Penelitian ini juga mengkaji persoalan “kompetensi spiritual” dalam Kurikulum 2013.

Penelitian lain tentang pendidikan agama terkini juga telah dilakukan oleh Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat (PPIM) UIN Syarif Hidayatullah yang fokus pada content analysis buku-buku teks ajar Pendidikan Agama Islam (PAI) dari SD sampai SMA yang diterbitkan oleh Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan (Kemendikbud). Policy brief dari riset ini diterbitkan pada September 2016 dengan judul Tanggung Jawab Negara terhadap Pendidikan Agama Islam.

Latar dari penelitian tersebut adalah fenomena protes dari masyarakat di beberapa daerah yang menemukan pernyataan intoleransi dan kekerasan dalam buku-buku dan Lembar Kerja Siswa (LKS) PAI. Salah satu dari pernyataan itu, misalnya, dapat ditemukan dalam sebuah LKS PAI Kelas XI SMA di beberapa daerah sekaligus (Jombang, Depok, Jakarta, Bandung) yang memuat kalimat “yang boleh dan harus disembah hanyalah Allah SWT, dan orang yang menyembah selain Allah, telah menjadi musyrik dan boleh dibunuh.” Meskipun pernyataan itu tak mengacu secara khusus ke suatu agama, tim PPIM mengkhawatirkan pernyataan itu dalam konteks Indonesia dapat disalahpahami merujuk pada pemeluk agama tertentu di luar Islam (PPIM 2016:4)

Sebagaimana disebutkan dalam policy brief PPIM itu, setelah ditelusuri LKS tersebut ternyata menyalin secara utuh buku Pendidikan Agama Islam dan Budi Pekerti Kelas XI SMA yang dipublikasikan oleh Kemendikbud (Mustahdi dan Mustakim 2014; PPIM 2016: 4). Walhasil, sinyalemen bahwa ada potensi intoleransi dan kekerasan dalam buku teks PAI bukanlah mengada-mengada.

Ketika diwawancarai tim peneliti PPIM, pejabat Kemendikbud menyebutkan mengapa hal tersebut bisa terjadi. Menurutnya, proses penyusunan dan penerbitan buku-buku tersebut bersifat kejar tayang atau terpepet dari sisi waktu, sehingga hasilnya tidak maksimal. Namun peneliti PPIM memandang buku-buku PAI bisa dimasuki pernyataan seperti di atas karena pemerintah tidak memiliki visi menjadikan PAI sebagai bagian dari politik kebudayaan nasional atau bagian dari upaya memperkuat Islam rahmatan lil’alamin (PPIM 2016: 6).

Berpikir Lebih Mendasar

Banyak pihak telah lama menyarankan pemerintah secara serius memikirkan dan mengupayakan perbaikan PAI yang kontekstual dengan keindonesiaan dengan ragam agama, paham kegamaan, dan etniknya. Persoalan memperbaiki kurikulum PAI tidaklah semudah membalikkan tangan. Untuk hasil yang lebih maksimal ada perlu perubahan pola pikir dalam memandang pendidikan agama yang lebih mendasar.

Pertama, Pendidikan Agama (PA) secara umum, tidak terkecuali PAI, dalam sejarahnya memuat beban ideologis. Sebelum tahun 1966, Pendidikan Agama (PA) bukan mata pelajaran wajib, tetapi pilihan. Namun instruksi TAP MPRS No. XXVII/MPRS/1966 tentang Agama, Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan kemudian menetapkan PA sebagai mata pelajaran wajib bagi semua siswa. Pewajiban tersebut, pada waktu itu, berkaitan dan berhubungan dengan bias anti-komunisme. Artinya, ada aspek semangat penegasian sang liyan. Karena sentimen anti-komunisme ini dan agama yang diakui oleh perundang-undangan saat itu (masih berlaku hingga saat ini) hanya enam agama, maka pendidian agama di luar enam agama tersebut tidak pernah ditawarkan sepanjang sejarah.

Untuk konteks saat ini, hal yang penting adalah bagaimana menggeser paradigma tersebut ke arah yang lebih positif. Saya tidak sedang ingin mengusulkan kembali PA menjadi tidak wajib lagi, tetapi bagaimana keberadaannya yang wajib kini lebih memiliki semangat positif. PAI harus keluar dari perspektif negatif menuju perspektif yang lebih positif dalam melihat perbedaan agama dan paham. Tanpa perubahan paradigma yang mendasar, harapan terhadap PAI, bahkan juga pendidikan agama lain, untuk menjadi “promotif” dan tidak konfrontatif akan sulit tercapai.

Kedua, kurikulum terbaru yang berlaku saat ini, yakni Kurikulum 2013 (selanjutnya disingkat K-13), tidak lagi menjadikan Pendidikan Agama sebagai satu-satunya ruang untuk menanamkan nilai-nilai keagamaan/spiritualitas. K-13 memperkenalkan konsep Kompetensi Inti (KI) dan Kompetensi Dasar (KD). KI kemudian diturunkan ke dalam empat kompetensi: kompetensi spiritual (KI-1), kompetensi sosial (KI-2), kompetensi pengetahuan (KI-3) dan kompetensi keterampilan (KI-4). Oleh karena itu kompetensi agama/spiritual tidak lagi hanya menjadi tanggung-jawab PA, tapi semua mata pelajaran. Artinya, agenda perbaikan terhadap kurikulum dan buku teks PAI tidak niscaya menyelesaikan masalah yang diprihatinkan di atas. Maka kita sekaligus juga harus memeriksa rumusan KI-1 yang tersebar di semua mata pelajaran.

Ketiga, banyak di antara pemerhati dan praktisi pendidikan sering terjebak menyederhakan tujuan pendidikan dalam kaitannya dengan tanggung jawab mata pelajaran tertentu. Misalnya, ketika dalam UU No. 20 tahun 2003 tentang Sisdiknas disebutkan bahwa tujuan pendidikan adalah mendorong peserta didik agar menjadi “manusia yang beriman dan bertakwa kepada Tuhan Yang Maha Esa”, tujuan itu dianggap menjadi tanggung jawab mata pelajaran PA. Sementara itu tujuan pendidikan untuk mendorong “menjadi warga negara yang demokratis serta bertanggung jawab” seringkali dianggap menjadi beban Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan (PPKn). Paradigma semacam ini mengakibatkan adanya ambiguitas, yaitu PPKn mengajarkan keterbukaan sosial kebangsaan, sementara PA mengajarkan ketertutupan sosial kebangsaan.

Pemahaman ambigu tersebut seharusnya diakhiri. Mendorong lahirnya generasi bangsa yang “demokratis”, “bertanggung jawab”, “mandiri”, dan seterusnya, juga merupakan tanggung jawab pendidikan agama. Oleh karena itu, kurikulum PA seharusnya tidak saja berkutat pada keimanan dan ketakwaan, tapi juga hal-hal yang menyangkut sosial dan kebangsaan.

Perbaikan kurikulum terhadap buku teks yang konfrontatif memang menjadi agenda mendesak yang perlu segera dilakukan. Lebih dari itu, kita perlu memperbaiki hal-hal mendasar yang menyangkut paradigma dan pola pikir kita tentang pendidikan agama apabila mengharapkan pendidikan agama menjadi mata pelajaran yang lebih promotif terhadap nilai-nilai kebinekaan bangsa Indonesia.

*Penulis, Suhadi, adalah dosen Program Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga dan associate researcher di Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS), Sekolah Pascasarjana UGM.

Gregory Vanderbilt | CRCS UGM | Perspective

The kyai switched to English for just one sentence as he joined other village leaders in welcoming CRCS’s Eighth Diversity Management School or Sekolah Pengelolaan Keragaman (SPK) to the village of Mangundadi, 23 km west of Magelang, at the foot of Mt. Sumbing. Perhaps his choice was to honor the diversity present in this group—or that the chasm from ivory tower to mountain village had been bridged for an afternoon—as we tried to absorb the dance performance based on the carved reliefs of Borobudur we had just experienced. Though the village is 24km away from the 10th-century sacred site, and Muslim, it and its arts are part of the Ruwat-Rawat Festival movement that seeks to re-sacralize the great Buddhist monument from the disenchantment of the tourism industry and the weight of the busloads that climb it each day to snap selfies and admire in passing the craftsmanship of a millenium ago.

We were there because of the friendship with Ruwat-Rawat founder Pak Sucoro that has developed over the last year thanks to CRCS alumna Wilis Rengganiasih. Owner of the counter-narrative-producing Warung Info Jagad Cleguk across from the gates to the Borobudur parking lot and instigator of the eight-week festival each April-May, he had arranged an amazing afternoon for the excursion that has become an important change-of-page for SPK members after a week of ideas and passionate discussion. On the Saturday of the ten-day long school, the twenty-five members of SPK plus facilitators and friends departed by bus the school’s venue at the Disaster Oasis in Kaliurang, heading first to the warung at Borobudur to meet our guides and then heading another hour west from Magelang.

The road to the village of Mangundadi was too steep for our bus and so we were met at the main road by the pickups and motorcycles of the young men of the village. Having climbed on board, off we went to Mangundadi, the motorcycles revving their engines in a chorus of welcome. Afterwards SPK staffer Subandri admitted that he has now a tinge of positive feeling when he hears the youth gangs disrupt the city streets with their noisy machines, because what a welcome it was! When we reached the village, women lined the lane to shake our hands as we were ushered into one house to catch our breath, and then to process around the village’s new mosque with the genungan ritual mountain of vegetables, followed by the groups of performers, children, youth, adults, already in gorgeous costume and make-up. By the time we had feasted in another house, the performers were ready and, as the rain fell, they danced scenes from the stone reliefs. In the end, Pak Sucoro pulled some of us onto the stage to move with them and then they offered their salims and went back to their villages.

In the evening we returned to the Omah Semar retreat house near the monument-park for a discussion with Pak Sucoro about his vision of Borobudur as a universal spiritual heritage and as a place of spiritual significance for local culture, a place for Indonesian society to make a new choice, to live in harmony with God, nature, and each other. The Ruwat-Rawat has incorporated and re-ignited local traditions by focusing them on a global question, the question I asked the Advanced Study of Buddhism students who met Pak Sucoro back in May: who owns Borobudur? The next morning, walking across the lawns where his village once stood, we could see the stupa-monument in a new way.

In the evening we returned to the Omah Semar retreat house near the monument-park for a discussion with Pak Sucoro about his vision of Borobudur as a universal spiritual heritage and as a place of spiritual significance for local culture, a place for Indonesian society to make a new choice, to live in harmony with God, nature, and each other. The Ruwat-Rawat has incorporated and re-ignited local traditions by focusing them on a global question, the question I asked the Advanced Study of Buddhism students who met Pak Sucoro back in May: who owns Borobudur? The next morning, walking across the lawns where his village once stood, we could see the stupa-monument in a new way.

This was my third SPK since I came to CRCS in 2014. For me, it is an opportunity to meet the activists, academics, government workers, and media people who come to participate and see how change is happening across Indonesia. Each SPK may have its own character—this one, for example, was quicker to start singing than put on a mop of cringe-worthy joke telling—but the greater tone of excitement at being among others as serious of purpose and as ready to be challenged to greater intellectual depth is constant. The participants are excited by guest insights from Bob Hefner and Dewi Candraningrum but even more by the well-developed program from a core of facilitators devoted to teaching “civic pluralism” as a paradigm for just co-existence in the contexts of Indonesian diversity, one basing access in the three Re-‘s of recognition, representation, and redistribution, combined with thinking systematically about such core CRCS emphases as taking apart religion as lived and governed in Indonesia, digging into research for advocacy and putting into practice the theories and methods of conflict resolution. Equally important, they stay up late sharing their work, from teaching to preaching to activating NGOs to working conscientiously from inside government. Some know of the program because they have heard about CRCS while visiting or studying in Yogyakarta; others, following friends and co-workers who applied previously; and others still from searching online for “pluralism school” in order to serve better as religious and social leaders.

Visiting SPK alumni in their homeplaces—Jakarta, Aceh, West Sumatra, and Jambi, so far—has also shown me glimpses of grass-roots possibility across Indonesia. Trainings and workshops are regular features of Indonesian civil society, but it appears SPK leaves a more lasting impression on its participants. This is perhaps because of the intensity of their twelve days in the aptly named Disaster Oasis and perhaps because it challenges them more to take an intellectually grounded, hopeful framework to the places they are working and asks them to return with a research project, on how a pluralistically civil society is being made in soccer clubs and local studies movements and activism for gender (five from SPK-VIII work against domestic violence) and ethnic equality and film festivals and women’s economic literacy programs in villages and so on. In that way, the village kyai is right.

*The writer, Gregory Vanderbilt, is a lecturer at CRCS, teaching courses, among others, on religion and globalization; and advanced study of Christianity.

Aksi Super Damai 212 patut diapresiasi sebagai bukti kemajuan dan kedewasaan umat Islam Indonesia dalam mengekspresikan aspirasi politiknya. Kesejukan yang hadir dalam aksi ini sudah seharusnya diapresiasi.

Namun demikian, bagi peserta aksi, tujuan mereka bukan sekadar membuktikan bahwa Aksi Bela Islam adalah gerakan damai. Ratusan ribu atau bahkan lebih dari sejuta orang bersusah payah mendatangi Jakarta dalam aksi 212. Sebagian bahkan rela jalan kaki berhari-hari demi “membela Islam”, dengan tuntutan memenjarakan Ahok. Menariknya, meskipun Ahok tidak ditahan, para peserta aksi 212 tampak pulang dengan perasaan menang.

Sampai esai ini ditulis, perayaan kemenangan masih berlanjut. Linimasa masih dibanjiri konten dan unggahan yang menunjukkan kedahsyatan momen setengah hari di bawah Monas itu. Sebagian bahkan menawarkan cenderamata dan kaos untuk mengenang momen kemenangan.

Lantas pertanyaannya: apa yang sebenarnya telah dimenangkan?

Perang Posisi, Bukan Perang Manuver

Bagi banyak orang, partisipasi dalam aksi 212 bisa menjadi bagian dari momen langka yang tidak terlupakan. Berada di tengah lautan manusia untuk “membela Islam” merupakan kepuasan spiritual. Aksi yang begitu besar, yang dilakukan dengan tertib dan tanpa menyisakan sampah, adalah sebuah kemenangan dalam melawan wacana atau tuduhan tentang ancaman kekerasan dan makar.

Ashabul Fitnah dan Kehancuran Sebuah Bangsa, Pelajaran dari Suriah

M. Iqbal Ahnaf – 7 Maret 2016

Ketika baru-baru ini seorang ‘ustadz’ di laman facebooknya memosting gambar Imam Besar Universitas Al-Azhar sedang berciuman dengan Paus Fransiskus banyak orang langsung menuduh bahwa sang ustadz sedang menyebar fitnah. Setelah dilaporkan ke polisi atas tuduhan mencemarkan nama baik, sang ustadz tidak bisa mengelak; seakan mengakui telah menyebar foto palsu ia segera menghapus alat fitnah tersebut dari laman facebooknya. Tapi ironisnya ia tidak mengakui kesalahannya, tetapi justru menyampaikan bahwa ia memosting foto tersebut dengan ‘niat baik’ mengingatkan umat Islam agar menolak upaya berdamai dengan penganut Syiah sebagaimana pesan Sang Imam.

Tolikara, Idul Fitri 2015: Tentang Konflik Agama, Mayoritas-Minoritas dan Perjuangan Tanah Damai

Tim Penulis CRCS – 19 Juli 2015

Suasana Idul Fitri di Kabupaten Tolikara, Papua terusik dengan berita kerusuhan yang menyebabkan satu orang meninggal dan belasan terluka karena tembakan aparat; serta puluhan kios dan sebuah musholla di dekatnya dibakar (menurut satu versi, musholla bukan target utama tapi ikut terbakar). Sejauh ini telah muncul berita dari beberapa sumber, yang sebagian tampaknya masih perlu diverifikasi. Namun, sebagian lain, sayangnya, dalam keterbatasan informasi yang ada kini, sudah “menggoreng” berita itu untuk melakukan provokasi lebih jauh, hingga ke tingkat menggiring isu ini menjadi konflik kekerasan antara Kristen dan Muslim—bukan hanya di Tolikara, tapi Papua, bahkan jangkauannya diperluas hingga Indonesia, mungkin juga ada yang memperluasnya untuk berbicara mengenai Muslim-Kristen di dunia!